Fighting... Maybe for Freedom, but probably not

by Lloyd Dobyns

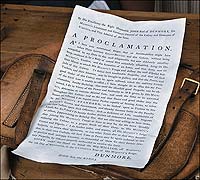

Governor Dunmore's proclamation, reproduced above, offered liberty to male slaves of rebels if they fought their masters.

Governor Dunmore promised freedom for male slaves of rebels who joined British forces, but the offer secured lasting liberty for few. From left, Emily James, Hope Smith, Janine Harris, and Greg James debate the risks and promises of Dunmore's proclamation.

Left to right, Jason Gordon, Richard Josey, with a copy of Dunmore's proclamation, and Willie Wright approach a redcoat, here Stuart Pittman, to join the British forces and gain freedom. The prospect of enslaved blacks fighting slaveholders was meant to frighten colonists.

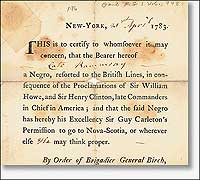

British General Samuel Birch issued certificates of freedom in New York to slaves who had joined the loyalist cause.

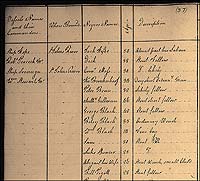

A 1783 list of blacks leaving New York on British ships, with their names, ages, status—slave or free—and destinations.

An early nineteenth-century watercolor of slaves harvesting sugarcane in Guadaloupe. Groups of defeated loyalists and their slaves fled the new republic and ended up in the West Indies, where few survived harsh life on the sugar plantations more than five years.

Slaves and free blacks fought for the Continentals and for the British during the Revolutionary War. At Monmouth, African Americans faced each other. That battle did not matter much, nor, at the end of the war, did it much matter for which side blacks bore arms, at least as it concerned their freedom.

A few American slaves for their service to the rebels were rewarded with liberty, but the operative word is few. For the most part, slaves who fought for the rebels remained the property of their masters. Anglo Americans were fighting for their freedom, but not for the freedom of their slaves. Those who sided with the British were told, more or less, that they were manumitted and would be given land and self-government. They had a better hope for freedom with the British than they had with Americans. But the British found it easier to promise liberty and land than to provide them. Slaves who departed with the redcoats when the conflict was over were in their new lands—Canada, England, Australia, and Sierra Leone—still treated much as they had been before.

The first wholesale promise from the British of freedom to slaves came just as the war was starting, in November 1775. The last royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, having fled Williamsburg for his safety first to HMS Fowey and then to HMS William, offered freedom to slaves and indentured servants "able and willing to bear arms" for the British. There was, however, a catch.

Dunmore's proclamation applied to slaves owned by rebels, not to slaves held by loyalists. His offer, the realization of an oft-repeated threat, was intended as much to terrify and punish rebels, and to furnish himself with more troops, as to help the slaves. Though slavery had been limited in England three years before—the Court of Kings Bench ruled in 1772 that slaves could not be taken out of the realm for sale—it was still legal and would be until 1834. Nevertheless, the rumor spread in the colonies that slaves had been freed in Britain, and it proved a powerful magnet for bondsmen.

Blacks who answered Dunmore's call suffered hunger, disease, and bombardment. Eight times as many died of sickness as did of battle wounds. After Yorktown, where for practical purposes, the fighting ended six years later, they found that their sacrifices would profit them little. Yorktown meant victory for the American cause, but spelled disaster for the enslaved.

The Continentals, including George Washington's troops, had such a mixture of black and white soldiers that a French staff officer referred to them as "speckled." American combat troops were not integrated as they were in the 1770s and 1780s until the Korean War 170 years later.

Free blacks and slaves often enlisted from New England. The First Rhode Island, a majority black unit, was well known. In the South, there was a congressionally approved plan—never realized—to arm, and eventually to free, three thousand slaves for service as a military unit for South Carolina and Georgia. Slaves sent to take the place of white owners were commonplace in the ranks, particularly in southern state militias. British commanders other than Dunmore encouraged rebel slaves to run away, and run away they did. The figures are guesstimates, but they are the best we have. Dunmore's promise attracted eight hundred to a thousand blacks, about a third of them women, though his proclamation applied only to males. In the South, perhaps eighty thousand to one hundred thousand slaves ran to British lines.

