Lael White

Illustration of militias on parade at the centennial celebration in Yorktown, for which the C&O railroad extension line was built.

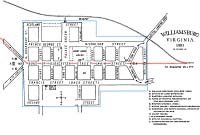

A view down Main Street, better known as Duke of Gloucester Street, where train tracks for the Peninsula Extension once ran.

The Duke of Gloucester Street Special

by Will Molineux

Sledgehammer-swinging railroad workers laid tracks down the length of Duke of Gloucester Street in 1881—to the exhilaration, and the annoyance, of Williamsburg's citizenry. The laboring gangs came, robustly and hastily, from the west, down the stage road from Richmond, past Robert Bright’s brick farmhouse, and turned east where the College of William and Mary’s Main Building, fire damaged during the Civil War, was shuttered, its classrooms empty. Past old Bruton Church, and the Courthouse raised in 1770, and the 1715 Powder Magazine—then a horse stable—and across the foundation stones of the vanished Capitol, put down in 1701.

They moved, repetitiously, along on the level, ready-made roadbed, a locomotive pushing before it flatbed cars loaded with creosoted wooden ties, steel rails, and spikes, until they reached a meadow a little more than a mile east of town. There they met head-on rails laid westward from the James River waterfront at Newport News. At 2 o'clock on October 16, a Sunday afternoon, the superintendent of construction drove the unifying spike as 600 workers burst into what was described as “vociferous applause” that made “the welkin ring.” The supply train steamed on to Newport News.

It is hard to imagine that such an undertaking as completing a railroad—surely witnessed by everyone in Williamsburg and from farms all around—was so little documented, especially since it disrupted the community’s main thoroughfare. Brief stories appeared in Richmond newspapers days later, Wednesday, October 19, the 100th anniversary of Cornwallis’s surrender at Yorktown. No photographs have been found to confirm it, but by that time, soot-spewing locomotives had chugged through Williamsburg tugging a few passenger coaches filled with militiamen eager to parade at Yorktown before President Chester A. Arthur during the nation’s centennial celebration.

The Richmond Dispatch reported that when “the snort of the iron horse” was first heard in Williamsburg on Friday, October 14, “it seemed” as if the community “had suddenly awaked from lethargy of 200 years” and that “men, women and children thronged the sidewalks wild with excitement.” The one-paragraph item on page two was signed by “Veronicus,” who praised the railway’s “superhuman exertion” to complete the work in time for the centennial.

The correspondent for The State, whose pen name was—appropriately enough—“Centennial,” wrote, “The entire town was maddened with delight and filled with joy unspeakable.” And he said, in his summary paragraph, “The completion of the Chesapeake & Ohio to deep water is now a superlative fact constituting a desideratum long desired and wished for.”

The Peninsula Extension of Collis P. Huntington’s C&O Railway connected Richmond, and points westward extending to Cincinnati, with Newport News and the coal piers on the James River that Huntington was building, and the shipyard that he would soon install. When C&O auditors totaled the cost of the extension, it was $2,161,695, “not including equipment.”

Edward H. Lively, a printer by trade and Williamsburg’s postmaster by political appointment, watched with reverence as J. J. Gordon’s hammer drove home the last spike in the extension, and later that day he issued a commemorative broadside. “The rails from both directions came together,” he said, “and kissed, and I thought to myself that the morning and evening stars sang a happy euphony to honor the occasion.”

The spot was Magazine Hill, an undistinguished landmark related to some forgotten Revolutionary War episode when the ruthless British cavalry raider Banastre Tarleton passed that way.

Lively, whose fondness for fancy words suggests he may have been “Veronicus” and “Centennial,” praised the men who “worked dexterously and untiringly to consummate this result that there might be no drawback on the Centennial at Yorktown, the completion of this work being one of the grand auxiliaries to the successful celebration.”

Huntington had promised that his trains would take participants and spectators from Richmond directly to the Yorktown festivities on a temporary spur line from Lee Hall, nine miles below Williamsburg in Warwick County, northward to the Moore House on the bank of the York River where in 1781 the articles of Cornwallis’s capitulation were signed. Construction of this five-mile branch began October 5 and followed winding wagon roadways, yet was halted a mile short, ending at an American siege line.

