Palace Days

Recollections of Dismantling the Most Beautiful Rooms in America

by Graham Hood

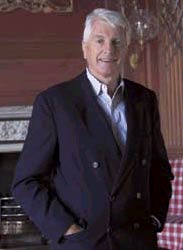

Dave Doody

The author in the hall of the Governor's Palace.

Spring of 2001 is the twentieth anniversary of the refurbishing of Colonial Williamsburg's Governor's Palace. Since its reconstruction as an exhibition building in 1935, the Palace had been a Mecca of taste and inspiration for millions of Americans. Yet in January, 1981, the building was closed for architectural modifications and for a new furnishing scheme. After three intense and feverish months it reopened with a very different look, a new interpretation, much fanfare, and a certain trepidation.

The changes were major. They had been in preparation for about three years and entailed a fresh look at old evidence; countless, deeply probing questions; and a refusal to take anything at face value. Beginning as a curatorial initiative, the project ended up involving much of the great array of Colonial Williamsburg’s educational forces. Made possible by a generous grant from the Rockefeller Brothers Fund, the changes have been seen in retrospect as having had a major influence on this country’s historic houses and how they represent themselves, as well as on the subject of the period room.

The Governor's Palace refurnishing was for me, as chief curator during this period, a public duty that also became a private obsession. As it unfolded, I saw it involve extraordinary zealotry, skills, dedication to historical research, and passion—the kinds of things that I believe John D. Rockefeller Jr. dreamed his work at Williamsburg would foster. It was, as well, not a little hazardous on the diplomatic front, a story that has not hitherto been told.

I first saw Colonial Williamsburg in 1968, when I came to speak at the twentieth Antiques Forum. I was struck by the size of the place, and was charmed by its streets and greens. But everything looked . . . well, so new, except for the period rooms filled with antiques. To my mind then, these rooms suggested that the eighteenth-century residents had lived rather grandly. Along with two other young forum speakers, Jonathan Fairbanks and John Kirk—who have since written numerous books on eighteenth-century America—I stood one afternoon in the Governor's Palace dining room, contemplating the clever handiwork of Colonial Revival taste. Then Kirk burst out, "There's no way in the world it can have looked like this in the eighteenth century!" Fairbanks and I looked at each other and concurred—youthful asseverations, undoubtedly, but they proved to be right.

Dave Doody

The Governor's Palace, dressed out for Christmas shows the trim smartly painted white, as it should be.

Two years later I found myself again at Colonial Williamsburg, this time being interviewed by President Carl Humelsine for the job I would have for twenty-seven years. When the subject turned to the Historic Area buildings, Humelsine advised me to entertain no notions of creating "a Graham Hood taste in period rooms at Williamsburg" as a sequel to the chief curator John Graham taste of the 1950s and 60s.

That was fine with me, since I didn't think I had any taste in that area anyway. Humelsine said that the rooms at Williamsburg were widely admired and told me he had no intention of seeing them dismantled willy-nilly.

Humelsine was not against change, but he insisted change be based on research, not taste. At the time I thought that was fair, and it proved to be an excellent lesson. Humelsine was a great boss and a great man, opinions time has deepened.

I arrived believing that eighteenth-century English paintings and prints could tell us a lot about what rooms looked like two centuries before. We expanded our archive of them and studied them more deeply, gleaning insights into life as it was being lived. This seemed to me to be what period rooms could best convey to staff and visitors alike.

Our first refurnishing project was the Raleigh Tavern. In two weeks, in November, 1972, we changed this, the first exhibition building, from a place suggestive of an old fashioned club to something more like an eighteenth-century tavern. Our interpreters loved it, Humelsine approved, and we gained confidence to examine other buildings.

In the 1970s we brought to Williamsburg most of the curator-scholars doing innovative work on eighteenth-century houses. The Antiques Forum provided us with the opportunity—and, as importantly, the budget.

Colonial Williamsburg

Lord Botetourt, a copy of a wax protrait of the 1760's by Isaac Gossett, preserved at Shirley Plantation for two centuries, now owned by Hill Carter.

Many came from England. We are indebted to such scholars as Roy Strong of the National Portrait Gallery, London, who created period tableaux for exhibits he directed there; Peter Thornton, of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, doing cutting-edge work at Ham House; Geoffrey Beard and Helena Hayward, who were deeply involved with the subject as they wrote important monographs; Christopher Gilbert of Temple Newsam House, Leeds, who was revitalizing that great house and putting the finishing touches to his landmark publication on Thomas Chippendale; Mark Girouard, who shared with us the research embodied in his Life in the English Country House; and John Cornforth of Country Life who helped us tirelessly.

