Online Extras

Zoom in on Political Prints

Massachusetts Historical Society

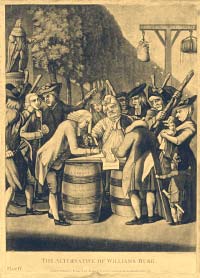

Williamsburg’s Liberty Men gave loyalists a choice of signing allegiance to their cause or visiting the Liberty Tree’s tar and feathers.

Colonial Williamsburg

Williamsburg’s Liberty Men gave loyalists a choice of signing allegiance to their cause or visiting the Liberty Tree’s tar and feathers.

Library of Congress

Paul Revere dedicated to sons of liberty an engraving of the Boston Common obelisk celebrating the Stamp Act’s repeal.

Library of Congress

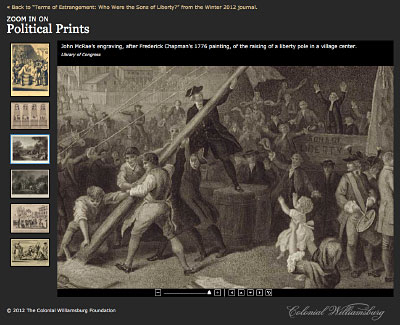

John McRae’s engraving, after Frederick Chapman’s 1776 painting, of the raising of a liberty pole in a village center.

Terms of Estrangement: Who Were the Sons of Liberty?

by Benjamin L. Carp

A group of nine Boston craftsmen and shopkeepers gathered the evening of December 16, 1765, at Chase & Speakman’s distillery to write a letter to Andrew Oliver, the stamp officer appointed for Massachusetts. It demanded he appear at noon the next day at the Liberty Tree to publicly resign his office. “Provided you comply with the above,” the letter said, “you shall be treated with the greatest Politeness and Humanity. If not. . . .”

The next morning Bostonians who braved the day’s stormy weather found notices posted all over town, calling for the “True-born Sons of Liberty” to meet Oliver at the Liberty Tree. Oliver resigned his office in front of two thousand rain-soaked townspeople. There was now no one to enforce the Stamp Act in Massachusetts. At the time, Boston had fifteen or sixteen thousand inhabitants, and most were women and children, so the turnout was significant.

The Stamp Act, passed by the British Parliament in early 1765, levied a tax on colonial legal documents, licenses, port clearances, newspapers, cards, and dice. As soon as they heard about the law, American colonists began complaining that this was a new form of taxation without their consent.

Ever since this debate, Americans have held certain constitutional principles sacred, and they have often resorted to public protest when they believe the government is behaving unjustly. Sometimes such protests have been spontaneous and disorganized, but very often there is leadership, organization, and broad commitment underpinning an act of popular mobilization.

In Boston in 1765, the organizers who coordinated the public resignation of Andrew Oliver were initially known as the Loyal Nine and later as the Sons of Liberty—which almost certainly included more men than these ringleaders. The Loyal Nine had achieved a rousing success at the Liberty Tree, which they toasted that night. But what did it mean to be one of the true-born Sons of Liberty in America?

The term “sons of liberty” or “sons of freedom” was a generic term of national pride in the eighteenth century, usable on both sides of the Atlantic for anyone who felt that English, and later British, liberty was his birthright. An English writer in 1753 knew that his readers, as “sons of liberty,” would recoil at tales of despotism in India and elsewhere. An Irish Protestant might rally his compatriots with the phrase. Essentially, a British son of liberty was the same thing as a patriot, or a “friend of his country.” In the 1760s, when Americans took pride in their identity as British subjects, they thought of empire and liberty as one and the same.

But in 1765, the relationship between Great Britain and the colonies changed, and so did the meaning behind the phrase “Sons of Liberty.“ The phrase caught fire in America when Colonel Isaac Barré spoke against the Stamp Bill introduced in Parliament in February 1765. Barré was a veteran of the French and Indian War. On the Plains of Abraham in September 1759, he had taken a bullet in the cheek and lost the use of an eye. He believed colonial Americans had ably confronted their hardships while cherishing “Principles of true english Lyberty.” Yet now, in the 1760s, British officials were misrepresenting the colonists and preying upon them: their behavior, he said, “has caused the Blood of those Sons of Liberty to recoil within them.”

American colonists thrilled to Barré’s words, and they named towns after him in Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Vermont. Perhaps they would have continued to use the term in its generic sense whenever they were marking out friends and enemies to America—but Barré had given the term “Sons of Liberty” new power.

