Gambling

Apple-Pie American and Older than the Mayflower

by Ed Crews

photos by Dave Doody

From left, interpreters Russell Wells, John Hamant, and Dennis Watson mix wine and wagers at a tavern card table.

Charles II, here in a contemporary portrait, reclaimed the throne in 1660 and brought with him a taste for gaming.

An uncut sheet of eighteenth-century French playing cards. Cheats, professional and amateur, created a need for rules in card games, developed “according to Hoyle.”

Hogarth’s series The Rake’s Progress tours the shadowy corners of a vicious life—vicious in its eighteenth-century meaning of being addicted to vice—including this scene at the gaming tables, where the young rake seems possessed by a gambling fever.

Thomas Rowlandson, brother satirist to Hogarth, painted his version of a gaming den in The Hazard Room. On the walls is a bouquet of gambler’s delights: boxing, horse racing, the odds of the day, and the patron saint of card games, Edmond Hoyle.

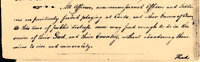

The 1776 order from General Washington’s headquarters that vainly attempted to restrict gambling by soldiers during the Revolutionary War.

In 1660, Charles II restored the English monarchy to the throne after a lengthy exile abroad, bringing with him a robust love of life. It was a welcome contrast to the dark years preceding his reign—a time of brutal civil war and grim Puritan theocracy.

For many of his subjects, Charles was the “merrie” king, attracted to horses, women, and, above all else, gambling. At his court, games of chance became a focus of life. The aristocracy aped the king; commoners aped them. And, before long, one of history’s gaming frenzies had the nation in a firm, loving embrace.

The madness not only spread to England’s every corner but roared, like a gale, across the Atlantic and beset the North American colonies. Colonists, like their cousins in Europe, began betting on anything and everything.

Although Charles II gave gaming a kingly cachet, wagering had come to America long before his time. Native Americans were gambling before colonists arrived, and early arrivals were surprised to find native peoples risking all they owned on games of chance.

Early on, Jamestown colonists encountered native gambling, said Nancy Egloff, historian with the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation. One English report compared stick and straw games to cards. “They will play at this for their bows and arrows, their copper beads, hatchets, and their leather coats,” an observer wrote.

Elsewhere, colonists saw Native Americans bet on the outcome of athletic events. Roger Williams witnessed an intense football-like game accompanied by enthusiastic sideline wagers. Native Americans also played a game that used peach pits as dice, and some eastern Indians had six-sided dice made from animal bones and painted black and yellow. Games could go on for days, during which villages and tribes played and exchanged huge amounts of goods. Some of this zeal stemmed from native beliefs that gaming was a gift from the gods and had a spiritual dimension.

Though important within their own cultures, Native American practices had little influence on Englishmen. Europeans played games brought from home, games shaped by tradition, urban and rural life, and western attitudes. During the Elizabethan and Stuart periods, gambling was widespread and popular. William Shakespeare’s plays are filled with gaming references; he and his audiences knew the subject well. Of the many forms gambling took, cards and dice trumped everything. Having crossed the Channel from France in the 1500s, cards were still a novelty during Elizabeth’s reign. Dice were much older, and they showed up everywhere. Recent Jamestown archaeological digs have found twelve dice and what appears to be a peg used in a gambling game similar to backgammon.

Gambling quickly became a problem in Virginia. Captain John Smith complained about men “devoted only to idleness.” The colony adopted “The Laws Divine, Morall and Martial” in 1610 and 1612 to try to control behavior, gambling not the least. The rules didn’t change much, though, and that led to another crackdown and more laws in 1619 addressing “idleness, gaming, drunkenness and excesse in apparel.” Apparently, these did not have much effect either.

In New England, Puritans took a dim view of the vice. Cotton Mather called it “a great dishonor of God.” The prevailing view was that gambling was inherently sinful and led men from God’s grace. Gaming also was “a door and a window” through which man could pass to worse sins. The Pilgrims established punishments ranging from substantial fines to whippings. Rules, sermons, and the lash, however, couldn’t control human nature. By the 1670s, gambling was a well-established feature—and irritant—of New England life.

Puritan disdain for gambling didn’t change human nature in either the New or Old Worlds. Oliver Cromwell tried mightily to stamp out games of chance in England when he controlled the country after the Civil War. He failed, and his repressive measures laid the foundation for the binge Charles II initiated. Tired of Puritan repression, Englishmen and -women were ready for a little fun in 1660.

Of course, that wasn’t the only reason gambling took off. Thanks to Charles’s royal endorsement, gaming was not only fashionable but also a sign of good breeding, so the aristocracy took up cards and dice. There was more disposable income because of the rising wealth of a new mercantile class accustomed to taking risks in business. In America, the tobacco planters were the counterparts of these Englishmen. Without eliminating chance, which is gambling’s allure, the study of probability provided those players with new ways to view and to conduct gambling, providing a framework for making decisions while playing.

Even now, in an age when poker games are televised and television dramas are set in casinos, it is hard to appreciate what Charles unleashed. Gambling in the English-speaking world was a powerful economic and social force from the 1660s—with some waxing and waning—into the 1800s.

Englishmen bet on everything: bull baiting, dog fights, backgammon, chess problems, military actions, sieges, births, deaths, walking and running contests, and cricket games. Just about everybody from preachers to playwrights commented on the phenomenon. Casanova was stunned at the English devotion to betting. Undoubtedly, he readily understood Charles’s other great interest—his mistresses.

