Volumes to Last for Centuries

Text by Ed Crews

Photos by Tom Green

The Colonial Williamsburg bookbindery near the Print Shop and Post Office in the Historic Area produces books one at a time. Books were expensive in the eighteenth century, and few could afford many.

America is awash in books. Every year, publishers flood stores large and small with hundreds of thousands of titles, works that join millions more already in bookcases and on library shelves. The Internet offers billions of bytes of hard-drive-choking tomes with a few clicks of a mouse. Hardback, paperback, digital, books are common, plentiful, and cheap. That has not always been so. As you learn at Colonial Williamsburg's bookbindery, in the 1700s, books were relatively rare and precious.

Generally speaking, in eighteenth-century America books were upper-middle- and upper-class indulgences. Thomas Jefferson collected 6,500 volumes. They became the core of the Library of Congress. But most readers contented themselves with a few works.

"Books were considered treasures," Master Bookbinder Bruce Plumley said. "A shelf could be called a library, and that single shelf could represent a large outlay. Books were status symbols. They showed that you were wealthy and educated."

Raw materials—paper and leather for covers—were expensive. Without machinery, production was relatively slow. Putting together a simple business ledger might take about thirty steps and twelve to twenty hours, depending on the item's size. But the time and work it took to make a book turned the linen rags from which paper was made and the hides used for covers into treasures. Craftsmen could create bindings of remarkable quality, books to last centuries.

Plumley and journeymen Dale Dippre and James Townsend keep alive the tradition of first-class bindery workmanship at Colonial Williamsburg. They not only make business ledgers and account books but also create some bindings that incorporate fine leathers, gold leaf, and decorative metal work.

Plumley learned the craft as a young man in England during the 1950s. He studied under Eric Burdett, an internationally recognized master. Plumley, too, has enjoyed global success. He has two Thomas Harrison Memorial Awards, which recognize outstanding bookbinding, and is a Fellow of Designer Bookbinding—a title bestowed on twenty-one people in the world.

He is also a book restorer and conservator who has worked on antique volumes, including two Gutenberg Bibles and books owned by British naval hero Lord Nelson.

During the eighteenth century, engineering-like skills and knowledge were required to make books strong and durable. A book's structure had to allow for repeated openings and closings, page fanning and tugging, falls to the floor, and being pulled from a shelf by a finger hooked on a spine. Covers required artistry.

In the 1700s, young men learned bookbinding through an apprenticeship. It usually began in their teenage years and ended in their twenties. Mastering the trade required hard work, dexterity, attention to detail, and a willingness and ability to handle painstaking tasks. By the time they became journeymen, apprentices had learned dozens of skills, including folding pages, collating them, stitching, gluing, and techniques for decorating covers.

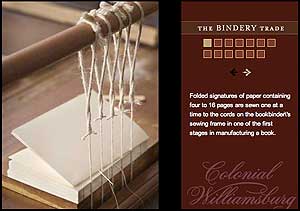

Book assembly was like constructing a three-dimensional jigsaw puzzle. Once the pages had come from the printer's, in the broadest terms, the process had two steps: forwarding and finishing. Forwarding generally involved arranging pages so they could be turned and examined. The most obvious work at this stage included arranging the pages in order and stitching them together. Townsend said stitching is one of bookbinding's easiest skills to master. It also is the essence of the craft. Once the pages were connected, the bookbinder put a protective cover on them, typically fashioned of leather from calves, sheep, or deer. The pages, folded in closed signatures, had to be cut open.

Finishing involved decoration. It could include lettering as well as design work. Bookbinders used heated tools to stamp or imprint a design in the leather. Eighteenth-century English decoration tended to be restrained. French work was more flamboyant. Colonial Williamsburg's bookbinders say that decorating books with gold leaf, twenty-four-karat gold sheets that are 250,000th of an inch thick, is the most demanding task. Among the variables are the heat of the tools, the type of cover, and the space allotted for a title on a spine. Everything is done by hand without benefit of a template.

"The last thing you do is the tooling, and it can make or break the project," Townsend said. "Gold tooling is ferociously difficult. But there's no doubt about it that when you're done with it, nothing looks as good as a gold-encrusted book."

Like most American craftsmen in the 1700s, colonial bookbinders tended to be generalists. In Great Britain, the trade could be far more specialized. Large shops in major cities could afford craftsmen who focused on one aspect of production. According to Plumley, a few bookbinders, like Samuel Mearne and Roger Payne, established reputations for skill that remain solid in the twenty-first century.

Bookbinders with high skills, working in the right shop, could expect satisfying jobs and pay. Williamsburg was an excellent location for a bindery. The Virginia colony's government needed documents bound. Teachers and students at the College of William and Mary wanted books. Planters, tradesmen, churches, ship captains, lawyers, and doctors needed account and ledger books. Printer William Parkes employed binders and kept them busy.

Their vocational successors Plumley, Dippre, and Townsend demonstrate a complex, detailed trade unlike any labor the average visitor encounters in today's world. The bookbinders say there is nothing else they would rather do.

"I love the work," Dippre said. "It definitely has a creative side to it. Like all work, it can be mundane, but we get enough variety and high-end projects that it's engaging and fun."

Ed Crews contributed to the spring 2005 journal an article on agriculture at Colonial Williamsburg.