Nearly everyone in the colonies hated the Stamp Act, but the Sons of Liberty came to refer to a specific group of American men organizing against British policies. In September 1765, the acting governor of New York worried about a “secret Correspondence” between the colonies. Sometime in that autumn, a group of New York City agitators began meeting in secret, having evidently resolved to prevent the Stamp Act’s execution.

Cadwallader Colden, acting governor at the time, wrote in August 1765 that “The People of New York are surprisingly excited to sedition by a few Men, but I hope their wicked designs will be defeated and their machinations end in their obtaining the reward they deserve.” In Philadelphia, printer William Bradford wrote in February 1766, “Our body of Sons of Liberty in this city is not declared numerous as unfortunate dissensions in provincial politics keep us a rather divided people.”

In spite of Colden’s hopes and Bradford’s dismay, the Sons of Liberty increased the numbers in their ranks. In December 1765, a delegation of Sons of Liberty from New York City traveled to Connecticut towns to urge joint resistance to the Stamp Act—even if it meant taking up arms. By early 1766, the term “Sons of Liberty” was commonly used in colonies up and down the seaboard, from New Hampshire to Georgia, as towns agreed to correspond, and perhaps to join a military alliance. By now, the term had crystallized to mean an organized group acting to protest against the Stamp Act’s implementation.

The Sons of Liberty did their utmost to spread word of their actions throughout the colonies, and to Great Britain. They published pamphlets and newspaper articles, which were circulated and sometimes read aloud in taverns. They also established direct links to one another. On March 31, 1766, hundreds of Norfolk, Virginia, inhabitants gathered to hear a leading group of Sons of Liberty read a series of resolutions. The last appointed a committee to “correspond, as they shall see occasion, with the associated Sons and Friends of Liberty in the other British colonies in America.”

The organization succeeded—Americans nullified the act by forcing stamp officers to resign and closing ports and courts, or allowing them to proceed without stamped paper. Historians have characterized the Stamp Act crisis as Americans’ first step toward revolution. Parliament repealed the Stamp Act before the crisis could explode, but the Sons of Liberty—or Liberty Boys—in several colonies now had the benefit of training in organization, communication, and the occasional reliance on force.

What sort of person belonged to the Sons of Liberty? For the most part, the chief organizers were lawyers, merchants, gentlemen, and prominent master craftsmen—many were involved in the colonial legislatures.

As riots broke out in such cities as Boston, Newport, and New York, they became concerned about preserving order. Occasionally, colonial leaders, including those who later supported American independence, suppressed seamen, tenant farmers, disenfranchised backcountry farmers, and the enslaved who took the cry of liberty too far. At the same time, colonial leaders felt compelled to reach out to neighbors from all walks of life. They forged alliances with shoemakers, sailors, carpenters, and tailors. The parades, crowd activities, and street theater of American resistance mobilized people against hateful laws from overseas.

Sons of Liberty gathered on anniversaries of the Stamp Act’s repeal—March 18, 1766—to celebrate their achievement. They wrote songs and erected liberty poles in the squares of their towns. Occasionally they corresponded with their counterparts in other cities or, from 1768 to 1770, associated against the importation of British goods. Sometimes the Sons wrote to offer words of encouragement, sometimes to scold their counterparts for lapses. Organized groups in American towns and cities broke apart and reconvened as caucuses, clubs, committees, lodges, or meetings of the “Body of the People.”

Sometimes these groups took the name of Sons of Liberty or Liberty Boys, and sometimes they didn’t. Being a child of liberty was a flexible concept, and sometimes controversial. Although women couldn’t vote or hold office in the American colonies, quite a few writers called on women to join liberty’s cause.

March 4, 1766, in Providence, Rhode Island, eighteen “Daughters of Liberty, young Ladies of good Reputation,” assembled at the home of Dr. Ephraim Bowen to spin cloth, eat dinner—with no tea—and declare the Stamp Act unconstitutional. May 1, in the courthouse of Norwich, Connecticut, 101 “Daughters of LIBERTY” gathered for another spinning match. There were other such meetings. Through hard work and frugality, and by abstaining from tea and other imported luxuries, men and women could demonstrate that they cared about constitutional rights.

