Library of Congress

The Battle of Williamsburg in 1862 left the town under occupation by Union forces for the duration of the war.

John Charles was a boy in the war.

Library of Congress

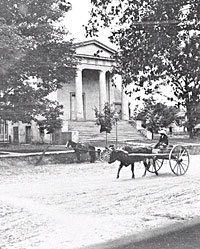

A Union wagon train with supplies for troops occupying Williamsburg on Duke of Gloucester Street, Bruton Church behind them

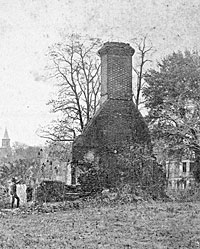

Union soldiers took bricks from remains of the Palace for construction elsewhere in town during the occupation.

The War

The Battle of Williamsburg in 1862

by Alexander Chesterfield

There is a story, probably apocryphal, that in the 1930s, as John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s eighteenth-century restoration of Williamsburg captured America's imagination, a newspaperman came to town and, in the course of an interview, pointed out to a local Virginia belle that the town's New York benefactor was a Yankee.

"Yes," she said, "but he's our Yankee."

So many years later, the anecdote is quaint. The epithet Yankee still sometimes is spoken in town—with tongue in cheek. Williamsburg has grown too big, too rapidly for Mason and Dixon Line distinctions much to matter anymore. And at Colonial Williamsburg, a museum leader in interpreting African American history and the tragedy of slavery, affection for the Lost Cause seems, shall we say, now beside the point.

Nevertheless, when President Franklin Roosevelt came in 1934 to praise the Rockefeller restoration and dedicate Duke of Gloucester Street, fewer than seven decades had passed since The War—and in Williamsburg there still was but one War. The lines of sympathy between Federals and Confederates yet were clearly drawn. Among the townspeople lived men who in 1862 had walked among the wounded from the Battle of Williamsburg and women who had nursed them.

Others were the children of men who had fought for southern independence, sons and daughters of such men as Captain John Francis Goodwin, who left Appomattox with Ulysses S. Grant's parole and shank's mared home to Richmond. He married Letitia Moore Rutherfoord, took a house down the street from Robert E. Lee's, and, in 1869, fathered William Archer Rutherfoord Goodwin. The boy grew up to be a minister, a popular speaker at Confederate veterans' reunions, and twice rector of Williamsburg's Bruton Church. In 1927, he persuaded Rockefeller to finance the city's revival.

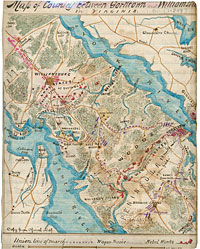

Confederate forces scrambled to defend Williamsburg in 1861, shoveling up a line of earthworks from Jamestown on the south toward Yorktown on the north to guard against the Union forces holding Fort Monroe at the tip of the Peninsula and cover the approaches to Richmond, the Rebel capital. The anchor of the city's defenses was Fort Magruder, about two miles in its front. Garrisoned by boys in butternut, Williamsburg became a Rebel base and depot.

Ten-year-old John S. Charles watched as the Confederates took possession of a lot and barn belonging to Dr. William Galt of the Eastern Lunatic Asylum, as it was called, and erected "therein additional stables and feed-rooms." Sixty-seven years later he wrote:

This was used to take care of the horses of soldiers who were absent from duty on account of sickness or other causes. The large number of horses kept there made it necessary to take them to the creek for water. This furnished great sport to many boys of the town (one of them was the writer) who were invited to take a horseback ride down to the College Landing, over a mile distant, three times daily for a long period. When this fine sport was broken up by the withdrawal of the Confederates in the spring of 1862, there was great lamentation among the boys of the town.

When Confederates burned Hampton to deny it to the Yankees at next-door Fort Monroe, sixteen-year-old Victoria Lee fled, with others, to Williamsburg. The city "at that time was overrun with refugees from the lower end of the Peninsula," she wrote in 1933. "Many of these unfortunate people were housed in the Main Building of the College, sometimes called the Wren Building, which was later used as a hospital."

Union General George McClellan began to push his army up the Peninsula in the spring of 1862. Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston, after delaying McClellan at Yorktown, ordered the southern troops to fall back toward Richmond. The Rebels paused at the Williamsburg earthworks to cover the withdrawal and met Yankee attacks May 4 and 5. Victoria Lee was at a house on Duke of Gloucester Street helping to "bake biscuits and fry meat for the Confederate army which was retreating before McClellan."

On the day that the Battle of Williamsburg was fought, I stood before this house all day passing out biscuits and meat to our men. Joseph E. Johnston, then in command of the Confederate army, passed as we were handing out food. He reined in his horse, waved in our direction, and shouted to the passing troops, "That's what we're fighting for boys."

As the last of the army was going by, an officer stopped his horse before me, and, handing me his sword, requested that I clean it and save it until he returned. I cleaned the sword—it was a very beautiful weapon—but its owner never came back to claim it.

