When Whiskey Was the King of Drink

by Mary Miley Theobald

Photos by Dave Doody & Tom Green

Farmers in the backwoods made their own clothes, grew their own food, distilled their own whiskey. As perhaps one of the Whiskey Boys who turned violent in 1794, when the government tried to tax alcohol, David Nielsen overindulges from the jug.

George Washington turned from politics to potables when he left the presidency. The distillery he built at Mount Vernon boiled up 11,000 gallons of whiskey in 1798. Here, Ken Johnston as Peter Bingle, Washington’s man of moonshine, in the rebuilt distillery.

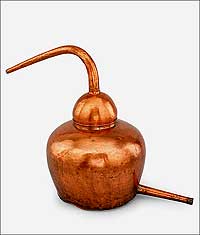

A copper kettle for homemade spirits, from Lancaster, Pennsylvania, in the second half of the eighteenth century.

In Culpeper County, Virginia, Chuck Miller sits on his still. In 1986, he squashed grape growing in favor of corn mashing.

Virginia farmer Chuck Miller gave up wine for whiskey twenty-two years ago. “Growing grapes just didn’t work,” he says. “One day I came across my grandfather’s old recipe for moonshine and decided to try to make that—legally this time.” He got a license, bought a 1935 bottling machine and an antique pot still, and started distilling corn whiskey on his Culpeper spread.

Miller says he’s following in his grandfather’s Prohibition-era footsteps, but whiskey making in Virginia goes back farther than that. It began about 1620, when colonist George Thorpe figured out he could distill a mash of Indian corn. “Wee have found a waie to make soe good drink of Indian corne I have divers times refused to drinke good stronge English beare and chose to drinke that,” he wrote to his cousin in England, John Smith of Nibley.

Thorpe came to the Old Dominion as a preacher, physician, and surgeon to take charge of the 10,000 acres and 100 indentured servants owned by the newly chartered College at Henricus, near the confluence of the Appomattox and James Rivers. How he came about his distilling skills is something of a mystery. He was an Englishman with no discernible link to whiskey’s originators—the Irish and the Scots. The son of landed gentry, he studied at Cambridge and was a member of Parliament and the Privy Council. One of four investors who established Berkeley Hundred, a few miles up the James from Jamestown, in 1619, Thorpe became an advocate for the Powhatan Indians, who he said had a “peaceable & vertuous disposition.” He criticized fellow colonists for ill-treating the Powhatan. “If there bee wronge on any side it is on ors who are not soe charitable to them as Christians ought to bee,” he wrote. When warned of an imminent Powhatan uprising, he refused to flee, believing the Indians would not harm their friends. March 22, 1622, the Indians killed him and mutilated his corpse. The inventory of his belongings included “a copper still, old,” valued at three pounds of tobacco.

Legend credits Irish monks with whiskey’s invention. Traveling in the Middle East during the Crusades, they realized the copper alembics they saw used to make perfume could produce medicinal spirits, too. The word whiskey comes from the Gaelic for “water of life”—uisgebeatha or whiskybae. Nearly any grain can be used to make it. In Ireland and Scotland, barley is traditional; in early America, where maize grew better than barley, corn or rye or both were used. But whiskey did not catch on in America until the eighteenth century.

Distilleries grew up in New England around the rum business. Rum was a link in a chain that dispatched ships freighted with rum to Africa to trade for slaves who were transported to the West Indies to grow sugar to make molasses to ship to New England to make rum . . . and so forth. Of course, rum was consumed at home as well. It was cheap and readily available in every tavern in every American colony. Whiskey rarely appears on tavern price lists before the Revolution. About a quarter of a million Scotch-Irish came to the American colonies in the fifty years before independence, making them the largest immigrant group of that century. They brought with them a fiercely independent spirit, abhorrence for government regulation, and an affinity for whiskey.

Any frontier farmer who raised more grain than he could eat or feed to his livestock could distill whiskey at home. If he didn’t own a still, he found a neighbor who did and gave him a portion of the whiskey as payment. A bushel of corn made about three gallons and was worth more in liquid form. Rye and corn became the preferred grains of colonial whiskey makers, with rye the main ingredient. Whiskey made principally with corn developed later in the eighteenth century in the backwoods of Virginia known as Kentucky.

