Online Extras

Sidebar:

Exploring the Coffeehouse

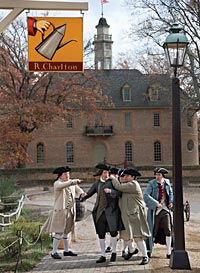

When George Mercer, Stamp Act agent, was roughly handled by irate citizens outside Charlton’s, Francis Fauquier, the lieutenant governor, stepped from the coffehouse porch to rescue him.

From left, interpreters Mark Sowell, Frank Megargee, Phil Shultz, and Jeffrey Villines, refreshed with coffee and tea, talk over news of the day at Charlton’s.

Williamsburg Again Has an R. Charlton’s Coffeehouse

A place to consider the roles of refreshment, debate, and ideas on the cusp of revolution

by Michael OlmertFor Imbibing Words as Much as Coffee

In 1773, James Boswell—the biographer of Dr. Samuel Johnson—visited the publishers of a London newspaper called the Public Advertiser. He was looking, he said, for a five-year-old back issue in which he had written an essay. The editors didn’t have a copy, but suggested he visit the Chapter House, a nearby coffeehouse. There, Boswell discovered not only his 1768 piece but bound volumes of newspapers, as well as an assortment of cranky and opinionated pamphlets and books.

That’s the thing about eighteenth-century coffeehouses: they were for imbibing words as much as coffee. The Chapter House, for instance, had a reading society that cost a shilling a year to join. The dues provided access to the house papers and books, for reading or quickly consulting to bolster an argument, presumably over coffee, though other stimulating drinks would also have been on offer, including tea and hot chocolate, wine and spirits.

Coffeehouses all over London—and about 2,000 of them operated in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries—were information centers and forums for discussion and debate, and sometimes for sedition. It is this last point that fixes the coffeehouse in the vortex of change engulfing not only the American colonies but much of Europe in the long eighteenth century.

That is why it is important for Colonial Williamsburg to have once again, after an absence of more than two centuries, a Charlton’s Coffeehouse reconstructed where it once was—if deductions based on a 1767 newspaper ad are right—at the east end of Duke of Gloucester Street. There can scarcely have been a better place for keeping one’s eyes on the prize. Out its sash windows and from its wide front porch, you could, and can still, witness comings and goings at the Capitol, the Secretary’s Office, and the outdoor Exchange—a place where merchants and planters did business. Law and justice, money and trade: they happened just on the verges of Charlton’s. And increasingly, during the run-up to the American Revolution, they were subjects of constant comment.

Pointedly, Lieutenant Governor Francis Fauquier reported that on October 30, 1765, he was accosted by an anti–Stamp Act mob while at “the Coffee house, in the porch of which I had seated my self with many of the Council and the Speaker who had posted himself between the Crowd and my self.”

Richard Charlton was a wigmaker, his wife a dressmaker. Sometime in the mid-1760s, the pair of them seem to have branched out of those trades a bit, taking possession of a 1750 store that stood on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street, at its far eastern end. It was a perfect location for attracting thirsty merchants and politicians leaving the Capitol or the Exchange. Right away, the Charltons improved the old utilitarian structure to make it a clean, well-lighted place.

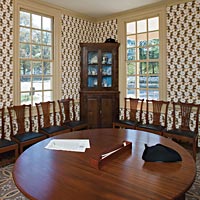

They created two main rooms side-by-side on the first floor, for two distinct classes of clientele. The first was a public room for the ordinary punters, a simply decorated space for people wanting a sensible place for refreshment and conviviality. Next to that, the Charltons created a more elite, more refined room, the sort of space that demands a carpet on the floor. This space was aimed at the governor and his council; it was also a space that could be rented for up-market functions.

The rooms are entered through two doors on the front of the building, though there is an internal doorway that provides access between the main rooms. But like all doors, it can be shut. Perhaps the real genius of the coffeehouse is its porch, an eight-foot-deep structure that runs the length of the building, thirty-five feet. A low-slope, cat-slide extension, the porch roof was useful for keeping the sun and rain off the drinkers, people from either room who sat on outdoor benches or who carried their chairs outside on fine days.

More important, the porch was an open, class-neutral space where social boundaries and margins could be tested. Here, ordinary people could be seen as perhaps not quite so common or loutish as the upper classes expected. And the elite and worthy need not be quite so aloof and self-satisfied as the lower classes presumed. That is to say, Charlton’s porch was the American experiment in little.