This sword stood in its scabbard … in a corner of the hall for a long time. It was thrown away toward the end of the war by my Aunt Harriet, who was afraid the Yankees would find it, and charge her with aiding and abetting the Confederate cause.

Charles, who lived at the west end of town, watched the fighting on the afternoon of the fifth from a chair atop a three-story tower at the asylum. The beaten Confederates trooped down Duke of Gloucester Street, the Federals pursuing them through the city and beyond, its bands playing "Yankee Doodle" and "On to Richmond." They would nearly reach the Confederate capital before General Robert E. Lee repulsed them at Seven Pines, and drove them back on Williamsburg. Charles wrote:

McClellan's army followed close on the heels of Johnston's. It was one of the most magnificent sights I have ever seen—countless thousands of blue-clad troops, all in new uniforms. They were several days passing through Williamsburg. I saw part of this army when it returned from the vicinity of Richmond. It didn't look so splendid then… .

Just across the Stage Road, as the present Richmond Road was then called, was an old house, neat and attractive in appearance, known as Frog Pond Tavern, deriving its name from the fact that in front of it, and in the middle of the road, was a big mud hole, which seemed to defy all efforts to refill it; so there it remained practically all the year, and produced fine crops of frogs that furnished entertainment for the Tavern guests and to the neighbors during the summer months.

At the beginning of hostilities this Tavern was owned by an old gentleman, who was familiarly called "Old By Jucks." … He ran a store where both solid and liquid refreshments were served; and in connection with the store there was a large stable yard, where on court day and other occasions, the farmers' vehicles were put, and where their horses were fed. The store house stood a few yards west of the dwelling with steps on the outside leading to the lodging rooms above. Old By Jucks was a kind-hearted and genial old fellow, and tradition has it that on the morning of the most sorrowful day in old Williamsburg's history, May 6th, 1862, when McClellan's great army entered this city, Old Jucks, highly excited and greatly alarmed, as every one else was, went out in front of his house, from the porch of which hung a white flag; and with hat in hand made a polite bow to the advance guard of McClellan's vast army, and exclaimed, "Good morning, gentlemen, come in and have some hot biscuits and coffee."

Fort Magruder became the primary Union base in the area, and Williamsburg was uncomfortably occupied:

Some of the wounded Confederate soldiers were brought here and placed in private homes, as all the hospitals were filled. One young Confederate, mortally wounded, was taken to the Ware house, in which then lived old Mrs. Elizabeth Ware and her married daughter. This soldier boy died soon after reaching this house. He was tenderly cared for and placed in the parlor of this home awaiting disposition of the body. When General McClellan took possession of this city, the day after the battle, a guard was placed at every home where protection was requested. A Union soldier presented himself at the door of his house and, as instructed, asked if there were any sick or wounded soldiers there. When informed that there was a dead soldier there, he walked into the parlor and upon removing the sheet that covered the face of the corpse, the sorrowful fact was revealed that the live Union soldier was the brother of the dead Confederate lad; and as those kind-hearted southern women stood about the room, their eyes filled with tears for they knew the deceased was some Mother's darling and while they wept a tragic scene was enacted as the soldier in blue knelt by the bier and implanted a kiss on the brow of his dead brother, clad in Confederate gray. Soon an ambulance arrived, the corpse was placed therein and driven away—thus grimly demonstrating the truth of the expressions so often heard that this War was one of "Father against son, brother against brother."

The Baptist Church on Market Square, another refuge for the wounded, was the scene of more heartbreak. Victoria Lee said:

This building was used as a hospital, and at times I helped to care for the soldiers brought there. One morning, a few days after the Battle of Williamsburg, I entered the basement door of this building—I was carrying a pitcher of buttermilk to the sick soldiers—and, as I stepped through the doorway, one of the most horrible sights I have ever seen met my eyes—in a corner of the basement room was a pile of human arms and legs.

Charles wrote that the "defenders of southern rights, who died in this church, were buried in big square pits dug in the ground on the western side of the church… . Those heroes of the Lost Cause were, after the War, removed to Bruton Church yard, where a granite shaft now marks their resting place."

Opposite the Baptist Church stood the Colonial Hotel. Lee wrote:

The United States troops who were left in Williamsburg after McClellan passed through on the way to Richmond, used this building as a commissary. A large flag—a United States flag, of course—was placed on the front of this building, so that it hung out over the sidewalk; and the girls of Williamsburg, to avoid walking under it, used to walk out in the road. The United States troops, not to be outdone, however, got a long flag and stretched it completely across the Main Street.

Except for a day or two when rebel raiders like cavalry Lieutenant Colonel William P. Shingler of South Carolina dashed into town, Williamsburg remained a captured city, the College of William and Mary's Wren Building anchoring the boundary between Confederate and Union territory. The school stood at the apex of the intersection of the Stage Road and the Mill Road, today's Jamestown Road:

The College during the Civil War was used first by the Confederates, as a hospital, and storage space for quartermaster's supplies. After it fell into the hands of the Federals, it was used for a short time as a hospital to take care of both Union and Southern wounded. After the retreat of McClellan's Army, July, 1862, the College was abandoned and was destroyed by fire the following September.

