Merchants Square Meets Quinlan Terry

by Edward Chappell

Richard Binley guides a sandstone block on the scaffolding in Merchants Square. Photo by Ed Chappell

Three-hundred-pound stones float in overhead like dying balloons. Stonemasons Richard Binley and Scott Hilton reach up and ease the blocks down onto a thin bed of lime mortar, making almost imperceptible hand signals somehow visible to the crane operator, who gently pivots the stone hanging from a steel cable. The men unbuckle each stone, align it with a taut string, and check the face and edges with hand levels. Twelve blows from a rubber hammer bring the stone an even eighth of an inch away from its neighbor, which happens to be discreetly carved with the date 2002.

As esoteric as it seems, this exercise is no more demanding than brickwork under way nearby, where Raymond Cannetti pieces together an arch made of 144 bricks, all but twenty-four visible and so carefully shaped that they fit together with putty joints the width of a knife blade„a thin knife blade at that.

The work is part of a remarkable project to expand Merchants Square, substantially but judiciously, using plans developed by the English architect Quinlan Terry. Supported by a donation from Richard and Shirley Roberts of Virginia Beach, Virginia, Terry's work is a thoughtful response to the existing character of Merchants Square. The square itself is a remarkable piece of American architecture and twentieth-century design history. It is also Williamsburg's principal downtown shopping area.

Precisely how Colonial Williamsburg would develop after John D. Rockefeller Jr.'s initial decision to restore parts of the town was far less predictable in 1927-30 than it now appears. It was not until the early 1930s that many decisions were made about how restored buildings would be used—for museum exhibitions, college classrooms, restaurants, and the like—or how many there would be. Indeed, it was only after the early building and landscape restorations attracted public acclaim, and Rockefeller himself found the work so satisfying, that he committed to restoration of nearly the entire town.

Yet Rockefeller, the Reverend W. A. R. Goodwin, and the Boston architectural firm of Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn had begun to think about what is now called Merchants Square as a new business district for Williamsburg as early as 1927. Goodwin was an Episcopal minister who inspired Rockefeller's involvement in the restoration, and he had hired Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn to turn his ideas into explicit forms. Businesses were then spread all along Duke of Gloucester Street, most of them clustered near Market Square and the College of William and Mary.

The westernmost block of the main street, facing the college, was a part of the eighteenth-century town, but only a fragment of one early building survived there above ground. Based on the concentrations of early buildings, a decision was made to focus initial restoration on the college buildings themselves and along the rest of Duke of Gloucester Street, with the new commercial neighborhood located between them.

Occasionally the decision has been questioned, given the extent of preservation and restoration that took place. But the choice was carried out so thoroughly and artistically that there is little value now in second-guessing it. Approaching its seventy-fifth birthday, Merchants Square has taken on national historical importance of its own as one of the first fully planned shopping areas in the country.

Some of the earliest designs from the brainstorming in 1927-28 are admittedly frightening. The influential Boston landscape architect Arthur A. Shurcliff produced bird's eye views suggesting Duke of Gloucester Street could be split into four double lanes for cars and diagonal parking separated by green strips. Commercial buildings would be recessed and aligned toward the parked cars.

Williamsburg's Methodist congregation had recently built a sizable brick church in the northwest corner near the college. Shurcliff and his colleagues suggested adding a second church to face it from the south, creating an impact like two papal monuments marking the entrance to a Roman piazza. Another scheme called for a large hotel complex wrapped around a block-sized courtyard immediately south of the street. These initial concepts would have made sense if the object had been to create a formal and boldly structured new town, but clearly they were overdone in relation to the delicate qualities of the Historic Area.

By 1929 Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn had settled on a more thoughtful but still lively design for Merchants Square distinctive and sympathetic to the Historic Area. Merchants Square was to include just over one block containing the post office, a bank, a movie theater, and stores that matched the diverse scale of the town's eighteenth-century buildings. They were to be arranged, however, in a more picturesque manner, with varied setbacks and in clusters of attached structures unlike the primarily freestanding colonial buildings. In a happy and influential move, most parking was soon shifted to the interiors of the blocks. Beyond were modest services like Ayers Garage for motoring residents and travelers.

