The Eighteenth Century Goes to the Dogs

by James Breig

A bulldog named Glasgow, here portrayed by Pugsley, missing from the Governor's Palace compound, elicited a twenty shilling reward in 1774.

Glasgow had gone missing. A brown-and-white bulldog with an iron collar, he usually growled and snoozed behind the Governor's Palace walls in Williamsburg. But one day in 1774, he disappeared, stolen it seemed, from the Palace grounds. That his name, breed and description survive is an indication of a gathering shift in attitudes toward man's best friend, attitudes reflected in the lost-and-found advertisements of the Virginia Gazette. The name of Glasgow's owner is forgotten, but for his return, twenty shillings was offered, a sum that underscored his master's attachment. It was not so substantial a reward, however, as the $20 posted in 1777 for a pet Pomeranian called Spado. Spado's notice, inserted by Williamsburg's William Finnie, said the shaggy little black canine had been spotted in the possession of a man who called himself Joseph Block, but "belongs to our brave but unfortunate general LEE." The general in question may have been Charles Lee, a gentleman seldom seen without his dogs, who was captured by the British in 1776. Perhaps more typical is a 1752 advertisement for Ball, a reddish spaniel missed by owner James Spiers, who was willing to part with a dollar to get him back.

The relationship between people and pooches had been evolving, time out of mind, since the dog's domestication. An animal perhaps initially valued for its service was becoming man's best friend. A turn through Bartlett's suggests something of the long transition. The Romans had a proverb, cave canem—beware of the dog. In the seventeenth century, Shakespeare employed the nouns "dog" and "cur" as terms for unworthy persons. But in 1738, Benjamin Franklin could write, "There are three faithful friends—an old wife, an old dog, and ready money." Lord Byron, in 1808, penned an inscription for a monument to a dog that read in part:

The poor dog, in life the firmest friendAnd in 1825, Sir Walter Scott wrote, "Recollect that the Almighty, who gave the dog to be companion of our pleasures and our toils, hath invested him with a nature noble and incapable of deceit."

The first to welcome, foremost to defend

Age by age, canines claimed more and more of man's love. Eighteenth-century newspaper ads tell a sliver of the story of the evolution of the relationship. Elsewhere in the era there were elegies for deceased dogs, paintings of pointers and pugs, careful breeding, and a philosophical declaration about the rights of dogs under the law.

This is not to say that all dogs lived a dog's life. Bull- and bearbaiting were still popular in the eighteenth century. Packs of dogs were turned into a ring to harass larger animals by biting them in vulnerable spots and holding tenaciously to their snouts, a maneuver called "pinning the bull," a specialty of bulldogs. The events—common in England, where they attracted thousands of fans—were bloody.

Outside the ring, dogs could be a threat to gentler livestock. A 1769 petition to Virginia's House of Burgesses from King and Queen County begged "to lay before you the great injury and loss that we sustain in our flocks of sheep, by the dogs which are suffered to run at large...'Tis notorious that the dogs are worse than" wolves.

These antique ceramic dogs in the Colonial Williamsburg collections were imported from England. The one in front is harrying a pair of chickens.

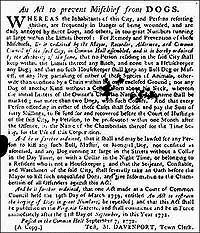

Natural aggression and a tendency toward annoyance could make dogs something of a discomfort to humans, too. In 1772 the city fathers of Williamsburg passed the Act to Prevent Mischief from Dogs, which forbade anyone to own a bitch within city limits. Homeowners were permitted to keep up to two male dogs if they wore collars marked with their owners' initials. Any dog not meeting those requirements was to be killed.

Rabies was on people's minds. A 1793 issue of the Massachusetts Magazine or Monthly Museum ranks the disease among the most mortal horrors:

The apprehension of war, the report of the plague, the dread of a mad dog, or of a comet, alternately fill every countenance with gloom, every heart with terror, and every tongue with lamentation and complaint.As the King and Queen County petitioners suggested, dogs and wolves are closely related. Thousands of years ago, however, humans began to domesticate some wolves—inventing dogs, first as partners and eventually as pets. Through the millennia, dogs have borne burdens, herded livestock, drawn sledges, carried messages, tracked fugitives, retrieved game, and guarded their owners. The relationship evolved from a purely practical "you help me; I feed you," to mutual affection.