The rails were still being put down as locomotives slowly advanced, carrying militia regiments from Kentucky, Massachusetts, and Virginia—and, boarding in Williamsburg, a hometown contingent, the Wise Light Infantry Blues, outfitted in new uniforms. The inaugural trip, on the night of October 18, took fourteen hours, “the track being finished just ahead of us,” T. B. Benactrin remembered three decades later.

The next day a locomotive with a couple of coaches departed Newport News for Yorktown, arriving at 1 p.m., “too late,” recalled George Benjamin West twenty years afterward, “for the grand parade that day.” His return trip started at dusk, and West wrote, “That night, bushes [were] striking against the car window. I think there was an excursion from Richmond by the C&O the same day.”

Within a week the Yorktown spur was removed, as Huntington intended.

For the C&O’s managers, building the seventy-four-mile Peninsula Extension was a feat fraught with frustration. The route—“through battlefields and over the path of pioneers,” the Dispatch said—had been surveyed and staked westward from Newport News in December 1880 and eastward from Richmond in February 1881. The rails were to join by June, or July at the latest. Trains had to be running by October, as advertised.

The route designated would pass just north of Williamsburg, but clip the northeast corner of the city’ corporate limits at the spot where Capitol Landing Road from Queens Creek in York County becomes, in the city, Waller Street. A crossing would be necessary, but a sunken one because the path for the railroad would have to be dug through an elevation of the ground.

The station to serve Williamsburg passengers and the water tank to refresh boilers of the steam locomotives would be nearer the city’s downtown, at the end of North England Street, about three short blocks north from Nicholson Street and the public green behind the Courthouse.

The C&O’s chief project engineer, J. S. Morrison, thought that “it is very desirable on the part of the city to have a depot at a point more convenient to the businesses . . . than will be practicable on the line as now located.” That meant, he said, that either Scotland Street or Prince George Street would have to be vacated. In correspondence with the city council, he implied the suggestion was instigated by “some of your citizens” and would be considered only if “not . . . against the interest of the company.”

February 25, the council granted the C&O permission to use “the entire width and length of Scotland Street,” but judging by the 6-5 vote, the issue closely divided townspeople. From North Boundary Street on the west, Scotland Street ran eastward across Palace Green in front of the Matty School and stopped. To bring the Scotland Street rails further eastward would require the acquisition of three parcels of private land. The C&O already had condemnation authority to take property owned by W. W. Vest, a leading merchant, and Dr. Robert M. Garrett, a retired physician and a councilman who opposed the Scotland Street plan.

Needed was passage through a tract owned by Charles W. Coleman that had not been condemned for use by the railroad. Dr. Coleman was the community’s beloved physician and was married to the history-minded Cynthia Beverley Tucker Coleman; the couple surely did not want trains in the backyard of their Nicholson Street home—the house in which, in less than eight years, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities—now Preservation Virginia—would be founded.

The council appointed three of its members to keep in contact with Morrison: two lawyers and Postmaster Lively. Within a week the council convened again, and all eight members present “invited” the C&O “to condemn the portion of land owned by Dr. Coleman and that it be paid for out of the funds from the city.”

The railroad’s coming aroused keen public interest in advance of the annual municipal election May 26; voter turnout—though limited to white males—was three times greater than the previous year. Nine incumbents who sought reelection were returned. The vacancies in the twelve-member council were filled by a farmer, who may, according to the 1880 Census, have lived in James City County; Benjamin B. Wolfe, who resided on Scotland Street; and Dr. Charles W. Coleman.

The mayor, John A. Henley, a 62-year-old storekeeper, was unopposed and elected separately with 177 votes; he presided at council meetings and served as municipal judge. Council committees administered city affairs—finance, support for the poor, streets, markets, and lights—and the city sergeant enforced ordinances. Coleman, Wolfe, and Lively were assigned to the street committee.

