Online Extras

Zodiac Slideshow

If the time of year and the time of night were propitious, buried treasure awaited diligent searchers—here, interpreters Richard Davis, left, and Nat Lasley, with a dowsing rod—a conviction shared by hundreds if not thousands of colonial treasure hunters.

The recipe for riches required the sprinkling of magic potions, incantation of the appropriate spells, and then a period of silence to keep the genies of treasure from sinking it deeper into the earth. Yet, despite persistent attempts, magic never led to moolah.

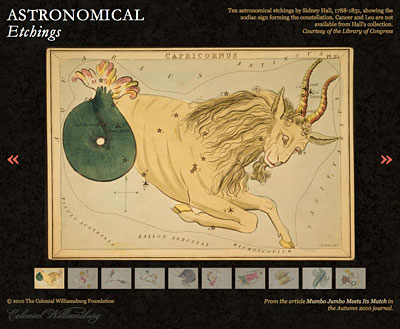

Scorpio was but one of the Zodiac signs parsed by the astrologers colonists consulted in the eighteenth century.

Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University

Devotees of the occult indulged in reading tea leaves or, in the print above, coffee grounds to determine fate and fortune.

Mumbo Jumbo Meets its Match

by Andrew G. Gardner

Benjamin Franklin and a friend ventured out on a summer 1729 afternoon stroll from Philadelphia. Half a mile from town, they came on an array of large pits in the ground, recently dug. The holes were the workings of the treasure seekers— ordinary folks caught up in a fantastical obsession that persisted more than a century. They believed the countryside abounded in buried treasure chests waiting to be discovered.

The idea was a blend of folklore, hocus-pocus, and wishful thinking. In New Hampshire the treasure had belonged to Captain Kidd the pirate and could be found even miles from any seacoast. Of course it never was. In Ohio, 1,000 miles from the ocean, Spanish and Indian gold was the lure. In Pittston, Maine, pits were dug eighty feet deep, and in Vermont a pockmarked landscape showed “where generation upon generation of money diggers have worked their superstitious energies.” Some used talismanic seer stones to find the underground money caches; others divining rods and such like.

The whole nonsensical enterprise must rank as one of the greatest examples of a gullible population deluded en masse. Had Franklin, an exceptional natural philosopher and one of America’s foremost scientific minds, returned to the diggings after dark, he might have remarked the insanity of a search shrouded in magic, ritual, and superstition. The best time to dig, according to the diggers, was between midnight and dawn. Summer was the best season because the heat from the sun caused the treasure to rise nearer the surface. With a silver spoon, they spread magic potions around the search site to expel evil spirits and recited ritual incantations from astrological texts. Thereafter, the rule of silence prevailed. Any talking would cause the treasure to bury itself further into the ground or set the spirits guarding the loot to get angry, with who-knew-what consequences. How could rational men and women believe in such fantasies?

Echoes of such notions, however, persist in a popular culture that pays to see Hollywood’s cave-raiding archaeologists and big-time scientists caught up in Holy Grail murder mysteries. Franklin, founder of the American Philosophical Society and one of early America’s greatest enlightened minds, has his name taken in vain by a fictional character in the 2004 film National Treasure. Played by Nicholas Cage, Benjamin Franklin Gates, a sixth generation seeker, looks for treasure of the founding fathers.

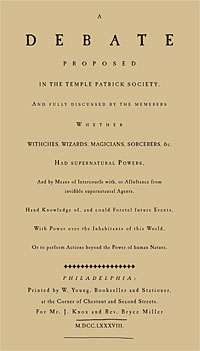

Trying to make sense of the twists and turns of some of our ancestors’ antics has never been easy, and when it comes to interpreting how colonists of centuries ago saw the world, it is more so. What we can divine is a pattern where superstition, astrology, and the occult ruled the early American roost without apology. The extent to which the colonists’ lives were influenced by what we consider irrational and just plain silly is staggering—witness the treasure seekers. But it went further: their lives were informed by a firm belief in evil forces that stalked them daily. The devil, witches, and magic were, in some colonists’ minds, real and terrifying. Poor hunting or fishing could be put down to a magic spell cast by a malicious neighbor. Prodigies—anything strange and out of the ordinary in the natural world, from earthquakes, meteorites, and thunderbolts to oddly shaped root vegetables— would have people quaking with the expectation that the day of judgment was nigh. Charms and amulets were credited with keeping the devil at bay. Horseshoes nailed to our twenty-first-century suburban doors are a hangover from those days. Witchcraft—including sticking pins in dolls that resembled the intended victims—was blamed for the sickness and death of loved ones and livestock. It was not something to be meddled with.