Which is why the porch was the perfect place for Fauquier’s rescue of George Mercer, arrived that day from England to sell the detested stamps to Virginians. In no other venue in town where ordinary citizens might see their lieutenant governor was he as vulnerable as on Charlton’s porch. Inside his Palace, in any of several rooms in the Capitol, or even in his coach, Fauquier was normally enveloped in a secure cloud of guards, servants, and secretaries. Moreover, the architectural setting in which he ordinarily appeared either physically limited access to his body or symbolically protected him with decorative flourishes that reinforced his connection to British power and might—the royal coat of arms, flags, displays of pikes and muskets, formal paneling and gated barriers. It was mainly the force of Fauquier’s personality that saved the day for both men—and that this porch confrontation happened in 1765, not 1775:

It was growing dark and I did not think it safe to leave Mr. Mercer behind me, so I again advanced to the Edge of the Steps, and said aloud I believed no man there would do me any harm, and turned to Mr. Mercer and told him if he would walk with me through the people I believed I could conduct him safe to my house, and we accordingly walked side by side through the thickest of the people who did not molest us.

The next day, Mercer resigned his Stamp Act commission and announced he was returning to Great Britain.

Coffeehouses were breeding grounds for dissent, places in which a few disaffected souls could wind up even a slightly sympathetic audience. May 27, 1773, the Maryland Gazette reports that a “very respectable body” of freemen of the city of Frederick met at a coffeehouse to dispute the results of an election. Formally declaring it to be “illegal, unconstitutional, and oppressive,” they sentenced the paper on which election proclamation was written to be taken to the gallows, hanged, coffined, and “buried face downwards, that by every ineffectual struggle it might descend still deeper into obscurity.” A procession of “at least one thousand people” accompanied the coffin to its final resting place.

In London, in 1663, shortly after coffee was introduced to England, the government decided that coffeehouses had to be licensed. In 1675, Charles II issued a proclamation intended to suppress coffeehouses. The grounds (indeed) were that they were resorts of libel and sedition. At Oxford, university officials tried to ban the sale of coffee on Sundays because of constant complaints about the “very fantastical letters, full of sedition” circulating among the coffeehouses, riling up students and professors alike.

As you might imagine, stimulating drink—a shift in the sorts of drink offered in coffeehouses that reflected market forces, as they say today—could assist the power of rhetoric. That is, a shop might start out specializing in coffee or tea or chocolate, but in time it is offering all three to attract as many clients as possible. The next step is to sell wine and spirits. In Britain, alcohol was common in coffeehouses. In 1714, Daniel Defoe said that Shrewsbury had “the most coffee-houses . . . I ever saw in any town, but when you come into them they are but alehouses, only they think the name of coffee-house gives a better air.”

The final step is to offer cooked meals. This is especially true in Williamsburg, which had taverns and ordinaries but never more than one coffeehouse at a time. Certainly Richard Charlton’s coffeehouse quickly undergoes this evolution. A few years after he opens, on June 25, 1767, Charlton puts an ad in the Virginia Gazette that, significantly, changes the title of his establishment from coffeehouse to tavern:

The Coffee-House in this city—being now opened by the subscriber as a TAVERN, he hereby acquaints all Gentlemen travellers, and others, who may please to favor him with their company, that they will meet with the best entertainment and other accommodations, such as he hopes will merit a continuance of their custom.

At Charlton’s, it’s mainly the name “Coffee-House” plus a few archaeological remains that suggest coffee was available: a stoneware coffeepot, a cup, and a kettle’s copper spout. But there are hundreds of remains associated with tea service and its more elevated rituals: tea bowls, slop bowls, strainers, teapots, and a tea stand. Bones in the trash midden behind the house and in the ravine beside it show that elite and complicated meals were also on the menu: venison, peacock, calves’ heads, lamb, and mutton. Thirty thousand such animal bones were found. This suggests substantial fare, not snacks to accompany the coffee. In addition, a great deal of alcohol was consumed, to judge from the 15,000 shards of wine bottles unearthed. Apparently, Charlton was determined not to limit his clientele by only appealing to a single niche market. Something for everyone was Charlton’s dish of tea.