In order to afford protection against frequent Confederate raids, the windows and doors of the College, opening to the north and westward were bricked up, with port holes in them for small arms. Deep ditches were dug from the north, east, and the southeast corners of the College, extending some distance beyond the "Stage Road," and the "Mill Road." In these ditches were placed vertically big logs ten feet long, and three feet in the ground. These logs were fitted with port holes so as to guard against Cavalry raids down the two roads. Some distance in the rear of the College and extending in a curved line far beyond the Mill and Stage roads was constructed an abatis consisting of tops of big oak and beech trees with sharpened limbs set in the ground, standing westward and all entangled with wire. These were there when the War ended.

Little of the Wren then remained, however. Union forces had destroyed most of it, and chunks of the rest of the city. Charles said residences were "pulled down by Federal soldiers and taken to Fort Magruder to furnish material for winter officer's quarters, etc." At the Henley Jones Farm, the

barn and its contents were destroyed by fire by Union soldiers on the same day that the College was burned. These soldiers were smarting under defeat by Col. Shingler's Cavalry and also fired by a liberal supply of 'The Rosy.' These were the same patriots who burned old William and Mary on that same day and then hilariously rejoiced over their heroic work.

All along Duke of Gloucester, there were reminders of war. Confederates used the Williamsburg Female Academy on the old Capitol site, and the Methodist Church on Duke of Gloucester, for hospitals. The Yankees made today's Palmer House their headquarters, and pressed the John Blair House into service, too:

The Federals finding that there was a brick bake oven on this property, took charge of it and greatly enlarged the capacity of the oven, which extended from the basement out into the back yard. Its oval top, covered with earth, was enjoyed by the children (not kids) of the neighborhood who romped up and down on it, much to their amusement. This shop, was operated by Federal soldiers, bakers, who daily made up and baked wagon loads of bread, which was hauled in army wagons each morning and evening down to Fort Magruder for the troops camped there.

Near Bruton Church, they took over a coach house, and

Confederate raids becoming too frequent for the comfort of Federals stationed hereabouts, a big black cannon was planted in the middle of the street, ostensibly to sweep the street with "grape and canister" should the rebels appear to the westward.

Further east, near today's Greenhow Store, Lee said,

was a very large, long, frame building. I can't recall whether this building was two and half stories or one and a half stories high. An old gentleman by the name of Hope kept a lodging here until the Yankees took it to use as a prison for their captives.

One townswoman confined herself:

The present Armistead house, then a new building, had just been occupied by its owner, a Virginia Yankee named Bowden, whose mother, because of his Northern sympathies, refused to live with him. She lived in a small, frame, story and a half house, which is now gone, on the rear of this lot.

At war's end, the Union soldiers marched away from a Williamsburg glad to see them gone, and reduced, like much of the conquered country, to narrow circumstances. People made hard cash of what they could salvage in the wreckage. At the Palace Farm, Charles said,

were the remains of what had once been an oil factory. Castor beans were once raised on this place, and the huge iron cubes used in pressing out the oil were sold to a junk dealer whose vessel lay at the College Landing during the summer of 1865, when it was "root pig, or die," and dimes looked like door knobs… .

In the 1860s, the word "reconstruction" meant something much different than it would in the 1930s. In the Baptist Church basement, schoolmarms dispatched by the Freedman's Bureau taught the Three Rs to former slaves. Outside town, government agents parceled out abandoned farms to African American husbandmen. Sometimes, when former owners returned, there was resistance. Newspapers as distant as Kansas and Scotland carried this item in 1867:

Trouble with the negroes near Williamsburg is reported. They refused to pay rent for property which they were occupying, and upon a demand being made by the agent of the Freedmen's Bureau, they armed themselves and repeated their refusal. A messenger had been sent asking the interference of the military.

Charles preferred to remember what seemed to him to be better times:

In this old and historic city, in the days of which we write, there were no pavements; no street lights; no railroad, hence no depot; no express office; no telegraphy office; no telephones; no phonographs; no radios; no post office money orders; no banks; no public schools; no automobiles; and no motorcycles and no bicycles. Still, most of our people were educated and refined, and many having a sufficiency of this world's goods, were happy and content; and when the war trumpet sounded in 1861, there went forth from here a band of as brave men and as noble women, to join the Southern host to do or die in defense of right, as ever will be marshaled again anywhere, in defense of any cause.

Extra Images

Colonial Williamsburg Collections

John Blair House on Duke of Gloucester Street near Merchants Square.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Carol Kettenburgh Dubbs, Defend This Old Town: Williamsburg during the Civil War (Baton Rouge, LA, 2002).

- Earl C. Hastings Jr. and David S. Hastings, A Pitiless Rain: The Battle of Williamsburg, 1862 (Shippensburg, PA, 1997).

- Carson O. Hudson Jr., Civil War Williamsburg (Mechanicsburg, PA, 2010).