Online Extras

The Indian War

John Smith’s, and Jamestown’s, encounters with Indians initiated centuries of North American red-white violence.

Mike Crow Jr., Kody Grant, and Shawn Michael Perry in a Colonial Williamsburg electronic field trip about a Shawnee peace delegation to Williamsburg.

The Indian War

by Andrew G. Gardner

Keeping straight the wars between Native Americans and the Europeans who came to settle among them tests the memory. There were, to name a few, the Taino, Aztec, and Powhatan Wars, the Pequot War, King Philip’s War, the Pueblo Revolt, Queen Anne’s War, the French and Indian War, the Tuscarora War, the Yamasee War, the Creek War, Pontiac’s Conspiracy, Lord Dunmore’s War, the First, Second, and Third Seminole Wars, the Black Hawk War, the Navajo Conflicts, the Ute Wars, the Modoc War, the Red River War, and the Nez Percé War. From the struggles against Columbus’s depredations to the indigenous Brazilians fighting today for their hunting grounds, the roll of death and destruction unwinds across time and the hemisphere. James Loewen, historian and sociologist, says, “In one sense there was just one Indian war. It started in 1492 and it’s still going on today, in some parts of the Amazon.”

Loewen is among the textbook authors who have examined what is taught in American schools and found that its treatment of the aggression against Native Americans sweeps under the historical carpet the shameful and barbaric. “Slavery” he writes in his book Lies My Teacher Told Me, “is now taken seriously in our histories; conquest is not.”

Historian and author Howard Zinn, whose viewpoint mirrors Loewen’s, says, “What we didn’t learn was the fact that the American colonists that came here from the beginning were invading Indian soils and driving the Indians out of their land and committing massacres. The story that is not told in most American textbooks is the deceptions that were played on the Indians, the treaties that were made with them, the treaties that were then broken by the American government. It’s important to know that.”

Some people do. On an Indian reserve in Nevada, a young man sports a T-shirt with “Homeland Security” emblazoned above a picture of Geronimo and a group of his Apache warriors. The caption reads “Fighting Terrorism since 1492.”

Loewen says Europeans came to the New World with the Old World motivation of conquest, plain and simple. In the way that the Romans took over most of Europe two thousand years ago, and the Normans conquered Anglo-Saxon England in 1066, conquest was the primary incentive. “If you had to apply a one-word summary for what happened in North America,” Loewen says, “‘invasion’ would be that word. ‘Settlement’ is a euphemism. ‘Settling’ implies that North America had not already been settled, but it had.

“In our history we deny that the Indians had settled the continent thousands of years before . . . because it’s in our interests to deny it. The textbook that calls it ‘a virgin continent’ is pure nonsense.”

Hundreds of clans, tribes, or nations—call them what you will—were living here in the same way that European tribes and clans existed in Roman times. In North America, the Indians had trade routes that stretched from the Great Lakes south to the Gulf of Mexico and west to the Pacific. They had cultures, governments, and institutions the equal of some of what could be found in Europe at the time.

Nevertheless, on their arrival, the Europeans considered that they had found the New World, and by right of discovery could claim it as their own. Three hundred and more years later, in 1823, Chief Justice John Marshall of the Supreme Court of the United States, asked how the newcomers justified themselves, and answered:

On the discovery of this immense continent, the great nations of Europe were eager to appropriate to themselves so much of it as they could respectively acquire. Its vast extent offered an ample field to the ambition and enterprise of all; and the character and religion of its inhabitants afforded an apology for considering them as a people over whom the superior genius of Europe might claim an ascendancy. The potentates of the old world found no difficulty in convincing themselves that they made ample compensation to the inhabitants of the new, by bestowing on them civilization and Christianity, in exchange for unlimited independence.

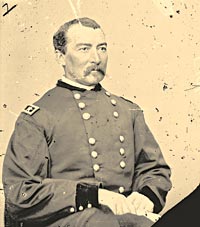

The Indians got European Christianity and civilization; the Europeans got the land. That explains the fighting. General Philip Sheridan, an Indian fighter, put it like this: “We took away their country and their means of support, and it was this, and against this they made war. Could anyone expect less?”