As the eighteenth century approached, that development could be seen in the use of dogs as main characters in literature. In 1613, for example, Cervantes wrote The Dialogue between Scipio and Berganza, a novel about two Spanish dogs. Later in the century the French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine wrote "The Little Dog," a lengthy poem about a man who is changed into a woman's pet. In the mid-1700s, Francis Coventry penned The History of Pompey the Little: Or, the Life and Adventures of a Lap-Dog. Chapter four of the humorous novel is titled "Our hero becomes a dog of the town, and shines in high-life." In his seventeenth-century diary, Samuel Pepys tells the story of traveling on a barge with Charles II and "a dog the King loved" that fouled the boat ("which made us laugh, and me think that a King and all that belongs to him are but just as others are"). Pepys was not so amused by his wife's dog, which he threatened to "fling ...out of window" if it dirtied the house anymore. Charles II was so devoted to his canines that he let them distract him during meetings, leading a courtier to growl: "God save your Majesty, but God damn your dogs."

Canines entered the art world in a new way. Though generic dogs had been depicted in paint and carved in stone for millennia, paintings of specific dogs began to be done in the two or three centuries preceding the 1700s, mostly the favored lapdogs and hunting hounds of royalty. One art expert designates The Arnolfi Marriage, a 1434 painting by Van Eyck, as the first human portrait to include a pet. The seventeenth and eighteenth centuries saw a boom in portraiture of pups: Emperor Joseph I as a child with a cocker spaniel; Louis XV's daughter with a large book and a tiny Papillon; the Princess Royal and Prince William around 1770 with a shih tzu; and George III's wife, Queen Charlotte, with a Maltese in one portrait and a spaniel in another. When William III, after whom Williamsburg is named, moved from Holland to London to rule Great Britain, he brought along pugs, a favored pet and symbol of the Netherlands. So beloved did the tough little dogs become that William Hogarth's self-portrait includes his pug Trump.

Dogs were also limned on their own, most notably by George Stubbs, whose eighteenth-century portraits of horses and dogs are considered best of show by many critics. Stubbs reflects in art what was evolving in science, says Malcolm Warner, a senior curator with the Kimbell Art Museum in Fort Worth, Texas. In 2004-5, he is curating a major Stubbs exhibition there that is to travel to Baltimore and London. "Descartes had argued that when you hear an animal cry out in pain, it's like a machine's noise when its gears go wrong," he says. "In the eighteenth century, there was a huge improvement in scientific knowledge, and people began to think of animals as creatures with feelings and personalities comparable to people." Stubbs filled a need to capture those personalities on canvas. The results were images of Mouton, a barge dog; the spaniel Fanny; Turk and Crab, a duke's Pomeranian and terrier; and Faddle, A Spaniel.

Other painters specialized in this genre, among them Thomas Gainsborough, who put dogs into his portraits. In France, Jean-Baptiste Oudry exhibited Bitchhound Nursing Her Pups in 1753. It has been credited by one modern critic as pinpointing "the moment when that all-embracing empathy between man and dog was first recorded so fully and so tenderly in a canine environment."

Dogs became so beloved that their deaths elicited elegies. One of the first came from Matthew Prior in 1693 to mark the loss of True, a pet of Queen Mary II:

Envious Fate has claim'd its due,In 1775, Williamsburg's Virginia Gazette printed "On the Death of a Lady's Dog":

Here lies the mortal part of True.

John Gay published "An Elegy on a Lap-Dog" in 1720:

He's dead. Oh lay him gently in the ground!

And may his tomb be by this verse renown'd.

Here Shock, the pride of all his kind, is laid;

Who fawned like man, but ne'er like man betray'd.

Thou, happy creature, art secureOne reason this attentiveness to dogs arose during the 1700s is the Enlightenment, which "made it more acceptable to engage in humanitarian activities, whether for people or animals," says Stanley Coren, author of The Pawprints of History: Dogs and the Course of Human History. Warner refers to a

From all the troubles we endure.

deep philosophical shift, in eighteenth-century Britain in particular, that led people to think of animals as having a value in their own right. Previously, they had been thought of in terms of their usefulness to mankind—as objects more or less.During the Enlightenment, as scientists learned more about animals, "people became more sensitive to animals' pain, and that merged into a feeling that they were individuals with personalities and emotions."

A 1735 portrait of William Byrd II's daughter Anne, attributed to Charles Bridges, includes her fond and faithful pet.

Coren, a professor of psychology at the University of British Columbia, says there was another factor in this shift: the rise of an affluent middle class. "They could express their status in purebred dogs," he says. "And once dogs were in the parlor and out of the yard, affection grew for these beasts. They were treated more as family members." He is supported by Robert Fountain, co-author of Stubbs' Dogs: The Hounds and Domestic Dogs of the Eighteenth Century as Seen through the Paintings of George Stubbs. Fountain credits the growing attentiveness to dogs to "the ambitions of the upwardly mobile to become country gentlemen and improve their social standing by participating in field sports, whether they enjoyed it or not."

The expanding love of humans for canines was endorsed by eighteenth-century philosophers, playwrights, poets, and preachers. Voltaire said that "the best thing about man is the dog;" Alexander Pope said that "histories are more full of examples of fidelity of dogs than of friends;" and Robert Burns wrote that "the dog puts the Christian to shame." The connection between Christianity and the protection of animals was stated in depth by Humphrey Primatt, an Anglican clergyman. In 1776, he published what amounted to a Declaration of Independence for beasts. In A Dissertation on the Duty of Mercy and Sin of Cruelty to Brute Animals, Primatt wrote:

See that no brute of any kind ...suffer thy neglect or abuse...Let no views of profit, no compliance of custom, and no fear of ridicule of the world, ever tempt thee to the least act of cruelty or injustice to any creature whatsoever.What disturbed people was not just bullbaiting and cruel owners but animal experimentation and vivisection. One of the most acclaimed surgeons of the time, Dr. John Hunter, conducted research in 1755 on artificial respiration in hopes of finding a way to revive people who had drowned. His experiment involved using bellows to repeatedly resuscitate a dog, and cutting its sternum open to see how its lungs and heart were responding. A 1789 footnote by philosopher Jeremy Bentham has become what Warner terms "a landmark in the history of animal rights"; indeed, it turns up in modern-day literature from groups like People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals. Bentham wrote:

A full-grown horse or dog is beyond comparison a more rational, as well as more conversable animal, than an infant of a day or a week or even a month old. But suppose they were otherwise, what would it avail? The question is not, Can they reason? nor Can they talk? but Can they suffer? Why should the law refuse its protection to any sensitive being? The time will come when humanity will extend its mantle over everything which breathes.In Japan, that had already happened. In the middle of the seventeenth century, a shogun—who was born in a Year of the Dog—instituted Laws of Compassion to protect canines. He decreed that anyone mistreating a dog would face capital punishment. In England in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, one of the leaders in the movement to safeguard animals was an Irish Protestant who campaigned in Parliament for Catholic emancipation and the care of animals. Richard Martin, born in 1754, was nicknamed "Trigger Dick" for his duels, one occasioned by his opponent's shooting of a dog. But Martin later became known as "Humanity Dick" for his efforts on behalf of farm animals, which led not only to laws but to the founding of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals.

Another sign of interest in dogs in the 1700s was the development of breeding techniques. Modern-day breeders have an eighteenth-century Italian priest to thank for advances in their field. Father Lazzaro Spallanzani knew about philosophy, logic, metaphysics, physiology, Greek— and how to artificially impregnate animals. He is considered the first scientist to accomplish that feat, and he used a dog to prove it could be done. But breeders in the 1700s still did things the natural way, mixing and matching dogs through mating to get the characteristics they sought.

Dogs on DOG Street: Wendy Perry and her bull mastiffs exercise their ten legs on the Duke of Gloucester Street.

