Making, Baking, and Laying Bricks

by Ed Crews

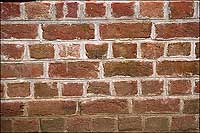

The alternating rows of bricks laid side by side and end to end denote English bond, one of two standard styles of bricklaying.

The second style, Flemish, set alternating long and short in the same row. One can find Flemish and English bond at Colonial Williamsburg.

The fall firing draws crowds to Colonial Williamsburg's brickyard kiln, where 15,000 bricks made throughout the spring, summer, and early autumn are hardened by the flames. A practiced eye for time and temperature is required to judge when they are done.

Stomping in the clay pit, a muddy delight for children and grownup Colonial Williamsburg guests, was the tedious but only way to mix clay for bricks in the age before machines.

Before they are fired, bricks are set out to dry in the sun, each turned by hand to ensure even drying, and carted and piled under covering until they are moved to the kiln.

THE BRICKYARD MAY BE the most kid-friendly site in Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area. At first glance, it looks rough and utilitarian and an unlikely attraction for youngsters. Big stacks of bricks and firewood rise beside piles of "bats," as broken bricks are called. There are mounds of oyster shells ready to be burned to make lime for mortar. Rows of sodden earthen blocks soldier across the barren drying yard. But children love the brickyard. They like laying out wet bricks and they like watching the kiln. Most of all, they like the huge mud hole—the treading pit. There, young guests, and older guests, too, take off their shoes, step into the slippery, gooey mire, and mix clay and water with their feet, preparing the raw material of bricks. The pit is a great place to get dirty, squeal with friends, and get a foots-on feel for history.

Colonial Williamsburg's masonry trades team—supervisor Christine Trowbridge, apprentice Jason Whitehead, and interpreter William Neff—runs the brickyard. It focuses on preserving eighteenth-century brickmaking and bricklaying, and teaching guests about the trades.

Brick was an important construction material in 1700s Williamsburg. Wood was plentiful and used frequently. But it was impermanent, subject to fire, rot, and termites. Stone was durable but scarce in the region. Brick was sturdy and attractive, and its raw material—clay—was abundant. Brickmaking and bricklaying were two of the Virginia colony's earliest trades. At nearby Jamestown, colonists were making bricks by 1610. Archaeologists have found kiln remains there dating to the 1630s.

Colonial brickmaking often was compared to farming because of its seasonality, and to baking because of its production methods.

Like farmers, brickmakers worked hardest in spring, summer, and fall. During winter, they might dig clay. But cold months typically were quiet. During good spring, summer, and autumn weather, they molded bricks and fired them. Like bakers, brickmakers mixed their main ingredient with water until it had a dough-like consistency. They rolled the clay in sand and packed it in a wooden mold. Some molds were rectangular, like modern bricks. But there were molds for coping bricks, half circles used to divert water; water-table bricks, used where the foundation and first floor met; square paving bricks; and compass bricks, which were roughly wedged-shaped and used to make circles. There was no standard or uniform size. Bricks needed only to fit easily in a brickmaker's hand.

Brickmakers took the wet brick from the mold and put it on the ground to dry. Laborers turned them periodically to ensure uniform drying. Once dry to the touch, bricks were moved to a shed until it was time to fire them. These steps are not particularly engaging or fun filled over an extended period, Neff said.

"Molding is not as tedious as treading, but they're both definitely what one could call dull. Fortunately, we switch from job to job frequently, and all the work is broken up with questions from the guests, so we're able to engage our brains at least a little while doing the mind-numbing labor of the brickyard. It's hard to imagine how it was for the eighteenth-century folks who had to do the same thing day in and day out for months each year."

The art of brickmaking lay in building and firing the kiln. Kilns were unfired bricks stacked oven-like with fire tunnels running through to distribute the heat. The fires burned constantly until the bricks hardened. The brickmaker watched the process closely, controlling the heat carefully. In the age before factory dials and gauges, this meant noticing the release of steam from the bricks and the changes in their color as they baked. Kilns could be large structures. Colonial Williamsburg typically fires 15,000 bricks every autumn—an annual ritual that attracts crowds.

"We've got to face it—people love fire," Neff said. "As far as I'm concerned, that is the primary reason people like to witness the kiln firing every October. It is an amazing process, and many folks seem to find it very interesting. It's quite different from everything else going on at Colonial Williamsburg, and we're open late into the evening during the firing."

A knowledgeable eighteenth-century brickmaker with a hardworking crew might make as many as 125,000 bricks annually. Although impressive in an age of hand production, this rate still would not meet the needs of the largest projects. Williamsburg's colonial Capitol, for instance, required about 600,000 bricks.

Eighteenth-century bricks were made at the construction site, so colonial brickmakers lived an itinerant life, moving from project to project. Thomas Jefferson, for example, hired brickmaker John Brewer to work on Monticello. Brewer lived there with his wife, drawing pay, food, and other necessities. Brewer, like others in his business, did not bring his own work crew. Clients provided workers. Almost anybody—men, women, and children—could assist because brickmaking was unskilled labor.

If brickmaking was for the untrained, bricklaying definitely was for the well trained. Learned through an apprenticeship, bricklaying required physical endurance, an eye for keeping a brick wall straight, an aesthetic sense, and a practical knowledge of construction techniques. Some bricklayers had great skill and became de-facto architects.

Bricklayers didn't produce bricks, but they did make the mortar, also at the construction site, from a mix primarily of lime and sand. By modern standards, colonial mortar was finicky. It dried slowly and couldn't be allowed to freeze in winter or to dry too quickly in summer. Bricklayers often put wet tarps over unfinished walls to allow optimal, even drying in hot weather. Despite its temperamental nature, eighteenth-century mortar proved durable once it hardened, a fact demonstrated by surviving walls, buildings, and foundations, some fourteen inches thick. Brick foundations were sturdy. Williamsburg's colonial building codes recognized that by requiring them for all homes built in town.

Colonial Williamsburg apprentice Whitehead has worked on bricklaying projects in the Historic Area, and developed in the process a respect for his colonial counterparts.

"The trick to successful bricklaying is keeping your work level and plumb," he said. "The main thing you have to focus on are the corners of a building. The drawings give you a building's dimensions. Then, you build the corners. You must have them meet at a perfect ninety-degree angle. As you go, you keep checking for level and plumb. You have tools to help—frames, levels, plumbs—but you must train your eyes to see what is straight without using tools."

As they built walls, bricklayers had to pay attention to the brick patterns, known as bonds, they used. Two bonds dominated—English and Flemish. The English bond had alternating rows of brick laid end-to-end and then side-to-side. Flemish Bond had short and long sides alternating in the same row.

Many bricklayers did plastering, too. Interior walls in colonial buildings, particularly homes, were covered in plaster. Its ingredients included lime, sand, and a binder like animal hair. Plaster went directly on bricks or wood. The smoothest appearance required carefully applied coats. Like mortar, plaster took a while to dry. Once it did, it could be painted, whitewashed, or covered with wallpaper.

When you talk with the masonry staff, you get a sense that learning the bricklayer's skill and teaching guests about them can be fun.

"I'm outside. I'm barefoot in the mud," Whitehead said with a grin. "Best of all, I like the tangible quality of this work. I can see 11,000 bricks I helped make. Or I can look at a wall I worked on and know that it will be seen by thousands of guests and last for decades."

Ed Crews contributed to the autumn 2005 journal an article on tailoring at Colonial Williamsburg.

For further reading:

- A History of Historic Trades in the Winter 2004-2005 Journal

- "With all the Grace of the Sex" in the Spring 2004 Journal