Sheridan, however, is better remembered for a colloquy he had with a Comanche chief participating in an 1869 Indian Territory conference. The chief described himself as a good Indian. Sheridan, smirking, said, “The only good Indians I ever saw were dead,” which time turned into “The only good Indian is a dead Indian.”

When Columbus came, there were perhaps 100 million Indians in the Americas and up to 30 million people in North America. In 1900, the Native American population in the United States amounted to about one million. Loewen says, “Disease, warfare, and the loss of their culture was responsible for the deaths of 90 to 95% of the Indian population.” Since the establishment of the Jamestown colony, the survivors of the North American Indian nations that once had the run of the continent have been squeezed onto little more than 2 percent of the American land base.

The conquest and wars were emboldened by racism. The Spanish conquistadores thought of the indigenous population as little more than animals to be exploited, and the English were hardly better. The Jamestown English regarded them as subhuman infidels and savages, some of whom were in direct communication with Satan. In the mid-seventeenth century, Francis Wyatt, Virginia’s English governor, said, “Our first work is the expulsion of the savages to gain the free range of the country for increase of cattle, swine etc. It is infinitely better to have no heathen among us, who at best were as thorns in our sides, than to be at peace and league with them.” George Washington said, “Indian’s and wolves are both beasts of prey, tho’ they differ in shape.”

Such demonization continued for three hundred years until the Indian Wars in the west were won and the whites triumphed. “As soon as it was in our interest to put down any other group, we put them down,” Loewen says. He calls it cognitive dissonance—“We’re fighting them and we need to think badly of them.”

During the French and Indian War, Virginia’s Reverend Mr. Samuel Davies persuaded his parishioners that the Indians were bloody barbarians who murdered children in their beds. “See Yonder!” he preached from his Hanover County pulpit, “the hairy scalps clotted with gore! The mangled limbs! Women ripped up! See the savages swilling their blood. These are not men nor beasts of prey. They must be infernal furies in human shape.”

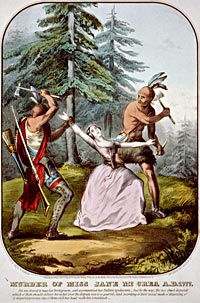

Ally such rhetoric to a painting in the Wadsworth Athenaeum depicting the scalping of a young white woman—Jane McCrea—in New York in 1777, at the hands of two Indian warriors. It would have been enough to make any prospective settler check his weapons. The pressure of new arrivals who headed for the frontier guaranteed the situation could only get worse. “But,” Loewen says, “it wasn’t just sheer numbers of settlers the Indians were up against; it was the power imbalance.”

The Indians could not compete with muskets, steel-tipped crossbows, gunpowder, armor, horses, and attack dogs. Consider the Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire in 1519. Under the command of Hernando Cortes, about 500 men-at-arms landed on Cozumel, just off the Mexican coast. Apart from their swords and pikes, Cortes’s force carried thirteen muskets, thirty-two crossbows, four small cannon, and some bronze guns. Within two years, Cortes and his men, with the help of native allies, brought the Aztec nation of hundreds of thousands to its knees in an orgy of terrorism, duplicity, and brutality.

In North America, the French controlled the fur-bearing arc of country from Cape Breton, west along the Gulf of St. Lawrence, across the Great Lakes, and south through the Mississippi Valley to the Gulf of Mexico. In the east, the English colonies, together with the Spanish in the south, completed the loop that hemmed in the unexplored area east of the Mississippi and its Indian nations. Attempting to defend their territories from white pioneers, the Indians had learned it was suicidal to engage the Europeans in direct military conflict. But laying down their arms and relying on the promised protection of a single colonial master had also been a bitter road to ruin. Instead, as the struggle for the control of North America between the French and the English boiled into the French and Indian War, Indian tribes leveraged what power they had, throwing in their lot with one side or the other.

