A Surveyor for the King

by Ron Bailey

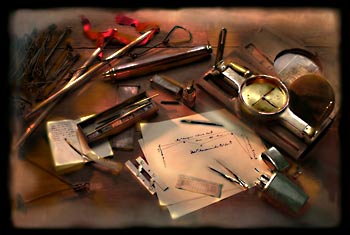

A study in the tools of

applied mathematics:

the instruments of the colonial surveyor's kit included items

ranging from iron measuring chains to steel-tipped pens

to the brass-bound compass.

In 1746, on a slope of the Blue Ridge, a man carved his initials into a tree. Tokens neither of vandalism nor sentiment, they marked the beginning of a boundary. The whittler was Colonel Peter Jefferson, a gentleman, landowner, county official, and land surveyor for His Majesty King George II. He stood more than six feet tall, and his son, Thomas, later recalled that he had the strength of three men-an advantage for a man of his position.

Colonel Jefferson often had to run survey lines straight through obstacles. It meant clambering over rocks, crawling through brush, and wading through icy streams. Another surveyor, Thomas Lewis, described working with him: "It was with the greatest Difficulty we Could get along-the mountains being prodigiously full of fallen Timber & Ivey as thick as it could grow, so interwoven that horse or man Could hardly force his way through it. . . ."

Peter Jefferson had been born thirty-eight years before at Osborne's, below Richmond, Virginia, a scion of established Tidewater stock. As a young man-improved largely by self-education-he moved west to the Piedmont and Goochland County, newly created and named for Governor William Gooch. There he spent ten years acquiring and developing property along the James River. Among his near neighbors was the county surveyor, William Mayo.

Before coming to the Old Dominion at age forty, Mayo had surveyed the West Indian island of Barbados, to the acclaim of settlers and the government. In 1728, he was selected to help survey the line between Virginia and North Carolina.

For his Goochland County duties, Mayo needed an assistant and Peter Jefferson, suited to the work, got the job. In Virginia, there was no formal course of study to become a surveyor. Young men could read such books as John Gibson's Treatise on Surveying or John Love's GEODESIA, but hands-on practice was essential. Peter Jefferson learned his profession on the job.

The fundamental job of a surveyor was to transfer land from the crown to private ownership. The process started with a settler's selection of a tract. The county surveyor recorded it in an entry book, and commonly sold the applicant treasury rights at the rate of five shillings for every fifty acres. These rights had to be submitted to the secretary of state's office in Williamsburg.

The secretary of state issued a warrant for the amount of land to which the claimant was entitled. The warrant was given to the county surveyor, who would, in time, survey the tract. Once the fieldwork was completed, the surveyor drew a plat and wrote a description of the property.

The survey plat and description were copied and entered into the county survey book, and the originals were sent to the secretary of state. Upon entry of the warrant, survey plat, and description, the secretary issued a land patent signed by the governor and marked with the colony's seal.

As an assistant county surveyor, Peter Jefferson not only surveyed tracts for other claimants, but also acquired landholdings himself. In 1734 and 1735 he patented about 1,000 acres in Goochland County, including the land on which his son would build Monticello.

Using a compass, a surveyor guides two chainmen on a scramble through the brush of a hillside, a challenge much like what they would have experienced on the colonial Virginia frontier.

In 1739, Jefferson wed Jane Randolph, a cousin of his close friend, William Randolph, and began construction of a house on a tract along the Rivanna River, a tributary of the James and the main highway of commerce from the village of Charlottesville. Jefferson named the place Shadwell, after the parish in London where Jane had been born. His surveyor's income enabled him to build a comfortable wood frame home with barns and outbuildings. In that home, Peter and Jane Jefferson's third child, and first son, Thomas, was born.

By then, more settlers were moving into the western sections of Goochland, and in 1744 the House of Burgesses, meeting in Williamsburg, passed an act dividing it into two counties, the new one to be called Albemarle, after another governor William Anne Keppel, the second earl of Albermarle. Peter Jefferson became an Albemarle County justice of the peace and judge of the court of chancery. The county surveyor position went to Joshua Fry. Jefferson became his assistant, and, when Fry was elected county militia lieutenant, Peter became the lieutenant colonel. Thereafter he was addressed as "Colonel."

