To Live Like a Slave

by Curtia James

photography by Dave Doody

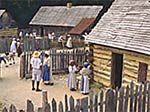

Shouldering tools, reenactment slaves trek to the fields under a merciless sun.

I SAT BEFORE a crackling fire, dressed in 18th-century clothes, and listened to the haunting sounds of spirituals. I watched shadows flicker across the faces of my African-American co-workers, gathered to re-enact the lives of the 24 blacks who had inhabited the Slave Quarter at Carter's Grove in 1770. We would give voice to their experience, rediscovering aspects of their day-to-day realities as much as our 20th-century sensibilities could allow.

I had often wondered about those slaves. But sitting here in spaces they once called home, I thought especially about what they would think about us being there. If they could have seen ahead to our times, would they think it foolish for us to want, rather desperately, to dress as they would have done, to walk in their erased paths sifting for glimmers of their long-gone days and times? I contemplated what they might think of what we as a free black people had accomplished. We were there because someone like them had the will to survive. Would they, surveying us, celebrate our personal successes and sympathize that racism, which held their lives so imperiled, could today still be so profoundly felt?

They are but characters--remembered daily in the interpretation at the quarter--theoretical people researchers summon from 200-year-old plantation records from the slaves' owner, Nathaniel Burwell, and Bruton Parish Church registers. Because evidence about them is so scant, any attempt to fully re-create their lives would be mere conjecture. What was more realistic, we felt, was to approach the re-creation as slave descendants.

I recall hearing about these slaves a year ago when for the first time I had crossed the foot bridge from the reception center to the Slave Quarter. My major concern was whether the site could broach a subject that I wanted no one to forget, but that I, ironically, felt hesitant to face. Slavery had always been an emotional subject for me, one wrought with the confusion, anger, and pain it poses for many African- Americans. As a communications associate assigned to cover the Foundation’s department of African-American interpretation and presentations, my responsibility is to familiarize people with the issue of slavery, to make them understand the institution as a fact of American history.

As an observer at the quarter, I was more than a reserved professional. I was face to face with the living conditions of my ancestors. The sight was chilling. I glanced around at the all-white crowd around me, curious about their perceptions of slavery and the buildings before us. Interpreter Sylvia Tabb-Lee put us at ease.

"Good morning," she began. "Welcome to Carter's Grove and to the Slave Quarter. In the 1970s, this property was excavated and root cellars were discovered with personal belongings in them. Postholes were discovered, so we know this is the original location where the slaves would have lived."

She said that two percent of the population lived as well as the people in the mansion. "If you happen to be two percent of the population then you can look back and say what a romantic period. But if you happen to be everybody else, welcome home. Because the average person lived in a 15-by-15-foot house with a dirt floor just like these."

Completed in 1989, the Slave Quarter consists of four largely wooden structures: a two-family

dwelling, a larger dirt-floor house with space for a family on one side and single males on the

other, the foreman's dwelling, and a corn crib. The structures surround a communal courtyard area

and are reminiscent of places where slaves lived in the colonial Chesapeake area, most of which

survived only a generation or two.

Completed in 1989, the Slave Quarter consists of four largely wooden structures: a two-family

dwelling, a larger dirt-floor house with space for a family on one side and single males on the

other, the foreman's dwelling, and a corn crib. The structures surround a communal courtyard area

and are reminiscent of places where slaves lived in the colonial Chesapeake area, most of which

survived only a generation or two.

When Sylvia finished her 10-minute presentation, I introduced myself to her and the other interpreters and walked along the oyster shell encrusted pathway to look inside the first cabin. A rustic building, it served hypothetically as Venus's space, shared with her daughter Sukey, granddaughter Nancy, and great-grandson Lewis. Their belongings consisted of a few eating utensils and a straw-filled burlap mattress on the floor.

I walked across the courtyard and gazed into the two-sided larger house with its fireplace, raised bed, and scattered furnishings where the carpenter Joe lived with his wife Nanny and small children. A group of field hands, including Manuel and Bristol, lived next door. Seventy-year-old Paris had his own space, a lean-to built on the front and right of the structure.