When the outgoing council convened June 8 at the end of the fiscal year, roll call was taken, and the meeting immediately adjourned. The minutes are mysteriously silent. It can be assumed that the invitation to condemn Coleman’s backyard was rescinded, or rejected by the C&O. To proceed with the Scotland Street route would have been costly and taken far too much time, and was against the railroad’s interest.

Morrison was in a hurry—a hurry to catch up. On a good day, a crew could lay a mile of track over a woodland route cleared of trees and excavated through hills and with ravines filled and brought up to grade. There were trestles to be built across White Oak Swamp and Diascund Creek, the border between James City and New Kent Counties. At work were crews of hundreds of African Americans and German immigrants. Some had built Huntington’s rail lines in the far West, as had J. J. Gordon.

As the Peninsula lines converged, ploddingly and behind schedule, a decision on whether to take the designated route around or a temporary route through Williamsburg remained. In June, the completion date was pushed to mid-September. In July, the Washington Post reported, and the Richmond Dispatch repeated: “It is stated as a fact that the people of Williamsburg were opposed to any railroad passing through their town because they did not want any of their streets cut up.”

The city council minutes don't say who opposed. When the new council convened July 1 to reorganize committees, to appoint a trustee for free public schools, and to pay bills, the C&O must have been discussed, but no summary was recorded. If the C&O had to come through Williamsburg, there was only one possible way—Main Street, as the Duke of Gloucester was known at the time—and to use it, council had to grant permission.

Tracks on Main Street would restrict intersections and pedestrian crossings, and locomotives would frighten horses. The lives of families who lived on Main Street—including those of eight councilmen—would be interrupted.

A New York Times reporter in Yorktown before the centennial wrote that it had been rumored the “Williamsburg turnpike was to be used as a temporary short cut, but at the last minute Williamsburg refused to allow the line to be run in this fashion, and got an injunction against the railway.” If the council did, no court record survives.

Morrison and Gordon were under pressure to complete the Peninsula Extension. Ticket agents in Richmond were booking rail passage to Yorktown for militia units with weapons and tents.

Since the Peninsula Extension of the C&O—even if completed as intended—could never accommodate the thousands expected at Yorktown, arrangements were made to add locomotives to the York River line of the Richmond and Danville Railroad, which terminated at the summer resort town West Point, where the Mattaponi and Pamunkey Rivers converge to form the York. From there, passengers would board steamboats for Yorktown. The rail-and-water trip would take four hours one way, and a round-trip ticket cost $2.25. Five trains would leave Richmond during the morning and return in the evening. Four steamers with a combined passenger capacity of 5,700 would ply between West Point and Yorktown. Travel arrangements via West Point were advertised in Richmond newspapers; no schedule for the Peninsula Extension was published.

In an era when railroads were big news, The State newspaper published a weekly column headed “Locomotive Sparks.” September 12 it said, “Track laying on the Newport News road is progressing at the rate of a mile a day. Forty miles have already been laid.” Unreported, but surely weighing heavily on the minds of Morrison and Gordon, was that thirty-four miles of track had to be put down in five weeks.

The next day, Williamsburg’s city council convened, and it became apparent that a deal had been made: the C&O could use Main Street for three months and was given a permanent right-of-way at the Waller Street–Capitol Landing Road crossing. In return, the C&O would erect a bridge for the wagon road over the rail line. The bridge was to be thirty feet wide and, because its slope was steep, equipped with a pedestrian handrail. When the temporary track was pulled up, Main Street was to be “left in as good condition as when found.” No individual vote by council members was recorded, the minute book saying only that the agreement was “ordered,” presumably by unanimous consent.

Just who negotiated this agreement is unknown, but it is obvious Morrison and Gordon realized they could not meet their construction timetable unless they could direct the tracks down the middle of Main Street—and that gave city officials a strong bargaining position. The bridge would be the only one over the Peninsula Extension; all other crossings were at grade.

But the matter wasn’t settled. Ten days later the construction engineers wanted permission to run a parallel rail siding “on the south side of Main Street beginning at or in front of the Courthouse and thus extending 600 feet each way.” The council acquiesced, and requested the C&O “put in passable condition the back street on the south side of town,” that is to say, Francis Street, giving the city a second east-west through road.