They buoyed us with their enthusiasm, generously gave us information and advice, made us sure we were on the right tracks, and kept in touch with us afterward. They took us more deeply into the world of eighteenth-century inventories and interiors than we had gone. I cannot over-emphasize the value of their contributions.

Gilbert, I think, helped us most. He came for a month on an National Endowment for the Humanities grant in 1974, when I was beginning to get immersed in the Botetourt inventory—the compendious list of items in the Governor’s Palace, taken in 1768 on the death of Lord Botetourt, the first full governor to live in it. I wasn't obsessed with the inventory as I would later become, but I was beginning to see how complex, detailed, and bursting with information it was.

I showed it to Gilbert and he agreed. We pored over it for hours. His experience with inventories of the British houses for which Chippendale had supplied furniture, as he was looking for original pieces and their original contexts, helped us hugely. Gilbert taught us much about the subtleties of hierarchy in English houses, from the grandest to the lesser, from the state rooms and their furnishings to the humble quarters of hirelings and the few things they had.

He also spotted links between documentary references in Williamsburg and contemporary England. He pointed out where certain kinds of objects would have stood in certain rooms in England, and explained things that, frankly, we didn't know. Some of these were so simple we frequently found ourselves saying, "Oh, yes, of course," and thinking, "Why on earth haven't we thought of that before?”

Later, Gilbert persuaded dealer Simon Redburn to get involved with our project. Redburn turned up all kinds of small, unpretentious, and right objects, often for a few hundred dollars. We believed we were matching the object and the evidence as closely as we could. That was important. Never before at Williamsburg had the curators zeroed in so fanatically on the precise object that the inventory listed, the precise origin, the precise date.

Colonial Williamsburg

copy of the inventory of Botetourt's estate, showing the numerous corrections and additions. The original is in the Library of Virginia at Richmond.

In all this we were aided by Wallace Gusler's trailblazing work, in the 1970s, on Virginia furniture, as well as by Gilbert's discoveries of contemporary English furniture of the less-than-very-grand kind, of the nice-but-not-spectacular kind. Together, the minds of these two scholars pushed us toward the focused, particular choice of furniture to suit this particular place at this exact time. The Williamsburg inventories we were studying were not new or hitherto unknown. They had been available to read fifty-five years before, when the Restoration was getting started. What we were doing, and getting better at all the time, was reading them more carefully and more closely than they had been read before, with more scrupulous attention to the detail of the text.

And not just the Palace inventory, but all of the Williamsburg inventories. Some of them were not divided by rooms—they were just cryptic lists. But we learned to decode those lists, dividing them into probable room clusters by the kinds of things that were grouped on paper, and by this method to suggest a sequence of rooms. We began to learn what plausible sequences of rooms were. Then we realized that objects listed next to or near each other on paper could suggest physical proximity in the room. It sounds surpassingly simple now, but it was breakthrough stuff then.

In the meantime we were changing almost all the rooms in the Historic Area. With ever-increasing subtlety, I think, we were matching better the kinds of furnishings with the building and time period and the sorts of persons we were dealing with, from modest tradesmen to rich planters. We used all kinds of ideas to suggest people living in these period rooms—unmade beds and socks hanging out of drawers were two. Taxidermied cats and dogs were, by consensus, ruled out. We tried to create, through things, the presence of servants and slaves. Some of these rooms were the most difficult to do, but among the most rewarding. About this time, Ivor Noël Hume created in the same spirit an evocative vignette at the Anderson House.

I inherited a wonderful curatorial staff, and added to it, but it took us four years to work up to making our first changes at the Governor's Palace—except for removing the regal Tompion clock, which had become a cause célèbre. Our changes were from upstairs to downstairs in style. Our research showed the Restoration architects in 1931–32 had. the evidence we did—but chose to install a family dining room in what was a butler’s pantry. In 1976 we changed the family dining room, replete with English royal silver and great ducal furniture, back to a butler’s pantry. Everyone, including Carl Humelsine, examined our evidence and found it indisputable. We made the changes in time for that year’s Antiques Forum.

