Apples, Putlog Holes, and Provost Marshals

A Christmas Tradition Added to Palmer House History

by Jim Bradley

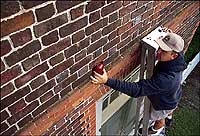

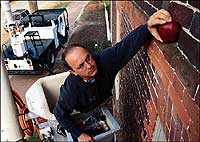

Perched in the bucket of a cherry-picker crane, arborist Rick Stanley stretches to wedge an apple in a Palmer House putlog hole. A Christmas tradition, the practice began in 1953, soon after the 18th-century home was restored.

The tall brick home at 430 West Duke of Gloucester Street has been called the Kerr House, the Vest Mansion, and the Palmer House in its nearly 250 years, but it may be known best today as the house with the Christmas apples.

Try Christmas the regularly spaced niches in the Flemish-bond brick façade wink with shiny red apples. So adorned, the Palmer House—its official Colonial Williamsburg Historic Area name today—becomes a must-see for December visitors. Who puts those apples way up there, and how, and why?

It takes a hydraulically-operated mobile crane—a "cherry-picker"—to carry the crimson fruit up into the brickwork. A long, folding arm, with an oversized bucket at the end, hoists a landscape department employee into the late autumn air. Two stories above the street, bucket and rider visit each niche. The ritual repeats through the month—as often as required by the weather and the appetites of Williamsburg's birds. In winter, birds make quick work of ripe apples.

The niches are concessions to the 18th-century realities of building two-story masonry walls. Called putlog holes, they supported the scaffolding as masons laid course upon course of brick. Often, putlog holes were filled with mortar when construction was complete. The putlog holes of the Palmer House stayed open for two decades, until 1779 when mortar filled the blanks, but it wasn't until 1953 that they were filled with apples.

Harold Sparks, retired Colonial Williamsburg vice president of marketing and merchandising, moved into the Palmer House in 1952, soon after it was restored and the putlog holes were reopened. In an interview just before his death on August 28, Sparks said that he began the apple tradition.

Sparks launched his holiday decorating by hanging a Yule log, strung with long-leaf pine boughs and fruit, next to the front door. Colonial Williamsburg's architect's office, responsible for the integrity of Historic Area buildings, reprimanded Sparks for drilling a hole in the brick to insert a hook to support the log.

The next year, Sparks decorated the Palmer House's front-step iron railings and, borrowing a ladder from the architecture, construction and maintenance department, he put apples in the putlog holes. The ladder wasn't tall enough to reach the highest holes of the second story—something to remember—but it was a start.

He also discovered that apples left exposed to the elements rot. So, he laquered them, along with the grapes and other fruit he used for decorations, with shellac. A shellacked grape garland was the undoing of a neighborhood rooster. The family across the street kept chickens, including a cock that answered to the name, "Mister Armistead." One holiday season, Mister Armistead braved the stroll across Duke of Gloucester in search of a snack—and spotted the decorative grapes. Mister Armistead must have been hungry and of one mind, because he overlooked Sparks's dog, a dalmatian named Duke. Duke had his eye on a snack, too—Mister Armistead. Sparks said his friend Ann Robb "captured on canvas the scene in the street: Duke and Mister Armistead, in a battle to the death—all brought on by my shellacked grapes."

Mildred Layne moved into the house about ten years after Sparks had gone, and no one told her beforehand about the apples. She had been with Colonial Williamsburg since 1937, when she accepted a position as an architecture department secretary. But the architecture department was in New York. Twenty-nine years later, Layne was still in New York, but as administrative assistant to President Carlisle Humelsine, and office supervisor.

She came to Virginia late in 1966 as Colonial Williamsburg's first female administrative officer, the vice president and executive assistant to the president, and moved into the Palmer House on December 23.

Waiting for her family's belongings to arrive from New York, Layne camped out in the big old place, but, in the spirit of the season, made an effort to decorate the exterior. Early in the morning on Christmas Eve—her second day—a visitor knocked on the door.

"Where are the apples?" the visitor said. "We have been coming here for years, and we have enjoyed seeing the apples every year. This year, we are keeping a promise, and we have brought our grandchildren here to see the apples."

Mystified, Layne gleaned from the caller what she could about the apples. She stepped outside while the visitor pointed to the putlog holes and described the appearances of Christmases past.

"I'll get the apples," Layne said to herself, "but how do I get them in the holes?" She dispatched her brother to the market, and Colonial Williamsburg sent a crane around. No sooner had the apples been mounted, but the birds began their Christmas feast, eating them in place or knocking them to the ground. "At some point, the maintenance department inserted short pegs in the holes to secure the apples in place," Layne says, "but the birds continued to feast on them."

The story of the Palmer House apples is but a chapter in the 290-year chronicle of the property. William Robertson purchased colonial Lots 26 and 27 in January 1708 from the trustees of the City of Williamsburg for "30 shillings of good and lawful money of England" and agreed to erect a dwelling within two years, complying with a 1705 Act of Assembly. He sold the house and lot in 1718 to Dr. John Brown.

sketch made of the Palmer House during the War between the States (left) shows stucco had been applied to the brickwork. The house served as the Union provost marshal's headquarters during Williamsburg's occupation.

