Online Extras

Extra Image

Library of Congress

A mocking funeral for the Stamp Act. Colonists resisted taxes Britain levied to pay for its wars, even ones protecting the colonies.

Library of Congress

England’s rivals haggle over dividing its empire while, bottom, ministers at home quarrel and George III weeps in back.

The expense of the French and Indian War pushed England to raise more revenue from the colonies, which meant new taxes.

Dodging the Check

by Andrew G. Gardner

A fifteenth-century Italian military expert, Marshall Trivulzio, advised France's Louis XII that "to carry out war, three things are necessary: money, money, and yet more money." More than five centuries later, the advice is as valid. The Iraq adventure cost United States taxpayers more than $770 billion. Afghanistan? About $372 billion and counting. Vietnam? In today's dollars, $686 billion and the lives of 58,000 brave service members. The list goes on. Throughout the ages, the cost of waging war—the sacrifice of national blood and treasure—has always been heavy. So it was for Great Britain throughout the eighteenth century, as it and its long-time enemy France, struggled for global dominance. Prevailing in this strategic battle, the theory went, would ensure the security of the winner's colonies. More colonies meant more trade; more trade translated into increased wealth for the mother country. Funding the fighting was seen as an investment.

Between 1756 and 1763, for the third time in little more than half a century, France and Great Britain were again at war. Campaigns were fought around the globe. At stake was the fate, primarily, of the British and French North American empires, but the rich sugar-producing islands of the Caribbean as well. Half a world away the rivals wrestled for control of the Indian subcontinent, and when Spain threw in with France in 1761, the fight spread to Cuba and the Philippines. Winston Churchill would call it the First Great World War.

In Europe, the British army and its Prussian allies tied down 90,000 French forces to prevent the French from pouring more troops across the Atlantic into Canada and the Caribbean. In North America, the French and Indian War was a bloody, guerrilla-type contest unlike anything Britain's highly trained troops had experienced. It began dreadfully, before hostilities had even been declared. The forces of arrogant British General Edward Braddock, with young George Washington his aide de camp, were decimated at Fort Duquesne—now Pittsburgh—in 1755. British historian Corelli Barnett wrote, "It was not the best beginnings to a great war for World Empire."

Four years later, France's designs for a transatlantic empire effectively expired with the heroics of General James Wolfe's forces on the Plains of Abraham before Quebec. As the smoke cleared and Britain and France sat at the peace table in Paris in 1763, it was obvious that Britain's investment in a war of aggressive imperial expansion had paid dividends. Save for two tiny islands off Newfoundland, France was forced from North America. Britain mopped up the spoils . . . Canada, Louisiana from the Mississippi to the Appalachians, Florida, and the Caribbean islands. Now all it had to do was work out how to pay the bill.

The Roman philosopher Cicero is credited with the maxim that "monies are the sinews of war." That truth was clear to London in 1763: Britain's body politic was stretched to breaking point. Seven years of fighting had made the country's books uncomfortable reading. The figures dripped red over every page. For seven years, military expenditure had consumed 14 percent of Britain's national income.

Put in perspective, since 2001 the United States has spent $1.1 trillion, or about 7 percent of one year's gross domestic product, on wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The Seven Years War, as the French and Indian War is more widely known, with 100,000 British soldiers in the field—more than 20,000 of whom saw service in America—and 75,000 seamen serving in the Royal Navy meant the government went deep into debt to advance the struggle. Three out of every four dollars spent by the British Government directly helped secure a military victory, while borrowing from Dutch and British bankers drove the national debt from £75 million to £133 million. In today's world, used to near trillion-dollar annual deficits, the figures seem tame, but for the time they were extraordinary. The interest alone on the loans took 40 percent of Britain's tax revenue. The situation was unsustainable, and if left unaddressed, Great Britain faced defaulting on its bills, in effect, becoming bankrupt.

That's when the trouble started, giving rise to the story every American knows: the attempt by the British to have their American colonies share the financial burden created by the French and Indian War. The means was to be increased taxation. As everybody is aware, the plan did not quite work out. Two-and-a-half centuries on, it is challenging to revisit the question why.

How about: No taxation without representation. Was it that simple? Was taxation the sole irritant that brought about a fratricidal conflict of such magnitude? Or was there something else? Had the war and the huge cost borne by Britain not been fought to bring Indian raids on the American frontier—encouraged by the French—to an end? Had the victory not ensured freedom from the threat of Catholic French rule that drove terror into colonial hearts? Judging from a Virginia preacher's sermon in 1758, things had not been pretty. The Reverend Samuel Davies asked:

Need I inform you . . . what barbarities and depredations a mongrel race of Indian savages and French Papists have perpetrated upon our frontiers? How many deserted or demolished houses and plantations? . . . Some lie dead, mangled with savage wounds, consumed to ashes with outrageous flames, or torn and devoured by the beasts of the wilderness, while their bones lie whitening in the sun. . . . Our frontiers have been drenched with the blood of our fellow subjects, through the length of a thousand miles; and new wounds are still opening.

