The Truth About Betsy Ross

Popular Lore Says She Made First Flag, but Evidence for the Tale Is Scarce

by Ed Crews

Betsy Ross shows General Washington the flag she created for the nation in her Philadelphia shop, or so we were told in school. But the facts are few and flimsy to support that account. From left, Ron Carnegie as Washington, Sam Miller, Brook Welborn as Ross, Mark Sowell, and Gerry Underdown as Col. George Ross.

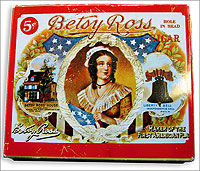

Betsy Ross merchandise runs from dolls to flags, a telling sign that her story—a mixture of fact and folklore—remains part of the national biography.

Mom, apple pie, the flag . . . and a good smoke. Hole in the Head 5¢ cigars thought an appeal to patriotism good for business.

A post-Revolutionary version, this official 1795 flag flew from Fort McHenry, inspiring Francis Scott Key’s “Star-Spangled Banner.”

Americans love the story of Betsy Ross’s making the nation’s first official flag. For almost 140 years now, the tale of the plucky, practical Philadelphia seamstress has occupied a comfortable niche in the country’s patriotic pantheon alongside the stories of Paul Revere, the Minutemen, and Valley Forge.

Ross is so beloved and so deeply embedded in the nation’s memory that somehow it seems unpatriotic, if not vaguely treasonous, to cast doubt on her story. The truth, however, is that nobody can prove that Betsy Ross had anything to do with the first official Stars and Stripes.

Marc Leepson is author of a popular 2005 history of Old Glory, Flag: An American Biography. He said in an interview, “As far as the big question is concerned—Did she make the first American flag?—every historical study has come to the same conclusion. There’s no good historical evidence that she did. But that doesn’t mean she didn’t. There’s simply a lack of documentation. Most historians believe the story is apocryphal.” But Betsy Ross has her supporters, regardless of academic consensus. The Independence Hall Association, for example, backs her. The association is a private organization that has supported and advised Independence National Historic Park in Philadelphia since 1942. At www.ushistory.org/betsy, the association gives Ross credit:

“Betsy Ross sewed the first American flag. When we view the flag, we think of liberty, freedom, pride, and Betsy Ross. The American flag flies on the moon, sits atop Mount Everest, is hurtling out in space. The flag is how America signs her name. It is no surprise that Betsy Ross has become one of the most cherished figures of American History.”

The Betsy Ross House, now a Philadelphia museum honoring the putative flagmaker, promotes her story but encourages visitors to decide whether it’s “historical fact or well-loved fiction.”

Ross’s renown rests in part on her story being told so often to so many. Millions of children learn about her every year in elementary school history classes. A thriving Betsy Ross industry supports the story’s perpetuation, too. Shoppers can buy Betsy Ross merchandise from dolls to pictures. And every Fourth of July, homeowners across the country salute her by proudly flying “Betsy Ross flags,” featuring thirteen alternating red-and-white stripes and thirteen five-pointed stars in a circle on a field of blue.

Opinions may differ on Ross’s contribution to the creation of the national colors. Yet all parties agree that American revolutionaries were using a variety of flags during the early 1770s to express their distaste for British rule. Some colonists made one that featured a British Union Jack sitting in the upper-left corner of a red field with the words “Liberty and Union” emblazoned in white along the field’s lower half. The tea-tossing Sons of Liberty flew a simple standard with alternating red and white stripes. Another popular ensign sported a coiled rattlesnake on a yellow or red-and-white striped background with the words “Don’t tread on me.” Immediately before the Declaration of Independence, probably the most used unofficial flag of revolution was the Continental Colors. This ensign had a Union Jack in the upper-left corner and alternating red and white stripes. Although unofficial, this banner saw service with American forces. It also had the distinction of being the first American flag saluted by a foreign power.

The Continental Colors, however, had a practical and a symbolic flaw. Because it contained the Union Jack, the flag could create confusion in a battle. When American soldiers raised it outside Boston, British troops thought the conflict was almost over. “By this time, I presume, they begin to think it strange that we have not made a formal surrender of our lines,” George Washington wrote. In addition, this flag did not represent reality. It implied a continuing tie to Great Britain just as a complete break was pending.

Congress recognized that the new nation needed a flag. On June 14, 1777, it passed the country’s first flag law. As legislation goes, it was refreshingly brief: “Resolved. That the flag of the United States be thirteen stripes, alternate red and white; that the union be thirteen stars, white in a blue field, representing a new constellation.” From a twenty-first-century perspective, the Continental Congress’s lack of guidance on the flag’s appearance seems extraordinary. The law said nothing about the flag’s size, shape, or ordering of stripes or the size, type, or arrangement of stars. The legislation implicitly gave flag makers latitude for the creation. So the fledgling United States probably could have used somebody like Betsy Ross to get things organized. The first hint that she did, however, did not surface nationally until almost a century after America declared independence from England. In 1870, her grandson, William Canby, told her story publicly for the first time, delivering a paper titled “The History of the Flag of the United States” to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania. According to Canby, Ross’s involvement with the flag began in 1776, a year before Congress passed its first flag resolution. He wrote:

Sitting sewing in her shop one day with her girls around her, several gentlemen entered. She recognized one of these as the uncle of her deceased husband, Col. George Ross, a delegate from Pennsylvania to Congress. She also knew the handsome form and features of the dignified, yet graceful and polite Commander in Chief, who, while he was yet Colonel Washington had visited her shop both professionally and socially many times, (a friendship caused by her connection with the Ross family) they announced themselves as a committee of congress, and stated that they had been appointed to prepare a flag, and asked her if she thought she could make one, to which she replied, with her usual modesty and self reliance, that “she did not know but she could try; she had never made one but if the pattern were shown to her she had not doubt of her ability to do it.”

The committee produced a conceptual drawing. Seamstress Ross did not like the design and suggested improvements. Washington agreed with her, grabbed a pencil, and revised the drawing. Canby did not know what these changes were with one exception. The drawing showed six-pointed stars; seamstress Ross reportedly wanted five points. The committee members said they took too much effort. Canby wrote:

“Nothing easier” was her prompt reply and folding a piece of paper in the proper manner, with one clip of her ready scissors she quickly displayed to their astonished vision the five pointed star; which accordingly took its place in the national standard.

According to the story, things moved swiftly from there. She made a prototype flag. The committee liked it. Congress approved it. And the Philadelphia seamstress became a flag maker for the fledgling nation. Colonel Ross fronted the operation, supplying a £100 advance for materials. Canby’s tale struck a responsive chord among Americans. They loved Washington’s role in the story as well as Ross’s character—an engaging mix of can-do spirit, common sense, and homespun ability.

By 1873, the Betsy Ross story was appearing in national journals. In 1909, Canby’s brother and nephew published a book, The Evolution of the American Flag. That volume cemented widow Ross’s place in the public mind.

Skeptics have doubted the tale for almost a century. Critics said then, as well as now, that it has charm but no documentary support, which Canby readily admitted. Ross’s grandson told the Pennsylvania Historical Society in his presentation that his research in Philadelphia and in Washington, DC, revealed nothing about who designed or sewed the first United States flag.

“The search was fruitless,” he said, “as might have been expected, as to the finding of any matter throwing light on the origin of the design, and the making of the flag. It was not fruitless in this, however, that it establishes the fact that no such history there exists; a fact not heretofore definitely stated.”

Canby relied on family oral accounts. None of Canby’s sources had witnessed Washington’s visit or his grandmother making the flag. Instead, all said they had heard her tell the story many times.

Today, historians almost uniformly agree that family oral history is not particularly reliable. Though evidence shows that Betsy Ross made flags for the Pennsylvania navy, nothing else in Canby’s story can be verified. Specifically, a few points trouble researchers: No evidence shows that a congressional flag committee existed in 1776. If one had, Washington probably would not have been on it because he was not a member of Congress. No record shows Congress addressing the flag issue in any way until it passed the 1777 resolution. Nothing suggests that Washington ever dealt with Betsy Ross for any reason. No written material of any sort supports the story.

We probably will never know who made the first flag. We do, however, have a good idea about who originated its design. Credit for that achievement may go to Francis Hopkinson, a New Jersey representative to the Continental Congress and signer of the Declaration of Independence. Hopkinson was a talented man with a strong interest in designing symbols. He played a role in creating the Great Seal of the United States, the Continental Board of Admiralty seal, treasury seal, and American currency. Documents also show that he worked on the first official United States flag. Hopkinson’s role was addressed in a series of letters in which he sought payment from the government for design work on projects, including the flag. Officials rejected his claim, alleging he received help on the flag, but acknowledged his contribution.

Though Leepson sees little harm in the Betsy Ross story, he says it may shortchange Hopkinson’s contribution to Old Glory’s creation. It seems odd so little definitively can be said about the creation of first Stars and Strips, or how often flags with stars and stripes were used during the Revolution. Apparently, though, the modern version of the “Betsy Ross flag” was not one of them. Physical evidence is rare. Many flags once hailed as survivors of the conflict have failed modern examinations. Many of them apparently were made in the 1800s. Certainly, some historians believe that they have found contemporary pictorial evidence, suggesting that a variety of American flags saw service in the conflict. Leepson says, “It’s all very fuzzy. With the absence of photos, we just don’t know what was used.”

Our knowledge improves when it comes to American flags made after the Revolutionary War. In 1795, a new official flag design appeared. It provided for fifteen stripes and fifteen stars, reflecting the addition of Vermont and Kentucky to the Union after the war. This flag flew over Fort McHenry. Francis Scott Key immortalized it in “The Star Spangled Banner.” Recently restored, it is now displayed at the Smithsonian in Washington, DC.

This version of the flag served until 1818, when national expansion began a long series of alterations to it. Perhaps none of those alterations is better remembered than the forty-eight-star version raised over Mount Suribachi by five Marines and a Navy Corpsman in 1945. It is now displayed at the Marine Corps Museum at Quantico, Virginia.

Despite the changes that flag underwent in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the Betsy Ross story has endured almost unaltered since its 1870 introduction. Although he has studied and written about the flag, Leepson says he is hard pressed to explain why the unproven Betsy Ross story has such staying power.

“Perhaps there’s something in the American psyche that just looks for heroes and heroines,” he said. “Then again maybe it’s just like the way things work when you visit patriotic sites in Philadelphia. The Betsy Ross house is on the tour. It’s almost a de rigueur stop as you move along to see Independence Hall, the Liberty Bell, and Christ Church. It’s just been woven into the fabric of the story.”

The Betsy Ross Challenge

Try your hand at creating a five-pointed star in a single snip with these step-by-step instructions.

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed to the winter 2008 journal story about Colonial Williamsburg's Canadian horses.