In late 1768, the Daughters of Liberty responded to a new revenue act: the so-called Townshend Duties on paper, lead, painters’ colors, glass, and tea shipped to America. Women announced new resolutions to drink no tea. “Let the Daughters of Liberty nobly arise,” read a poem. In 1770, 137 New York City Daughters of Liberty visited the imprisoned patriotic merchant Alexander McDougall, who writing as “A Son of Liberty,” had penned a broadside accusing America’s enemies of trying “to enslave a free people.” Then they waited on his wife. Women, like men, could show that they felt responsibility for one another.

So what, then, can we call those Americans who were protesting against Parliament’s policies before 1775? We can’t call them simply “Americans” or “colonists,” since opinions among colonial Americans varied. They sometimes referred to themselves as Whigs, but this is a tricky term for history readers who might confuse them with the Whig party of Great Britain, or the nineteenth-century Whig party of the United States. To call them rebels in 1765 is premature, and radicals seems needlessly pejorative. The Sons of Liberty singled out “friends of government,” many of whom later became Loyalists, as “enemies to their country,” but the supporters of imperial government were equally convinced that the Sons of Liberty were a threat to British stability and liberty.

These “friends of government” could be quite sarcastic with terms like “patriot” or “Sons of Liberty” when referring to the protestors. They sometimes referred to them as the “Sons of Faction” or the “Sons of Violence.”

“Dare to withstand those Devils,” wrote William Paine of Worcester, Massachusetts, in November 1773, “that call themselves Sons of Liberty. But from such Liberty! good God! deliver us.” Paine was writing to Isaac Winslow Clarke, Andrew Oliver’s nephew and one of the Boston merchants appointed to receive the East India Company’s tea, urging him to stand firm and resist the pressure of the Boston crowd. Andrew Oliver’s brother, Peter, later wrote caustically about “these Christian Liberty Men” who thought “they did God good Service in persecuting & destroying all those who dared to be of different Opinions from them.”

Similarly, a Boston newspaper writer ridiculed the “fair Daughters of Liberty” for participating in politics. Although some of Boston’s women had deemed tea-drinking treasonous, the chauvinistic author doubted that women would refrain from drinking it. Instead, his satire portrayed women as “determined, constantly to assemble at each others Houses, to HANG the Tea-Kettle, DRAW the Tea, and QUARTER the Toast.”

Colonists also worried that African Americans were picking up on the refrains of liberty. During the soldiers’ occupation of Boston in 1768, newspapers printed the following rumor: a British captain and two other officers “endeavoured to persuade some Negro Servants to ill-treat and abuse their Masters, assuring them that the Soldiers were come to procure their Freedoms, and that with their Help and Assistance they should be able to drive all the Liberty Boys to the Devil.”

Perhaps this was the product of a feverish American imagination: the idea that British troops would point out the hypocrisy of white Americans’ styling themselves Liberty Boys while keeping black men and women in bondage.

Yet this critique became more widespread among Britons and Loyalists once Americans moved beyond protest to outright rebellion. July 4, 1776, the Continental Congress approved the Declaration of Independence, hoping to secure the rights to “Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” A week later, Ambrose Serle arrived in America to serve as secretary to the British Admiral Richard Howe, one of the commanders of the war effort against the rebellious colonies. Serle wrote that in North America, “there is nothing to be heard but the Sound of Liberty, and nothing to be felt but the most detestable Slavery.”

It was left to later generations of Americans to abolish “detestable Slavery” in America. In 1859, a longtime congressman named Joshua Giddings became frustrated with the unjust nature of American laws upholding slavery. He established a committee in Ashtabula County, Ohio, to use force against slave catchers.

What did he call his committee?

The Sons of Liberty.

Benjamin L. Carp, associate professor at Tufts University in Medford, Massachusetts, teaches colonial, revolutionary, and early American history. His latest book is Defiance of the Patriots: The Boston Tea Party and the Making of America (Yale University Press, 2010). His two-part WGBH Forum Network podcast, “Tempest in a Teapot: The Boston Tea Party of 1773,” is available at iTunes U. This is his first contribution to the journal.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Benjamin L. Carp, Rebels Rising: Cities and the American Revolution (New York: Oxford University Press, 2007).

- Pauline Maier, From Resistance to Revolution: Colonial Radicals and the Development of American Opposition to Britain, 1765-1776 (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1972).

- Edmund S. Morgan and Helen M. Morgan, The Stamp Act Crisis: Prologue to Revolution (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1995).