Online Extras

Of Follies Slideshow

HABS/Library of Congress

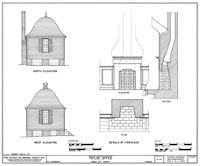

A Williamsburg folly. The Tayloe Office, with its medieval touches, spoke to the fancy and finances of its owner.

Colonial Williamsburg

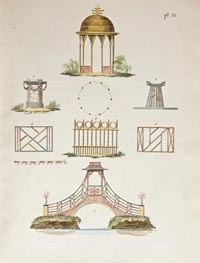

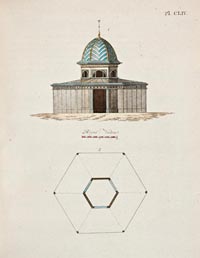

Follies’ forms and fashions roller-coastered from octagonal Chinese pagoda to round Moorish garden house, their owners’ whimsy and extravagance the only limits.

Michael Olmert

The Caryatids on the Acropolis' early nineteenth-century sisters at St. Pancras Church in London.

Michael Olmert

The neo-Gothic tower on a ridge in Worcestershire with turrets and parapets but also windows in the Georgian style.

Wikimedia

The thatched-roof folly where Edward Jenner administered the first smallpox vaccine in 1796.

Of Follies

by Michael Olmert

About 1755, next to his Williamsburg home on Nicholson Street, John Tayloe built himself a one-room office like no other. At least unlike any other building that survives from eighteenth-century North America. The small frame structure is a normal office with all the requisite windows, doors, and walls, and it has an S-shaped ogee-style roof, a bow in the direction of medieval architecture. Inside, its ceiling is plastered and groin vaulted, suggesting a small chamber in a castle or in a medieval chapel. You expect incense and chimes—smells and bells—in such rooms. But not in colonial North America.

The Middle Ages and the eighteenth century are kindred eras. The medieval Gothic details on the Tayloe Office were beginning to appear in pattern books published for builders, carpenters, and furniture-makers. This little building fits easily amid the Georgian confidence of Williamsburg’s architecture. It hints at a revered and shared medieval past. The triumph of the pointed arch and interlaced neo-Gothic over the neoclassical would not fully occur until after 1834 and the postfire rebuild of the Houses of Parliament in London, but medieval building stylistics were known to English architects and travelers on the Grand Tour.

Plenty of money and power must have changed hands inside this office. Tayloe was wealthy, a landed farmer, an iron merchant, and a member of the House of Burgesses. And here the building still is, nestled between his Dutch-gable house and his standard-gable colonial kitchen. The three buildings line up like an illustration of roof types from an architecture handbook. His extraordinary office existed to make Tayloe look good, a sophisticated man of refined taste, not afraid of pushing the boat out into deeper cultural waters.

So what was going on—culturally and architecturally—along Nicholson Street in 1755? It was not an attempt to recapture the imagined purity of a medieval past. It would take the excesses of the industrial revolution to bring that off. More likely, Tayloe’s office is an example of a folly, a small building put up mainly for aesthetic and self-regarding reasons rather than for shelter, safety, or work.

The word "Folly" is deeply associated with Virginia’s Eastern Shore, especially with two large estates along Folly Creek, which leads from the Atlantic to the market town of Accomac. Legends explain the names of two eighteenth-century plantations there, Bowman’s Folly and The Folly. The Bowman’s Folly tale involves an unheeded warning not to build unwisely on dodgy ground. At The Folly, the name is said to derive from a hill with a copse of trees on top, a striking feature of the original land patent as seen from shipboard. Such a natural eye-catcher, a clump of trees on high, was called a folly in Britain. Folly Creek probably got its name because of the two Folly plantations on its banks.

The estates have a full complement of early outbuildings: kitchen, smokehouse, privy, and dovecote. The Folly also has a brick icehouse. The dovecote’s details set the circa-1800 building above the normal standard for cotes. The one-story board-and-batten dovecote is octagonal with a ball finial on its segmented rooftop, and has diapered bargeboards to frustrate hawks from easily swooping down on the doves at rest on the flight platforms. It is so well designed and appointed that it is much more than dovecote. It’s a temple in honor of birds. And a folly.

Follies begin as playthings of the educated and wealthy. They are unnecessary and often whimsical buildings, based on Roman or Greek models. In Italy especially, we see them still: lots of temples, many copies of small classical shrines in honor of particular gods and goddesses; or faux archaeological ruins, raising concerns about unforgiving Time; or elaborate bridges, garden walls, and memorials, on which classical bucrania—ox skulls—and floral and leafy swags were carved in limestone. Oddest of all were the grottoes—baroque assemblages of shells and curious rocks often built cave-like into the sides of hills, pushing architectural imagination into the realm of fantasy.

When the folly craze achieves its apex of popularity in Britain in the eighteenth century, garden follies seem to be cast like bread crumbs throughout the landscapes designed by such architects as William Kent, Capability Brown, and Humphry Repton. By the start of the nineteenth century, nearly every architecture style had been employed to improve the grounds of the great country estates. There are Chinese pagodas and medieval castles, towers and triumphal gates, pyramids and obelisks, deer shelters and stray columns on hilltops serving as eye-catchers, situated where they could be seen and admired from afar.

Folly buildings are often useful. That is, they are outbuildings that contribute to the life and produce of their country house or plantation. Yet they are meant to be seen as something profound and historic: a castle, a temple, a charming though elite cottage or dairy. In 1783, Louis XVI built a rustic retreat near Versailles; it had an elaborate dairy so the queen and the ladies of the court could pretend to be couturier milkmaids, milking their cows into gilded buckets.

