Colonial Foodways

text by Ed Crews

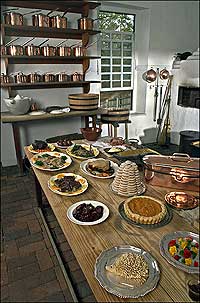

From left, Jim Gay, Barbara Ball, Frank Clark, Rob Brantley, Dennis Cotner, and Susan Holler of Colonial Williamsburg's foodways program set out a grand meal in the Governor's Palace kitchen. In front, beef, chicken, and fish dishes anchor a meal that includes vegetables, baked goods, and deserts.

Principal cook William Sparrow began his day early at the Governor's Palace in Williamsburg. He went to the kitchen as soon as he had light to see to work. He couldn't waste a minute. Servants had to be awakened. Fires required stoking. The market opened early, and Sparrow hurried to it as soon as he could to buy the day's groceries. He created a menu and had the staff prepare and cook food. Everybody focused on delivering dinner, the day's largest and most elaborate meal, to eager visitors at about 2 p.m. Cleanup followed. Probably, Sparrow then could catch his breath. After all, as usual, supper and tomorrow's breakfast would be leftovers from the afternoon meal.

The six members of Colonial Williamsburg's foodways staff work at a less demanding pace than Sparrow. But like him they use eighteenth-century kitchenware, recipes, and ingredients to make the same meals that graced the tables of the wealthy and powerful in colonial Virginia. Specialist Dennis Cotner, journeyman Robert Brantley, and apprentices Barbara Ball, James Gay, and Susan Holler teach guests about colonial food processing, cooking and consumption. The team's culinary achievements range from roast pigeon to a ragout of cucumbers, fried ox tongue, mince pies, and syllabub, a sweet, frothy, alcohol-laden dessert. Guests can watch them preparing these and other colonial specialties in the Historic Area at the kitchens for the Governor's Palace and the Peyton Randolph House, places to accommodate a crowd, to demonstrate cooking techniques, and to exhibit finished dishes.

The foodways team prepares dishes served to the colony's upper class because so much historical information about their culinary life is available, said Frank Clark, foodways supervisor and Colonial Williamsburg's first journeyman cook. Historians know far less about food practices of people further down the social scale, but cookbooks, documents, kitchen inventories, and archaeological research provide a detailed picture about how the governor and the gentry dined. For example, Sparrow's account book survives, detailing his marketing. With this information, Williamsburg interpreters use the same ingredients on the same days Sparrow did when he worked at the Palace in 1769 and 1770.

Modern Americans have a few things in common with the dining habits of the colonial upper crust. Basic cooking techniques haven't changed. Colonial cooks fried, roasted, baked, and boiled. They used many of the same foodstuffs found in today's groceries: beef, lamb, pork, chicken, fish, vegetables, and baked goods. Then as now, coffee, tea, and chocolate were popular beverages.

Beyond these common roots, though, little was the same as it is today. Food preparation and presentation were different. So were diner's tastes, customs, and expectations.

To start, eighteenth-century cooks could serve only food that was in season. Fresh fruits and vegetables were not available year round. Colonial Virginians could preserve some foods for the long term, typically by smoking or salting. Short-term preservation, say a few days, was impossible without refrigeration.

Anyone who wanted chicken for dinner got the bird early in morning, killed it, cleaned it—which included plucking—and cooked it. Colonists ate the leftovers at supper and breakfast before they could spoil. Dining on a grand scale was a logistical challenge. The English nobility kept kitchen staffs filled with specialists because of this. King George II employed 200 cooks at one time.

Cooking and baking required the ability to use a wood fire. Nobody employed kitchen thermometers. So successful cooking meant gauging and using wood heat accurately and carefully.

"Cooking with wood isn't any more difficult than cooking with any other fuel. Heat is heat regardless of the source. However, with wood, the cook has to be more patient and plan ahead," Gay said. "You have to generate hot coals, which when piled up, become your burners. The best fuel to use is well-seasoned hardwood, which burns hotter and longer than softwood. The cook has to be able to 'read' the fire and know which coals are the hottest. You judge heat by color and brightness, much like a blacksmith looks at hot iron. Yellow heat is hotter than orange, which is hotter than red. You also have to remember that once you take hot coals out of the fire, you have to put more wood on it."

Cooks also approached seasoning differently than their twenty-first-century counterparts because eighteenth-century tastes were different. By today's standards, colonial fare offered too much grease, too much meat, too much seasoning, and too much sweetener. Diners liked meat and lots of it. They considered animal organs, like hearts and brains, tasty delicacies. Cooks used sugar, cinnamon, and nutmeg liberally. Raw fruits and vegetables were considered unappetizing. So the kitchen help usually cooked them. Sweet drinks prevailed, too. Dry wines were not popular. Madeira, a sweet wine fortified with brandy, was. Cocktails didn't exist, but alcohol-rich punches did.

Food presentation was different. The main meal, dinner, was served midafternoon. Formal meals had two or three courses. Meat dishes often came to the table with the animal's head and feet attached. The upper class ate little bread. Instead, they might use a roll to maneuver food on a plate and sop up gravy and sauce.

Anybody aspiring to cook for the upper class in America or England learned the art through an apprenticeship. This meant finding a skilled cook to serve as instructor. For part of the eighteenth century, it also meant learning to fix French cuisine. Brought to England by Charles II, French food had a limited but enthusiastic following in the nobility. This style relied heavily on sauces and dishes requiring multiple steps in preparation. In Virginia, a governor might have a European-trained head cook. The gentry probably didn't, although they might encourage their cooks to learn European techniques.

Not everybody approved of Gallic cuisine. People lower in society liked their food simpler. That explains why the period's most popular cookbook was Hannah Glasse's The Art of Cooking Made Plain and Easy for Housewives and Maids, published in 1745

Almost everybody in the 1700s could cook, Brantley said: "Guests are surprised by who was actually doing the cooking. They automatically assume that only black females did cooking in the eighteenth-century homes. Some guests are shocked when they learn that many people—men, women, black, white, rich, and poor—learned to cook on some level."

Governor Dunmore cooked for himself on trips to the frontier. Lawyer George Wythe did the same, traveling to meetings of Congress in Philadelphia.

The Colonial Williamsburg apprentice program covers a body of knowledge from butchering to frying, broiling, roasting, and baking and making sauces, soups, and creams. Special programs focus on beer brewing, chocolate making, and hog butchering.

"Everybody is interested in food," Clark said. "At one point, everybody has tried to cook. So we have an instant connection with people the moment they step in the kitchen. We reach their hearts through their stomachs."

Ed Crews is contributing a series of stories on Colonial Williamsburg trades. His story "Spies and Scouts," on Revolutionary War intelligence, appeared in the summer 2004 issue. Read his article "Cast in the Colonial Mold" from the winter 2003-04 journal.