Revolutionary City

A Colonial Adventure

Text by Lloyd Dobyns

Photography by Dave Doody

Emma Cross, left, and Brooke Barrows catch the Revolutionary City from the second floor of the millinery shop.

Interpreter Ken Johnston rallies the crowd in the name of fair liberty, the patriot cause, and independence from Great Britain.

Author Dobyns with Ron Carnegie as George Washington, behind them, Mark Schneider, as Lafayette, and Scott New—three of the mighty and the ordinary that guests encounter.

Greg James, left, Cash Arehart, and Art Johnson prepare a liberty pole—with its bag of feathers and bucket of tar—for reluctant loyalists.

Interpreter Donna Wolf bids husband Scott New goodbye as he heads off to Charleston to battle the British; Alex Morse looks on.

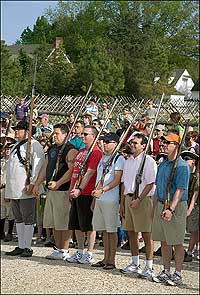

Ken Briner drills guest militiamen as the soldier-citizens train to battle the world's finest professional army.

Wolf, her husband long a British captive, pleads for work from Chris Allen during the desperate times of war, when work, money, and food were scarce.

You can have the American strategy for the 1781 siege of Yorktown explained to you in the middle of Williamsburg's Duke of Gloucester Street by General George Washington and the Marquis de Lafayette. It happens every other day, and you'll be pleased to know that Washington's strategic analysis is correct. Here's how he sees it: General Charles Lord Cornwallis, commander of British forces in Virginia, has his back to the York River at the end of a narrow peninsula, his escape by land or water is cut off, he is outnumbered by French and Continental troops, and he is going to get his booty kicked. The Americans and French will win the Revolutionary War. Huzzah! Or "hooray" in twenty-first-century terms.

Oh, and Generals Washington and Lafayette will answer your questions. That's how I know Washington is astride Nelson, the horse given to him by Thomas Nelson Jr., the third governor of Virginia, who will command the Virginia militia at Yorktown.

Welcome to the penultimate scene in the Revolutionary City, the street theater in a part of Colonial Williamsburg's Historic Area that started this spring. It resembles nothing so much as the 1950s You Are There television series on CBS with Walter Cronkite. The series took one major, historic event and reported it for a half-hour as if it had happened that day. The Revolutionary City covers in two afternoon performances of about two-and-a-half hours each not a single event but many events from 1774 to 1781 that led to American independence. To that extent, it is what you could call hurry-up history, but done with energy and enthusiasm and a bit of difference.

The facts are clear. Virginia's royal government collapsed between May 1774 and May 1776, and the events of that time are the first day's presentation. The second day starts with the Declaration of Independence being read aloud in Williamsburg in July 1776, then goes for five years of war until Continental forces march from Williamsburg to Yorktown in September 1781. That was the decisive final siege of the revolution, though the war dragged on for two more years, until a peace treaty was negotiated in Paris.

If the facts are clear, how and why the Revolutionary War happened when it did, where it did, are not so clear, and that is what the Revolutionary City wants to explain. Colonial Williamsburg is especially qualified as the theater for the explanation. There are 301 acres of restored and reconstructed buildings that look as they did in that time. Rex Ellis, vice president of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Historic Area, says, "We have the best three-dimensional theater in the country. We have the country's largest outdoor history museum."

You will recognize some of the names from Williamsburg in that seven-year period, but many of them you will not. For instance, carpenter Alexander Hoy and his spouse, Barbara, do not appear in standard history books, certainly not in any I studied, but they are as important to explaining the Revolutionary War as is Washington. In one scene the carpenter and his wife argue about his joining the militia for an enlistment bonus, money the family desperately needs. The next time you see her, she's returned from Charleston, where she's been searching for her missing husband, who may be on a British prisoner-of-war ship or may be dead. In truth, there's not much difference. Either way, the enlistment money is gone, so is her husband, and she is reduced to charity. Hello, welcome to the Revolutionary War as it was.

The Revolutionary City is as much about ordinary citizens—men and women—and slaves as it is about the people history names and remembers, as much about price gouging and begging and not knowing what to do as it is about battles and bands and glory. Benedict Arnold is an American hero in one scene. An actor announces the news of his victory at Saratoga and leads the three cheers from the guests. A few scenes later, Arnold, now a British-bought traitor, takes Williamsburg and raises the British flag over the Capitol. The Revolutionary City is war with all the warts and twists.

It is much like the movie and stage melodramas where you get to cheer the hero and boo the villain, which gets you involved. Remember this is street theater, and the guests cheer and boo with enthusiasm. You are outside, moving back and forth at the east end of Duke of Gloucester Street, watching eighteenth-century scenes play out against eighteenth-century backdrops. It helps that you already know how the war ends, so you don't have the eighteenth-century heartache of trying to figure out which side to support, although it is still a bit shocking to hear a Virginian of that period yell, "God bless you, Lord Dunmore" to the last royal governor. God bless you, Lord Dunmore? Well, 25–30 percent of Virginians then supported the monarchy.

If you were a slave, would you believe Lord Dunmore when he promised you freedom if you fought for the British? Many blacks fighting for the British, including all of those who survived at Yorktown, will be driven back into slavery, but some make it to Nova Scotia, Britain, Australia, France, and Sierra Leone. They were no longer enslaved; they were still impoverished. Many slaves and free blacks fought for the American patriots, though few slaves won their freedom. Part of the Revolutionary City story is the reaction of slaves to the war, and the white colonists who insisted on freedom from Britain but who did not insist on freedom for blacks from slavery. It would take another eighty years and another war to extend freedom to slaves, and in both wars, families were torn apart.