Today, many still give a cursory nod to newspaper horoscopes, but to most their wisdom and insight are short of earthshattering. We still might remember to turn the change over in our pockets at the sight of the new moon, a still-to-be-proven attempt to bump up our chances in the lottery. But if disease strikes us, it is doubtful we would rely on the musings and advice of an astrologer to specify the best dates to be bled, or which herbs would benefit which organs, bearing in mind the planetary influences of Venus, Neptune, or Mercury, or the added complication of whether the moon was in Aquarius, Pisces, or Gemini.

What changed the world forever began to appear in the Americas about the mid-seventeenth century. Western Europe’s philosophers and scientists tended the roots of the Enlightenment before it crossed the Atlantic, where, in time, such men as Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson seized on it. The philosophers and early scientists set in motion an upheaval that carried society from an era of “cunning men” and “wise women,” whose superstitious mumbo jumbo had held sway for centuries, into the Age of Reason. Human reason, it was seen, could defeat ignorance, ritual, and superstition. A trust in emerging sciences solved problems that plagued humankind and helped establish a degree of control over the natural world. But it was not all plain sailing.

The church that had held sway over the lives of men for so long was not always sympathetic to a view of the world based on observation, experimentation, and logic, as opposed to faith. With a pedigree of fighting Satan and the powers of darkness, as well as a monopoly on delivering salvation, the church saw itself as the only true religion, and was not about to meekly concede its position. Galileo’s epic and losing battle in 1630 against the Church of Rome began when he challenged its ancient dogma with science to demonstrate that the sun, not the earth, was the center of the planetary system. It was an early example of the struggles that lay ahead.

“In all Superstition” wrote Sir Francis Bacon in 1632, “Wise Men follow Fooles.” One such wise early American was Cotton Mather, a politically influential New England Puritan minister who is best remembered for his role in the Salem witch trials of 1692. But Mather is an example of someone who later in life began to consider the Enlightenment seriously, and to look objectively at what made the natural world tick. In his earlier years, Mather’s world revolved around all things spiritual.

He concluded that the devil’s influence was everywhere. He became a rabid witch-hunter. He pushed for spectral evidence—evidence from ghosts or demons—to be admitted during the Salem trials, where he dismissed one of the accused as “a rampant hag.” As for the result—the last witch execution in the English-speaking world—Mather concluded, “For Justice being so far executed among us, I shall Rejoyce that God is Glorified.”

But the other, intriguing side to Mather’s character tended to the fledgling sciences that were beginning to raise a new generation’s interest. He experimented with the breeding of corn, attempting to document what would today fall in the realm of genetics. And during a 1721 smallpox outbreak in Boston, he took a courageous stand, encouraging inoculation to prevent the disease. Despite a public outcry that the procedure was tantamount to murder, Mather persuaded a doctor to try it on the doctor’s only son and two slaves. All survived.

Mather’s acceptance of this new scientific reality, unpolluted by a historical marinade of superstition, cannot have been easy, and highlights the sea change in thinking that seeped into the minds of the ignorant. In his earlier years, if challenged on his belief in prodigies, Mather resorted to name-calling; skeptics were dismissed as “not being gentlemen.” But as history professor Michael Winship writes, “Mather’s belief in prodigies was hardly idiosyncratic. People of all social ranks had long taken for granted prognostications of future events. Prodigies were part of a larger world of wonders, of omens . . . of magic and supernatural interventions.” Even though, for a man of the cloth who regularly spent his evenings peering at misshapen vegetables, attempting to divine the future, grasping the new science that clearly was at odds with his old, comfortable, yet strange and fanciful, ideas must have been some leap of faith.

Yet Mather’s generation was the first to have to ask whether its world and its long-held beliefs were right. In 1719, the northern lights unexpectedly lit up New England’s night skies. Some were fearful for their future. A Harvard associate of Mather’s said, “No man should fright himself by supposing that dreadful things will follow, such as Famine, Sword or Sickness.” But Mather was not quite convinced, and pursued his investigation of the aurora borealis with a suggestion that it was not unreasonable to suppose that angels were responsible. Yet, by 1726, two years before his death, Mather was in print telling people to ignore “Superstitious Fancies about eclipses or comets.” Perhaps he had come full circle.

