Online Extras

Zoom in on Printed Documents

Williamsburg’s Printing Office sent newspapers, almanacs, books, and other printed matter throughout the Virginia colony.

Colonial Williamsburg

An early photo shows an ox cart on Duke of Gloucester Street passing by the Printing Office building before it was restored.

From left, Will Damron, Kate Kovach, and Dennis Watson, as Alexander Purdie, in the Post Office store, with reproductions for sale.

Colonial Williamsburg

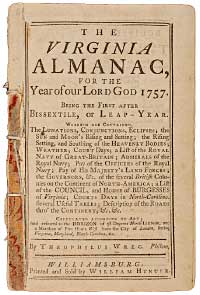

Weather, road conditions, government business, court dates– all were available in an almanac from printer William Hunter.

Colonial Williamsburg

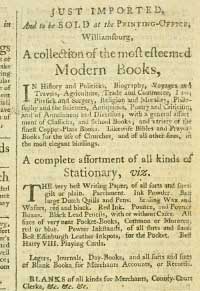

The Williamsburg Printing Office sold everything from novels and Bibles to ledgers, pencils, pens, paper, and playing cards.

Staying Connected before the Age of the Silicon Chip

by Susan Berg

Increasingly, people communicate and find their their information and goods through the Internet. They use personal computers and smart phones, and they like to keep in touch with family and friends, follow the news, maintain a calendar, and buy products and services. Whether they are getting directions, checking the weather, reading an ebook, or writing a blog, more and more they seek and store their information in a digital format.

How did eighteenth-century Virginians communicate and stay informed? How did they know when to plant tobacco and grain or where to purchase certain goods? Was there a colonial equivalent to today’s email and ecommerce and to social networks like Facebook and MySpace? What was the Virginia counterpart to such websites as Amazon.com where colonists could buy books and goods, or to the blogosphere, where they could voice their opinions? The Williamsburg Printing Office served all those functions.

Virginia’s first printer, William Nuthead, was driven from the colony by the General Assembly after an aborted attempt to set up a press in Jamestown in 1682. Twelve years earlier, Governor William Berkeley had written:

I thank God, there are no free schools nor printing, and I hope we shall not have, these hundred years; for learning has brought disobedience, and heresy, and sects into the world, and printing has divulged them. . . . God keep us from both!

It took almost fifty years more to permanently establish a press in Virginia. Great Britain’s largest colony was among the last to support a printer.

In 1730, the General Assembly invited Maryland’s William Parks to come to Williamsburg to print the laws and journals of the House of Burgesses. Parks was an able artisan and a savvy businessman. In addition to printing a collection of the acts of the General Assembly, not long after arriving he began to publish short pieces intended to flatter the current governor, Alexander Spotswood, and to shore up the support that would allow him to safely expand his operation and explore business opportunities without fear of expulsion.

Within ten years, Parks had supplemented his annual salary for publishing the laws by printing a weekly newspaper, an annual almanac, and monographs.

Starting on August 6, 1736–a Friday–subscribers could read the news from Virginia, other colonies, and abroad–albeit not in the most timely manner–in weekly issues of the Virginia Gazette. Parks’s Gazette also provided a forum for readers to express their opinions. When one sees the frequency of these short commentaries, Virginia seemed to be populated with voluble eighteenth-century bloggers who wrote on subjects from politics to love. They adopted pseudonyms appropriate to the times with contrived versions of classical names such as Criptonimus and Philanthropos or satirical sobriquets such as Helena Littlewit and Timothy Touch-Truth.

From Parks’s Virginia Almanack, farmers could determine when to plant, as well as gather such practical information as the times and places of fair days and distances between cities. At 7 1/2 pence, it was priced to be affordable, though some customers purchased deluxe editions with blank interleaved pages to keep journals and appointment calendars.

In 1742, Parks opened a bookstore at the Printing Office. Printing a book was an expensive enterprise because of the scarcity of paper, ink, and especially type. Parks was probably addressing a demand from his readers when he printed, and later reprinted, John Tennant’s 1734 work, Every Man His Own Doctor: The Poor Planter’s Physician, and the first cookbook printed in the English colonies, E. Smith’s 1742 volume, The Compleat Housewife.