One of the enduring legacies of the period was the creation of London’s gaming houses, which evolved because of crackdowns that drove gambling from public places, like coffeehouses, to private clubs. In the club called White’s, John Montagu, Earl of Sandwich, allegedly invented the food item that bears his name. In time, these establishments became the playgrounds of the rich and powerful, who also carried their activities to fashionable spas in the nation. Americans visiting London frequently played in the casinos. Virginia grandee William Byrd III lost thousands of pounds in them, and in the end his gambling losses led to his suicide.

Another legacy was the creation of two occupations—professional gamblers and cheats. Because cheats were detested, attracting such nicknames as rooks, wolves, and rogues in the eighteenth century, games began to be codified. Preeminent among the rule makers was Edmond Hoyle, who gave his name to the expression “according to Hoyle.”

English games, attitudes, and practices crossed the Atlantic, and Americans adopted them, but colonial gaming gained a character all its own. Gaming clubs never caught on in America because there weren’t enough people to support them in the few existing cities. Moreover, settlers did not typically hazard the large sums routinely wagered in Great Britain.

Even the wealthiest of planters did not have the deep pockets of British aristocrats, who could bet £15,000 without flinching. A frontier mentality accepted risk; it didn’t accept recklessness. Having created their own success, fewer men were willing to throw it away, and few colonists had the leisure for games. In short, in America gambling was a pastime, but not a vice.

Excessive gaming was, however. Stories abound from the 1700s of lost fortunes, ruined reputations, and plantations and indentured servants lost on the turn of a card. Virginian Landon Carter said, “No African is so great a slave” as a man obsessed with gambling.

Most Americans accepted Carter’s view and avoided Byrd’s fate, but gaming was a centerpiece of colonial life. Everybody did it—men, women, rich, poor, gentry, and slave. Like their English cousins, colonists bet on all sorts of things. They wagered on card games, like whist, piquet, cribbage, loo, put, and all-fours. Foreigners reported that card lovers could start a game after supper and play until dawn. Dice was a standard pastime, and betting on combative activities—bear baiting, cock fights, dog fights, dogs killing rats, target shooting, and wrestling matches—was popular.

Arguably, horse races were the most popular venue for gaming. As early as 1665, a permanent oval track stood at Hempstead Plain on Long Island, New York. Many consider this the birthplace of the horse racing industry. New York City eventually wanted something closer to home and built a track in lower Manhattan. Other sites popped up throughout the colonies, especially in the South. During the 1700s, well-known tracks operated in Alexandria, Annapolis, Fredericksburg, and Williamsburg. Prominent men took an interest in these tracks and the horses that ran on them. George Washington was a member of the Alexandria Jockey Club, as well as a club in Annapolis.

If tracks were not handy, fans conducted impromptu contests on public roads, a practice that became a public nuisance. In 1776, a Philadelphia grand jury warned about the dangers of these events: “Since the city has become so populous the usual custom of horse racing at fair in the Sassafras Street is very dangerous.”

The onset of the Revolutionary War did nothing to slow down gamblers. The Continental and British armies tossed dice and cards into the knapsacks and marched off to fight.

For commanders on both sides, gambling was a constant problem. Washington’s headquarters repeatedly issued orders trying to stop the wagering, as a typical directive from 1776 shows: “All officers, non-commissioned officers and soldiers are positively forbid playing at cards, or other games of chance. At this time of public distress, men may find enough to do, in the service of their God and their country, without abandoning themselves to vice and immorality.” Needless to say, the order’s effect was nil. Starving soldiers at Valley Forge rolled dice to win acorns to eat.

Washington might have gained some solace if he knew that the British army was facing the same problem. “The men are given to great gambling,” an English officer wrote, “and most shan’t have a coin left, even parting with their shirts at the dice and sundry card games.”

When the French appeared in American camps toward the war’s end, they brought their games with them. French officers invented a pastime similar to whist and dubbed it “Boston.” Boston migrated to New Orleans, where it enjoyed great popularity and became the namesake for the Boston Club, a private establishment that hosted many high-stakes contests over the years.

After Yorktown, United States citizens kept on gambling as they had when they were King George III’s subjects. Attitudes began to change, though, in the 1820s and 1830s. According to historian David Schwartz, author of the recently published book Roll the Bones: The History of Gambling, Americans began to rethink their love of games of chance. Citizens of the republic were becoming more sophisticated about money as the nation’s economy took off, growing used to handling large sums and more conservative with their funds. The religious revival of the Second Great Awakening launched abolitionist and temperance movements and helped define the productive and responsible citizen. To a lesser degree, it stimulated antigambling forces.

Opposition to gambling didn’t gain momentum until late in the nineteenth century, when laws began appearing that restricted gaming. So gambling went underground and pretty much stayed there until after World War I. During the 1920s, gambling gained some respectability with the rise of horse racing and betting at the track. State governments legitimized gambling further when they started lotteries in the 1960s and 1970s. In the 1990s, casinos took off and are today a multibillion-dollar national gaming industry.

Schwartz said that gambling is as American as apple pie and much older than the Mayflower, and it isn’t going away. It is something deep in the nation’s bones and reflected not only in games of chance but in the stock market and entrepreneurship. There is, he said, a straight line—a legacy—from the early settlers and the plantation grandees to today’s visitors to the Las Vegas Strip. None of these people mind taking a chance.

“Americans are more prone to take risks,” he said in an interview. “This nation was founded by people who left what was home and came over here. Clearly, they took a risk to get here.”

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed to the spring 2008 journal the story “The Truth about Betsy Ross.”