Rockefeller and his architects shared a sophisticated appreciation for the character of the original buildings, and they understood the value of creating subtle distinctions between these and the new commercial enclave. A relatively small firm that had specialized in scholarly design of New England buildings, Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn were well-suited to Williamsburg's restoration. From 1927 to the early 1930s, their Williamsburg staff developed a design grammar for the Historic Area based on very precise observation of early buildings in eastern Virginia. For Merchants Square, they employed a similar degree of well-comprehended, literal detail drawn from a much more eclectic range of sources. Talented draftsmen like John Barrows, George Campbell, and Thomas T. Waterman focused their energies on the Tidewater environs of Williamsburg but retained a freewheeling interest in what they saw as the broader spectrum of the English diaspora. The fruits of this interest are seen in hundreds of measured drawings prepared for Merchants Square, with the same level of detail lavished on designs for wrought-iron gates to the vault and tellers' cages of the bank on the square's east end as on the iron fences at the Governor's Palace.

The designers cited eighteenth- and nineteenth-century neighborhoods in mid-Atlantic communities like New Castle, Delaware, as inspiration for Merchants Square, though the sources were much more widespread. Many of the features are frankly English, such as a greater variety of glass shop fronts than would be found in any early Virginia town. Some brick buildings, like the present Williams-Sonoma store, are inspired by both English and Chesapeake prototypes. Perhaps more surprising, the College Shop, with a brick principal story and an overhanging wooden upper floor carried on Tuscan columns, draws on early house-store combinations in market towns of the British Caribbean.

The Craft House in Merchants Square, occupied by an A & P grocery from 1932 to 1954, seems inspired by the seventh of Jefferson's ten classical pavilions housing faculty beside the Lawn at the University of Virginia and by post- Revolutionary resort buildings in western Virginia, certainly edifices one would never expect to encounter on the main street of Williamsburg. Designing some buildings in a post-eighteenth-century style was intentional, as at the Williamsburg Inn, a second group of buildings that are sympathetic to while looking slightly different from the adjacent Historic Area. In both cases, the intent was to create subtle cues for the observant visitor or resident and to avoid diluting the character of the Historic Area.

As rich a jambalaya as this seems, the result is visually coherent and successful, and has inspired distant copies of varied quality. The square was essentially finished in 1932, with the movie theater opening the following January.

There have been some peripheral additions, like the 1940 post office on Henry Street, now Everything Williamsburg, and its 1962 successor one block south, now the Henry Street Shops. The nature of the commerce has also evolved, changing most rapidly in 1955, when many of the locally oriented stores moved to a shopping center developed by Colonial Williamsburg a mile or more west of the Historic Area. It is no longer possible to buy a frozen chicken or a cast-iron stove in Merchants Square, though one can certainly enjoy an excellent meal or find a good book there.

Even the name has evolved. First identified as "shops," and "the business block," the area was not christened Merchants Square until 1964, when George Wright, Colonial Williamsburg's liaison with the stores, suggested it. Ten years later, traffic and parking were forbidden in this section of Duke of Gloucester Street.

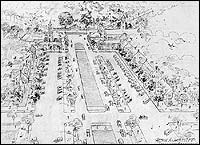

Bird's eye conception of Merchants Square, drawn in 1928 by William Campbell for Arthur A. Shurcliff. The traffic shortcut through the college yard at bottom left, the proposed church on the right, and parking lanes along Duke of Gloucester Street were never executed.

A major opportunity for expansion appeared when the somewhat awkward Methodist Church opposite the college yard was demolished in 1981, long after its congregation moved to larger quarters on Jamestown Road. In 1999 the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation began planning use of the site colloquially called "college corner" for the first front-stage addition to Merchants Square since 1932. The square's businesses would benefit from the presence of additional stores serving visitors and townspeople, and the site needed buildings to visually define the end of the principal street.

Such opportunities naturally present demanding questions. How should the buildings look? What should be their idiom, their style? Openly contemporary designs like the 1957 Visitor Center and its recent additions are very well planned but would seem inharmonious in this location, while postmodern plays on early Williamsburg generally fail to transcend shallow humor. Clearly the additions had to respond to the existing Merchants Square townscape and the college yard, and they also shouldn't be copies.