The first official classification of English breeds was done in 1570 by John Caius in De Canibus Britannicis, or Of English Dogges. Among other types, he identified bloodhounds and terriers, otter hounds and Maltese. During the eighteenth century, an era of taxonomies and catalogues, Buffon and Linnaeus expanded on Caius, with Linnaeus listing such animals as the Shepherd's Dog, the Pomeranian, the Iceland Dog, the Lesser Water Dog, the Mastiff, and the Barbet. It was on such stock that breeders of the eighteenth century went to work to improve toy poodles for milady, clench-jawed bulldogs for bullbaiters, faster greyhounds for racing aficionados, and dotted Dalmatians for carriage drivers. Fountain writes that "established landowners became more and more preoccupied with breeding better livestock, faster horses and hounds, and dogs better suited to the changing style of shooting as the accuracy of firearms increased."

The rise in fox hunting in both England and its American colonies spawned a need for a medium-sized hound with the stamina to follow prey for miles, a keen nose for scent, and a bark that could summon his master from a distance. In England, one of the leading eighteenth-century breeders of foxhounds was Hugo Meynell, who outlined the breed's traits and kept strict records to produce offspring that could keep up with foxes. Foxhounds came to Virginia in 1738 with Lord Fairfax, and the breed fascinated a Fairfax familiar, George Washington, whose pets had names like Sweet Lips, Venus, and True Love. Washington's diaries are crammed with notations about riding to the hounds. One January, he spent eight days pursuing foxes—often, he "catched nothing"—and two other days borrowing dogs from neighbors. His love of canines was so strong that during the Revolutionary War, he went to the bother of returning a stray terrier to its owner, British General Howe, along with a note that read: "General Washington does himself the pleasure to return ...a dog, which accidentally fell into his hands."

In 1772, Washington's friend Bryan Fairfax said that the American general was so discerning he could pick out the inferior pups from what others considered "superexcellent dogs." Thomas Jefferson did not share his fellow Virginian's attachment to canines; nonetheless, in 1789, returning from his stint as ambassador to France, he imported "shepherd's dogs" for Monticello and later presented Washington with puppies. For his part, Washington fixated on perfecting the English foxhound. To that end, he built kennels at Mount Vernon where he could create "a superior dog, one that had speed, scent and brains." Washington's experiments led to the American foxhound, which is lighter, taller, and faster than its British cousin.

Glasgow, Spado, and Ball, the dogs of eighteenth-century Williamsburg, have their twenty-first-century counterparts. Modern guests of Colonial Williamsburg walk their pooches between Bruton Parish Church and the Capitol. That's in keeping with the dream of Rev. W. A. R. Goodwin, the Bruton pastor whose efforts led to the restoration of the former Virginia colonial capital. According to a report from a 1992 conference at Colonial Williamsburg, Goodwin—who owned a dog named Alaska—imagined scenes of "the olden days," featuring a stagecoach with a footman, for example, or maybe gentlemen in hunting clothes surrounded by their dogs. It's entirely appropriate, therefore, that today's visitors parade their pets down Duke Of Gloucester Street—or, as it's known to the locals, DOG Street.

Williamsbur-grrrs: The dogs of early Virginia

There were dogs in the New World, long before the arrival of Europeans; archaeologists have found more than 100 dog skeletons where woodland Indians lived during the centuries before Jamestown's founding.

Bones from later periods provide evidence that there were plenty of dogs in eighteenth-century Williamsburg and its environs. The Virginia Gazette often carried advertisements for lost dogs. In 1751, for instance, Alexander Finnie, who ran the Raleigh Tavern, offered to pay "Half a Pistole" to anyone who returned his "spaniel BITCH, with white and brown spots."

Then there are the mysterious bones unearthed by Colonial Williamsburg's restoration team near the Geddy House on Duke of Gloucester Street. In a report on excavations there in 1966 and 1967, archaeologists said that they found, in the kitchen-laundry outbuilding, "a grave filled with gray clay and ashes and containing a dog skeleton, no datable artifacts, sealed beneath southeast cheek of chimney."

Like the frozen leopard at the beginning of Ernest Hemingway's The Snows of Kilimanjaro, no one knows why the dog was there.

Canine Quiz

Canine Quiz

Test your knowledge of historic figures and their canine companions.

James Breig, an Albany, New York, editor and writer, contributed a story about colonial lotteries to the spring 2004 journal. Read his article "Early American Newspapering" from the spring 2003 journal.