On a lesser scale, but in the same category, in 1812, a graceful but massive dairy or springhouse was designed by neoclassical architect Benjamin Henry Latrobe and erected on a Baltimore plantation owned by Senator Robert Goodloe Harper, who had married into the influential Maryland family of Charles Carroll of Carrollton. This was a folly dairy masquerading as a Greek temple, with a grand pedimented front and four gleaming ionic columns. It was also large enough to be a refreshing assembly room in summer—and well in excess of the ordinary needs of a dairy. The constant flow of underground water coursing through its troughs would have cooled humans as well as the cheese and butter.

You wonder if Senator Harper ever asked himself, “Why build only a springhouse when you can also get an ionic temple into the bargain?” This was a structure erected to make its owner appear serious and philosophical. And good. Still, such follies amount to little more than reputation and disposable income transubstantiated into wood and brick and stone. In 1932, the folly was moved to the grounds of the Baltimore Museum of Art to save it from demolition.

Although the word "Folly" is related to fool and foolish, its meaning can be a bit contradictory, suggesting a stupid act, from the Latin stultitia, or something pleasing and delightful, from the French folie. In 1228, Herbert de Burgh’s castle had to be torn down because the border between England and Wales suddenly shifted. This thrilled his jealous neighbors, who noted that Hubert had originally called his place “Hubert’s Folly,” or Stultitiam Huberti. But that’s merely how the contemporary Latin account seems to translate his words. More likely, the Norman Hubert used the French folie, meaning his “favorite house.” There are houses in France called La Folie.

Another early sense of folly is any building so recklessly expensive it would bankrupt its builder. In 1580, for instance, Edward de Vere bought a London house called Fisher’s Folly, a townhouse so costly it had ruined Alderman Jasper Fisher. In 1588, His Grace, Edward de Vere, the seventeenth Earl of Oxford, was himself forced to abandon this economically haunted house. In 1771, in Annapolis, Maryland, the expensive and unfinished house once intended for Governor Sir Thomas Bladen was satirized as:

Old Bladen’s place, once so famed, And now too well “the Folly” named, Her roof all tottering to decay, Her walls a-mouldering away.

Costly extravagance always indicates a streak of foolishness in builders or owners.

Eye-catchers on heights—towers, obelisks, columns, even clumps of trees—are generally considered follies. Perhaps the most remarkable is the Broadway Tower, built in 1799 on a thousand-foot Cotswold ridge on the edge of Worcestershire, England. Fifty-five feet tall, it was designed by architect James Wyatt, an early fan of neo-Gothic elements in architecture. His design here is a hexagonal tower with three turrets on three alternating sides. Too tall and ungainly to be either authentically medieval or defensively competent, it has an undeniably antiquarian feel, with robust turrets, crenelated parapets, and whimsical gargoyles. It’s also got a lower stage that angles out slightly to defend against undermining or explosives, just as a great many medieval castles, gate houses, and city walls did. Although Wyatt called his style here Saxon, the tower also has large round-headed Georgian windows with balconies—similar to the balcony on the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg, from which Governor Botetourt might have addressed Virginians forty years before the Broadway Tower was completed.

Nor are the follies expensive whimsies meant to entertain visitors to country houses. In London, there’s a folly that is the vestry of St. Pancras New Church, designed by William and Henry William Inwood and built between 1819 and 1821. In thoroughgoing Greek Revival fashion, the church looks like a six-columned Attic temple, but with a Christian octagonal tower up above.

On the east end of the church is a rectangular vestry or sacristy. From the outside, this protruding room is meant to look like the Porch of the Caryatids attached to the Erechtheum, the small temple on the Acropolis in Athens built between 421 and 406 BC. Caryatids were robed maiden figures that functioned like columns, supporting the roof. There they are today, overlooking the traffic on the Euston Road, four powerful women doing the heavy lifting. When the poet Shelley said the “We are all Greeks,” he could have had this Greek porch, and this Greek Revival church, in mind.

Other follies were built as crumbling ancient castles or chapels, like Shakespeare’s “bare ruined choirs.” These formerly proud towers, now forlorn and empty, were meant to remind viewers of the fragile nature of life and the sublime thump of Time. The quest to stare at and take on board such moments was important in eighteenth-century intellectual life. Some country squires went so far as to hire an ornamental hermit to dress up in rags, live among the ruins in their landscape gardens, and hurl imprecations—in Homeric Greek—at the promenading aristocrats.

By contrast, at his house called The Chantry in Gloucestershire, Edward Jenner, the pioneer of smallpox vaccine, made a folly of a vernacular assortment of stone, brick, and the rough and knotted barks of huge trees, all under a thatch roof. It could be just another ruined folly. In 1796, in this building, Jenner inoculated his gardener’s son and the poor of his village. For far from being a whimsical folly, a plaything of the well-heeled, the building was known as the Temple of Vaccinia.

What’s plain about three centuries of follies is the image of an elite few making small buildings mainly for the love of architecture. Others were, I think, improving the view, adorning wild nature by the human ability to build beautifully. Still others were displaying their taste and connoisseurship as well as their money, which seldom comes with instructions. For most follies, there was a usefulness beyond being expensive. All of them promoted thinking. As Thomas Gray wrote in 1751:

The boast of heraldry, the pomp of pow’r, And all that beauty, all that wealth e’er gave, Awaits alike th’ inevitable hour: The paths of glory lead but to the grave.

A well-made poem suggests more than it says. Sometimes a building can do that too. Which is why follies once had so much cultural heft. They still do.

Michael Olmert teaches English at the University of Maryland. He wrote Kitchens, Smokehouses, and Privies (Cornell, 2009) and contributed to the winter 2013 journal “On the Sublime.”