The truth is also that much colonial revival or traditional architecture built since the 1930s has been eminently forgettable, relying more on diluted or, conversely, bloated repetition of old designs than on thoughtful use of visual grammar.

What were needed—planners told themselves—were buildings in a literal historicist idiom that would have both dignity and some respect for the college yard and Duke of Gloucester Street, but would be as fresh and imaginative as Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn's buildings had been when they first surprised observers over seventy years ago.

Colonial Williamsburg looked worldwide for available designers and, after energetic debate, settled on Quinlan Terry, a highly regarded and sometimes controversial architect who heads a small firm in Dedham, England, called Erith and Terry. Terry's senior partner, Raymond Erith, died in 1973 after decades of quixotic effort to offer England an alternative to single-minded modernism. The firm designed a large retail and office complex facing the Thames in Richmond on the upriver side of London. It was the consistency with which the firm had produced interesting buildings more than any particular project, though, that led us to Dedham.

Terry joined Erith in 1962 and has increasingly found clients willing to support his own demanding standards of design. In most ways those standards parallel Colonial Williamsburg's architectural obsessions: concern with the character of details, careful selection of materials, relevance of the context, and precise execution.

One of the interesting elements of the present design work has been how the architect and his clients have nudged each other forward. Terry is more concerned with expressing the true size of the new retail spaces than were Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn, who were willing to hide the 534-seat Williamsburg Theatre, now the Kimball Theatre, behind a modest three-bay brick faade. Likewise Terry is committed to load-bearing masonry exterior walls, though earlier Merchants Square designers were content to slide a steel beam under a second-floor wall if it contributed to outward visual harmony.

Acknowledging the eclectic architectural character of Merchants Square, Colonial Williamsburg sought new buildings recognizably designed by Terry. But in the words of Cary Carson, vice president for research, we wanted "buildings that look like Quinlan Terry in Williamsburg."

This union of contextualism and the artist's vision is illustrated by the southernmost of the four buildings, front and center on the old church site. The site is among the most visually important in town because it marks the western end of Duke of Gloucester Street, where it intersects at a right angle with Boundary Street. Just at this point, Francis Nicholson's 1699 town plan connects what are now called Richmond and Jamestown Roads at acute angles flanking the college yard.

The dramatic arrangement has survived into the modern age at this point, much like French engineer Pierre L'Enfant's ceremonial intersections have in traffic-choked Washington, D. C. Terry saw a need for the corner building to face south—toward the main street—and west, where it would be visible to everyone entering town on Richmond Road.

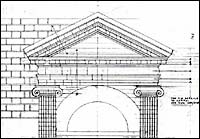

His solution, as bold as Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn's University of Virginia pavilion and resort borrowing, is a square building with an arcaded first floor and a cupola on the roof, reminiscent of early markethouses and Charleston's more elaborate 1767 exchange. The building is sixty-four feet on a side, expressing the scale of the space it encloses. With the use of pedimented pavilions that push forward at the center of both faces, however, the walls are broken into segments somewhat like three narrow buildings in a row.

Materials emphasize the wall divisions, with all stone used for the principal level of the projections but only to trim brickwork on the receding walls. Stone was used very sparingly in eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century eastern Virginia, most dramatically on late colonial houses near the Rappahannock and Potomac Rivers. In Williamsburg it was primarily used outside for expensive and durable steps, like those at the Courthouse, Governor's Palace, and John Blair's house a half block from Merchants Square.

As Terry proposed the use of stone trim and the design discussion developed, the Williamsburg staff suggested combining a dark red-brown sandstone with relatively dark red brick like that on the Courthouse and Bruton Parish Church's tower. English red-brown sandstone had been used at the Courthouse and probably the Public Hospital. The masonry choices would help tie the building to the town, and using dark stone would soften the contrast between the two materials, making it more compatible with the monochromatic masonry of the college buildings. It was a choice Terry had not made in his previous buildings, but he enthusiastically embraced it.

