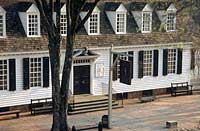

The Apollo Room in Colonial Williamsburg’s reconstructed Raleigh Tavern, where five students from the College of William and Mary met in 1776 to form the Phi Beta Kappa Society, dedicated to the pursuit of knowledge.

Courtsey of Phi Beta Kappa Foundation

Portrait of John Heath, a founder and first president of Phi Beta Kappa

Author’s PBK key, stars for friendship, morality, and learning; a finger points to scholarly ambition.

Despite the abundance of strong drink available in the Raleigh Tavern, PBK’s founders committed themselves to sobriety.

φβκ

Phi Beta Kappa

by Michael J. Lombardi

On a cold December evening in 1776, five College of William and Mary students made their way along Williamsburg’s Duke of Gloucester Street to the Raleigh Tavern. They gathered in its Apollo Room with a high purpose. They came to found Phi Beta Kappa.

The Apollo Room had seen historic meetings before. In 1769 and again in 1774 the Virginia House of Burgesses assembled at the Raleigh after governors dissolved their elected assembly. In 1773, Richard Henry Lee, Thomas Jefferson, Patrick Henry, Francis Lightfoot Lee, and Dabney Carr met in the tavern and proposed creation of a standing Committee of Correspondence—a step toward uniting the American colonies.

On this night, John Heath, fifteen years old, led five friends to the Raleigh, to foment revolution not against the crown but against the state of the college’s student societies. Phi Beta Kappa became the nation’s most important honor society, its key a coveted symbol of academic achievement, but it started with more modest aspirations.

Student societies, primarily interested in debating and philosophical discussions, were popular institutions at America’s early colleges. Yale had the Linonian Society and the Brothers in Unity, Princeton the American Whig and the Chliosophic Society. Harvard’s counterpart was the Speaking Club. Membership was large and nonexclusive. More than a third of Yale’s students belonged to the Linonian Society.

William and Mary already had two student societies, the FHC, formed in 1750, and the PDA, which appeared in 1773. Unlike their New England counterparts, they were exclusive and secret. The FHC was ultra-elite, and so secret that it allowed the outside world to know it only by its initials, presumably for a Latin phrase, Fraternitas, Hilaritas, Cognitioque, or friendship, conviviality, and knowledge. Nicknamed the Flat Hat Club, the FHC purported to be a literary and philosophic society, but often held boisterous, drunken parties. Jefferson, who attended William and Mary in the early 1760s, later wrote, “When I was a student of Wm. & Mary College of this state, there existed a society called the F.H.C. society, confined to the number of six students only, of which I was a member, but it had no useful object, nor do I know whether it now exists.” The PDA was nicknamed Please Don’t Ask. According to William Short, a Jefferson associate and an early Phi Beta Kappa member, it “had lost all reputation for letters and was noted only for the dissipation and conviviality of its members.”

So five young students met in the Raleigh determined to create a better society. The minutes from their first meeting set the tone:

On Thursday, the 5th of December, in the year of our Lord God one thousand seven hundred and seventy-six, and the first of the Commonwealth, a happy spirit and resolution of attaining the important ends of society entering the minds of John Heath, Thomas Smith, Richard Booker, Armistead Smith, and John Jones, and afterwards seconded by others, prevailed and was accordingly ratified.

And for the better establishment and sanctitude of our unanimity a square silver medal was agreed on and was instituted, engraved on the one side with S.P. (the initials of the Latin, Societas Philosophiae, or Philosophical Society) and on the other agreeable to the former with the Greek initials of ΦβΚ (Φιλοσοφι′α βι′ου Κυβερνητης, philosophy, or love of wisdom, the guide to life) an index imparting a philosophical design, extended to three stars, a part of the planetary orb distinguished.

The founders were determined to keep the new society’s secrets. In the original minutes, the Greek and Latin mottos were rubbed out and in the case of the Latin inked over, leaving only the initials, ΦβΚ and SP. The meaning of the Greek motto was not determined until 1831, and a thorough study of the documents in 1906 finally established the meaning for SP. At the second meeting on January 5, 1777, John Heath was named the first president, and the society adopted a mode of initiation that required each member to attest to “keeping, holding and preserving all secrets that pertain to [his] duty, and for the promotion of its internal welfare.” They later devised a secret handshake and a seal.

It’s likely the founders chose to create a secret society unbound by the “Scholastic Laws” so that members had the freedom to discuss any topic without regard to the strict regimen of Greek and Latin readings that formed the curriculum at early America’s colleges. As many as twelve of the first fifty members were Masons, and it is possible they borrowed the idea for a handclasp, sign, and other rituals from the Masonic order. The group named itself to outsiders only by the initials SP and more often ΦβΚ, and they soon became know as Phi Beta Kappa, the first Greek letter fraternity.

