St. George Tucker House

Block 29, Building 2

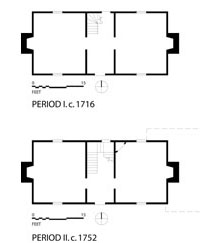

Standing on the north side of Market Square, the large central greensward that bisects the Duke of Gloucester Street, the St. George Tucker House is one of the most complex eighteenth-century structures to survive in Williamsburg. With its elongated plan, varying roofline, and many gables, the dwelling is perhaps the city's most picturesque building, which is only enhanced by the two large plantings of overgrown boxwoods that flank its east and west sides. Unlike other colonial dwellings in town, the house has a sprawling, horizontal mass, which developed as the result of a series of late-eighteenth-century additions and mid-nineteenth century alterations. The core of the building dates from the early days of Williamsburg when theatrical entrepreneur William Levingston erected a one-story, center-passage dwelling that measured forty feet by eighteen feet. Levingston's house stood on a plot a land facing Palace Street a few hundred feet from its present location.1

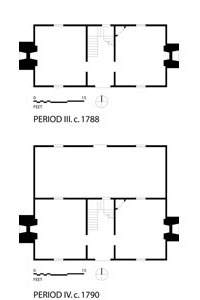

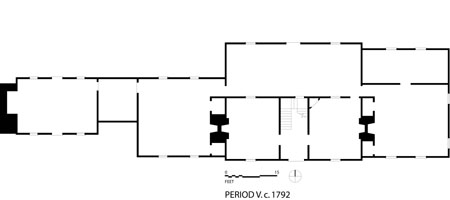

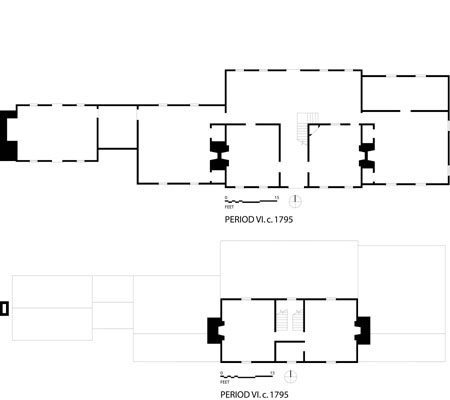

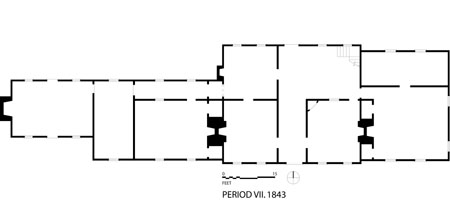

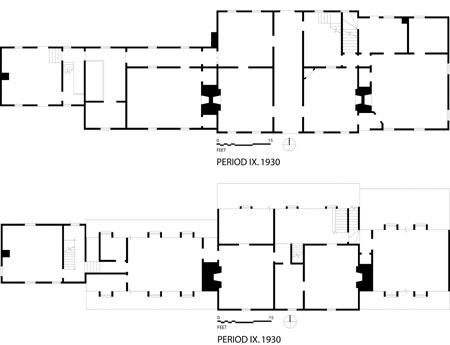

At the end of the eighteenth century, jurist St. George Tucker moved this small dwelling so that it faced Market Square and used it as the nucleus of a greatly expanded residence. Between 1788 and 1795 he added a second story, built the shed on the north side, constructed wings on the east and west, and erected a kitchen and covered way that was connected to the west wing. His son Nathaniel Beverley Tucker made numerous alterations in the early 1840s, changing the circulation pattern of the house and raising the roofs of the rear shed and side wings. Finally in 1930-31 architects Perry, Shaw and Hepburn reworked the building for the Coleman family, Tucker descendants, by adding several new partitions, stairs, and trimmed the entire dwelling with colonial details, turning the ensemble into a curious mixture of colonial and colonial revival spaces.

St. George Tucker, known in his day as "the American Blackstone" for his knowledge of the laws, was born at Port Royal, Bermuda in 1752 and came to Virginia in 1771 to enroll at the College of William and Mary. He studied law under George Wythe, and after service in the American Revolution, he succeeded Wythe as professor of law in 1790, which prompted his dramatic alterations to the house. Tucker sat as a judge on the Virginia General Court from 1785 to 1802 and served on the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals from 1803 to 1811. In 1813 he was appointed a judge of the United States District Court, a position he retained until his death in 1827. Nathaniel Beverley Tucker followed his father's career in the law and teaching. He inherited the house following the death of his stepmother and made numerous changes to it in the early 1840s.

The St. George Tucker House is probably the best-documented house in Williamsburg. The Tucker family preserved most of the contracts and accounts of the work that transformed the modest original core into a substantial dwelling in the late eighteenth century. As a result, the names of the craftsmen who manufactured the bricks, fabricated the doors and windows, and installed most of the surviving woodwork are known along with the cost of every item. The carpenter who moved and reconstructed the old house was John Saunders who, along with William Piggett, undertook the woodwork of the numerous additions. Bricklayer Humphrey Harwood, followed by his son William who took over the work on his father's death in 1789, supervised the masonry work on the new site, which included the construction of raised cellar foundations, two massive chimneys, and brick fill inserted between the framing members. One of the rarest of survivors is a contract between Tucker and Jeremiah Satterwhite concerning the painting of the house in 1798.

Paint investigation verified that Satterwhite applied the colors Tucker specified, so the various parts of the exterior are once more painted straw color or yellow ochre, white, and the brickwork covered with a dark red approaching the color of chocolate. The roof shingles were painted Spanish brown.