In the Revolutionary City, Arianna Randolph argues with daughter Suzanne about returning to England because of her husband's loyalty to the crown. John Randolph and family did, in fact, return to England, but their son stayed in the colonies as an aide to Washington, and brother Peyton Randolph was one of the Revolution's guiding lights, the president of the first and second Continental Congresses.

The Revolutionary City is history, but it is not staid; you will learn a lot, but you won't be bored, and, best of all, there is no quiz. The historic scenes are separated by fun as eighteenth-century characters mingle with the twenty-first-century crowds. Two women in street-length gowns—you may recognize Arianna and Suzanne Randolph—teach a half-dozen couples wearing shorts and blue jeans a simple eighteenth-century dance on the sidewalk to the music of a walking-stick flute. A what? A flute in a cane, perhaps not an ordinary eighteenth-century musical instrument, but a walking-stick flute has survived in Williamsburg. It is a pleasant instrument.

I got into a discussion with a woman dressed partially in men's clothes, including a three-cornered hat, who wanted to work as a servant for me, and she did not much mind what the work was. That, too, was a reality of the Revolutionary War. Prices for everything had been driven through the roof, and people were desperate for any job. She and I got into our unscripted scene—she was better at it than I—and we attracted a bit of a crowd and a couple of photographers. It was fun, and, of course, I thought of all the clever things I should have said after she was gone. Some things, I am sure, do not change with time.

Later, there was an English army captain captured in battle who had two school-age boys from Massachusetts, clinging to their mother's hands, fascinated, but not altogether sure they should trust a British officer, and especially not a haughty, egotistical, snobbish one. When the prisoner exchange came, the English captain said, he would be traded for an American colonel or maybe even a general, since that is what he was worth, he thought. The boys didn't say what they thought he was worth.

Of course, the Americans weren't all swell people either, and their excesses were severe and unpleasant. A Liberty Pole on Duke of Gloucester Street holds tar and feathers to be used on enemies. And who was an enemy? Anyone who was not a vat-dipped, double-dyed, 110 percent patriot. While not much is made of American excesses in standard American histories, among the patriotic revolutionaries were vandals and thugs. The Revolutionary City does not focus on it, but the downside of patriotism is not ignored. As you might suspect, with runaway inflation, the collapse of Virginia's economy, and an unknown and unknowable future, some merchants could not resist the temptation to hoard, and drive up prices. The court they face is the court of public opinion.

If you think about it, nothing about the Revolutionary War is pleasant, except that the Americans won, and that was more the intervention and planning of the French than the strategic concepts of the Americans. Left to our own devices and our own forces back then, we might still be British colonials even now.

Best not to dwell on that.

One of the things that contribute to the festive atmosphere of the Revolutionary City is the Fifes and Drums, who march on Duke of Gloucester both days and always attract a crowd of followers. There is something about martial music that inspires a parade. It is easy to forget that the reason for the Fifes and Drums was only partially as a musical unit and more to send orders to the troops, who could hear drumbeats from a distance. Cornwallis signaled his surrender at Yorktown by ordering a drummer boy to the top of a British parapet to beat the signal for "parley."

Three weeks before that surrender then, on the second day of the Revolutionary City now, guests are recruited to march as Continental soldiers behind the Fifes and Drums, heading to the Courthouse to listen to Washington, then about to leave for Yorktown and the decisive battle of the war. Since the guest-soldiers have never had a chance to drill together, you think they are about as inept as the militia must have been. The modern march is more for the amusement and participation of guests than it is for historical accuracy; five years into the war, the militia under Washington and Lafayette was an experienced, well-drilled military combat force. But the French in beautiful white uniforms—not represented in the Revolutionary City—made everyone else look like stumblebums anyway.

The French, the British, the Hessians were professional, standing armies. The Continentals, or Americans, were drawn from nonprofessional militias—recruited, armed, and deployed by their state governments. At that time, there was no federal government, although the thirteen states had confederated. Winning at Yorktown in 1781 was a small part, perhaps the easiest part of what Americans had to do to achieve independence, to create a stable form of popular government, a form that had rarely been seen.

Do the people who attend the Revolutionary City understand what they see? Certainly they do, although many of them will admit that they don't know their history as well as they might, and they are particularly shaky on the history of women and slaves. As a man from Massachusetts with his wife and two daughters told me, "I know all about Lexington and Concord and the Boston Tea Party, but I didn't know this."

The Revolutionary City, Ellis says, "focuses on that period from 1774 to 1781 when we believe the most dynamic, engaging, important story we have to tell here at Colonial Williamsburg took place. We believe that the story of how we became Americans, how we moved from a British monarchy to an American democracy is that story that has regional, national, and international repercussions...I think what we're trying to do is challenge everyone to think about what took place, to think about the American Revolution."

Here is what they might think about. It is in Akhil Reed Amar's book America's Constitution: A Biography:

In 1787, democratic self-government existed almost nowhere on earth. Kings, emperors, czars, princes, sultans, moguls, feudal lords, and tribal chiefs held sway across the globe...Before the American Revolution, no people ever explicitly voted on their own written constitution...America's Founding gave the world more democracy than the planet had thus far witnessed.

That's what happened here. That's what the Revolutionary City is about. You can't get Washington and Lafayette to explain that to you on Duke of Gloucester Street. In September 1781, they did not know it. No one did. Yet.

Lloyd Dobyns is a retired NBC News television correspondent, a winner of the Peabody, Dupont-Columbia, and Humanitas awards, a former university professor, and a member of the Virginia Communications Hall of Fame. As an actor, he portrayed John Adams in the The Common Glory at Lake Matoaka Amphitheater in Williamsburg in 1955. This is Dobyns's first feature article for the journal.

For further information:

- A Look at the Revolutionary City in the Spring 2006 Journal