The Revolution meant the decline of rum and the ascendancy of whiskey in America. When the British blockade of American ports cut off the molasses trade, most New England rum distillers converted to whiskey. Whiskey had a patriotic flavor. It was an all-American drink, made in America by Americans from American grain, unlike rum, wine, gin, Madeira, brandy, coffee, chocolate, or tea, which had to be imported and were taxed.

Faced with Revolutionary War debts, however, Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton moved in 1791 to tax domestically produced spirits. Distillers demanded repeal, saying the levy, an excise, fell disproportionately on the poor. Moreover, they were “apprehensive that this excise will by degrees be extended to other articles of consumption, until everything we eat, drink, or wear be, as in England and other European countries, subjected to heavy duties and the obnoxious inspection of a host of officers.”

Most of these objectors were small Scotch-Irish whiskey makers. They lived in the mountains of western Pennsylvania and Virginia, where government intrusion was minimal and personal independence was a religion. When petitioning for repeal failed, many of the larger, highly visible New England distilleries paid the duty; most of the frontier manufacturers refused and launched what came to be known as the Whiskey Rebellion in 1794.

A group calling themselves the “whiskey boys” went on a rampage, burning tax collectors’ homes, tarring and feathering excise officers, and destroying property of any who complied with the tax. Thousands of whiskey boys marched on and occupied Pittsburgh. Reluctantly, President George Washington called out the militia. The rebellion collapsed. A few rebels were captured, convicted of treason, and sentenced to death. Washington pardoned them.

History books have long presented a sympathetic picture of the whiskey boys, saying that their livelihoods depended on the sale of spirits to consumers on the other side of the Appalachians. “Supposedly,” writes historian Andrew Barr, “it was impractical for the backwoodsmen to haul bulky consignments of grain over the mountains,” so they turned it into more easily transported whiskey. “This was a myth created by their descendents. There is no evidence of backwoods whiskey being sold in eastern Pennsylvania in the eighteenth century. . . . The backwoodsmen drank it all themselves.”

Farmers on Virginia’s frontier began making whiskey with corn instead of rye in 1789, but what made it distinctive was aging. The Virginians discovered that charring the inside of oak barrels gave their matured whiskey a superior flavor and dark, rich color. In 1792, western Virginia became the state of Kentucky. Much later in the next century, people would call this corn whiskey “bourbon.”

Resistance to the whiskey tax continued to the point that it became uneconomical to collect, and the government repealed it in 1802. Now frontier whiskey could be sold tax free, and so could New England rum. Whiskey was still cheaper, though, because there was an import duty on molasses and none on domestic grains. It was so cheap, wrote a Kentucky doctor, “The poorest man in the community can get drunk as often as his wealthiest neighbor.”

Distilling whiskey on the family farm was common; commercial distilleries were not. In 1797, Washington started at Mount Vernon what would quickly become the largest commercial distillery in Virginia. The credit goes to Washington’s overseer, James Anderson.

Anderson had more than a nodding acquaintance with whiskey from his Scotch-Irish heritage, and it was he who proposed a Mount Vernon distillery. At first, Anderson used wheat, but he soon settled on a recipe of about two-thirds rye, one-third corn, plus a little barley. He began with two stills and produced eighty gallons in February 1797. By June, Washington was persuaded to expand. He would construct a stone building next to his mill. “Distillery is a business I am entirely unacquainted with,” wrote the former president to his overseer, “but from your knowledge of it and from the confidence you have in the profit to be derived from the establishment, I am disposed to enter upon one.”

The stone distillery had five stills and a boiler. Anderson’s son John became the chief distiller and six slaves—Hanson, Peter, Nat, Daniel, James, and Timothy—helped. The next year they made 11,000 gallons of whiskey for a profit of $7,500—a huge sum in those days. Washington grew his own rye and corn, and manufactured his own barrels. The waste mash fattened his hogs and cattle.

Washington died late in 1799, and the distillery passed to his nephew, who operated it for years. After 1808, written records fall silent. In 2006, Mount Vernon excavated the site and reconstructed the distillery atop the original foundations. It is the only eighteenth-century working distillery in the country.

For a couple of centuries, Americans thought drunkenness was deplorable, but drinking alcoholic beverages was healthful and should be encouraged. Strong drink restored one’s energy, kept one warm in the winter, and cured colds, fevers, headaches, depression, and snakebites. Physicians prescribed it, and alcohol was the primary ingredient in most medicines. Spirits were part of the democratic process. No election was complete without candidates treating voters—all of them white males—to a bottomless cup. Water was thought to be unhealthful; even when clean it lacked nutritional value and was considered fit only for livestock.

