Online Extras

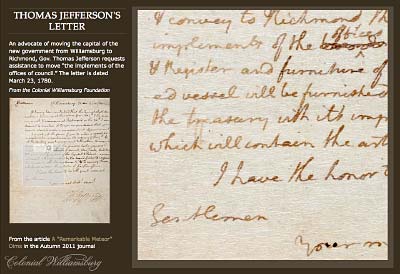

A Letter from Thomas Jefferson

The College of William and Mary

A nineteenth-century watercolor paints Williamsburg in ghostly detail, its main street nearly deserted and a green for grazing.

Colonial Williamsburg

Scenes from a Rip van Winkle village, with remnants of the eighteenth century, the Courthouse

A “Remarkable Meteor” Dims

How Williamsburg Fared as the Eighteenth Century Faded

by James Breig

In one of the last of the eighteenth-century Virginia Gazettes published in Williamsburg, the March 11, 1780, issue of Dixon and Nicolson’s weekly, a correspondent mentioned a “remarkable meteor seen here a little after sunset on Sunday the 31st of October last.” The heavenly fireworks over a town that had been center stage in America’s Revolutionary drama could have been interpreted as the portent of the passing of an era.

Virginia’s government, headquartered eighty-one years in Williamsburg, had made Richmond the state’s new capital. Since 1699, when Governor Francis Nicholson moved himself and the colony’s General Assembly in from Jamestown, Williamsburg had been the scene of events that shaped the eighteenth century; the center of political, religious, and educational life in Virginia; and the town where individuals–George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and Patrick Henry among them–took up their roles in the fashioning of a nation.

Then, in one person’s lifetime, it was over. The March 25, 1779, Gazette reported that the Business of Government . . . will cease to be transacted at Williamsburg from the 7th of April next, and will commence at Richmond on the 24th of the same Month.” June 12, 1779, the assembly passed “an Act for removing the Seat of Government to Richmond.”

Edmund Randolph, destined to become attorney general and secretary of state in President Washington’s cabinet, posted this notice in the January 19, 1780, Gazette: “I propose to remove from this place to the neighborhood of Richmond town.” Many would follow the James River northwest to the end of navigation at its fall line. Dixon and Nicolson themselves packed up their presses because so much of their news and advertising came from the government. In their final Williamsburg issue, the printers told “their good readers in the lower parts of the country . . . that they propose removing their office to the town of Richmond immediately.”

Today’s Colonial Williamsburg guests can read on Christiana Campbell’s Tavern menus that its proprietor retired in 1780 rather than follow the government inland. But proprietors of other businesses, as well as clerks, appeals courts personnel, tradesmen, lawyers, and long-time residents–even Bruton Parish Church’s organist–eventually removed. Williamsburg could still count on the economic benefit of the state activities, but its star was fading.

Phillip Hamilton, a history professor at Christopher Newport University in Newport News, Virginia, said, “There were several reasons for moving the capital. First of all, everyone knew Virginia's center of population was moving westward toward the Piedmont region and that a more centrally located center of power would eventually be needed.

“Secondly, military defense. Many Virginians thought Williamsburg too near the Chesapeake Bay and its major rivers for comfort because all these waterways were controlled by the British Royal Navy throughout the war.

“The debate over moving the capital was very bitter. Many Tidewater leaders and planters did not want to commute to the new capital. John Page of Rosewell, Virginia’s lieutenant governor in 1780, resigned his office rather than commute to the west. Other Tidewater leaders also refused to serve afterwards. Another reason given for opposing the move was the significant cost involved in moving and establishing new public buildings.”

Jefferson, the newly elected governor, backed the advocates of removal: “He was actually one of the move’s strongest advocates. In 1776, when a member of the General Assembly, Jefferson had authored and submitted a bill to the legislature to relocate the capital, but it was narrowly defeated. Jefferson had not liked Williamsburg since his college days at William and Mary, and he was very anxious for the move to occur. He did not think the town was adequate to be the capital of the new republican government.”