Within a few months of these events, the Jeffersons moved back to Goochland County to live at Tuckahoe plantation. Its owner, and his friend, William Randolph, a widower, had died, leaving three orphans. Colonel Jefferson assumed responsibility for the care and rearing of the young Randolphs, while he pursued his surveying.

Part of the colony, the Northern Neck between the Potomac and Rappahannock rivers, was a proprietorship, where the land claim laws differed. In the seventeenth century, King Charles II had granted the peninsula to several of his supporters. Thomas, Lord Fairfax, took it over in the eighteenth century, and it became known as the Fairfax Tract. Its lands were disposed of, not by the colonial government in Williamsburg, as elsewhere in Virginia, but by the proprietor, Lord Fairfax. He appointed the county surveyors within the Fairfax Tract, and lands were surveyed and sold upon his order.

The problem of knowing where a tract of land was situated created problems. The Fairfax Tract, for instance, was to begin at the headwaters of the Rappahannock River. At the time Charles II made the grant, the position of the headwaters was not known. Lord Fairfax claimed that the headwater of the Rappahannock was the Rapidan River, and that all of the lands within the forks of the Rappahannock were part of the Fairfax Tract.

A commission was formed to resolve the question of the boundary line between the crown lands and the Fairfax Tract. Joshua Fry was appointed to represent the interests of the king. Fry, in turn, recommended that his associate, Peter Jefferson, serve as one of the two surveyors for the crown. The other was Robert Brooke. Captain Benjamin Winslow and Thomas Lewis were appointed surveyors for Lord Fairfax.

The basic instrument used by colonial surveyors was the plane surveying compass or "circumferentor," as it was commonly called in England. This was a circular brass or wooden box, housing a magnetized needle set on a bearing. The needle swiveled to magnetic north, and around it was a dial commonly graduated into 360 degrees.

The face of the instrument was engraved with a compass rose showing the letters of the four cardinal points set at the points of 90-degree quadrants. The letters for east and west were often reversed, making it easier to read the orientation of a line directly from the compass. The needle, dial, and face were protected by glass held in place by a brass ring or by glazier's putty.

The compass was mounted on a base, which extended into two arms set opposite each other. At each end of the arms were sighting vanes. Each vane was cut into a large sighting oval and a narrow slit. The oval was on top of the slit on one vane, and the slit was over the oval on the other vane. Often a thin wire or horsehair was stretched over the oval, providing more precision. The surveyor sighted the compass by peering through the slit in one of the vanes and lining up the horsehair or wire in the oval of the other vane with a target or object in the field.

Colonial Williamsburg's Willie Balderson, portraying the surveyor, and Brian Simpers, serving as his tally man, determine the bearing of a survey line with a wooden plane surveying compass.

Although surveyors used a plane surveying compass to determine the bearing of a survey line, distances were measured using a chain. Carrying the chain and measuring the distances along the survey lines was done by laborers, called chainmen.

A full surveyor's chain consisted of one hundred equal links and was sixty-six feet long. Each link represented a decimal of the chain, and twenty-five links equaled an English statutory pole. The standard chain equaled four poles. Eighty chains equaled one mile.

Although the full chain was standard equipment in England, dragging a sixty-six-foot chain through the brush of colonial Virginia's forests was impractical. A long chain would hang on brush or logs and the dense vegetation often made it difficult for the chain carriers to see each other. Colonial surveyors like Peter Jefferson used a half-or two-pole-chain, which had fifty links and was thirty-three feet.

To measure distances, the lead chainman walked toward the mark that the surveyor had determined with his compass. The rear chainman played out the chain, keeping the rear end of the chain over the beginning point. At the end of the chain, the lead chainman stopped and stuck in the ground an iron or wooden pin about twelve inches long.

As soon as the lead chainman set the pin, the rear chainman moved to that spot, and the process began again. As he advanced along the survey line, the rear chainman picked up the pin that the lead chainman had left. Chainmen carried ten pins, and when all ten pins had been collected, the chainmen knew that they had measured five full chains if they were using a half chain, or ten full chains with a full chain.

Much of the country through which the Fairfax Line passed was densely wooded and mountainous. In his journal of the expedition, Lewis described the hardships of running a straight line through heavy brush and across boulder-strewn hillsides. On one mountain slope the surveyors were so "often in the outmoust Danger this tirable place was Calld Purgatory."