Colonial Williamsburg

Prince of Wales shown the Palce in 1981 with Colonial Williamsburg President Charles Longsworth, and the the author.

All hell broke loose.

I think Humelsine felt like a Renaissance depiction of St. Sebastian—full of arrows. There was so much fuss from friends and supporters, who feared that we were about systematically to dismantle a Taj Mahal, that Humelsine put the brakes on further Palace changes for the time being. That made the curators more stubborn, for we knew we were right on the changes we’d made, and we knew that the rest of the building needed the same kind of treatment—unless, of course, Colonial Williamsburg intended to change its mission statement, and that was never an option. What Humelsine’s resistance did, though, was to send us back to the inventory, to read, to reread, to re-reread, dozens and dozens and dozens of times. And that was valuable.

The inventory is a rich text. It lists more than 16,000 objects in sixty-one living and working spaces. Then there are local tradesman’s accounts for the two years Botetourt was in residence, providing corollaries, as well as related letters. It’s a lot.

One afternoon I was reading the inventory again, for perhaps the hundred and umpteenth time—like reading a long and difficult poem, you must go through it many times in many moods to get through to the underlying meanings—and was looking at what was listed in a storeroom. Among the jars of raisins, the Turkey and India coffees and Congo tea and spices, the Negro shoes, the egg strainers, the balls of pack thread, the white macaroons, the ginseng and snake root, the Bristol soap and the hair powder, I realized that I was encountering paint brushes, carpet brooms, hearth brooms, cane brooms, cane whisks, hair dust brushes, bottle brushes, plate brushes, clothes brushes, shoe brushes, flat clamp brushes, and mops—twelve kinds of brushes, just for use in the house.

The thought came to me: “These twelve different kinds of brushes and brooms were used in twelve different kinds of real-life situations in different parts of the building, sometimes by different people. These simple words, identifying these humble objects, can tell us about a whole slice of life in this place. And the same applies to words that spell out chests of drawers, or different kinds of chairs, or silver cups, or china dishes, or tablecloths, or velvet suits. There’s a whole world in these words, waiting for us to understand it and set it free. This isn’t just objects, however wonderful; this is real life.”

Dave Doody

Author in Palace pantry, where many of the accounts, later found at Badminton, were kept in 1768-70

It was a magical illumination of brushes and brooms. I realized that all these black words on white pages, these descriptive, declarative words, represented a downstairs world as well as an upstairs world, an inside world as well as an outside world, a past world and a present world, just waiting for us to get inside.

I knew then that I could never leave it alone, that I had to do everything in my power to understand the evidence more and do all I could do to persuade Humelsine to go along. That wasn’t easy and I think we pestered him practically to death. A couple times I was sure he was going to fire me, and at other times he fulminated against the pesky, irritating, effete, and impossibly self-righteous curators. He was right, of course. He knew all about curators; he was a frustrated curator himself.

It took almost two years of persistence, stubbornness, tact, diplomacy, maybe a little sleight of hand, and some dumbness on my part. But by 1978 Humelsine was persuaded and had co-opted me to help persuade the board of trustees. Which I did. At least some of them. I remember a meeting when longtime trustee David

Brinkley, the broadcaster, came to me in the Supper Room and said, in his oracular style, “So . . . you’re going to dismantle the most beautiful room in America.”

Other comments from critics, within and without the Foundation, were legion and sometimes difficult to answer without exasperation. But the curators tried to explain our continuing research as clearly as we could. It was time consuming, but in the end I believe it paid off.

By late 1978 the Palace refurnishing had become a project, with funding and a tight deadline. In two years we had to assemble the furnishings and supplies we needed, make the changes, prepare the interpretive material, train the interpreters, and reopen the Palace as a brand new experience. The curators had been studying the inventory, the better to understand it, as much as I had. I got them together and said: “We’re going to work on this together, as a team. Individually, each of you knows a huge amount about your area of expertise, more than the rest of us put together. From now on we’re going to have regular meetings to discuss our progress on understanding the inventory as it applies to our separate areas. Each of you will also report regularly on your progress in identifying and acquiring objects to match the inventory for each room.

Hans Lorenz

Grand clock made for William III by Thomas Tompion was part of the Palace furnishings in the 1950s and 1960s.

