Rattle-Skull, Stonewall, Bogus, Blackstrap, Bombo, Mimbo, Whistle Belly, Syllabub, Sling, Toddy, and Flip

Drinking in Colonial America

by Ed Crews

Photos by Dave Doody

An afternoon's pleasure of company, cards, and rum. From left, Chris Allen, Phil Schultz, Jason Gordon, and Bill Rose.

From left, Pete Wrike, Menzie Overton, Terry Dunn (hidden), Marilyn Jennings, Virginia Brown, Bryan Simpers, Erin Wright, Spencer Chestnut, and Adam Wright toast a wedding.

Imbibing with the birds was one of the daily liquid breaks colonists enjoyed. Jason Whitehead takes a bed-rising nip.

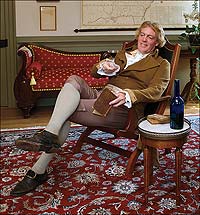

Jefferson, here Bill Barker, picked up a taste for fine wines as ambassador to France and later imported them to America.

A bucket of beer was often a standard part of the workday for tradesmen. Barbara Scherer serves the suds to, from left, Garland Wood, Steve Chabra, Wes Watkins, and Robert Watson.

A keg offered refreshment to the militia: Robert Rowe, Andrew Ronemus, Justin Liberta, Chris Geist, Josh Bucchioni, Dale Smoot, Colin Brauer, Terry Yemm, and Stephanie Flischel.

The father of the country was also captain of the whiskey industry. At Mount Vernon's distillery, Ken Johnston as Washington's distiller Peter Bingle takes the temperature of the copper kettle.

Editor's note: Autumn and winter holidays bring to festive American tables all manner of drink, from fine wines to grocery store eggnog. The celebrations of Thanksgiving, Chanukah, Christmas, and New Year's are traditional justifications for raising a convivial glass with friends and family. Early Americans neither needed nor waited for such excuses.

Colonial Americans, at least many of them, believed alcohol could cure the sick, strengthen the weak, enliven the aged, and generally make the world a better place. They tippled, toasted, sipped, slurped, quaffed, and guzzled from dawn to dark.

Many started the day with a pick-me-up and ended it with a put-me-down. Between those liquid milestones, they also might enjoy a midmorning whistle wetter, a luncheon libation, an afternoon accompaniment, and a supper snort. If circumstances allowed, they could ease the day with several rounds at a tavern.

Alcohol lubricated such social events as christenings, weddings, funerals, trials, and election-day gatherings, where aspiring candidates tempted voters with free drinks. Craftsmen drank at work, as did hired hands in the fields, shoppers in stores, sailors at sea, and soldiers in camp. Then, as now, college students enjoyed malted beverages, which explains why Harvard had its own brewery. In 1639, when the school did not supply sufficient beer, President Nathaniel Eaton lost his job.

Like students and workers, the Founding Fathers enjoyed a glass or two. John Adams began his days with a draft of hard cider. Thomas Jefferson imported fine libations from France. At one time, Samuel Adams managed his father's brewery. John Hancock was accused of smuggling wine. Patrick Henry worked as a bartender and, as Virginia's wartime governor, served home brew to guests.

The age of the cocktail lay far in the future. Colonists, nevertheless, enjoyed alcoholic beverages with such names as Rattle-Skull, Stonewall, Bogus, Blackstrap, Bombo, Mimbo, Whistle Belly, Syllabub, Sling, Toddy, and Flip. If they indulged too much, then they had dozens of words to describe drunkenness. Benjamin Franklin collected more than 200 such terms, including addled, afflicted, biggy, boozy, busky, buzzey, cherubimical, cracked, and "halfway to Concord."

If most Americans loved their drink, many to excess, not everybody was so sure that immoderate alcohol consumption was a good idea. As early as 1622, the Virginia Company of London wrote to Governor Francis Wyatt at Jamestown complaining that colonist drinking hurt the colony. James Oglethorpe, founder of Georgia, feared rum would ruin his venture and tried to ban it. Puritan leaders attacked drunkenness, although they also saw alcohol as a necessary part of life. Franklin enjoyed a convivial drink but called for moderation, writing "nothing is more like a fool than a drunken man."