But soon after the Peace of Paris, there was uproar. England proposed that the colonists provide $60,000 to cover a share of the $200,000 required to maintain a standing army to police the frontier. So, had the fear that the colonists felt for their survival evaporated? It seems unlikely, since Pontiac's Indian war was raging and the French were still on the west bank of the Mississippi. What went wrong?

To an outsider, a one-third colonist and two-thirds Great Britain split of the costs appears reasonable, even though it did involve the dreaded "T" word. At the time, taxes in Britain amounted to a punitive 26 shillings per head per annum. There were taxes on land, on houses—based on the number of windows—offices, carriages, newspapers, spirits, tobacco, and beer, to name but a few. When in 1763 the authorities slapped a tax on cider, there were riots. By comparison, in colonial America taxation per capita has been estimated at one shilling per annum, hardly "crushingly oppressive," in the rhetoric of the day. So when the 1764 Sugar Act and the Stamp Act of 1765 were introduced, were the colonists making excuses to dodge the check?

Despite the underappreciated fact that at the time only 3 percent of British men—214,000 out of eight million—had a vote in parliamentary elections, mainland Britain had a civil administration that had honed to a fine art the science of extracting every taxable pound from every citizen. Not true of the colonies.

Though customs duties had been in place in America for years, the inefficiency of a corrupt customs service run from Britain by less-than-zealous landed gentry raised little money for the crown. It beggars belief, but revenue from American customs was only £1,800 sterling a year. Smuggling of molasses from the French West Indies was rife, and colonists were cheerfully used to raising glasses of duty-free rum.

When the British Prime Minister George Grenville instigated a crackdown with the American Duties Act of 1764, colonists fumed. There were new incentives for Royal Navy ships and customs officials to apprehend smugglers. Warrants called "writs of assistance," which empowered customs officers to conduct general searches, raised howls of protest. Worse, a vice-admiralty court was set up in Halifax, Nova Scotia, where smugglers faced a royally appointed judge sitting alone, unrestrained by the peskiness of a jury or common law. Guilty verdicts and stiff sentences here were more likely than in local courts of friendly magistrates and juries of a smuggler's peers.

By the mid-1760s, customs officials were earning their keep, collecting £30,000 pounds a year. The distillers and merchants of New England were particularly hard hit. Bostonian John Hancock of Declaration of Independence signature fame had made his fortune smuggling French molasses. He, like many of his peers, had little love for Grenville or his successors.

Add the effects of the Stamp Act of 1765, which taxed most everything in sight, and the picture is clear. The British were hitting the middle and merchant classes hard, where they had never been hurt before . . . in their wallets. And yet, Peter Thomas, a Welsh historian, points out:

Great care had been taken to make the Stamp Act acceptable to the colonies. The total tax was small. The wide range of duties . . . averaged only about 70 percent of their equivalent in Britain. All money raised by this tax and the 1764 molasses duty would be handed over to army paymasters in the colonies. There never was any foundation for the contemporary and historical myth that Britain would drain money from America.

Nevertheless, the political rhetoric of the time was fearsome. The talk was of liberty and freedom, oppression and slavery—bywords of the founding narrative of America. Outsiders still shake their heads, not least because of the inherent irony that the American economic engine of the era ran on African slaves who would taste neither liberty nor freedom for another century.

Grenville's Stamp Act crossed a line. The argument about direct versus indirect taxation, and direct representation, takes up books of history. Yet viewed from afar, two hundred and fifty years down the road, it seems disingenuous to argue that, had the colonists been directly represented in the British Parliament adopting such taxes, everything would have been hunky dory. Some historians have suggested it was not so much "No taxation without representation" as it was a case of "No Taxation . . . period."

This takes us back to the question: Was there something more than just an aversion to paying taxes? What really made the colonists dig in their heels and say enough is enough?

There are plenty of candidates: the first draft of Prime Minister Grenville's Quartering Act decreed that the colonial authorities were on the hook for providing food and lodging, including beer and cider, for frontier forces. The 1764 Currency Act followed, declaring an end to provincially minted money in the nine colonies south of New England. Aimed at controlling inflation, it was seen in America as beneficial only to English merchants. Nevertheless, several colonial grandees, particularly in Virginia, had become rich in currency exchanges involving colonial notes. When they saw the game was up, not surprisingly they cried foul. The banning of these local currencies also ushered in a vicious credit crunch and recession that affected everyone. The British, particularly London's tobacco merchants, were seen as the culprits. Thomas Jefferson said that highly indebted planters could only break free of their indebtedness by handing their liabilities on to the next generation, and as such were little more than "a species of property annexed to certain mercantile houses in London."