“I shall ask each of you to show the rest of us how you know that the objects described in the inventory are the objects you are choosing for the particular rooms. I want you to explain carefully the process of logic by which you move from the words to the three-dimensional objects. “I am instructing you to excise totally from your vocabulary the words ‘must have been,’ or ‘might have been.’ Those words will not be accepted in our discussions or admitted as evidence. If you believe the primary evidence is unclear or inconclusive, then show us the logic of your comparative thinking.

“This is going to be a process of reason and deduction, not of taste or feeling. Anyway, we’re not dealing with our taste, we’re dealing with Lord Botetourt’s taste. We’re going to make this the most tightly argued and the most compelling refurnishing project that’s ever been done here.” The curators responded, and we had other Williamsburg resources on which to draw—historians and architectural researchers, archaeologists, and such craftsmen as Leroy Graves, Albert Skutans, Mack Headley, Pete Ross, and Doc Hassell, to name some. An example is the making and stringing of the tester and Venetian curtains for a state bed of the 1760 period that we needed for His Lordship’s Bedchamber. It involved four sets of curators and craftsmen working with wood, iron, brass, and textiles, and it took us further into the real object than most curators have traditionally gone.

Of course, we set ourselves an impossible goal. We couldn’t be irredeemably logical about everything. I couldn’t ignore that there is induction as well as deduction, instinct as well as logic, and that there is poetry as well as prose. And that all of these qualities, accompanied by myth, are as much a part of history as they are of life.

But I learned from my curatorial colleagues that there is no substitute for looking at the original. Never. You may interpret that literally or figuratively. This zeal led to discoveries. Some have been written about in previous issues of this journal, such as Wallace Gusler’s discoveries in remote locations of furniture with a solid Palace history, or my turning up in an English country house many documents that had been written by Botetourt and his servants while residing in Williamsburg. But one story that has not been told shows how a restless urge to examine the original can produce an insight that might at first seem tiny but that has big implications.

The original manuscript of the Botetourt inventory, now in the Virginia Library at Richmond, was transcribed almost a hundred years ago and has been available since. I asked for another transcription in the early 1970s, which was done from microfilm. One item—“8 stocker brackets” in the ballroom—we could not figure out. There’s not a lot of furniture listed in that large room, so every item is important. We checked every old and new dictionary we could lay our hands on and found nothing to explain what stocker brackets were.

One day Margaret Pritchard and Linda Baumgarten walked into my office and told me they’d just come back from Richmond, where they’d been reading the original manuscript. They didn’t think the word was stocker at all, but rather “stockoe,” in other words stucco. Stucco brackets. “Oh yes, of course!” The Oxford English Dictionary confirmed the variant spelling. Those brackets turned out to be important and elegant features of the ballroom.

Sometimes, though, zeal can produce equivocal feelings. When I came across Botetourt’s original account books and letters and with trembling fingers opened them, I realized they had, between their pages, the sand with which the original writers had dried their ink two hundred years before. I’m convinced that no one had opened most of them since they were audited in 1771–72 and filed away. I felt as if I were intruding, a voyeur, but after a few hours I was so excited by the mass of information they contained, my prurience left me.

I have to say that one of the most satisfying things about this discovery was how often it proved that our curatorial detective work of the previous two or three years had been right. Not every time, but often, and that was its own reward.

Colonial Williamsburg

Strong, then director of London's National Portrait Gallery, one of many supportive English scholars.

As a result of our work on the Governor’s Palace, we gained a new understanding of the decorative arts in this country, or at least in the southern portion and at the gentry level, in the decade before the Revolution. We also achieved a clearer understanding of the way the terse listings of an inventory can fill a building with life as well as with objects. We learned how spaces and things can amplify, and sometimes revolutionize, our perceptions of living at certain times in certain places.

We also learned that a microscopic textual analysis, arrived at by asking countless questions, and confirmed by comparative information, can increase understanding exponentially. And that there is no end to the questions.

I know that we didn’t ask, and therefore didn’t find, an answer to every question before we reopened the Palace. But I’m happy to say that questions are still being asked, and changes made—in the ballroom, for example, with the visually striking carpet. There are other examples, and there are questions curators of the future will answer, and we’ll all look at each other and say, “Oh . . . yes, of course. . . .”

Graham Hood was Colonial Williamsburg’s vice president for collections and museums and Carlisle H. Humelsine curator until his retirement in December 1997. His story, “My Obsession with the Governor’s Palace,” appeared in the autumn 1991 journal.