On March 1, Phi Beta Kappa conducted its third meeting and adopted twenty-seven bylaws. To uphold the group’s serious purpose, the rules required “that four members be selected to perform at each session, two of whom in matters of argumentation and the others in apposite composition.” In other words, two would present written arguments and two others would debate an issue. Worthy compositions were to be preserved. None has been discovered, but the topics noted in the minutes included the kind of debates that shaped the Republic:

The Justice of African Slavery; Whether a wise State hath any interest nearer at Heart than the Education of the Youth; Whether anything is more dangerous to Civil Liberty in a free State than a standing army in time of Peace; and Whether any form of Government is more favorable to public virtue than a Commonwealth.

The early brothers, determined to maintain their ideals, enacted bylaws that included a five-shilling fine for missing a meeting without an acceptable excuse, and said “That the least appearance of intoxication or disorder of any member by liquor, at a session, subjects him to the penalty of

ten shillings.”

In May 1779,

It being suggested that it might tend to promote the designs of this Institution, and redound to the honor and advantage thereof at the same time, that others more remoter or distant will be attached thereto, Resolved, that leave be given to prepare the form or Ordinance of a Charter party . . . with delegated power in the plan and principles therein laid down, to constitute establish and initiate a fraternity correspondent to this . . .

The charter party, from the French charte partie, or divided charter, is an agreement written in duplicate on the same sheet of paper and torn in two, one part kept by the originating chapter, the other going to the new branch. Phi Beta Kappa now had a means to expand.

The first charters were for chapters in Virginia. The William and Mary society as the originator would be the Alpha chapter and the others would be designated Beta, Gamma, Delta, and so on. Nothing came of the plan to create other Virginia chapters, but Hardy suggested extending the fraternity to other states, and the perfect courier was at hand.

Elisha Parmele had studied at Yale until the American Revolution forced it to close. He graduated from Harvard and came south for his health. He met Short, now chapter president, who introduced him to the society. Parmele was initiated on July 31, 1779, and by December’s anniversary meeting, he had been granted a charter for Harvard. Four days later, Parmele had a charter for Yale as well.

Parmele returned north, reaching New Haven in the spring of 1780. There he established Alpha of Connecticut by initiating four members. Parmele traveled to Cambridge in the summer of 1781 and introduced Phi Beta Kappa to four rising seniors, who were initiated that summer and began meeting in September 1781 as Alpha of Massachusetts.

The establishment of outposts in New England ensured Phi Beta Kappa’s survival. In 1787, the Harvard and Yale branches considered granting a charter to Dartmouth College in New Hampshire. They tried to consult with the William and Mary chapter but received no reply, and so they issued the charter together.

The founding chapter no longer existed.

In December 1780 Benedict Arnold led a British invasion of Virginia. The College of William and Mary suspended classes in January, and on January 6, 1781, Phi Beta Kappa president Short called a meeting “for the Purpose of Securing the Papers of the Society during the Confusion of the Times and the present Dissolution which threatens the University.” The members gave them to the college steward for safekeeping. The war had already scattered chapter members, and though William and Mary classes resumed the following year, Phi Beta Kappa did not. More than seventy years would pass before the Alpha of Virginia Chapter would be re-formed.

In 1783, Landon Cabell, one of the last members of the founding society, retrieved the papers from the steward. No one knew what had become of these documents until 1848, when Dr. Robert Cabell, Landon’s son, presented the minutes to the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond. In 1895, the minutes were returned to the College of William and Mary, where they reside in the Earl Gregg Swem Library.

After the William and Mary chapter disappeared, the debates and secrecy disappeared from the New England chapters. During the last years of the eighteenth and first years of the nineteenth century, secret societies came under attack from religious leaders who saw in them the advancement of philosophy over faith. In response, the cloak of secrecy was eventually lifted from Phi Beta Kappa’s proceedings. The regular debates that had been so important to the founders began to disappear from the New England chapters. By the 1820s, Phi Beta Kappa had essentially become an honor society with scholarship and academic achievement as the requirements for election.

In 1851, two William and Mary professors, Phi Beta Kappas from Union College in New York, sought to revive the Alpha of Virginia Chapter. They wrote to Short, then ninety-one, and with his approval, they re-formed the chapter.