Next door to the north is a much smaller five-bay wooden building. It might be easily mistaken for an 1800 house in almost any Virginia town, except that Terry employed faceted window bays, an English vernacular technique for increasing light and visibility without recourse to traditional shop windows. The two sources combine seamlessly.

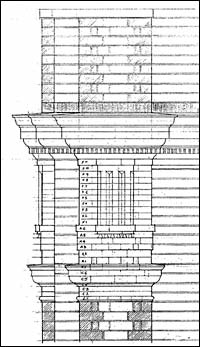

Elevation of the south block about 1929. The building on the left is a preliminary version of the present Craft House, Fat Canary Restaurant, and Cheese Shop.

The third building, at the northwest corner, is more emphatically English, though it, too, has connections with the Chesapeake region. It resembles a substantial two-story brick house with sizable shop windows facing west and north. The long walls are framed by tall brick pilasters at the corners, rising to carry a cornice that, on the street side, is beautifully made of the specially molded and cut brick that Raymond Cannetti lays with knife-blade joints. A recessed niche constructed of the same material punctuates the middle of the wall and breaks through the cornice.

Eighteenth-century Virginians used this sort of specialized brickwork to render classical details in red to dark orange hues, most grandly for the door surrounds at Christ Church in Lancaster County, and Rosewell, now in ruins, on the Gloucester side of the York River. Closest to Merchants Square are the frontispieces on Carter's Grove and the 1748 Secretary's Office beside the Capitol, as well as Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn's Peninsula (now SunTrust) Bank.

Two-story brick pilasters were used on Middleton's Tavern in Annapolis and a handful of houses in eastern Maryland. Though such Chesapeake examples have contributed to the design discourse, Terry's main source has been two buildings in his own village of Dedham. He has long admired these expressions of tradesmen's classicism in East Anglian villages, but this is his first borrowing. He considers it East Anglia's gift to Virginia.

Rounding the corner, one finds the north- and east-facing fourth building, appropriately eclectic as a termination for the ensemble. It has the general aspect of a restrained Regency house around London or the stylish versions Benjamin Henry Latrobe designed for Richmond clients in the 1790s. It is, then, an interesting variation on the post-Revolutionary idiom used elsewhere in Merchants Square and at the Inn.

Terry is attentive to such stylistic connections, but he is not bound by them. We considered a wide range of handmade brick and built numerous test panels before selecting what seemed the best choices for each building. We were intrigued by the possibility of using small, relatively light tan brick of a variety found on early archaeological sites in Virginia and Maryland. I suggested we consider them for limited use as foundations and chimneys on the wood-walled building. "Oh, no, Ed, let's use them for the Regency building," Terry responded with a more artistic than prescriptive taste.

The question of how to design appropriate additions to historic neighborhoods—often called "conservation areas" in Europe—has been a subject of vigorous argument around the world since the 1960s. Merchants Square presents a case in which the neighborhood itself can be viewed as thoughtful infill, designed to serve modern retail needs for the town in the early stages of a now-famous restoration.

Colonial Williamsburg intends the current additions to maintain and enhance the architectural unity that makes Merchants Square an inviting place to shop, see a film, have a meal, and enjoy good design. They are meant to respect what surrounds them, in the Historic Area and the square. But they are also meant to have panache, just as our predecessors would have expected.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

The architects Perry, Shaw and Hepburn drew this map for the crucial 1927 meeting in New York between Reverend W.A.R. Goodwin and the then-anonymous donor John D. Rockefeller, Jr. The detail shows the College of William and Mary to the right (west), with Merchants Square just to the left (east).

Click image to enlarge | View detail

Second aerial view by William Campbell for Arthur Shurcliff's office, c.1928, with then-standing Methodist Church at right rear, where Richmond and Jamestown roads meet Duke of Gloucester Street. Such drawings reveal the influence of formal urban planning like that for Chicago's 1893 Columbian Exposition and 1901-02 McMillan proposals for Washington, D.C., ultimately gentled in Williamsburg by the small scale of the Historic Area.

Edward Chappell, director of architectural research, participated in planning the additions to Merchants Square.