At another location, the surveyors had to cross a stream, which Lewis called the "River Styx" because of its dismal appearance. The far bank was so steep that the packhorses slipped and many fell, along with the baggage on their backs, into the river. Lewis wrote: "We got all our Bagage over as it Began to grow Dark So we were Obliged to Encamp on the Bank & in Such a place where we Could not find a plain Big enough for one man to Lye on. No fire wood Except green or Roten Spruce pine no place for our horses to feed."

Often their equipment broke and had to be repaired. Some days food ran low and on others they found no water to drink. After four weeks of trial and tribulation, Peter Jefferson and company reached the Potomac. Because of a compass error, they had come out south of the spring that was the headwater of the Potomac. This meant that they had to run the line a second time, in the opposite direction, to the point where they began.

Moving to the headwaters, the men drank a toast to King George and started back Thursday, October 23, 1746. The return journey was as difficult. Several men, including Peter Jefferson, became sick. Brooke fainted in the middle of a swamp, nearly drowning in the shallow, brown water.

Colonial Williamsburg

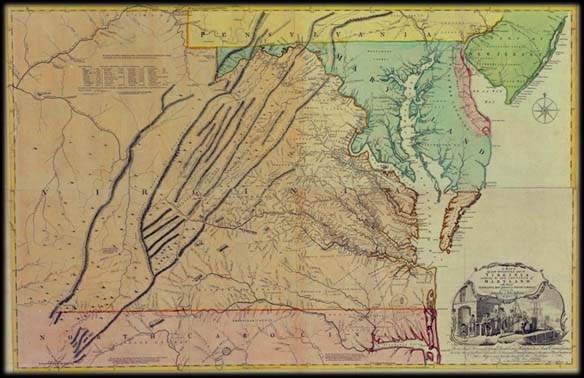

The Fry-Jefferson Map, with a cartouche depicting a prosperous colony, was the finest of colonial Virginia and often prominently displayed in the homes and offices of enterprising Virginians.

One night the surveyors became separated from their baggage party and were forced to sleep in a cold rainstorm with only handfuls of wet leaves for shelter or warmth. But all was not hardship. On October 30, 1746 the men celebrated the birthday of King George, drinking a toast to his health and firing nine guns in his honor.

Three weeks after leaving the headwater spring, the surveyors reemerged in the grove of trees on the side of the Blue Ridge where they had begun their survey, and where Jefferson had carved his initials.

The four surveyors reassembled in January at Tuckahoe. There, using paper purchased from William Parks in Williamsburg, they prepared a map of the Fairfax Line.

Joshua Fry and Peter Jefferson were selected three years later to extend the boundary between Virginia and North Carolina. As Thomas Jefferson wrote, his father "being of strong mind, sound judgement, and eager about information, . . . read much and improved himself, insomuch that he was chosen, with Joshua Fry . . . to run the boundary-line between Virginia and North Carolina."

Beginning where the 1728 survey of Mayo and others had stopped, Fry and Jefferson carried the line ninety miles into the mountains to the west.

In 1751, they collaborated on a map of Virginia. It was the first map to show the Appalachian Mountains running in the correct direction, and it became the standard cartographic reference of Virginia in the eighteenth century.

The year it was published, war broke out with France. The Jeffersons moved back to Albemarle County and Fry was appointed military commander of the provincial forces. His second in command was a young man who had been a county surveyor within the Fairfax Tract, George Washington. A few months later, Fry was thrown from his horse and killed. Washington succeeded him as commander of the Virginia Militia, and Peter Jefferson assumed the post of county surveyor for Albemarle. In 1754, Jefferson became a one-term member of the House of Burgesses.

Peter Jefferson is best remembered as the father of Thomas Jefferson. The accomplishments of the son are monuments, and the legacy of the father is far more than some initials carved into a tree on the side of the Blue Ridge. He was responsible for surveying tens of thousands of acres of frontier wilderness. He served his king and country, and, with Fry, accurately mapped Virginia.

On July 13, 1758, Peter Jefferson wrote his will. To son Thomas he left the pick of the choicest of the family's 7,500 acres. He died that August 17.

Ronald Bailey is executive director of the planning commission in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, and wrote the book Frozen in Silver, the Life and Frontier Photography of P. E. Larson, published by Ohio University Press. This is his first contribution to the Journal.