George Washington knew what Jefferson was talking about. Having retired as colonel of the Virginia Regiment in 1758, he led a planter's life that was as problematic as Jefferson's. Like many of the landed gentry, Washington lived beyond his means, constantly in debt to London merchants. For the well connected, land speculation was a way of keeping the wolf from the door. To this end, Washington had invested with other Virginia worthies to secure a grant of 200,000 acres in the Ohio country. No doubt, it helped that Robert Dinwiddie, a former Virginia governor, was a fellow investor. But after the 1763 Peace of Paris, the British Government, with the stroke of a pen, changed the playing field. In response to Indian chief Pontiac's war, England's Proclamation of 1763 decreed that all land west of a line along the crest of the Appalachians to the Mississippi an Indian reserve, off-limits to Anglo Americans. Settlers west of the line were to decamp and head back east. The standing army the British wanted the colonists to pay for was to stop white settlers heading west into the newly created Indian reserve.

Britain saw the proclamation line as a way of defusing frontier tensions, ending the expenses of Indian wars, and concentrating settlers on the seaboard to participate in the mercantile system. Washington and his associates, as well as the seventy thousand Anglo Americans who had put their lives on the line against the French in the colonial militia or with the British Army, saw it as a slap. If ever there was an issue ready-made for colonists inclined to turn their backs on British rule and seek an excuse for dodging the check, this was it. It affected everybody. France was a spent force, the Anglo American population had increased fivefold in the previous fifty years, and immigrants were arriving by the shipload from Europe, looking to settle in the continent's vast hinterlands. The proclamation line intended to stop that.

The Proclamation of 1763 gets less attention in popular history than taxation without representation. Mention it in company, and you may get blank stares. The effects of the Declaratory Act, the Townshend Revenue Act, the Intolerable Acts, the tea tax, the Boston Port Act, and the rest are easier to quantify than those of the line, yet the Proclamation of 1763 got as many colonists' backs up, and colored events for the next fifteen years.

The duc de Choiseul, France's foreign minister, had brushed off the loss of his nation's North American empire with a wave of the hand and predicted that without the fear of French forces on the frontier, Anglo Americans would soon cast off the British yoke and go their own way. He was right.

Andrew Gardner, who writes on Canada’s Salt Spring Island, contributed to the autumn 2010 journal the article “Mumbo Jumbo Meets Its Match.”

Extra Image

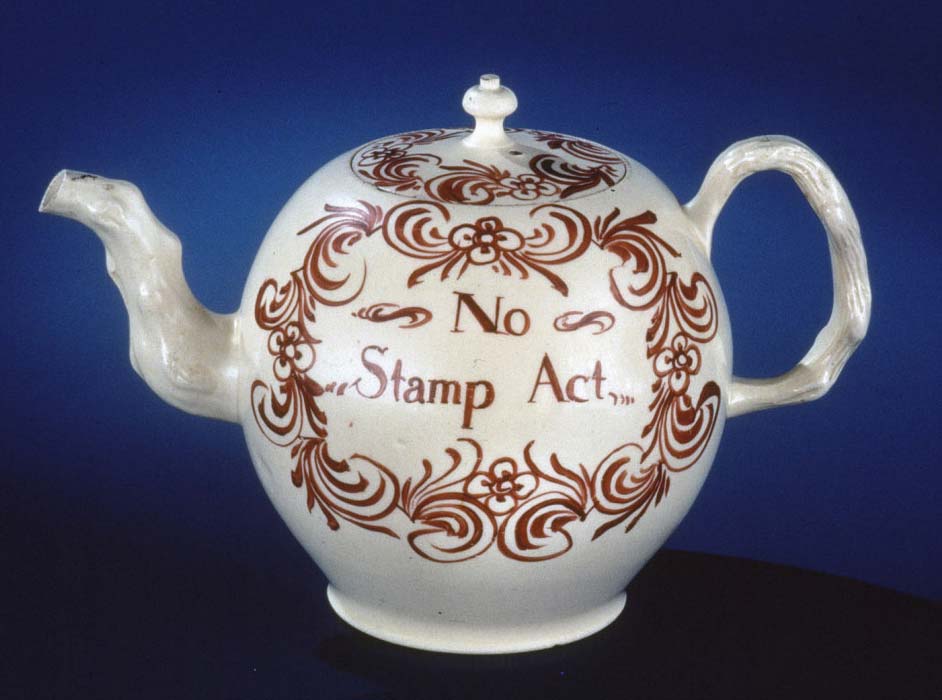

The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

A creamware teapot commemorates the repeal of the 1765 Stamp Act, circa 1766.