As Main Street was being paved with steel bands, the council posted notice that no horse or cattle were to “be allowed to be tied to the trees on the streets,” and that City Sergeant Parke Slater was to assess a $1 penalty for each infraction.

“I as present when this track was laid,” said James P. Nelson, a C&O supervising engineer. Another Virginia railroad, however, was then the focus of attention. At Howardsville, along the James River canal path west of Richmond, a rail line to Lynchburg was ceremoniously opened, an account of which filled the front page of the Richmond Dispatch on Saturday, October 15—the day before the Peninsula line was joined at Magazine Hill.

After the centennial celebration ended, construction trains ran over the Peninsula Extension “during the seasoning period of the roadway," Nelson wrote. "Light local traffic was handled” along with locomotives hauling boxcars and flatcars loaded with building materials for the wharves at Newport News. While trains passed through Williamsburg, laborers with shovels were grading the bypass around Williamsburg and gandy dancers followed laying track.

George Benjamin West rode home to Newport News in a night train after attending the Virginia State Fair in Richmond in early November:

We left Richmond at 9 P.M. with a dozen or more, most from Williamsburg, & when they got off I was the only passenger . . . after leaving Williamsburg got so soundly asleep that I did not awake till the conductor informed me we were at N.N. This was after 4 a.m. The C&O road that night ran down the Main Street of Williamsburg.

Alongside the southern side of the railroad’s permanent roadway, C&O carpenters erected a small train station for Williamsburg with a passenger platform and a freight-car siding. The city council arranged for a short access street to the station, named for Benjamin S. Ewell, president of the College of William and Mary, who donated a right-of-way. To the east of the station, and within sight, a humpback wagon bridge to Capitol Landing Road was built. Here, however, the C&O didn’t fully meet its obligation, since the bridge, when finished, was only twenty feet wide.

Because all work went slowly, perhaps hampered by the onset of winter, the C&O sought an extension of its deadline to abandon its temporary tracks on Main Street. On December 12, the council granted the railroad “until the first day of February 1882 or by such time by due diligence they complete their road on the main line outside the city limits.”

When the tracks were taken up is not known, but in early March, Mayor Henley said that Main Street was “almost impassable.” The council shot off a letter to the railway’s general manager in Richmond, C. W. Smith, demanding “our Main Street” be “put in proper condition.”

Postmaster Lively, who was so appreciative of the energy displayed by the C&O’s construction crews, was charged with seeing that Smith got the message. Apparently, he did, and responded accordingly.

At the advent of spring weather, the C&O put a notice in the Richmond papers announcing that “on and after Monday, May 1, 1882, trains will run daily (except Sunday)” to Williamsburg.

Regular rail service began without fanfare or ceremony, no locomotive festooned with bunting; no speeches, no vociferous cheers to ring through the sky, no presentation of first tickets to the conductor, “Captain Berkeley”—for surely, otherwise, a photograph would have been taken.

Journalist Will Molineux contributed “The Visit of the Yeggmen” to the summer 2007 journal, and writes the “We are favoured” section in each issue.

Suggestions for further reading:

- David Levender, The Great Persuader: A Major Biography of the Greatest of All the Railroad Moguls, Collis P. Huntington (New York, 1969).

- James P. Nelson, “Memorandum Concerning Extension of the Railroad of the Chesapeake and Ohio Company from Richmond to Newport News and Old Point, Va.,” (typescript, 1936).

- New York Times, 1881.

- Richmond Daily Dispatch, 1881, 1882.

- The State (Richmond, VA), 1881.

- William R. Vivian, “The C&O Extension, 1881 to 1981,” Chesapeake and Ohio Historical Newsletter, XIII, no. 10 (October 1981).

- Washington Post, 1881.

- George Benjamin West, handwritten, untitled autobiographical journal, ca. 1903, published as When the Yankees Came: Civil War and Reconstruction on the Virginia Peninsula, ed. Parke S. Rouse Jr. (Richmond, VA, 1977).

- United States Census for Williamsburg, VA, for 1880.

- Williamsburg City Council minutes of 1881, 1882, 1891, and 1892.