As the war proceeded, some rebel slaves were given to loyalist slave owners or shipped to English slave properties in the Caribbean or, for that matter, sent back to their rebel owners when they proved of little or no value to the British.

Thomas Jefferson said he lost thirty slaves and that Virginia lost thirty thousand, but historians like Australia's Cassandra Pybus suspect his figures. She suggests Jefferson got his Virginia tally by adding three zeros to his own loss, which he had inflated anyway. Whatever the numbers, the flight of slaves to the British speaks volumes about the institution of slavery in America. Taking the lowest numbers, look how many people would risk anything or everything for a chance, just a chance, to be free.

A chance was all most ever got.

At Yorktown, toward the end of the siege, the British drove blacks toward American lines in the hope they would spread smallpox among the Continental and French troops.

Some black Yorktown soldiers ran away. Some well enough to travel afoot made it to Philadelphia with French troops. A French officer wrote in his diary, "We gained a veritable harvest of domestics."

When defeated and paroled British officers, including Cornwallis, shipped back to New York aboard the HMS Boneta, some former slaves went with them on Cornwallis's orders. A handful got to New York without help. No matter how they made it, the slaves who escaped the white Americans at Yorktown were the exception.

Some loyalists and their slaves headed for East Florida, a British colony, sailing with the English from Charleston and Savannah. When Britain ceded East Florida to Spain, the Spanish governor gave the loyalists time to escape to avoid threats from Georgia and South Carolina, and they sailed again to the West Indies. The slaves remained slaves, often on sugar plantations where they would be worked to death in three to five years.

Some ships from the Deep South went to New York, however, and others, especially those with British wounded, made directly for home. Former slaves apparently were on them all. The largest force of redcoats remaining on the continent sequestered itself in New York City and, with loyalists and others under their protection, waited for peace and the chance to clear out.

To this point, free former slaves got their liberty less as the result of a British plan than through persistence and luck. For some who lingered with the redcoats, luck changed.

The Americans signed a preliminary treaty with the English in 1782, and, since it ended the fighting, slave owners now could and did go to New York to search for, argue with, or kidnap their runaways. The treaty's Article Seven prohibited the British from "carrying away any Negroes or other property" of Americans. General Sir Guy Carleton, British commander, and Brigadier Samuel Birch issued what amounted to certificates of freedom to the blacks in the city. British officers simply ignored Article Seven, and Carleton said "property" must surely mean at the time the treaty was signed, so the former slaves already in New York were not included.

To emphasize his point, Carleton sent a fleet with five thousand settlers to Nova Scotia, including white loyalists and black runaways. We do not know how many of either. Historian Simon Schama identifies the episode as "a revolutionary moment in the lives of African-Americans." It may also have been the high point in their search for freedom.

Nova Scotia, on the southeast coast of Canada, extends farther south than northern Maine and is all but surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean—basically, a flat almost-island first settled by the French in 1605. Scots came in 1621, hence the name of the place, Latin for New Scotland.

The refugees landed in a cold, sparsely settled, forested place, populated by Scots, Protestants from France, Switzerland, and Germany, and a few of the Mi'kmaq tribesmen who were the original residents. In no time at all, it was clear that whatever the American blacks were called, and whatever they had been promised, they would be treated like slaves and live a life not much better, and a lot colder, than they had lived in the American colonies.

They were segregated in housing enclaves and churches, economically oppressed, cheated, and lied to. When, infrequently, land was parceled out, theirs was the worst. One of the few ways to survive was to sign on for pitiful wages as indentured servants to white loyalists, some from the slave-owning South. The major difference was that the former slaves could and did sue for redress of wrongs in the Nova Scotia courts and sometimes won against whites. In Virginia, by contrast, blacks could not, in district courts, so much as testify against whites.