Water generally was unhealthful—few had access to clear mountain springs, rainwater was unreliable, and most wells were shallow. The water most people could drink was likely to be muddy, brackish, cloudy, or polluted, or taste of iron. It was safer to drink home-brewed small beer, hard cider, whiskey, or, if finances allowed, imported wines or spirits. And hadn’t the Apostle Paul himself urged in his epistle to Timothy to “drink no longer water, but use a little wine for thy stomach’s sake and thine often infirmities”? Ministers preached against drunkenness, not against drinking. They were drinkers and distillers themselves, and it was said that a preacher developed the first bourbon.

Not until 1784, when Dr. Benjamin Rush, the nation’s foremost physician and a signer of the Declaration of Independence, wrote his “Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits,” did people start to reexamine these beliefs. Rush had no quarrel with beer or wine, but he said excessive indulgence destroyed health. He was the first to describe alcohol addiction as something other than moral weakness.

After the Revolution, whiskey’s low cost and easy accessibility caused consumption to rise. Historian W. J. Rorabaugh writes that during the colonial period, the annual intake of hard liquor was about 3.7 gallons per person older than fifteen. At its peak in 1830, it exceeded seven gallons, roughly triple today’s.

Foreigners traveling in America commented in letters and diaries on the astonishing amount of hard liquor drunk at every meal, every occasion, and all through the day. One much-traveled woman wrote in 1830, “When I was in Virginia, it was too much whiskey—in Ohio, too much whiskey—in Tennessee, it is too, too much whiskey!” Not surprising when the price of a gallon of whiskey was about one dollar, and the average acre of grain yielded up to forty gallons. Many people became alarmed at the soaring drinking rates, including Thomas Jefferson. Jefferson’s efforts to launch an American wine industry were prompted by more than his own love of wine. He wrote to the secretary of the treasury in 1818 to encourage measures that would spread the drinking of wine and beer, avoiding “the poison of whiskey which is destroying” the middling class “by wholesale.”

Cheap, unregulated, and patriotic, whiskey was King of Beverages from the American Revolution through the Civil War, after which consumption began to decline. One of the reasons was a tax placed on whiskey in 1862—once again—to help pay for war. As the price climbed, drinkers shifted to cheaper substitutes such as beer, which grew in popularity along with the number of German immigrants.

The Temperance Movement was also having its effect. The 7.1 average per-capita consumption of spirits in 1830 plunged to 3.1 in 1840 and 1.8 in 1845—the lowest level of the nineteenth century. Still, the movement looked unlikely to achieve the goal of zero through persuasion alone, so it turned to enforced abstinence. Teetotalers advocated government legislation to force people to stop making, selling, or drinking any alcoholic beverage.

Consumption began to climb after 1900, and with it came a rise in prohibition fervor. Most of the increase was in beer; only in the South did the preference for whiskey continue. Several states, including Virginia in 1914, adopted laws mandating statewide prohibition. With the Eighteenth Amendment and Prohibition, the whole country went dry January 16, 1920. But the Scotch-Irish in the mountains of Virginia never stopped making whiskey.

Within a few years, many states gave up trying to enforce a law everyone was flouting. By 1933, President Franklin D. Roosevelt was calling for the amendment’s repeal. The next year, Virginia adopted the Alcoholic Beverage Control system in which the state monopolizes the sale of spirits, though not beer or wine. It was still illegal to make whiskey without a license, however, and Virginia required licensed distilleries to pay the cost of a federal inspector on the premises. “That was a way to keep the little fella from making whiskey, since he couldn’t afford a full-time inspector,” farmer Chuck Miller said. That requirement was removed in 1978, and a host of small Virginia distilleries applied for licenses, including Miller’s own Belmont farm.

Still, the law prohibited distilleries from selling their product except to the ABC board. Miller didn’t think it was fair that he couldn’t sell directly to the consumer: “I got my state representative, and we went to Richmond, and we asked how come a winery can make wine from their own grapes and sell it on-site to the public, but a distillery making whiskey from its own corn couldn’t.” There seemed to be no good answer, so in 2006, the law was changed. Miller now sells his two products—moonshine and bourbon—on the premises to visitors. And unlike his grandfather, he doesn’t need a fast car to outrun the revenuers.

Suggestions for further reading: