Early American Newspapering

by James Breig

Facsimile of the first and only issue of the English-American colonies' first newspaper, published in Boston 1690.

We are here at the end of the World, and Europe may

bee turned topsy turvy ere wee can hear a word of it.

-Virginia planter William Byrd, 1690

In seventeenth-century America, colonial governments had rather do without newspapers than brook their annoyance. In 1671, Governor William Berkeley of Virginia wrote: "I thank God, there are no free schools nor printing and I hope we shall not have, these hundred years, for learning has brought disobedience, and heresy, and sects into the world, and printing has divulged them, and libels against the best government. God keep us from both." As the British government once told the governors of Massachusetts, "Great inconvenience may arise by the liberty of printing."

Not until 1690 did the first English-American news sheet debut—Boston's Publick Occurrences Both Forreign and Domestick, published by Benjamin Harris. The authorities, in "high Resentment" that Harris dared to report that English military forces had allied themselves with "miserable" savages, put him out of business four days later.

By the end of the eighteenth century, however, scores of homegrown broadsheets and tabloids satisfied the information appetites of Americans hungry for intelligence of the Old World, for news about the Revolution, and for the political polemics of the infant United States. The history of newspapering in that century digests the beginnings of much of what is served on newsstands in this one.

As the century began, the fledgling colonial press tested its wings. A bolder journalism opened on the eve of the Revolution. And, as the century closed with the birth of the United States, a rancorously partisan and rambunctious press emerged.

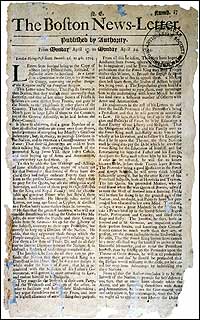

The eras can be traced in the history of the family of Benjamin Franklin—the preeminent journalist of his time. But it best begins with another Boston newspaperman, postmaster John Campbell. In 1704, Campbell served up The Boston News-Letter, the nation's second paper. It was a publication the powers-that-be could stomach. The News-Letter lasted seventy-two years, succeeding in an increasingly competitive industry, supported by the growth of communication and of commerce.

Campbell's fellow postmasters often became newspaper publishers, too; they had ready access to information to put on their pages. Through their offices came letters, government documents, and newspapers from Europe. Gazettes were also started by printers, who had paper, ink, and presses at hand. Franklin was a postmaster and a printer.

Boston News-Letter from American Antiquarian Society. "Numb. 1" of the colonies' second paper, which lasted seventy-two years. It was also published in Boston.

Eighteenth-century editors filled their columns with items lifted from other newspapers—"the exchanges," as they are called still—and from letters, said Mitchell Stephens, a New York University journalism professor and the author of A History of News. European news, taken from newspapers that arrived in ports like New York, Philadelphia, and Charleston, got good play. The November 8, 1797, issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette, for example, carried this item from New York: "Yesterday arrived here the ship Mary. . . . By this arrival we are furnished with London Papers . . . from which the most important intelligence is extracted." David Sloan, a University of Alabama journalism professor, lists the sources of stories as "European newspapers, primarily English ones; correspondence sent in by readers; other newspapers in the colonies; and individuals who would drop by the print shop and talk."

Julie K. Williams, a history instructor at Alabama's Samford University, said publishers had such altruistic motives as improving communication and educating the public, but profit was their primary purpose. Maurine Beasley, a University of Maryland journalism professor, puts it plainly. The purpose of newspapers was "to make money."

Williams said, "Newspapers brought in ad revenue and circulation revenue." That income supplemented receipts from books, government printing jobs, merchant invoices, forms, and other ephemera.

Making money is still what keeps newspapers in business, and that is but one similarity between eighteenth-century papers and the twenty-first's. As Sloan said, "Newspapers are still printed with ink on paper." But more than that, newspapers then and now "still have opinions and letters. There was a sense then that newspapers should publish both sides of an issue, even during the Revolution and factional periods."

Williams ticks off the surface differences in the newspapers of the two centuries—there were no headlines and few illustrations then, for example—as well as cosmetic similarities. "You can look at an eighteenth-century newspaper and recognize the column layout and the general news-ads look of a paper today," she said. "It is interesting that the 'look' is still basically there.

"But the biggest similarity is what news is. We decided in the eighteenth century that newspapers were about 'occurrences,' and basically we have stuck to that. I think 'departments' are clearly an idea in the eighteenth century. The colonial printer had a standing format that he followed religiously that involved dividing the news by type. These sections were often labeled 'foreign reports' and so on."

To Carol Humphrey, an Oklahoma Baptist University journalism professor and secretary of the American Journalism Historians Association, "The primary legacy of the eighteenth century for modern journalism is the right to comment on political events. The modern-day editorial has its beginnings in that era."

The DNA of modern newspapers is found in the eighteenth century, Stephens said. "The look is the same," and "the sense of what news is, is basic to human beings."

Most colonial newspapers were weeklies, had four pages, and printed most of their advertisements in back. With little space, printers kept many stories brief, encapsulating even significant information into "one short paragraph, even a sentence," Sloan said.

Newspapers also contained "essays, poems and humorous material, some of which they wrote themselves, like Ben Franklin," Beasley said. "Sometimes, items that had a sensational or religious aspect appeared, such as a report of a strange creature being sighted or some unusual event occurring attributed to 'divine providence.'"

Readers wondered about the course of wars in Europe and were curious about happenings in other towns and colonies—especially events that could affect their lives. But they were as interested as readers of today in the ordinary events of the life of their times. When they got their newspaper, subscribers perused such advertisements and news as:

Run away . . . a small yellow Negro wench named Hannah, about 35 years of age, had on when she went away a green plain petticoat and sundry other clothes, but what sort I do not know.—from a 1767 issue of Williamsburg's Virginia Gazette

For Sale—The spars, anchors, rigging, and hull, of a brig, sixty four feet keel, twenty four and a half feet beam, and ten feet hold.—from a 1782 issue of the Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser

The noted High Bred Horse Old Mark Anthony, now in high perfection, and as vigorous as ever, stands at my stable this season in order to cover mares, at £3. the leap.—also from a 1782 issue of the Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser

Last Friday, the fatal and ever memorable Day of the Martyrdom of King Charles the First, a most extraordinary Misfortune befell this Place, by the Destruction of our fine Capitol. . . . The Cupola was soon burnt, the two Bells that were in it were melted, and, together with the Clock, fell down, and were destroyed.—from a 1747 issue of the Pennsylvania Gazette,

but datelined Williamsburg, February 5.

1736 Virginia Gazette

from Virginia Historical Society. Oldest surviving copy of the Virginia Gazette,

from 1736.

When, as the century began, Campbell and his colleagues set up their forms, they entered a risky business. Printers were licensed by the government, and they could be unlicensed swiftly, and imprisoned. That happened to Benjamin Franklin's older brother James, publisher of the New-England Courant.

James Franklin inspired his sibling's interest in printing. "In 1717," the younger Franklin wrote, "James returned from England with a press and letters to set up his business in Boston. . . . My father was impatient to have me bound to my brother." The boy was at length "persuaded, and signed the indentures when I was yet but twelve years old." But like the publisher of Publick Occurrences, James Franklin ran afoul of the authorities. "One of the pieces in our newspaper gave offense to the Assembly," Benjamin Franklin said. His brother "was taken up, censur'd, and imprison'd for a month. . . . During my brother's confinement . . . I had the management of the paper."

When the government freed the older Franklin, it forbade him to print the Courant any longer. The brothers circumvented the order by putting Benjamin Franklin's name on it.

John Peter Zenger, editor of the New-York Weekly Journal, was arrested in 1734 and charged with seditious libel for criticisms of Governor William Cosby. The facts were against Zenger, but a jury more sympathetic to free speech than to authority acquitted him. Franklin, who had moved to Philadelphia, where he founded Poor Richard's Almanac and the Pennsylvania Gazette, endorsed the verdict in a couplet:

While free from Force the Press remains,

Virtue and Freedom cheer our Plains.

Typical for Franklin and his colleagues, the lines are lifted from a poem by Mathew Green, "The Spleen," published in 1737.

As happy as editors were to see Zenger vindicated, they noticed that he had spent ten months in jail awaiting trial. His wife had carried on the Journal, but clearly a newspaperman's livelihood and liberty depended on the forbearance of the government.

At mid-century, the press began to alter its stance and became more outspoken. In 1754, during the French and Indian War, Franklin published America's first newspaper cartoon, a picture showing a snake cut into sections, each part representing a colony, with the caption: "Join or Die."

Franklin became a wealthy publisher and editor. He linked print shops and post offices in a coastal chain, and spread newspapering up and down the seaboard. Newspapers founded under his aegis prospered and, as troubles with Great Britain mounted, became precisely the "great inconvenience" England feared.

Stephens said the purpose of newspapers "changed to the political and polemical after 1765—around the time of the Stamp Act-as tensions snowballed." Sloan said, "During the Revolution, the main goal was to support the American cause."

Massacre spread from American Antiquarian Society. ". . . the Blood of Our Citizens running like Water thro' King-Street"-the Boston Gazette

reported the 1770 Boston Massacre.

"Prior to the Revolution, newspapers existed primarily to inform people of what was going on in the rest of the world," Humphrey said. "The Revolution changed the focus to events in the other colonies."

Daily publication began in the 1780s, just as the new American republic emerged. There were about 100 newspapers by 1790, many of them were spirited, and some were great annoyances to men in high positions. It was a time of enormous press freedom, a freedom exercised frequently in behalf of the Federalist or Republican parties, which subsidized their own publications. Humphrey said, "Many newspapers in the 1790s were intended to accept a particular political party." Two examples are the Gazette of the United States for the Hamiltonian Federalists; the National Gazette for the Jeffersonian Republicans. "Their editors believed that they should support their particular party in all that they did," she noted, "so they wrote essays in support of their party and included editorial comments in the news pieces that either supported their party or attacked the opposition."

This was the era of Philip Freneau, John Fenno, and James Callendar, sharp-penned scribes who used their journalistic skills to laud their friends and denigrate their enemies. This was the era when government officials and political figures—Alexander Hamilton and James Madison among them—adopted pseudonyms to promote their politics in the public prints anonymously.

Many of the founding fathers were enthusiastic about a free press. Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1787 that "were it left to me to decide whether we should have a government without newspapers or newspapers without a government, I should not hesitate a moment to prefer the latter." Samuel Adams said in 1768 that "there is nothing so fretting and vexatious, nothing so justly terrible to tyrants . . . as a free press."

But newspaper partisanship had evolved from the Revolution. "Newspapers that were used to denouncing Tories and the King," Stephens said, "slid easily into denouncing opposition parties, even the President of the United States."

A glass of wine, checkers, and the latest news are tavern diversions for Colonial Williamsburg interpreters Lou Vosteen, front, and Peter Rizzo. - Photo by Dave Doody.

George Washington declared a lack of interest in newspapers before he was president, writing in 1786 that "my avocations are so numerous that I very rarely find time to look into Gazettes after they come to me." But while in office, he sometimes was incensed at what he saw in print. In notes about a 1793 cabinet meeting, Secretary of State Jefferson recorded how the president went on in such "a high tone" about the paper of "that rascal" Freneau that the cabinet officers were momentarily stunned into silence.

Benjamin Franklin's grandson and namesake, Benjamin Franklin Bache—also known as "Lightning Rod Junior"—edited the Aurora. Bache delighted in harassing President Washington, once labeling him "the source of all the misfortunes of our country" and declaring him "utterly incapable."

When John Adams wrote "A Constitution or Form of Government for the Commonwealth of Massachusetts" in 1779, he included a guarantee of liberty of the press. But as president, Adams endorsed the Alien and Sedition Acts, aimed at muzzling the opposition by jailing editors who dared criticize the chief executive.

Sloan said Bache was "a really ardent, zealous partisan. He epitomizes the intensely partisan editor." Bache was indicted under the Alien and Sedition Acts but died before his case came to trial. Adams's successor, Jefferson, released imprisoned journalists and allowed the law to lapse.

Stephens said that the free—and free-wheeling—press of the federal period helped to create the United States: "It is hard to imagine the United States arriving when it did without a free press. It was a wild, unruly press, but democracy was a great experiment and an aggressive press was part of it."

Much has changed in the centuries since Benjamin Harris set up his type. Among other things, the web press, the linotype, and, eventually, offset printing came to the business. The telegraph and news services supplanted the exchanges. The First Amendment, written originally to protect the press only from the federal Congress, was interpreted to apply to the governments of the states. Illustrations and photographs became as important as words. Journalism emerged as a diplomaed, white-collar profession. And the role of the press as a "great inconvenience" to government is a hallmark of democratic government.

"How," asks Stephens, "can you run a country without a free press?"

Jim Breig, an Albany, New York, writer and weekly newspaper editor, contributed "Out, Damn'd Proverbs: Eighteenth-Century Axioms, Maxims, and Bywords" to the winter 2002-2003 journal.