"Every part works in harmony"

The Venerable Craft of Basketmaking

by Ed Crews

COLONIAL AMERICANS used baskets to haul grain, store sewing implements, and carry vegetables, fruits, and eggs. They did with baskets things that people have done with them time out of mind. Archaeologists have uncovered evidence of ancient basketry in places as diverse as Peru, Spain, Switzerland, and Oregon. For millennia, baskets, made of such natural materials as wood and reeds, were a means of toting individual loads. They are integral parts of myths and legends worldwide. Colonial Williamsburg basketmaker Richard Carr says, "Every civilization has made baskets. Basketmaking goes back before recorded history."

By the eighteenth century, the need for baskets had fostered a thriving English industry. Full-time basketmakers, members of a large and powerful guild that tried relentlessly to boost output and income, supplied much of the demand for their nation and its American colonies. Each basketmaker tended to specialize in a type of basket.

English basketmakers shipped many of their goods to America. Usually, people in cities and towns bought and used them. In rural areas, colonists often made their own—just as Carr and his Colonial Williamsburg colleague Terry Thon do. They employ years of research and experience, and traditional methods, to make the varieties of baskets typical of Virginia's eighteenth-century countryside. They are heirs of a venerable skill.

COLONISTS MADE BASKETS using skills taught them by their parents," Thon says. "They used whatever materials were at hand, and literally hundreds of materials were used." In Virginia, white oak was primary.

Farm basketmaking began early in Virginia's history and remained a common part of rural life until about World War II. After the conflict, a changing economy led country people to leave for cities. Rural basketry began to wane.

But in the Shenandoah Valley, Cody and Lucy Cook of Luray helped keep the craft alive. The couple began producing baskets in 1924, using skills learned at home in childhood. The Cooks had such success selling their products through local stores that they embraced the craft as a full-time business. In 1965, Colonial Williamsburg asked them to share their knowledge with guests and others. The Cooks also expanded the institution's knowledge of eighteenth-century baskets by reproducing varieties from period images. They made sure their knowledge would survive by teaching their techniques to Roy Black. Black, a thirty-year Colonial Williamsburg interpreter, mastered the craft and transmitted it to other interpreters, including Thon.

Today's Colonial Williamsburg basketmakers fashion basket types common in eighteenth-century Virginia, including square and round-bottomed models, small and large. The preferred construction material is white oak. It has a straight grain and is strong, flexible, and durable. As Carr and Thon note, though, no matter how fine white oak is, not just any piece of it will serve. Careful selection of raw material is important.

"You have to get the wood from the forest," Thon says. "What you need to find is a smaller tree between six and ten inches around. It has to be perfectly straight and can't have imperfections like knots, bug holes, or deer rubs. There are lots of myths, lots of folklore about finding trees and using them. All of these are supposed to help you in your selection."

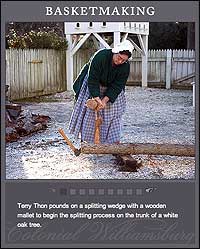

Once basketmakers have a tree, they fell it and take a five- to six-foot section. Using mallets, wedges, and knives, they reduce the trunk to long, thin strips of wood to weave into a basket, starting from the bottom.

When the sides are raised, they finish with a rim. Weaving should be snug. The key is to achieve the right tightness without unduly straining the wood. A basket for harvesting field crops might have large gaps to let rocks and dirt sift out. Other baskets might require a tight weave and a top to retain small items, like sewing pins.

Thon and Carr splitting the carefully selected log of white oak, the preferred wood in Virginia basketmaking.

BASKETMAKING IS ENJOYING a renaissance in the United States. Thousands of people construct baskets as a hobby. Baskets are home decorations and collector's items.

But materials and methods have changed. Colonial farm families did not use glue, nails, or forms to assemble baskets. Nor did they think of handmade baskets as primarily decorative. Some hobbyists are surprised that eighteenth-century Americans considered baskets tools, not art—more practical items than objects in which to invest emotion. "People in the 1700s saw baskets as strictly utilitarian objects," Thon says. "People didn't love them. They just used them."

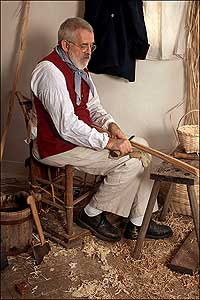

Carr and Thon enjoy guest interaction. And the work. It has given them respect for rural craftsmanship. To them, baskets are triumphant unities of design, engineering, and practicality. Carr says the longer he makes baskets, the more he sees them as a marriage of form, function, and material.

Looking at a large round basket in his lap, he says, "Everything in basketmaking works together. Nothing is superfluous. Every part works in harmony.

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed to the winter 2006 journal an article on Colonial Williamsburg's masonry trades.