Professors and students at the College of William and Mary bought books, but so did other Virginians. Parks imported most of his titles from England and other colonies. Through advertisements in the Gazette and Virginia Almanack, colonists learned they could purchase practical manuals, or such popular religious tracts as Richard Allestree’s The Whole Duty of Man.

He diversified by selling such printed forms as indentures, land patents, and tobacco notes–the paper Virginians used for legal and business transactions, and currency–and established a Virginia postal route. Operating from the Printing Office, the postal service expanded his market and the demand for his products beyond Williamsburg to the farthest regions of the colony. Now, when customers visited his shop, they could send and receive mail while purchasing newspapers, books, pamphlets, and forms.

With such initiatives, Parks created a market for information and built a customer base apart from his seminal client, the General Assembly. A business created to print the laws of the land had been transformed into an all-purpose bookstore, post office, stationer’s shop, and publishing house. By the time Parks died in 1750, his establishment supported operations that rivaled presses in colonies such as Massachusetts that had been in business for more than a hundred years.

How many people were customers, and what did they buy?

For years, the prevailing view among historians was that only Virginia’s landed gentry pursued reading or books, a theory supported by reviewing estate inventories, which showed some gentlemen developing libraries.

A study of advertisements in the Virginia Gazette attempted to identify what kinds of books were most popular. Advertisements, however, provide an incomplete picture of the culture, showing what was available, but not necessarily sold and read.

Two of Parks’s successors provide the best source with which to analyze the market and determine demand, discover who the customers were, and identify which titles made the colonists’ best-seller list.

William Hunter was in charge of the Printing Office from 1750 to 1760, and Joseph Royle operated it from 1760 to 1766. Though not as entrepreneurially adventurous as Parks, they sustained the operations he had begun.

Like other colonial shopowners, Hunter and Royle recorded sales in account books. Business transactions in the form of daybooks for the years 1750–52 and 1764–66 survive. Kept to track sales and show areas of profit or loss, they provide more insight into the print culture and reading habits of colonial Virginians than the printers intended.

Hunter’s books show individual credit transactions and a monthly summary of cash sales. His apprentices or journeymen recorded the sales in a daily waste book and transferred the transactions into a monthly ledger, and Hunter reviewed the figures, occasionally indulging in whimsy by sketching a “smiley face” underneath his initials. Royle, who became master of the shop upon Hunter’s death, recorded only credit transactions. He tracked them more carefully, however, noting whether they were made by the buyer in person or indirectly through a friend, relative, agent, or by letter.

Analyzing the sales alongside such contemporary sources as the Virginia Gazette, surviving eighteenth century York County records–the dividing line between eighteenth-century York and James City Counties ran along Duke of Gloucester Street–and other references, we can identify who the customers were, where they lived, and what part of society they represented.

For Hunter, the largest group was from Williamsburg and neighboring James City County and York County at 38 percent. Customers from the greater Tidewater area up to the Fall Line near Richmond made up almost 35 percent. Almost 30 percent of customers hailed from the Piedmont, Shenandoah Valley, and Blue Ridge Mountains. Fourteen years later, in 1764, Royle posted a similar geographic distribution for his clients. The Printing Office on Duke of Gloucester Street was serving the entire colony.

Though Royle’s sales covered the same geographic area as Hunter’s, the number of customers in his market grew 53 percent larger. This increase was greater than the growth rate of the population in that period, suggesting that Virginians were developing an appetite for books and information.

Daybook sales for Hunter and Royle show that Virginia customers included doctors, merchants, lawyers, small planters, women, tavern keepers, craftsmen, and College of William and Mary professors and students, in addition to burgesses, council members, justices, landed gentry, and clergy. Although almost 50 percent of customers came from the upper classes, the rest of society also shopped at the Printing Office.