September 13, 1759, on the Plains of Abraham at Quebec, General James Wolfe defeated the French. Britain, with the help of its Indian allies, was ascendant. At the Peace of Paris in 1763, France signed away her New World possessions save for two tiny islands off Newfoundland—St. Pierre and Miquelon.

The biggest change in Indian “fortunes came when Native Americans stopped being useful,” Loewen says, “and they had done a good job of playing the French against the English, maintaining a balance of power as long as they could. But all that ended with the outcome of the French and Indian War. It signaled doom for Native Americans.”

Historian Daniel Richter writes, “With a few strokes of European pens, the structural framework upon which Indian politics had depended imploded. The ring of competing imperial powers that had provided an odd security to the Indian country it surrounded suddenly collapsed.”

In 1763, the British issued a royal proclamation forbidding the English colonists from settling west of the Appalachians. The crown would have monopoly on land purchases from the Indian nations. To many colonists who had staked claims to this now-forbidden Indian reserve, including Washington, the proclamation was like a red rag to the bull—and in Loewen’s view was the biggest factor in pushing the settlers toward revolution.

The lot of Native Americans changed for the worse with the founding of the United States. In The Conquest of America, historian Hans Koning writes that “George Washington became known in Indian country as ‘the town destroyer,’ having ordered the obliteration of settlements of Mohawk, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca.” As the years progressed from the eighteenth to the nineteenth century, and immigration from Europe shifted into high gear, the carnage intensified.

According to Loewen, the War of 1812 marked the end of North America’s Indian Wars proper: “The rest was mopping-up operations.” President Andrew Jackson’s 1830 Indian Removal Act forced Indians remaining east of the Mississippi to move west, in some cases leaving their ancestral lands to be distributed to whites in a lottery. As the United States expanded westward, the destruction of the Plains Indians, the Northwest Indians, the California Coast Indians . . . the list goes on . . . followed.

Tactics varied—enslavement, starvation, terror—but the results were the same. Men, women, and children died by the thousands, and survivors force-marched to Indian reserves in what would become Oklahoma. There were many Trails of Tears. In Colorado’s 1864 massacre at Sand Creek—a peaceful, unarmed Cheyenne village—Colonel John Chivington ordered, “Kill them all, little and big, because nits make lice.” Ex-president Andrew Jackson said, “If you pursue a wolf, you have to kill the whelps too.”

December 29, 1890, at Wounded Knee, South Dakota, another massacre ended 300 years of North American Indian Wars. In a forced Indian removal, the United States Army, equipped with four rapid-fire Hotchkiss guns, mowed down 146 Lakota Sioux—men, women, and children.

Today we seldom hear about such engagements or discuss them. Loewen says that we should, as does Montana, where 6.5 percent of the population is Native American. The state requires Indian education for every child, “and other states are looking to follow Montana’s lead,” Loewen says.

“Despite the fact that every country tends to be ethnocentric about its own past and tends to emphasize that their country did things with the best of intentions . . . Indian history is an important antidote to the notion that European Americans are God’s chosen people. The idea that God is on our side began with the Pilgrims.”

He recalls a 1631 fight over land at Saugus, Massachusetts, when the Puritan minister Increase Mather said, “God ended the controversy by sending smallpox among the Indians.’”

“Now that is Manifest Destiny. Divine destiny,” Loewen says. “Same idea. God is on our side, fate is on our side, the overall sweep of history is on our side. Of course, it is a rationalization for what we do or what we did. If we killed them all, it was too bad, it was Manifest Destiny.

“However, history is not a film you can unreel. You cannot run it backwards. You cannot make native people independent again. Politically or logically, it is impossible. We can’t do a lot about injustices from whenever. But I do think there is a relationship between knowing the truth about the past, and justice in the present. Once enough Americans understand the truth about the past and what we did to the native population, they will be in favor of the next step, whatever that next step is.”

Andrew Gardner, who writes on Canada’s Salt Spring Island, contributed to the autumn 2009 journal an article about Captain John Smith’s departure from Virginia.