The history of divination, or fortune telling, stretches into antiquity. Roman priests—the augurs—dissected dead animals and studied the arrangement of the internal organs to foretell events. Through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, astrology was the divination of choice for the American colonist. Astrological almanacs circulated widely in the colonies, the bestsellers of the age.

As conceived, astrology was a serious business, and as near rational as anything in the ancient world. Celestial machinations ran like clockwork, were readily observable, and could be measured and recorded. That led the ancients to attempt to correlate day-to-day happenings on our planet to what was happening in the heavens. But by the time the colonists arrived in America, astrology, despite an interest shown by such astronomers as Isaac Newton, had a surfeit of mumbo jumbo, which, counter-intuitively, made it popular. Astrology presented a perfect tool for melding that art with sorcery and witchcraft into a sort of cure-all, alternative pagan religion that found an audience, particularly among rural colonists.

Throughout the colonies, occult religion was common. Private library lists from the era confirm the ownership of occult texts, often among ministers. Thomas Teakle of Accomack County, Virginia, was an Anglican priest around the end of the seventeenth century who had a collection of reading material that would not look out of place in a twenty-first-century New Age bookshop. Among scores of titles in his library, Teakle could open Medicina Practica: or Practical Physick to mug up on astrologically generated potions or alchemical recipes for turning lead into gold. Or he could consult a 1670 tome of bestselling magic by Marin de la Chambre titled The Art How to Know Men, which dealt with horoscopes as well as chiromancy and metoposcopy, the art of foretelling the future from the wrinkles on a subject’s forehead.

Occultists hung out shingles proclaiming their ability to find lost objects, and advising on best dates for setting out on a journey, starting a business, getting married, or getting pregnant. The same sorts of questions that people ask today’s fortune-tellers. But in colonial times, health was the issue that took most people on a visit to the astrologer. An individual’s horoscope, it was claimed, gave insights into how someone related to the greater powers of the universe. Today we look on this as a bit of fun, but back then, when average life expectancy was less than forty and the practice of medicine was not advanced, the cunning men and wise women had clients knocking down their doors.

As the seventeenth century became the eighteenth, ten out of twelve children died before their second birthday. That stark statistic from the time of the Enlightenment suggests why colonists placed their faith so completely in the gods and, for insurance, the charlatans who offered occult alternatives to prayer.

Medical science had been climbing up the learning curve throughout the 1600s, but spreading the new knowledge was slow. Physicians prescribed such compounds as ground-up Egyptian mummy powder, milled unicorn horn, and castoreum—one ingredient of which was a vile-smelling root popularly called devil’s dung—to be taken while reciting charms. For epilepsy, pulverized mistletoe was recommended, “as much as can be held on a sixpence coin, early in the morning, in black cherry juice, during several days around the full moon.” In 1634, a reputable English doctor prescribed for Governor Winthrop of Massachusetts a concoction of “live toads baked to black crisp.”

When sickness struck, as it so often did in colonial times, with a vengeance, there sometimes seemed little to choose between the certified doctor and a humbug. Cotton Mather at least seemed to realize that the state of doctoring drove colonists into the realm of the charlatans, who had “no natural efficacy for the cure of diseases.” In Mather’s book, the charlatans’ remedies were the cures of the devil. In time the advance of medical sciences—anatomy, physiology, and pathology, to name but three—would win out over the mumbo jumbo, or the devil, depending on your point of view, not entirely but enough to persuade the average citizen to think twice about whom to consult.

The Enlightenment began the trend that ushered in the Age of Reason, exposing human ignorance and superstition for what they were. It never succeeded, however, in banishing the darkness completely. Treasure seekers roamed through part of the nineteenth century, ever hopeful, but seldom rewarded. Today fortune-tellers of every shade ply their trade, convinced of their objectivity. Horoscopes market mumbo jumbo for the masses. Goes to show how timeless William Shakespeare’s observations were. “Lord,” he wrote in Midsummer Night’s Dream, “What fools these mortals be.”

Andrew Gardner, who writes on Canada’s Salt Spring Island, contributed to the spring 2010 journal the article “The Indian War.”