Robert A. Carter, senior historian with the Virginia Department of Historic Resources, said, “As war governor in 1780, author of the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom and later founder of the University of Virginia, Jefferson more than any other Virginian of his era was instrumental in moving the state capital to Richmond, separating church and state from the Anglican establishment in Williamsburg, and creating a secular rival to the College of William and Mary in Charlottesville. Each of these measures struck repeated blows to the city’s growth and prosperity in the early national period.” The college’s secular rival was the University of Virginia.

Timothy E. Morgan, in Williamsburg: A City That History Made, wrote that the town “lost its glitter, the county its wealth. Roughly half the population disappeared after 1783.” Government buildings were put to new uses. The Governor’s Palace became a hospital for troops wounded in nearby battles. Christmas Eve 1779, the legislature conducted its last session at the Capitol. The building took in an admiralty court, served as a military hospital, then a law school, then a grammar school, and finally its site was given over to a female academy.

The city retained the College of William and Mary, and Bruton Parish Church. But the school had a small enrollment and had lost two main sources of revenue–the British crown and the Anglican Church. Bruton’s influence diminished when its preachers no longer offered moral guidance to Founding Fathers. Morgan said it “lost its position as Virginia’s social and religious arbiter.” Bruton was shorn of not only the same financial support as the college, he said, but some of its income-producing property when the legislature voted to take the glebe lands of all the state's Anglican parishes and sell them.

On the other hand, the Public Hospital for Persons of Insane and Disordered Minds, which opened in 1773, expanded. In 1790, recounts another historian, “Fences ten feet high and eighty feet long were added to each end to provide exercise yards for both sexes, and staircases were built at the ends of each hall. In 1799, two dungeon-like cells were dug ‘under the first floor of the hospital for reception of patients who may be in a state of raving phrenzy.’”

Records of the King’s Arms Tavern show that its owner was regularly whitewashing rooms, “mending Plastering,” fixing chimneys, repairing walls, and shoring up the porch. Humphrey Harwood, a builder and brickmaker, jotted in his 1786 account books for William and Mary that he provided hundreds of bricks and scores of bushels of lime, laid a kitchen floor, repaired plaster and laths, whitewashed rooms, set an arch over a door, and built an oven.

As a Colonial Williamsburg historian wrote, “The population dropped. But it was still a county seat; it had its Hustings Court; the Public Hospital grew. One could not travel overland from Hampton to Richmond without passing through Williamsburg. The town provided food and lodging to such travelers.”

Indeed, not all businesses copied the Gazette’s desertion. There were still people in town to feed, house, clothe, cure, and cater to. For example, Garnier and Hubac, merchants on Duke of Gloucester Street, took out an ad in 1780 to tell buyers, “They have for sale several kinds of dry goods. . . . They also have one stage-waggon three horses, and two new harness for sale.”

Still, Williamsburg’s fortunes declined as the 1700s counted down. “The city declined very quickly after the Revolution,” Hamilton said. “There was a great deal of damage to the town and surrounding countryside.”

In 1793, the legislature passed an act to address the “ruinous Condition” of the Capitol and authorized town officials to sell its west wing to raise funds to repair the remainder. In 1832, what was left burned down.

The Palace, once the stately center of so much of the city’s life, burned down in 1781, presaging loss and decay to come. The Palace’s “ruins remained a sign and symbol of the city’s past glories,” Morgan said, “which everyone realized were not about to return.” When Governor Dunmore’s grandson, Sir Charles Augustus Murray, visited in 1835, he wrote: “The centre of the palace where the governor resided has long since fallen down, and even the traces of its ruins are no more to be seen.” Morgan described life in Williamsburg as “slowly settling into the rural routine” by which it “became a small-town county seat.”

Jedidiah Morse, preparing his American Universal Geography, toured the United States and visited Williamsburg in 1792. He reported:

Every thing in Williamsburg appears dull, forsaken and melancholy–no trade–no amusements, but the infamous one of gambling–no industry, and very little appearance of religion. The unprosperous state of the college, but principally the removal of the seat of government, has contributed to the decline of the city.

Jurist St. George Tucker, who lived across Market Square from the courthouse, wrote a pamphlet in rebuttal under the name “Citizen of Williamsburg.” Tucker, who asked how a “universal” geography could focus on only one-fourth of the world, wondered why Morse, a minister, lacked “that charity which his divine master taught was the first of virtues.” What Morse had missed, he said, was that Williamsburg

was the residence of three ministers of the gospel, a judge who now graces the bench of the supreme court of the United States, and of the chancellor of the state of Virginia. . . . Figure to yourself, gentle reader, this groupe employed at the infamous amusement of gaming! Imagine them . . . occupied in cheating, sharping, palming, swearing, and doing every other opprobrious act.

Tucker asked how Morse could allege that there was no sign of religion in Williamsburg: “Did he expect to see a procession like the triumphal entry of St. Rosolia at Palermo; or the elevation of the host at Rome?”

Tucker said Williamsburg’s houses were “pleasantly situated . . . neat and comfortable; most of them had gardens.” Tucker did not know what apology Morse could make for his “unprovoked attack. . . . If in any future edition . . . should think proper to bestow a paragraph on Williamsburg, it is to be hoped, that he will at least expunge all that he had said respecting the moral and religious character of the inhabitants.” Morse did.

But Tucker could not conceal the truth. “Not a few private houses have tumbled down; others are daily crumbling into ruin,” he said. He hoped that “Williamsburg had seen its worst days.” And if actions speak louder than words, Tucker’s own move to Richmond in 1803 was vociferous.

In 1796, Williamsburg visitor Isaac Weld Jr. wrote that “the Houses . . . present a melancholy Picture,” and described Bruton Church as “much out of Repair.” A Venetian nobleman who visited in 1806 said, “What lovely houris to come out of such wretched hovels!” a houri being a voluptuous woman.

In 1824, Daniel Walker Lord of Kennebunkport, Maine, stopped at Bruton Parish Church, and wrote: “There is a burial ground around it. Some of the tombs are marked as early as 1693. . . . The tombs in the yard have most fallen down, and look as though their friends are all extinct.”

On the eve of the Civil War, the Southern Literary Messenger wrote of Williamsburg:

This old town, now a quiet and sleepy village, with only the life and animation imparted by the college and its inmates, was once the scene of Virginia’s greatest social refinement, hospitality, statesmanship and literature. Its history is so full of great incidents, that one is surprised to contrast the bright narrative with the dull and dozing appearance of the present town.

A half-century later, things had not much changed. In 1907, Mayor George Coleman wrote:

Williamsburg on a summer day! The straggling street, ankle deep in dust, grateful only to the chickens, ruffling their feathers in perfect safety from any traffic danger. The cows taking refuge from the heat of the sun, under the elms along the sidewalk. Our city fathers, assembled in friendly leisure, following the shade of the old Court House around the clock, sipping cool drinks, and discussing the glories of the past. Almost always our past! The past alone held for them the brightness which tempted their thought to linger happily.

Hamilton said, “The town was never again as active and interesting as in the pre-1780 period. Indeed, William and Mary declined along with the town itself. Williamsburg was in the middle of a tidewater region, which itself was economically stagnant in the decades after the Revolution. Without serving as the capital of the government, it was almost impossible for Williamsburg to regain its former energy.”

There were spurts of activity–as in 1781, when Washington’s troops garrisoned the city after beating the British at Yorktown, or in 1862, when Union soldiers occupied the town, or in 1881, and in 1916, when a new gun-cotton factory flooded Williamsburg with laborers, and in 1918, when the college embarked on an ambitious expansion–but the town seemed never to revive.

Yet, as Hamilton says, “Williamsburg did not end up like Jamestown, which completely disappeared as a town after the capital moved to Williamsburg.”

The city’s slumber proved to be its salvation. The Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin woke up to the idea that in Williamsburg’s past lay its future. College fund-raiser, and Bruton rector, Goodwin saw in the houses and stores that lingered from the city’s 1700s the prospect of revival. In 1927, he persuaded John D. Rockefeller Jr. to buy a share in his dream. Together they brought new life, old glory, and restoration to an old colonial capital.

James Breig an Albany-based writer and editor, contributed to the winter 2011 journal an article on eighteenth-century letter writing.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Rutherfoord Goodwin, A Brief & True Report concerning Williamsburg in Virginia (Richmond, 1941)