The southwest room, the public room, has a welcoming drinks-serving bar in one corner and a fireplace with a simple surround and mantle: neat but not gaudy. The room is sheathed in yellow-pine random-width boards, painted tan and set horizontally. The beading of the boards seems at first decorative, but it is practical. The wide beading at every joint will hide the inevitable gaps as the wood dries and contracts; the boards will not contract horizontally, only vertically, across the grain. Nor do the grooves between boards match up with the grooves of the facing walls in the room’s corners. In a century often regarded as addicted to symmetry and balance, this seems about as downmarket as you can get.

In truth, wood sheathing is more durable than plaster. Moreover, to save money, Charlton may have retained this simple décor as a holdover from when the room was a store in the 1750s. There are historic sites where this sort of wall sheathing still exists, including the storeroom in the Market Square Tavern and in the Nicholson Store, both in Williamsburg, and at White’s Store in Virginia’s Isle of Wight County.

By contrast, in the southeast room, the elite chamber, the walls are plastered and covered with wallpaper. It was meant to appeal to a moneyed, powerful class, or to those who wanted to appear so. It was probably a less-frequented room, a zone of quiet confidence, with better furniture and better pictures on the walls, and a fine carpet. It was a setting fit for a governor and his council and their well-to-do colleagues, a place where handshakes and deals were made. And unmade.

There was always something improving and a little didactic about coffeehouses. Scientists from the Royal Society in London gathered for lectures at the Grecian Coffeehouse. And at the Chelsea Coffee House you could peruse seventeen glass cases around the room, displaying mice skeletons, a piece of Queen Catherine’s skin, and “a very curious young mermaid fish.” Today, cafes are in museums; then, museums were in cafes.

In Virginia, Charlton’s seems to have been the site of improving lectures and amazing demonstrations. Archaeology has found a set of human vertebrae, and a finger bone with copper wires and a pin attached, possibly from an exhibit or an articulated human skeleton used in lectures. And there were other activities at Charlton’s: archaeologists found seventeen crucibles with trace amounts of gold, silver, and copper on the site. Did Charlton rent space to an assayer?

There was a third large space at the back of the first floor. The Charltons could have rented it, either to a tenant or as another meeting venue. Two staircases lead from the back room to the second floor, a cramped half-story where the Charltons lived without children. Here, it seems his wigmaking business continued, to judge from the hair curlers and bone combs found in the trash midden. You can imagine the pair of them, working not far apart in the consistent north light of the two dormers that project from the rear of the roof. He, with his wigs and curlers; she, with her dresses and pins.

And then it all ended, somehow, in 1771. Charlton moved to a backstreet house in Williamsburg, where he again took in boarders. Charlton joined a wigmaking partnership, which went bust in 1776. He died in 1779. His building passed into other hands, but once Virginia moved its capital to Richmond in 1779, it never again operated as a coffeehouse.

A murky photo from about 1880 shows a greatly reduced Charlton’s, a rickety one-story hulk with a low-slope roof, barely surviving. In 1889, the former coffeehouse is demolished, and a large Victorian mansion rises in its place. The builders reused many of the coffeehouse’s bricks, timbers, studs, rafters, sash windows, and doors in the new house. Rediscovered and studied by Colonial Williamsburg architectural researchers, they permitted a fairly confident reconstruction of the original Charlton’s.

That was made possible by a $5 million gift from Deborah and Forrest E. Mars Jr. of Big Horn, Wyoming. The Mars family has been a prominent supporter of Colonial Williamsburg for twenty-five years. It made Charlton’s coffeehouse the first major reconstruction on Duke of Gloucester Street in fifty years. Because of their generosity, guests will once again sit in a crucible of the Revolution, sip a dish of tea or coffee, and consider again the old, complex debate about resistance, rebellion, and death.

In the end, Charlton’s Coffeehouse helps define what once it meant to be deeply interested in politics and governance, to be moral and philosophical, and to be concerned with the commonweal. The coffeehouse was a place to be thoughtful and human, publicly wrestling with notions of power and belief without any certainty of finding ironclad conclusions. It’s a good place to prepare for the complexities of history and of life itself.

Michael Olmert is Professor of the Practice in the English Department of the University of Maryland, a regular journal contributor, and author of the recently published Kitchens, Smokehouses, and Privies: Outbuildings and the Architecture of Daily Life in the Eighteenth-Century Mid-Atlantic.

Suggestions for further reading: