The Golden Age of Counterfeiting

Cashing in on Colonial Currency

By Jack Lynch

Online Extras

Sidebar: A Counterfeiting Silversmith

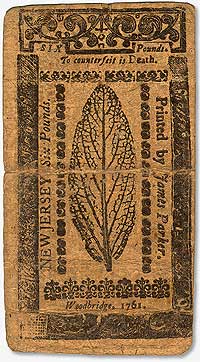

New Jersey issued this six-pound note in 1761, during the French and Indian War. It warned "To counterfeit is Death," because counterfeiting was deemed a capital offense.

In September 1995, the Washington Post reported a press conference in which the United States Department of the Treasury announced "the first major redesign of the nation's currency in 66 years":

Treasury Secretary Robert E. Rubin hailed the changes as "substantial," saying they offer new security to currency that is increasingly threatened by counterfeiters and high-tech copying machines...Treasury officials stopped short of claiming that the new bills will foil counterfeiters. "As the Secret Service tells us, there is no bill that is not counterfeitable, but this bill substantially raises the hurdle," said a senior Treasury official.

This was not the first time the United States government redesigned its money to stay ahead of counterfeiters. Such changes began before there was a Treasury Department—as historian David R. Johnson writes: "In the early eighteenth century, counterfeiting in America entered a kind of golden age that would last for roughly a hundred and fifty years." And these were high-stake years, because phony money threatened to weaken confidence in the finances of the young nation. Without trust in the dollar, there could be no commerce; without commerce, there could be no country. The history of America's money is largely a history of the struggle to keep a step ahead of the forgers.

Counterfeiting in America goes back to the first English settlements in the New World. Many Native American tribes used polished cylindrical shells as currency: the Algonquian word "wampumpeag" gave us the more familiar "wampum." In the early seventeenth century, not long after Europeans landed on the eastern seaboard, unscrupulous traders would dye the less valuable white shells to look like more valuable blue-black shells. Roger Williams wrote in his Key into the Language of America about the abundance of "counterfeit shell," and said that some Indians passed "stone and other materials" as if they were wampum.

As European American settlements grew and economies became established, coins took the place of shells. In order that "quoine may not be counterfeited," a Virginia law of 1645 required a new design of the colony's money every year—"a new impression which shall be stampted yearly with some new ffigure"—to make it difficult for the forgers to keep up with the changes. Virginia also provided that "capitall punishment" would be the penalty for "those who shall be found delinquents therein." But the added difficulty and the severe penalties were not always enough to discourage the dishonest.

A common practice was to clip or shave small amounts of silver or gold from each coin and to accumulate enough shavings to sell them as bullion. Coin clipping prompted monetary crises across Europe and its colonies, forcing people to rethink the notion of value. A shilling coin, for example, was supposed to contain one shilling's worth of silver—but, as the coins passed through one unscrupulous hand after another, more and more metal was trimmed, and the difference between intrinsic values and face values grew ever wider. In 1662, therefore, England began using machines to give coins milled edges, like the ridges that appear on modern dimes and quarters, which make it easier to spot clipped coins. But the older pieces remained in circulation until the end of the century, and they continued to be clipped. According to one estimate, by 1695, clippers had reduced the old handmade coins to about half of their original weight, the rest of the gold and silver circulating in an underground economy. It took a systematic revaluation of the currency, with all the old hand-minted coins removed from circulation, to solve the problem.

Holding a wampum belt, interpreter Dennis Watson and a member of the Eastern Band of the Cherokee nation.

As coin clipping became more difficult, would-be criminals turned from shaving money to making it. More than one reason made counterfeiting an appealing crime. For one thing, many acts of counterfeiting were not illegal. Most laws banned the forgery of the currency of a single colony, but clever malefactors could relocate to another colony—or, better yet, another country. Ireland, for instance, had no law against manufacturing American currency, and forgers set up workshops there. Over and over, we see cases of counterfeiting that remained within the bounds of the law, which forced legislators to revise statutes to compass new criminal practices.

Maryland's experience is typical. In 1638, the assembly declared it treasonable to counterfeit the king's coin—a felony warranting death. Thieves took to coin clipping, which the Maryland Assembly was forced to outlaw in 1661. But this expanded law considered only British coins: there was no restriction on coining or clipping foreign money. The legislators had to broaden the law again in 1707, declaring that anyone convicted of forging foreign gold or silver would be pilloried, whipped, and have both ears cropped. In 1758, it was time to widen the scope once more, making it illegal "to forge or counterfeit the Bills of Credit of Virginia, or the Provinces of Pennsylvania, New-York, East and West Jerseys, and the Three Lower Counties on Delaware."

Even under the more expansive laws, though, the odds of being caught were low, and most counterfeiters never faced prosecution. Because British coins were scarce in America, foreign coins were common. But the resulting variety of circulating coins—Spanish pieces of eight, Portuguese moidores, Dutch and German thalers—meant that honest dealers had trouble distinguishing the real from the bogus, and prosecutions were rare. The few criminals who were caught usually foolishly betrayed themselves, as when, in 1774, a London counterfeiter sent his young daughter to a shop to buy some beer for her father. As Kenneth Scott, the leading authority on early American counterfeiting, describes it, "When the landlord happened to observe to the little girl that the coppers were warm, she innocently replied that her daddy had just made them." Miscreants who did get caught could still hope for a happy ending. As Scott writes, "The jails of the day were extremely weak and poorly guarded, so that a counterfeiter who was caught knew that he had a better than fifty-fifty chance to slip out of the prison at night."

More troublesome than coins were banknotes, a relative novelty in the eighteenth century. Britain tried to prevent its colonies from using paper money, but, with so little precious metal available in her New World possessions, the colonies were forced to issue bills of credit—this at a time when most Europeans distrusted paper money. As America began its struggle for independence, though, it had to rely increasingly on paper to raise funds for the war. The public's faith in the new money was low, especially because the Continental bills really amounted to bonds payable after an American victory—an outcome some believed would never come. The widespread distrust of these war bonds prompted the Continental Congress to resolve on January 11, 1776,

that if any person shall hereafter be so lost to all virtue and regard for his country, as to "refuse to receive said bills in payment," or obstruct or discourage the currency or circulation thereof, . . . such person shall be deemed, published, and treated as an enemy of his country, and precluded from all trade or intercourse with the inhabitants of these colonies.

The resolution, though, did not put an end to the skepticism, and many tradesmen either refused to take the banknotes or demanded a premium for accepting them. Rampant inflation set in as the bills' value plummeted at exactly the time the fledgling government needed resources. George Washington wrote in a letter to John Jay that "a wagon-load of money will scarcely purchase a wagon-load of provisions." It didn't help matters when, in January 1776, the British government began undermining American independence by attacking the American economy: it turned out great quantities of sham American money, advertising in New York's Tory newspapers that "Persons going into other Colonies may be supplied with any Number of counterfeit Congress-Notes, for the Price of the Paper per Ream." Josiah Bartlett said it was a "most diabolical scheme to ruin the paper currency by counterfeiting it," noting that the fakes were "so neatly done that it is extremely difficult to discover the difference." The "Tory plan," he said, was "one of the most infernal that was ever hatched." It was also the first recorded instance of wartime financial sabotage, which has continued to the present. During the Second World War, the Nazis put concentration camp prisoners to work forging Allied currency, hoping to weaken the Allies' economies.

Even during peacetime, paper money posed problems for the governments and banks that issued it. The biggest difficulty, then as now, was that it is easily copied. Melting and casting silver and gold require not only expertise but expensive furnaces and workshops. But anyone with a printing press could turn out banknotes. The problem is that whatever can be printed by the virtuous can be imitated by the wicked. Since counterfeiting can never be prevented altogether, the idea has always been to make the process so complicated and time-consuming that the effort required will not be equal to the face value of the phony money. Printers of eighteenth-century currency resorted to special typefaces and type ornaments, sometimes cut by hand, in the hopes that counterfeiters would find it too expensive to reproduce the banknotes.

But the efforts were rarely successful: even when experts might be able to recognize fake bills, the merchants who had to deal with them were baffled. Historian Johnson writes, "Rural colonists were not very familiar with paper money because their daily lives did not revolve around commercial transactions; furthermore, they had a deep prejudice against it because they did not regard it as 'real' money." Because merchants lacked familiarity with authentic paper money, they could be fooled by some surprisingly amateurish counterfeits. Kenneth Scott catalogues some of the errors in forged colonial banknotes:

On bills made in Hammelbach justice was spelled instice; again, droit was made dpoit and counterfeit turned into couuterfeit; two crowns was converted into two crowes; thompson was written as thonnon; the second d was omitted from the word woodbridge; Raper (a signer's name) was copied as Reper, Parker was spelled with an h; the e was left out of the last syllable of december and the b out of publick; the m in the word quartam was upside down.

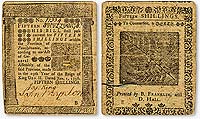

Such problems led Benjamin Franklin to devise a scheme to make life more difficult for counterfeiters. In 1739, a Pennsylvania twenty-shilling note, signed "Printed by B. Franklin," included realistic images of three blackberry leaves and a willow leaf. It was the first in a series of banknotes bearing images of leaves: they can be found on the colonial and revolutionary bills of Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and the Continental Congress.

Franklin was inspired by engraver Joseph Breintnall, who developed a technique for reproducing leaves. On Breintnall's nature prints there appeared a caption, "Engraven by the Greatest and best Engraver in the Universe"—God himself—because they seemed to go beyond the abilities of the best human engravers. The images are remarkably realistic: as numismatic historian Eric P. Newman put it, Franklin realized that "leaves not only had exceedingly complex detail but also that their internal lines were graduated in thickness. This would make virtually impossible a fine reproduction by engraving." As long as the technique could be kept secret, they would be as close to counterfeit-proof as anyone could hope for.

Benjamin Franklin's complex leaf design on the 1756 fifteen-shilling note he printed made it harder for forgers to counterfeit.

The founders were aware of these problems when they designed the United States Constitution. Article I, Section 8, grants to the federal government the power "To coin money, regulate the value thereof, and of foreign coin." But things did not improve in the early days of the republic: Johnson writes that "when the Civil War erupted, perhaps as much as half of the paper notes in circulation were counterfeit." Only after the Secret Service assumed responsibility for protecting the nation's currency in 1865 did the proportion of false money begin to decline.

The Secret Service, now part of the Homeland Security Department, still has the responsibility for anticounterfeit initiatives, and, though things are much better than they were before the Civil War, false currency remains a threat. Estimates of the amount of counterfeit United States money in circulation vary widely, but at least $62 million in counterfeit currency was removed from circulation in 2006. And so the struggle between forgers and governments, a strange kind of fiscal arms race, goes on. Each time counterfeiters master a new technology, the Treasury Department has to redesign its banknotes to make them a little more difficult to duplicate. A new series of bills appeared in the mid-1990s, for instance, and yet another round followed beginning in 2003, when the $20 bill was redesigned once again. The $50 bill followed in 2004, and the $10 bill in 2006; a new $5 bill is to be rolled out early in 2008, and the $100 bill is to follow. This latest series of bills includes such high-tech anticounterfeit devices as watermarks, security threads, and color-shifting ink. But these technological breakthroughs should not permit complacency: the counterfeiters will soon discover a way to reproduce the most advanced security devices we have today.

The long war between the government and the counterfeiters shows no signs of abating. That is why the Treasury Department has announced plans to redesign the currency every seven to ten years, as advances in security technology allow them to stay ahead of advances in counterfeiting. With each alteration of our money, the government pursues the struggle against a plague that has afflicted the nation since colonial days.

Jack Lynch, author of The Age of Elizabeth in the Age of Johnson (Cambridge University Press, 2003), is associate professor of English at Rutgers University in Newark, New Jersey. He contributed to the spring 2007 journal a story about Jefferson's ideas on a constitution.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Robert F. Batchelder, "The Counterfeiting of Colonial Paper Money as Seen through the Letters of Signer of the Declaration of Independence, Josiah Bartlett," Manuscripts 31, no. 3 (Summer 1979): 207–11.

- Stephen Mihm, "Accept No Imitations: The Campaign against Counterfeits, Past and Present," Common-Place 4, no. 4 (July 2004).

- Eric P. Newman, "Nature Printing on Colonial and Continental Currency," Numismatist 77 (1964): 147–54, 299–305, 457–65, 613–23.

- Kenneth Scott, Counterfeiting in Colonial America, 2nd ed., with a foreword by David R. Johnson (Philadelphia, 2000).

- Alan D. Watson, "Counterfeiting in Colonial North Carolina: A Reassessment," North Carolina Historical Review 79, no. 2 (2002): 182–97.

- Learn more about currency in our online Coins & Currency exhibit.