A History of Historic Trades

by James M. Gaynor

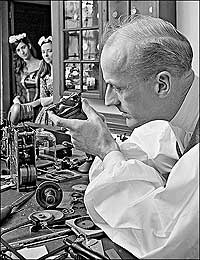

The

author, director of Historic Trades, surrounded by the results of his

colleagues' work, among them gunsmithing, wheelwrighting, millinery,

basketmaking, brickmaking, printing, cabinetmaking, coopering, saddlemaking,

wigmaking, tailoring, and shoemaking.

Get a closer look at some of the items in this image

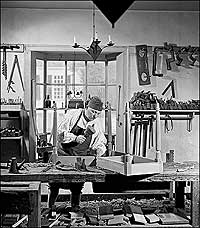

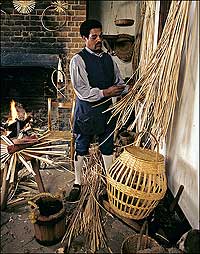

If you listen as you stroll the streets of Colonial Williamsburg, you hear the pulses of work. There is the whoosh of a sharp plane surfacing a board, and the rustle of silk as a gown is sewn. Axes thump into wood, and anvils ring to hammer strikes. Those sounds are the heartbeats of the Historic Trades program, a community of men and women at more than twenty sites, nearly one hundred masters, journeymen and journeywomen, apprentices, and interpreters practicing more than thirty eighteenth-century trades. Millinery and mantua, or gown, making. Tailoring, wigmaking, weaving, and dyeing. Shoemaking. Saddle- and harnessmaking. Cabinetmaking, carpentry, coopering, basketmaking, and wheelwrighting. Blacksmithing, silversmithing, gunsmithing, founding, printing, bookbinding, medicine, brickmaking. Foodways and rural trades.

Nowhere else in America or Europe can you go to learn so much about traditional, preindustrial trades except the streets of the Historic Area. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation researches and replicates eighteenth-century Anglo-American technology, perpetuating historic trades. Some survive only because of the foundation's long-term dedication to preserving ephemeral human skills. The tradespeople are professional, full-time artisans dedicated to specific occupations, practicing them publicly, sharing their knowledge with guests and participants in outreach programs.

Some of the best traditional artisans in the country work at Colonial Williamsburg, where many were trained, serving six- or seven-year apprenticeships to become journeymen or journeywomen. Combining their range of skills and the variety of products they can produce, the program re-creates a realistic model of eighteenth-century production systems. Colonial Williamsburg is the only institution around that can construct a carriage or build and furnish a house, from the ground up, using almost exclusively eighteenth-century type materials, tools, and skills.

From at least the early 1930s, the Williamsburg Restoration was thinking about a craft program, and in July 1936, the Restoration formed Williamsburg Craftsmen Incorporated, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Colonial Williamsburg. In October, President Kenneth Chorley announced the reestablishment of "authentic handcraft industries."

Chorley said that until then the institution had been mostly concerned with the restoration of the architectural features and their furnishings. During this time the Department of Research of the Restoration has been conducting an extensive study of the life and habits of the people of the period. This research has established the importance of the handcraft industries in Williamsburg during the eighteenth century and revealed the methods and customs of the craftsmen...It has been felt that the Restoration would not be complete without a revival of these crafts and that their re-establishment would add greatly to the interest of visitors if they might see how colonists in Virginia during the eighteenth century made many of the articles with which they lived.

The Restoration had received requests for reproductions, paints, and souvenirs. Commercial manufacturers would supply many of these, and they would be sold through the Craft House. But others were to be manufactured and sold in on-site shops. Williamsburg Craftsmen would lease shops in the Historic Area to contractors. Colonial Williamsburg would control the products and receive a percentage of sales.

In October 1937, the first shops opened. Boone Forge of North Carolina ran a blacksmith shop at the Deane Forge. Kittinger Furniture of Richmond, Virginia, presented a cabinet shop at the Ascough House. Max Reig made and sold pewter and jewelry at the Margaret Hunter Shop.

As early as 1938, there were concerns. Curator Jim Cogar believed the shops should look more like period shops, and efforts were made to furnish them authentically. Of greater import was a growing conflict between having merchandise that was as historically accurate as possible and merchandise that would make the shops economically viable. The shop operators wanted to sell nonauthentic items.

In 1939, the Restoration decided to put the shops under Cogar. They were to be furnished as "typical Craft Shops of the eighteenth century." Their function became the same as the exhibition buildings', and, although some work such as repairing antiques was to be conducted in them, no items were to be sold.

In April, spinning and weaving were introduced in the Wythe House south office. In September, candlemaking began at the Governor's Palace scullery. In 1940, the barber and peruke maker opened at Prentis Store, and the bootmaker began work at the Repiton Shop. The shops were to show the other side of everyday life and illustrate how it was done in the days of old.

Some attendants had worked at their shop's trade as it was practiced during the early twentieth century. They were to interpret from the standpoint of a professional hand artisan, and do some manufacturing and repairing. But the emphasis was on generic hand work, and in those shops where modern back-up facilities speeded the process—like the cabinet shop—there seemed to be no hesitation to use modern machinery and methods behind the scenes.

It is likely that if the Restoration had been asked about its philosophical approach to these shops, it would have said something along the lines of a brochure issued by the Vermont Guild of Old Time Crafts and Industries, an organization Colonial Williamsburg consulted as it established its program:

Probably the most important value of the project is the educational. There is no better way of education (as all progressive educators now admit) than a practice of the old crafts wherein there is that fine co-ordination of mind and hand. Further, there is the profound significance of the historical perspective where we of today may understand, through learning the crafts, something of the spirit which dominated our forefathers.The brochure abounds with such phrases as "preserving the best methods of honest hand work and skill" and "the ideals of the crafts spirit."

World War II hit Colonial Williamsburg hard, and during the spring of 1942, the Restoration closed the shops. Cabinetmaking continued behind the scenes, doing repairs and restorations. In 1946 and 1947, as shops began to reopen, it appears that the Restoration decided to redirect the effort. In 1948, the Craft Shop Program began, headed by Minor Wine Thomas, and in the Department of Interpretation. It was the beginning of the craft program of today.

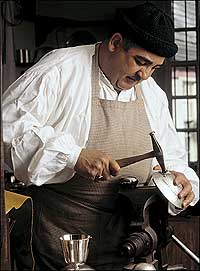

During the 1950s, it expanded. New sites and shops included the Printing Office and, a bit later, a bookbinder, the apothecary shop at the Pasteur-Galt site, the Raleigh Tavern bakery, the millinery shop, the silversmith at the Golden Ball, and the windmill. Interiors were authentic-looking spaces, and attendants interpreted the surroundings and the trade. But most shops again sold items across the counter.

A mimeographed handout issued during the 1958 Christmas season encouraged employees to do their holiday shopping at the craft shops. Among other goods, the apothecary offered candy, candles, spices, and tobacco; the windmill, flour and cornmeal; the bootshop, belts, handbags, fire buckets, and the leather jugs and drinking vessels called blackjacks. The silversmith sold jewelry and hollowware; the blacksmith, trivets, fireplace tools, and miniature horseshoes hand stamped with your name.

A 1950s report said the craft shops "again show machine-age Americans what great advances have been made in production. Nothing in Williamsburg more graphically illustrates the simplicity and yet the rigor of eighteenth-century life." But it was the 1950s, and Colonial Williamsburg had a larger mission. The Cold War was on. A visit to Williamsburg was to be a patriotic pilgrimage, and Williamsburg responded.

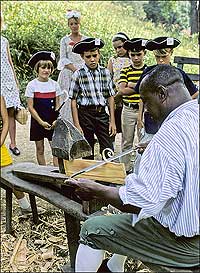

The 1957 Annual Report said the crafts program essentially is part of a broad experiment to reveal eighteenth-century Williamsburg in the light of human personalities—to make modern visitors truly feel the companionship and presence of the people who proclaimed the rights of man in words and deeds no American should ever forget. In this light, that society may be seen as not only the gifted, the articulate, the famous, but as men and women who lived useful daily lives, who scolded their children, who knew illness and good fun, toil, ambition and sorrow.

The 1960s and 1970s were golden years for Colonial Williamsburg crafts. Under the leadership of Bill Geiger and, later, Earl Soles, they flourished.

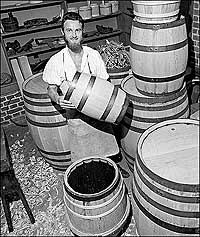

More shops opened, often led by an artisan who already had mastered the trade. Among them were Joe Grace, clockmaker; Wallace Gusler, gunsmith; Art Devletian, leatherworker; George Pettengell, cooper; George Wilson, musical instrument maker. The Geddy House and Foundry opened, providing an opportunity to show the domestic and working life of a Williamsburg family of artisans. A program of seasonal trades, among them flax breaking, papermaking, and shingle making, began.

By the early 1970s, the program presented thirty-six crafts, and employed seventy-three craftspeople and sixty interpreters. There was a growing emphasis on thorough historical research, archaeological findings, and studies of original eighteenth-century products. Much of the folklore that had before characterized interpretations was replaced with technical exactness and expertise. Colonial Williamsburg's craft program was no longer merely showing old trades. It was taking a trend-setting role in preserving skills and knowledge that were being lost.

The foundation published The Crafts of Williamsburg. The 1967 Annual Report was dedicated to the crafts. Trades pamphlets were published, and, most influential of all, craft shop films were produced: The Cooper's Craft, Basketmaking in Colonial Virginia, Gunsmith of Williamsburg, Silversmith of Williamsburg, Hammerman in Williamsburg, and The Musical Instrument Maker of Williamsburg.

In 1973, the Crafts Department opened Prentis's and Tarpley's stores as sales centers for items made in the craft shops. Across-the-counter sales were removed from the shops, and, for the first time, admission to the shops required a ticket.

During the next dozen or so years the wheelwright shop opened, kitchen programs expanded into foodways, seasonal woodworking activities became the housewright and carpentry program, period agriculture was undertaken at Carter's Grove, Colonial Williamsburg's James River plantation, and then in the Historic Area. The brickmaking program was revitalized.

In the late 1980s, the Crafts Department changed its name to the Department of Historic Trades to better reflect the use of eighteenth-century terminology. The word "craft" during the eighteenth century was most often used in the sense of "crafty" or "craftiness." The more common terms for people who made things were mechanics, tradesmen, and artisans. The Geddy youth program began so that young people could become costumed volunteers while they were introduced to the trades and to the art of interpretation. All the while, administrators and artisans were thinking more about who they were and what they wanted to accomplish.

Guests tend to go away from Colonial Williamsburg thinking that historic tradespeople are do-ers, and that is good. But underlying their activities are philosophical concerns that have to do not just with how they spend their days in eighteenth-century shops, making things in ways that most folks regard as curious and quaint, but with what they, as a group of artisans and historians, hope to achieve.

The discussions were, and are, never-ending, but the goals can be summarized quickly. The program preserves not only what is known about early trades, their products, and techniques, but also, as important, the physical ability of individuals to effectively and efficiently perform the skills involved, and therefore the nature of preindustrial work. Through documentary and hands-on research, the program strives to expand knowledge of the trades and their products and incorporate that knowledge into hands-on skills and techniques. Trades' technology-based research often results in insights into eighteenth-century attitudes and approaches to work and products that are impossible to discover through traditional curatorial connoisseurship or documentary research. The only way to accomplish these preservation and research objectives is through practice of the trades. Historic Trades makes things, a lot of things. And, finally, and of utmost importance, it must present what it is doing—physically, intellectually, and philosophically—to guests.

Among the department's recent accomplishments are: construction of the Peyton Randolph kitchen and outbuildings; establishment of a long-overdue tailoring program; expansion of the brickmaking program to include other masonry trades such as bricklaying, lime burning, and plastering; and the launch of construction and agricultural activities at Great Hopes Plantation. The department partnered with the products division to retail shop products. Trades products are becoming ever-more accurate re-creations of eighteenth-century goods. Interpretations are broader, placing trades and technical history within wider social, economic, and cultural contexts.

In the process, however, Historic Trades is realizing how fragile the program is. Some Colonial Williamsburg artisans are the only practitioners of these eighteenth-century trades. If the thread of knowledge and skills is broken, it will be impossible to start over. The Historic Trades program is people; the current generation of artisans must train the one to follow.

There is another, at least equal challenge. The patriotic pilgrimages of the 1950s gave way to the skepticism of the 1970s and 1980s. That change required that the trades program change. Today the world is changing at break-neck speed. Television, the Internet, and high-tech amusement parks bombard us with the virtual. No longer are kids routinely exposed to physical labor or to processes that most Americans over fifty learned when they grew up—a bit of sewing, cooking, shade-tree mechanics. One of the challenges is persuading guests that tradespeople are not pretending, that their fires are really fires, and, yes, they get out there and hammer and saw and stitch and dig, and like hundreds of generations before the last three or four, many of them are cold in winter and sweat during the Williamsburg summers.

If Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Trades program can hold

on to what has been achieved and refine it and expand it judiciously, the

program and the foundation are positioned for the future—to demonstrate not

only an accurate picture of life in the eighteenth century but also the

validity of technologies that offer alternatives to those of the twenty-first

century and the ability to achieve some of the educational goals set out in the

1930s that appear even more urgent today. When folks tire of the virtual and

again seek the real, Historic Trades is here.

Enlarge the portrait of Director of Historic Trades Jay Gaynor, and roll over the dots for a closer look at the work of Colonial Williamsburg's tradesmen.

Historic Trades Slideshow

Jay Gaynor, Colonial Williamsburg's director of Historic Trades since 2001, served the previous twenty years as the foundation's curator of mechanical arts. He curated the 1994 exhibit TOOLS: Working Wood in 18th-Century America at the DeWitt Wallace Museum and is a past president of the Early American Industries Association.