Brown died in 1726 but it was nearly six years before his executors sold the property. Jeweler and silversmith Alexander Kerr, a distant relative of colonial Governor Alexander Spotswood, bought a "well-finished brick house, in good repair, together with a convenience store, coach house, stables, and other office-houses, fronting the main street, next to the Capitol."

In the 1740s, lawyer John Palmer acquired the place. Once a clerk in the office of the attorney-general of the Virginia colony, Palmer was admitted to the bar in 1740. He was Bruton Parish vestryman and the College of William and Mary's bursar at his death in 1760. In 1754, a fire broke out in a storehouse, rented to a merchant, and burned several buildings, including the residence. Palmer built the house that stands today, using some of the brick recovered from the ashes.

The property remained in Palmer's estate for 20 years, with such tenants as cabinetmaker Benjamin Bucktrout and Dr. John Minson Galt.

It changed hands through joint ownership between 1780 and 1781, when John Drewidz and Charles Hunt, who lived in the house, operated a snuff manufactory on the property. Drewidz & Hunt were succeeded by Hunt & Adams, snuff manufacturers, and the property stayed in Charles Hunt's hands until 1810. Carter Burwell took title in 1815 and sold it to William W. Vest in 1834.

A prominent merchant, perhaps Williamsburg's wealthiest citizen in the days before the War Between the States, Vest owned and operated a large store on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street. Insurance records show he nearly doubled the size of the house in 1858 with a brick addition at the eastern end and, at the rear, a large porch with a Southern exposure.

Almost a century later, Colonial Williamsburg began returning the house to its 18th-century appearance. That necessitated removal of Vest's eastern addition. Sparks said the community was convinced that the architects and historians were making a mistake. Surely, the large center hall structure was an original. When the demolition began, however, it exposed the original brick exterior with ivy vines intact that 19th-century carpenters, masons and plasterers had covered.

The threat of war in 1862 must have concerned Vest. When the Union Army took Yorktown during the Peninsula Campaign, he left Williamsburg—along with many other residents of the city—for the safety of Richmond.

A photograph (below), taken sometime before Duke of Gloucester Street was paved in the early 1900s, shows the house much as it looked before its restoration in the 1950s.

Union General George B. McClellan rode into the city the next day. "This is a beautiful town;" he wrote to his wife, "several very old houses and churches, pretty gardens. I have taken possession of a very fine old house which Joe Johnston occupied as headquarters. It has a lovely garden and conservatory. If you were here, I would be much inclined to spend some time here."

McClellan dallied for nearly a week before leaving to join his troops as they marched toward Richmond, the Confederate capital. Union pickets ringed Williamsburg, a wartime town under military jurisdiction. Citizens were required to take oaths of loyalty, censors examined each piece of mail, no one could pass through the lines without permission, and food was scarce.

Colonel Campbell, provost marshall for the Union forces, occupied the Palmer House on September 9, 1862. Major Christopher Kleine succeeded Campbell, and David Cronin, a captain of the First New York Mounted Rifles, succeeded Kleine.

Cronin was well educated and trained in Europe as an artist. He produced a series of pen-and-ink drawings of occupied Williamsburg. The young officer appreciated the old buildings, and wrote of his quarters:

The Palmer House apples must be frequently replenished; squirrels and birds find them a ready source of winter snacks.

A few stone steps with an iron railing at the front door gave ready access to the broad sidewalk and the width of the street afforded ample standing room for the horses of the officer and their orderlies. These facilities added to the convenient stables in the rear entered through a side gate below the garden, make up all that could be reasonably required for the headquarters of an army in the field.

As an outpost on the front, Williamsburg was prime real estate for spying and intelligence gathering. For nearly two years, it was the closest city to Richmond in Union hands. Cronin said the town was an observation post for both sides.

Williamsburg's African-American residents figured prominently in the espionage. Exempt from the loyalty oaths and restrictions imposed on white Confederate sympathizers, some carried Confederate messages freely. Others secretly served the Union cause. Cronin discovered after the war, to his chagrin, that three servants who cared for him graciously at the Vest house carried Union military secrets to their Confederate masters.

Cronin sympathized with the non-combatants of the city and attempted to prevent pillage by the occupation garrison. Even so, the war took its toll. "The expression on the faces of Williamsburg people was one of indisputable hatred and contempt," Cronin wrote. "If ever there had been the least spark of Union sentiment in the place, that spark was wholly extinguished before the war was long in progress."

Cronin re-visited the city in 1901. Now in his 60s, he saw a town no larger than the home of the 1,500-people he governed in 1865. There was a railroad and a hotel, but there was something unchangeable about the city. "An air of venerable prestige pervades the town," Cronin wrote, "and this will always render it attractive and inspiring to lovers of history."

Jim Bradley a long-time Colonial Williamsburg public relations writer, contributed a story on the re-opening of the Gold Course to the Summer 1998 journal.

Visit our Christmas section (will open in new window).