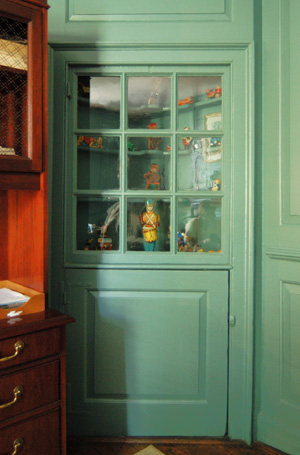

Tucker's additions to the old core of the house produced a plan that created several zones of activities from the more private functions on the east or right hand side to more public ones on the west side of the house. On the main floor, the east wing consisted of the main bedchamber and a series of dressing rooms. Next to it was Tucker's study, the present paneled room whose woodwork mainly dates from the 1750s remodeling by former owner, the apothecary George Gilmer.

The glazed china closet or buffet standing in the northwest corner of the room was installed by Gilmer to accommodate a new set of dishes imported from Bristol in 1752.

The center passage divides the public from the private realm and leads to a large unheated back room known in Tucker's day as the shed, which also housed the staircase to the two, second-floor chambers.

A staircase rose along the south wall of the shed to a landing and then turned at a right angle back to the front passage where it rose to the second floor. (The present staircase in the east corner contains parts of the 1750s staircase installed by George Gilmer but was not placed into this position until Nathaniel Tucker raised the shed roof, the roofs of the two wings, and added dormers in the 1840s. The staircase in the west corner was installed in the early 1930s and did not exist in the Tucker period.) The room was more than a circulation space. The Tuckers used it as a large sitting room, where they could look through the four large windows that lit the north wall into their extensive garden parterres.

The Tuckers entertained guests in the rooms west of the center passage. A small parlor opened off the passage opposite Tucker's study. A door on the north wall of this room led into the back shed. Visitors walked through a small passage at the west end of the shed to reach the large dining room in the west wing. The dining room was originally subdivided by a passage on the north side that allowed uninterrupted access from the back shed to the covered way and kitchen to the west. On the second floor in the center section, Tucker erected two bedrooms and a dressing room for his many children. The rest of the upstairs was uninhabited attic space until Nathaniel Beverley Tucker raised the roofs of the two wings and made other substantial alterations in the early 1840s.

The cellar space beneath the main house contained storage rooms with paved brick floors, which may have also served on occasion as additional bedchambers for the large household.

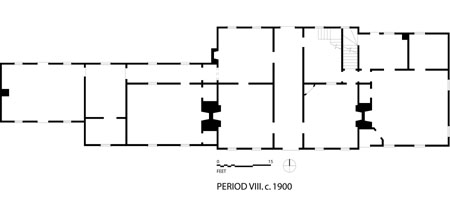

In the late nineteenth century, the large house was subdivided into two residences as a new doorway was added to the front of the east wing for separate entrance and a new staircase added to provided access to the bedchamber above. Other alterations made during this time included the raising of the old west kitchen to two full stories. The house was restored by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation as a residence for the Colemans in 1930-1931.

The alterations were intended to make the house habitable for the family and create an exterior that was compatible with the colonial buildings surrounding the site. As a result many of the Greek revival alterations made by Nathaniel Beverley Tucker in the early 1840s were not demolished but merely retrimmed in colonial details. For example, the roofline and dormers that Tucker has raised to accommodate bedrooms in the two wings were left in place. During the renovations, the present kitchen and covered way (expanded slightly from its original width) were rebuilt including the much-admired chimney on the west end of the kitchen. In the main house, the original brick fill was removed during the restoration but much of it was reinstalled. The central chimneys were rebuilt above the roofline. All cornices on the old parts of the house, except that on the north side of the west wing, are original and were repaired rather than replaced. Many of the weatherboards, especially on the center section, are original, as are the endboards and bargeboards. All the shutters were renewed, but the front door is carpenter William Piggett's handiwork of the early 1790s. Among the most notable original features in Tucker's remodeling were a series of triple-hung sash windows that lit most of the main floor rooms and were among the earliest examples of this form in Virginia, similar in form to those installed by Tucker's friend Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. Unfortunately, these sash were removed during the renovation of the building in the early 1930s under the mistaken notion that they were later features.

Most of the interior had been retrimmed in the Greek revival period of the early 1840s. This was replaced by colonial-inspired trim with a number of fanciful additions including an arch and wainscoting in the center passage. However, much of the paneling and corner cabinet in Tucker's parlor survived from Gilmer's 1750s remodeling and parts of the staircase in the northeast corner of the shed dates from this period as well. Floors in the old parts of the house generally are original though there has been much patching over the years. In 1995 the building underwent some repairs with the addition of new HVAC systems to turn the building into a hospitality house with second-story offices. At the same time, archaeological investigations of Tucker's rear yard revealed that the jurist and his family took great pleasure in ornamental gardening. The area behind the main section of the house was covered with extensive parterres with orchards located beyond at the north end of the Tucker property.

Endnotes:

- Excavations in 1931 revealed the foundations. Tree-ring dating indicates that the oak trees were cut for the house frame after the growing season of 1718. Herman J. Heikkenen, "The Last Year of Tree Growth for Selected Timbers within the St. George Tucker House, Period I, as Derived by Key-Year Dendrochronology," Dendrochronology, Inc., March, 1995. For a detailed architectural account of the Tucker House, see Carl Lounsbury, Mark R. Wenger, and Roberta Laynor, "The St. George Tucker House: An Architectural Analysis," 2000.

Carl Lounsbury is an architectural historian in the Department of Architectural and Archaeological Research. This article is part of a series writtten in 2004.