Timson House

Block 30-1, Building 4

Standing on the northwest corner of Prince George and Nassau Streets, the Timson House is one of the earliest structures in Williamsburg.1 In 1714 William Timson, a prosperous York County planter, acquired lot number 323 from the trustees of the city of Williamsburg and constructed a one-story frame house in 1716.2 In 1717 Timson sold the house and lot to tailor James Shields. The Shields family continued to live in the house until 1745 when it was sold to carpenter James Wray. The Wray family rented the house to a series of tenants until the time of the Revolution.

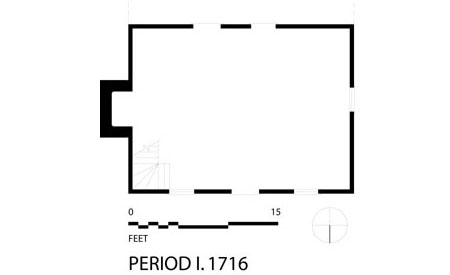

The Timson House is a rare example of a modest, one-room house dating from the early eighteenth century. Contemporaneous with the nearby Brush and Levingston Houses (the latter now embedded in the St. George Tucker House), the dwelling is much more representative of the types of structures inhabited by most Virginians in the colonial period in terms of its size compared to the most houses in Williamsburg. The original building erected in 1716 consisted of the central section of the present structure, measuring 22-½ feet wide by 17 feet deep. A full cellar stood beneath the house from the beginning. Entrance into the ground-floor room was through a central door between the present front two windows facing Prince George Street. Although the present chimney is a nineteenth-century replacement, an earlier fireplace warmed the ground-floor room in the same location. Next to this chimney in the southwest corner, a small winding staircase rose to the second-floor bedchamber, a position that was common in many Virginia houses in the colonial period.

On the back or north wall, a four-foot jetty or overhang was constructed. It is unclear why Timson's craftsmen built the jetty. It may have provided a sheltered workspace at the back of the house if this jettied space remained opened, or it may have been the means of providing more useable floor space above stairs. Two doorframes were discovered embedded in this back wall whose presence is puzzling. Generally, the appearance of two doors in such a location would signal the division of the front or back spaces into two separate areas. It seems unlikely that the main room was subdivided into two rooms. A more likely possibility is that the jettied area beyond the north wall may have been enclosed and subdivided in some manner. There is no evidence in the surviving framing for such a subdivision and the absence of a wall plate in the eaves would argue against a small four-foot deep enclosure. In lieu of an enclosure in line with the eaves of the jetty, it is possible that a deeper back room may have been built, evidence for the foundations of which may still survive beneath the ground.

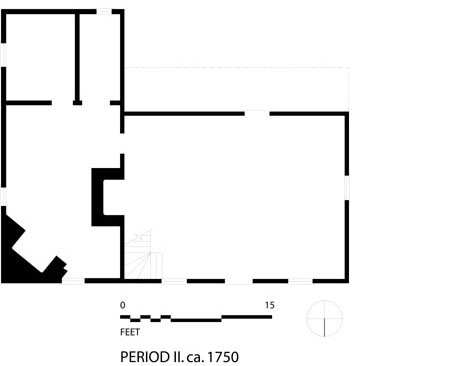

Sometime after the middle of the eighteenth century, the one-story west shed was added to the house. Archaeological evidence suggests that the addition was probably constructed by carpenter James Wray or his son during their ownership of the property between 1745 and 1772. This wing measures 12 feet in width and 27 feet deep and was subdivided into at least three spaces. A southeast corner fireplace heated the front room. Behind this room, which may have been used as a parlor or bedchamber, were two, smaller unheated rooms of unequal size. The addition of the west shed rooms prompted a small change in the main part of the house.

If the original section had not been plastered already, it was certainly completed with the construction of the addition. The main room was also painted by this time as traces of Spanish brown and darker brown paint can be found on the exposed part of the plate and around the eastern back door.

The addition of the west shed also prompted the sealing of the western back door. A pedimented porch was added to the front of the house at this time. Scars in the fascia board of the cornice and in the uppermost beaded weatherboard between the two front windows outline its shape.

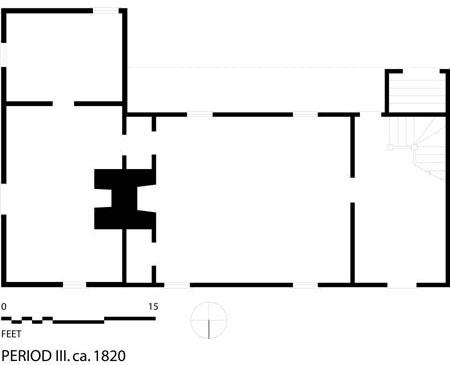

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, the house passed into the Ferguson family who owned the building until the early 1840s. They made substantial changes in the second decade of the nineteenth century with the construction of the nine-foot wide stair passage on the east end of the house, the fabrication of a new chimney, and the addition or alteration of several apertures. These alterations provided a more commodious access to the second floor, a better arrangement of ground-floor rooms, and a more formal entrance to the house.

With the construction of a new entrance in the stair passage, the old front doorway was closed and plastered over on the inside and weatherboarded on the outside. This addition fundamentally transformed the circulation pattern of the house, making it at once more private and segregated. Entrance into the house was through the passage first before access was gained to the main room, a measure of privacy previously unavailable when the front door opened directly into it. The rear door was blocked as well and two windows constructed on this wall opposite the front ones, which more than compensated for the loss of the window on the east gable end. With the removal of the original staircase from the southwest corner, communication between ground and upper story moved out of the room to the new stair passage. However, the room was not entirely private as it still provided the only access to the mid-eighteenth-century shed rooms to the west.

The old chimney, which had serviced the original house, was taken down along with the corner chimney that had been constructed in the southwest corner of the mid-eighteenth century shed addition. In their place, a new chimney was built which contained four fireplaces: one in the cellar (which still retains its cooking crane), one in the ground-floor room of the original house (the principal entertaining room), one backing against it in the shed addition, and one in the bedchamber on the second floor in the original section.

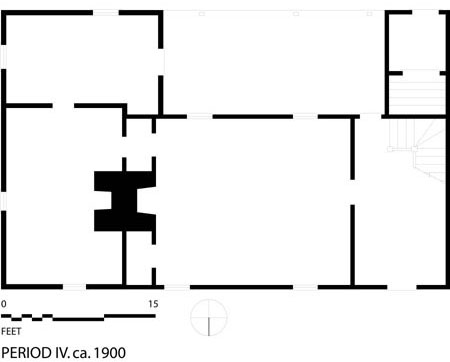

After the Ferguson ownership, the Timson House passed through many hands in the second half of the nineteenth century and the first three decades of the twentieth century. Purchased by the Rev. W. A. R. Goodwin in the late 1930s, the house had a substantial addition made to the rear of the building and as well as renovations to the older section. In 1969 the house was sold to Colonial Williamsburg and in 1996 it was thoroughly renovated with new HVAC systems.

Endnotes:

- For a more detailed study of the house, see Carl Lounsbury, "An Architectural History of the Timson House," 2003, Rockefeller Library.

- In 1990 Dr. Herman J. Heikkenen of Dendrochronology, Inc. examined the original framing of the Timson House and determined that the oak sleepers and tulip poplar rafter were felled after the 1715 growing season. This analysis implies that Timson constructed the house the following year.

Carl Lounsbury is an architectural historian in the Department of Architectural and Archaeological Research. This article is part of a series writtten in 2004.