In the early 1970s, Foundation archaeology revealed circular postholes that suggested a West African kraal, a round fenced enclosure re-created beside both two-family dwellings and the corn crib. Adjacent to the crib is a foreman's cabin furnished with, among other things, a violin--reflecting slave ads that described runaways as skilled violinists--and a Virginia Gazette, illustrating that some slaves could read.

A year following my introduction to the Slave Quarter, I found myself back there dressed in costume in 100-degree weather, crowded around Sylvia and other interpreters. I stood patiently as character interpreter Arthur Johnson taught me to fasten the intricate buckle on my shoe, and I braced myself for the evening ahead. For juvenile performer Holly Smith, it was an opportunity to gain a first-hand appreciation of slave life. "They weren't just going to Saturday night gatherings," she said. "They were working hard."

Three months of planning had gone into that afternoon and the following night and morning at the Slave Quarter. Minute-by-minute schedules called for interpreters to arrive in stages to take part in specific activities or appear in scenes ranging from a runaway segment to sisters determining a cure for an ailment.

Nervous conversations tittered about us as we rose to take part in the first scene. I asked former interpreter Jerrold Roy, a Hampton University history professor, what had lured him back to the quarter. "I opened this place in 1989," he said. "We have been talking since this place opened about spending the night here."

We walked into the courtyard where others were gathering wood to make a fire. The sight of so many interpreters in costume was daunting, a convincing tableau of how the slaves may have looked and interacted.

Some, like me, were in costume for the first time. As I dressed for the re-enactment, I resisted the instinctive urge to apply my lipstick and felt apprehensive as I removed my watch. My modern-day sensibilities were quickly humbled when I climbed out of my car into the hazy afternoon heat, leaving my air conditioning behind. Without a watch, I felt an uncanny feeling of timelessness.

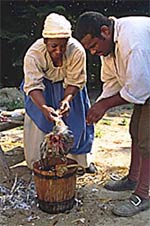

BEFORE LONG the activities began, which ranged from folks milling about the garden, communing,

cooking-and me pounding corn into meal. The women crowded around to watch as fish were scaled for

our dinner. Others gathered to hear Roy, depicting a Baptist minister, point out the paradox of

slavery from a religious perspective. "They says we supposed to be slaves, that the good book

says so," he preached." But you know, I see right here in the book of Matthew 6 and verse

24 that no one can serve two masters. Or he's liable to love one and hate the other."

BEFORE LONG the activities began, which ranged from folks milling about the garden, communing,

cooking-and me pounding corn into meal. The women crowded around to watch as fish were scaled for

our dinner. Others gathered to hear Roy, depicting a Baptist minister, point out the paradox of

slavery from a religious perspective. "They says we supposed to be slaves, that the good book

says so," he preached." But you know, I see right here in the book of Matthew 6 and verse

24 that no one can serve two masters. Or he's liable to love one and hate the other."

Some in the crowd, hanging on his every word, dissolved into a medley of amens, while some moved on to spend time chatting.

Later, in a secluded section of the larger two-family house, interpreter Larry Earl teamed up with Roy to depict the slaves Manuel and Bristol arguing over one's desire to run away that evening and the other's desire to stay.

"So, you tell me, what I got to stay here for?" Earl bellowed. "To pick his

tobacco?"

"So, you tell me, what I got to stay here for?" Earl bellowed. "To pick his

tobacco?"

"So where you going to go?" Roy asked.

"To Norfolk."

"You can go over to Norfolk if you want. You still going to be a slave."

Next door Joe the carpenter was teaching his son Tarik to use a wood shaver.

The laughter and excitement of the children, which followed us throughout the quarter, was enchanting. As they assembled for their roles, played with one another, or chased the chickens, they exuded a refreshing spirit of freedom.

Earlier in the day I had watched one of our costumed children stare as a visitor's son wearing a tricornered hat walked by. As each waited for the other to make a move, signaling the proper overture to begin to play, I realized that even 200 years ago, children must have been somewhat oblivious to slavery, much as they are to racism today.

Yet they must have seen those they loved be sold, one interpreter reminded me, "even one another."

"You know they begged the master not to sell one another," a fellow interpreter added.