Most Americans saw excessive drinking as a simple lack of will. If people wanted to stay sober, the argument went, they would. The notion of a relationship between alcohol and addiction did not exist for much of America's first 150 years.

In the late 1700s, Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia physician and signer of the Declaration of Independence, became fascinated with mental illness. Today, he is considered the father of American psychiatry. He took a special interest in alcoholism and penned a work on the topic, Inquiry into the Effects of Ardent Spirits Upon the Human Body and Mind, published in 1785.

Rush saw alcoholism as a disease—not a failure of will—and an addiction. As he put it: "The use of strong drink is at first the effect of free agency. From habit it takes place from necessity." He said the only cure was abstinence. His advice to alcoholics was: "Taste not, handle not."

Rush's thinking played a role in shaping the temperance movement in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as well as modern ideas about alcoholism, but it had little impact at the time.

Early Americans really did not care what anybody thought about their love of alcohol. As a Georgian wrote: "If I take a settler after my coffee, a cooler at nine, a bracer at ten, a whetter at eleven and two or three stiffners during the forenoon, who has any right to complain?"

In 1790, United States government figures showed that annual per-capita alcohol consumption for everybody over fifteen amounted to thirty-four gallons of beer and cider, five gallons of distilled spirits, and one gallon of wine.

Americans thought alcohol was healthful. To their minds, drink kept people warm, aided digestion, and increased strength. Not only did alcohol prevent health problems, but it could cure or at least mitigate them. They took whiskey for colic and laryngitis. Hot brandy punch addressed cholera. Rum-soaked cherries helped with a cold. Pregnant women and women in labor received a shot to ease their discomfort.

Water, on the other hand, could make you sick. Though the New World had plenty of fresh, unspoiled water, incautious Americans sickened and sometimes died by drinking from polluted sources. Jamestown gentleman George Percy, relating the troubles of the settlement's early days, wrote that the colonists' drink was "cold water taken out of the River, which was at a floud verie salt, at a low tide full of slime and filth, which was the destruction of many of our men." In some cases, even when it was safe to drink, river water had so much mud that a bucket of it needed to sit long enough to allow suspended material to settle.

In Europe, where polluted waterways were a bigger problem, people substituted alcohol. It was an easy example for the colonists to follow.

The first beverages of choice were cider and beer. Both were simple to make. For cider, the raw material, apples, was readily available. For beer, they turned to corn, wheat, oats, persimmons, and green cornstalks.

In 1612, the Dutch opened in New Amsterdam the first brewery in what would be British America. Breweries began to supply ordinaries and taverns. In larger population centers, this worked well, because beer did not keep. Cities had enough drinkers to consume the beer before it spoiled.

The first Europeans thought that the New World would be a perfect place to make wine. It was not. European grapevines did not survive American pests and diseases. Successive experiments in establishing vineyards failed in Virginia, New England, Maryland, South Carolina, Pennsylvania, and Georgia. Colonists did use native grapes to make wines, but these never supplanted European imports.

Jefferson was a passionate wine advocate and connoisseur. He became interested in wines and viticulture during his diplomatic service in France during the 1780s, taking time to tour vineyards in Alsace, Burgundy, Bordeaux, Champagne, and the Rhone and Rhine Valleys. He collected wine, bought 20,000 bottles of European imports as president, and advised George Washington, John Adams, James Madison, and James Monroe on vintages. Jefferson called for grape cultivation in the United States. Like everyone else, though, he failed at it.

Madeira was popular. It came from the Portuguese Atlantic island of that name. This beverage not only survived the long ocean voyage but improved with the tossing in a ship's hold. It also proved resilient in the steamy South. About 1750, somebody decided to fortify Madeira with brandy. The new taste appealed to Americans, and Madeira became the preeminent wine in British North America.