Less than half of Royle’s sales were made to buyers visiting his shop. Busy colonists would order their books and other Printing Office needs through a letter or note or would send their sons and other relatives to purchase them. Women were occasional customers, and slaves often came to place and fill orders for their masters. Thomas Jefferson sent his slave Jupiter to the shop to buy books for him, and Governor Francis Fauquier and planter Landon Carter sent their slaves on similar errands.

In this manner, Royle recorded not only who patronized his shop each day but the elements of Virginia society meeting there daily. For example, Jefferson visited the shop thirty times in the two years between January 1764 and January 1766. He was not only purchasing books but also picking up letters, buying stationery, or settling his account. The Printing Office was a popular place, and on a typical day Jefferson, the young law student, could have rubbed elbows with Richard Bland, burgess from Prince George County; Robert Carter Nicholas, treasurer for the colony; and Speaker of the House John Robinson. He could have conversed with Priscilla Dawson, the widow of the Reverend Mr. Thomas Dawson, College of William and Mary president, who was buying a prayer book, or greeted such merchants as James Tarpley from Williamsburg and Alexander Cunninghame from King George County. He could have waited for the post rider along with craftsman Edward Charlton and wigmaker Robert Lyon, and quite possibly stepped aside to let tavern keeper Jane Vobe, who operated the ordinary behind the Capitol, buy six dozen packs of the best playing cards for her customers.

Advertisements list hundreds of titles available at the Printing Office. The daybooks show sales of ten thousand volumes. Readers could select histories, practical manuals, or such literature as Jonathan Swift’s The Tale of a Tub and John Milton’s Paradise Lost, as well as contemporary editions of classical authors.

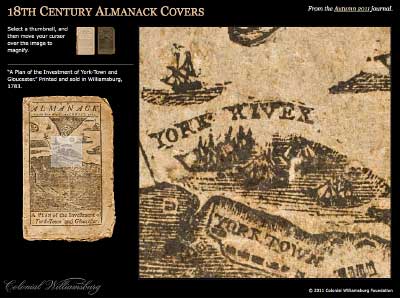

The most popular book was the Virginia Almanack. Hunter and Royle each sold several thousand single copies and made gross sales to merchants in the Piedmont and Shenandoah Valley. This handy calendar pocketbook could be found throughout the colony.

Sales of other books show a changing focus in what Virginians were interested in reading. From 1750 to 1752, after almanacs, the next most popular subjects were, in order: religious works; schoolbooks such as grammars, spellers, and dictionaries; the classics; and literature.

Fourteen years later, from 1764 to 1766, political pamphlets had replaced religion as the top seller, but grammars and other schoolbooks, such as Thomas Dyche’s Spelling Dictionary, remained the next most popular subject, followed by literature and the classics. Current politics, specifically controversies over taxation issues with the clergy and the Stamp Act, engaged colonists' attention, and sales of locally printed pamphlets on these issues, The Rector Detected and The Colonel Dismounted, for example, soared.

As craftsmen’s desire for learning increased, they purchased schoolbooks for themselves and their children to better their station. While reading classical authors like Ovid and Phaedrus remained the hallmark of a gentleman’s education, Virginians also spent their leisure indulging in contemporary literature, and sales of novels surpassed those of the classics. One of the most popular novels sold was John Cleland’s Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure, better known as Fanny Hill.

Following Royle’s death in 1766, some influential Virginians decided one printing office could not meet their needs. Lieutenant Governor Fauquier said in a letter he wrote to the Board of Trade in London, “. . . as the press was then thought to be too complaisant to me, some of the hot burgesses invited a printer from Maryland. . . .“

By the end of the year, Alexander Purdie and John Dixon, and competitor William Rind, operated presses on the Duke of Gloucester Street. In less than ten years there would be a third press in Williamsburg.

There had been an information revolution in North America’s most populated colony, one that, by supporting the exchange of news, facts, opinions, and thought, helped foster the armed revolution six years later.

Susan Berg former director of Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, contributed to the June/July 1999 journal "Make Me a Good End," an article about lawn bowling.