Later I watched as Emily James, one of several mothers on hand for the evening, bed down the children. She spoke of her own daughter and said she would have resented the master living in his big house while she and her husband Greg, another re-enactor, and child battled mosquitos and disease in the quarter.

Her face softened, however, as she sat thinking after a while. ""Most of all though," she said, "we would have felt fortunate to have the opportunity to spend the year together as a family."

Earlier that evening I had experienced the black music program. As one born somewhat rhythmically deficient, I had always admired the dancers from afar. But with the chance to dance with them within my grasp, I seized the moment. Rosemarie McAphee-Byrd, who was working with the dancers, initially had asked me to play an instrument.

"But I want to dance," I told her quietly."Okay," she said, moving off to her side of the circle. "But dance beside someone who knows what they're doing."

I could barely contain my excitement. As the soloist began "Pan Logo," one of the most popular dances the department performs, I filed in behind Emily, determined to mimic her every step. There was something heady about the sound of the drum, the smell of the fire, and the exuberant smiles on the faces around me that warmed me through and through, lifting my soul, minimizing my self-doubt about the awkwardness of my movements.

The darkness blurred the modern, diffusing such intrusive images as someone drinking out of a

20th-century cup or a mother applying insecticide on her child. Suddenly I understood why the

slaves had danced, sometimes all hours into the night. Beyond sheer entertainment, it was a way to

shed, if just for a moment, the glare of reality, to commune with the earth, the trees, the skies.

The darkness blurred the modern, diffusing such intrusive images as someone drinking out of a

20th-century cup or a mother applying insecticide on her child. Suddenly I understood why the

slaves had danced, sometimes all hours into the night. Beyond sheer entertainment, it was a way to

shed, if just for a moment, the glare of reality, to commune with the earth, the trees, the skies.

I tired out long before the others, but sat contentedly as they moved on to other dances, dissolving into a curious mix of popular tunes and spirituals that lasted long into the night.

My bed was a pile of straw with a blanket thrown over it outside by the fire with five other interpreters. After the stifling heat of the past few days, the breezes that swished through the trees overhead were a welcome respite. I slept soundly.

The insistent crowing of a rooster awakened us the next day to face our most grueling task"depicting slaves in the field. We toted our hoes and rakes and spades behind a horse-driven cart filled with taunting children. Working for less than half an hour in the heat filled us with awe concerning our ancestors' endurance. It drove home to us, like nothing else, how difficult and thankless slavery must have been. They say you can get used to anything. We just couldn't imagine getting used to forced, exhausting work like that.

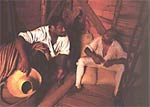

Ywone Edwards and Robert Watson, Jr., pluck feathers from a rooster

Robert C. Watson skins a rabbit.

Interpreter Larry Earl discovered, as I had, just how much slavery was an oppressor of the mind with the body led in tow. "I can tell visitors what it felt like sleeping on boards on a floor," he said, "and I can say it was pretty comfortable. It's not the living condition. It's the work."

Later we shared our thoughts over a breakfast of hominy, fried potatoes and onions, and scrambled eggs that Emily, Rose, and Sylvia had prepared. Afterwards we watched Robert C. Watson skin a rabbit that Robert Watson, Jr., (no relation) had shot earlier that morning. Before we knew it, it was time to depart.

Emily James and Sylvia Tabb-Lee catch up on things as they teach Tiffany Taylor to scale fish.

A rooster runs for its life from Dakari Watson.

It has been a few weeks now since I climbed wearily into my car and back into my modern-day persona. Looking back, I realize I had always only perfunctorily thought of my own ancestors who dwelt on some other quarter in Georgia, withstanding trials I've never known. Perhaps their now silenced struggles are quelled in that tender, fearful place in my psyche, cowering in my heart, that I had always reserved for slavery.

But these days, I do think about them, as though I know them well. Somewhere between pounding the corn one day and hugging my co-workers goodbye the next, their presence became indelibly etched in my being.

I wonder if they somehow endured because they knew one day things would be different. I wonder if they could have possibly sensed how thankful I would be to be their survivor. I really wonder.

Reprinted from the Colonial Williamsburg Journal, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Autumn 1993), pp. 14-24.