Across the Atlantic, London had about ten thousand blacks in its population, some slaves or former slaves of Englishmen, some escaped Americans, some former or current sailors on navy vessels or merchantmen, including slave ships. All but a few were desperate. Most could not find jobs, and charity depended not on the doles of the government but on the generosity of the parish in which you were born. Since the majority of blacks were not born in England, their needy would freeze or starve to death on the streets before they enjoyed charitable help. Many were reduced to begging or stealing, and stealing was a bad idea, since it was in those days a hanging offense. If you escaped the gallows, you were thrown in a private, overcrowded prison with no bed, no heat, little food, and less sanitation. Typhus, known in those days as "jail fever," was regular.

The American Revolution had caused dreadful overcrowding of the prisons. Before the war, English courts sentenced fifty thousand criminals a year to be transported, that is to say, sent to the colonies, as indentured servants for seven years. That outlet was denied them when the British colonies became America's states. Instead, in something of a reversal, a group of poorly educated, untrained expatriates had gone from the states to England, many of whom had no way to live but crime. America, once the solution, had become the problem.

The first thing the British tried was to transport criminals to Africa, but that did not work. Among the reasons was that Africa was close enough that the criminals transported would join a ship's crew and transport themselves back.

On May 13, 1787, eleven ships loaded with more than eight hundred convicts and two hundred guards set sail for Botany Bay in Australia, halfway around the earth, more than thirteen thousand miles away. Captain James Cook was the first European to reach the east coast and claimed it for England in 1770. At the time, fewer than four hundred thousand aborigines lived on the almost three million square miles of the continent. Australia would eventually make its European population from the convicts of Great Britain, including former American slaves.

A year before the fleet sailed for Australia, the humanitarian gift of free bread to the poor had shown that most of London's impoverished blacks were former Americans who had fought for the British. Free bread did little to relieve them. Concerned Londoners said the solution was to send the poor to a place where they would be independent and self-sufficient.

Considering how badly the settlement in Nova Scotia was doing, the Committee for the Relief of Black Poor suggested Sierra Leone on the African west coast. It was a curious idea since the country was at the heart of the African slave trade, and, by rumor, it had been considered for a penal colony before Botany Bay was picked.

Sierra Leone was a fiasco, an encyclopedia of how to do things wrong. In May 1787, 377 people went ashore at Frenchman's Bay. By March 1788, 130 were left, a mortality rate that rivals early Jamestown in Virginia. People also died in Nova Scotia, where the weather was cold and windy.

When they were given a chance to relocate to Sierra Leone, twelve hundred of them, perhaps a third of the colony, sailed on fifteen British ships. They were promised self-government and no racial discrimination. The promises were empty. The settlement failed. The white officers of the Sierra Leone Company in London blamed it on the former slaves' curious and radical ideas of freedom. They were the same curious and radical ideas that had driven the American Revolution.

Descendants of the former slaves still live in Sierra Leone, Australia, and Nova Scotia.

One thing more. When British officers sent former slaves to Nova Scotia despite Article Seven, it had a consequence no one anticipated. The final peace treaty required that Americans pay their legitimate debts to English merchants, which were considerable. Some Americans refused, saying that if the British had not illegally carried away their property, the slaves could have been sold to satisfy those obligations. One of them was Thomas Jefferson.

View a clip of black soldiers in the Revolution

from Colonial Williamsburg's 2006 Electronic Field Trip "Yorktown."

Clip 1

Clip 1Small - Quicktime (912kb)

Small - Windows Media Player (900kb)

Large - Quicktime (1.5Mb)

Large - Windows Media Player (1.7Mb)

Clip 2

Clip 2Small - Quicktime (1.6Mb)

Small - Windows Media Player (1.6Mb)

Large - Quicktime (3.2Mb)

Large - Windows Media Player (3.1Mb)

Lloyd Dobyns, former NBC News television correspondent and journalism professor, contributed to the autumn 2006 journal an article on Colonial Williamsburg's Revolutionary City.

Suggestions for further reading:

- David Brion Davis, Inhuman Bondage (New York, 2006).

- John Iliffe, Africans (Cambridge, 1995).

- Gary B. Nash, The Forgotten Fifth (Cambridge, 2006).

- Cassandra Pybus, Epic Journeys of Freedom (Boston, 2006).

- Simon Schama, Rough Crossings (New York, 2006).