As time passed, distilled spirits became popular and widely available. They required more equipment and skill than beer and cider but made better economic sense for producers. The raw materials were available—grapes, plums, apples, blackberries, pears, and cherries. Peach brandy, a Southern specialty, was popular, as was applejack, which came from distilling cider. Distilled spirits kept longer than cider or beer, and because of their concentration of alcohol, were more potent. From the standpoint of intoxicant per ounce, they took less space than beer or cider and could be more easily transported. Those factors helped contribute to the success of rum in America.

Rum was king of the colonies before the Revolutionary War. It was made from molasses imported from Caribbean sugar plantations. Sometimes the raw material arrived legally; sometimes it was smuggled.

By 1770, the colonies had more than 140 rum distilleries, making about 4.8 million gallons annually. That was on top of the 3.78 million gallons imported each year. Production was concentrated in the Northeast.

American rum was inferior to Caribbean, but the domestic stuff was cheap and available. For example, a gallon of American rum cost 1 shilling and 8 pence in Philadelphia during 1740. The smoother, better Caribbean variety went for 2 shillings and 5 pence. With prices for domestic alcohol so low, almost anybody could afford it. It is difficult to know just how much rum colonists drank in British North America, but one historian estimates that during the 1770s the average adult male may have consumed as much as three pints weekly.

Rum was a powerful economic engine. Demand for it became the foundation of colonial intercoastal and international trade. Distillers exported their wares to England, Ireland, southern Europe, and Africa. The beverage was integral to slaving. Rum for that business was distilled several times to make a concentrated product. This saved storage space on ships, as captains could cut their cargo with water upon arrival in Africa.

Whiskey began to gain ground during and after the Revolution. Whiskey was made in America before the conflict, though its production typically was limited to farmers who had surplus grain. This began to change when war and the Royal Navy made molasses imports expensive and irregular. Denied large quantities of rum's raw material, Americans turned to domestic whiskey. Whiskey gained popularity after the conflict as a new sense of American identity flourished and patriots sought a beverage devoid of English ties.

The new nation's whiskey makers tended to be Scotch-Irish immigrants. Their settlements in Pennsylvania, Maryland, western Virginia, and western North Carolina become hot spots of alcohol production that used a mix of rye and corn. By the late 1700s, Kentucky began developing a reputation for its distillers' skill. Nobody knows if one person can take credit for this, but the whiskey of Bourbon County, Kentucky, gained a national reputation and following. The state had the right resources for making a quality drink. It was blessed with a ready supply of corn, limestone-filtered water, and hardwood for barrels.

Before the nineteenth century, Kentucky producers started shipping barrels of their whiskey by river to New Orleans. At the end of the long trip, the contents had taken on a distinctive reddish color from the charred barrels in which they were stored. By the early 1800s, Kentucky whiskey resembled modern bourbon.

Early on, George Washington recognized whiskey's moneymaking potential. After his presidency, he was casting about for a way to increase Mount Vernon's cash flow. James Anderson, his plantation manager, suggested a distillery. By 1798, the father of our country had a solid building in which several stills were bubbling away. Mount Vernon's whiskey production went from 600 gallons in 1797 to 4,500 gallons in 1798 to 11,000 gallons in 1799. Washington died that year, and, at the time, he was one of the largest distillers in the United States.

The Mount Vernon estate recently reconstructed the farm's distillery and runs off an approximation of Washington's brand. The stuff is not whiskey as now known, but more like grain alcohol. Still, a market may exist for it. In 2007, the Virginia General Assembly passed a bill that allows Mount Vernon to sell commemorative spirits. Executive Director James C. Rees says Mount Vernon does not intend to become a serious whiskey producer.

"We have no plans to enter the high-stakes liquor business," he told a reporter, "even though it's tempting, given that the name of George Washington would certainly provide us with a sensational marketing advantage. We could say he was first in war, first in peace, and first in smooth libations."

Ed Crews contributed to the spring 2007 journal a story about voting in early America.