Ten years later, another war swept over Williamsburg, and the college again closed, in May of 1861. The Civil War took a toll on the college. Union troops burned the Wren Building, gutted the Brafferton, and left the campus in ruins. Phi Beta Kappa tried to come back after the war, and in 1875 six new members were initiated, but there were no further meetings until 1893, when the chapter was again reactivated.

Today, Alpha of Virginia is the proud founding chapter of the 280 branches of the preeminent honor society in America.

Phi Beta Kappa’s roster reads like a who’s who in American political life, the arts, and business. Seventeen presidents of the United States were members, including John Quincy Adams, Theodore and Franklin Roosevelt, Woodrow Wilson, Dwight Eisenhower, Jimmy Carter, George H. W. Bush, and Bill Clinton. Ten chief justices of the Supreme Court, including William and Mary’s John Marshall and current Chief Justice John Roberts, were Phi Beta Kappas, as well as 136 Nobel laureates.

Leonard Bernstein, Pearl Buck, Glenn Close, Francis Ford Coppola, Betty Friedan, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Gloria Steinem, Paul Robeson, and Booker T. Washington all were elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

So was John D. Rockefeller Jr., son of America’s wealthiest man and an initiate of Brown University in 1897. So was the Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, rector of Williamsburg’s Bruton Parish Church, who was given a gold Phi Beta Kappa key on the 130th anniversary of the society’s founding. Their Phi Beta Kappa associations proved pivotal to Williamsburg’s restoration.

In 1924 Rockefeller, a Phi Beta Kappa senator—the senate being the national governing body—attended a banquet in New York focused on raising funds for a proposed Phi Beta Kappa national memorial hall at William and Mary. Goodwin addressed the gathering on “The College of William and Mary and Its Historic Environment.” Since 1923, he had been teaching religion at the college and raising funds for campus improvements, which included restoration of the Wren Building. Who better to fund the plans than Rockefeller?

Goodwin met Rockefeller that evening and invited him to visit Williamsburg. Rockefeller said he would like to visit some day. Goodwin took him at his word. During the next two years, Goodwin wrote letters renewing his invitation. In the interim, Goodwin’s ideas grew to include restoration of some of Williamsburg’s eighteenth-century homes that he thought the college should acquire for faculty housing and academic uses. He helped save a 1700s house about to be demolished for a gasoline station, began restoration of the church-owned Wythe House, and forestalled development of properties adjacent to the 1714 Powder Horn.

In March 1926, Rockefeller combined a house-hunting trip, a visit to Hampton Institute, which he had supported for years, and an excursion to Williamsburg, perhaps to inspect the progress on the new Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall now being built through his fund-raising efforts and donations.

Goodwin provided a tour of the college and expanded it to include historic sites throughout the city. In November, Rockefeller returned for the dedication of Phi Beta Kappa Memorial Hall—reduced by a 1954 fire to a wing of Ewell Hall. At the dinner that evening, Goodwin sat next to Rockefeller, and they talked about not only restoration of the Wren but reconstruction of the Capitol and the Raleigh, and of acquisitions all over town for the benefit of the college. Rockefeller authorized Goodwin to have sketches drawn. In 1927, Rockefeller undertook to restore the town.

Phi Beta Kappa was born in the Raleigh Tavern, created by young men with a vision. The society that grew from their vision would honor the most accomplished students in America and play a role in Colonial Williamsburg’s creation. In 1932, Virginia’s governor, city fathers, restoration officials, and a few Phi Beta Kappa keyholders gathered on Duke of Gloucester street for the dedication of the town’s first restored exhibition building, the Raleigh Tavern.

Writer and producer Michael Lombardi contributed to the autumn 2007 journal “In Search of the Frenchman’s Map,” a story about the 1780s plat of Williamsburg that guided the city’s restoration.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Richard Nelson Current, Phi Beta Kappa in American Life: The First Two Hundred Years (New York, 1990).

- Janice Fivehouse, “The History of the Alpha Chapter of Phi Beta Kappa” (master’s thesis), 1968, Earl Gregg Swem Library, Williamsburg, VA.

- “Minutes of the Alpha Chapter of Virginia, Phi Beta Kappa; December 5, 1776 to January 6, 1781,” Earl Gregg Swem Library, Williamsburg, VA.

- The Original Phi Beta Kappa Records, including the minutes of the Meetings from December 5, 1776, to January 6, 1781, at the College of William and Mary, with notes and introduction by Oscar M. Voorhees (New York, 1919).

- Jane Carson, James Innes and His Brothers of the F.H.C, Williamsburg Research Studies, Colonial Williamsburg (Charlottesville, VA, 1965).

- William and Mary website: http://wm.edu/about/history/index.php

- Phi Beta Kappa website: https://www.pbk.org