Hexagons in Williamsburg

A symbolic shape that still carries a great deal of tradition and cultural heft.

By Michael Olmert

Six is the number of creation, and perfection, symbolizing divine power, majesty, wisdom, love, mercy, and justice. -George Ferguson, Signs and Symbols in Christian Art, 1954.

The mystical number six and its perfect expression, the hexagon, long have stirred men's souls, and, in such places as Colonial Williamsburg, are still capable of making us think. We may not particularly want to consider the implications of social or personal morality with which the shape is freighted, but the architectural and structural hexagons put up in the eighteenth century persist-are great brooding sentinels, bearing messages from deep antiquity.

Not that the human figures in the eighteenth-century landscape were better than we are, not at all. It is just that they were more adept at reading the iconography of religion and virtue that once suffused the secular world. Most of us have lost that knack. Still, it is instructive to try to take on some of their cultural values and instincts, to view Williamsburg as they must have.

Perhaps no example of a hexagon in Colonial Williamsburg's Historic area is more prominent than the cupola of the Capitol at the eastern extreme of Duke of Gloucester Street.

In the matter of hexagons, there are five important versions in the Historic Area. Foremost is the bagnio, or bathhouse, in the Governor's Palace kitchen yard. Then come the three lanterns atop the Capitol, the Palace, and the Wren Building. The fifth hexagon is one that is most conspicuous by its absence-the hexagonal pulpit inside Bruton Parish Church. Though the modern one there now is square, I'm as certain as I can be the original pulpit was six-sided. Most early pulpits in England are. In Virginia, every surviving eighteenth-century pulpit is hexagonal.

That One and Two and Three which ever lives,

and ever reigns in Three and Two and One,

uncircumscribed, and circumscribing all things. . . .

-Dante Alighieri, Paradiso, 1320.

That's the thing about the number six, it is perfectible. Consider the combinations: its sum is the product of its factors-excluding itself-one times two times three. Moreover, one-sixth of it, the number one, plus one-third of it, the number two, equal one-half of it, the number three. If you resolve the numeral into six dots and pile them up, with one on top, two dots centered under that, and the final three under that, you get a triangle:

It's the divine triangle, just as Dante imagines it: the Father, followed by the Father and the Son, and finally by the Father and the Son and the Holy Spirit. It's also the triangle as a universal symbol of eternity-look at a dollar bill. Plainly, there was something mysterious and wise about the number six.

In Christian iconography, the hexagonal shape is reminiscent of a casket, a small pointed boat-like structure in which to depart this life and journey toward the New Jerusalem. It symbolizes the burial of the old sinful self. For this reason, the vast majority of pulpits, from the middle ages to the nineteenth century, have six sides. They prepare us for the voyage.

Alternatively, the hexagon's six sides represent the six days of creation, after which God rested. So the number six stands for things imperfect, corrupt, and wanting to be perfected. Again, the very shape for a pulpit.

Hence we pass thorow an Entry into another Room, where

hangs a

Pair of Scales, to weigh such as out of Curiosity would know

how much they lose in Weight while they are in the Bagnio.

-Samuel Haworth, A Description of the Duke's Bagnio, 1683.

In 1930-31, archaeologists working near the Governor's Palace uncovered the hexagonal brick foundation of a small outbuilding. It had a brick-paved floor sunken about three feet below ground level. It seemed too small and too elegant for a dairy, but just right for a small bathhouse. Bagnios, as bathhouses were often called, were prestige items, perfect for a Roman villa and thus entirely proper for the representative of a vast colonial empire to marinate in.

Documents show that the House of Burgesses allocated money for finishing "the Bannio" in 1720. And in 1779, repairs were made to this "barthing house," including installation of a new drain and a new "coating" for its "oven," suggesting that the little building had some provision for heat, an amenity of which the reconstructed building is innocent, probably because no eighteenth-century example could be found in this small size. Between 1720 and 1779, however, sloshes a great gulf of silence.

The English craze for bathhouses began in the Restoration, the London Gazette reporting in 1682 that "the Royal Bagnio is now in very good Order." And in 1695, a character in Congreve's Love for Love quips "I have a Beau in a Bagnio, Cupping for Complexion, and Sweating for a Shape."

When Dr. Samuel Haworth wrote his pamphlet on the new commercial venture called the Duke of York's Bagnio in London, quoted above, he was at pains to rehearse all the medicinal values of public spas, but he also went on to describe the building closely. Its roof had a cupola. There was an associated coffeehouse. The plunge bath itself was ten by seven feet in area, five feet deep. It held ten tuns of water. But its shape doesn't seem to be hexagonal.

Why then is the Palace bagnio hexagonal? The answer is to do with sweating. Consider the pulpit: its stock-in-trade is reform, perfectibility. What is thundered at the faithful from the pulpit is meant to make us sweat, to render away imperfection and weakness. Trying to reform sinners then was not unlike trying to slim the overweight and out-of-shape today. Similarly, the rhetoric of the bagnio pamphleteers frequently wanders over into the evangelical and even puritanical.

Behind the Governor's Palace, the original of the reconstructed bagnio was built in 1720

In A True Account of the Royal Bagnio, published in London in 1680, it's said that bagnios:

warm the whole Habit of the Body, attenuate Humors, open the Pores, move Urine, dry up all unnatural Humors, strengthen parts weakened, comfort the Nerves and all Nervous parts, cleanse the Skin, and suck out all [stale] humors from thence, open obstructions if they be not too much impacted, ease pains in the Joynts, and Muscles. By this Catalogue we see this excellent way of Sweating is a Soveraign remedy against all Diseases.

That is, the bagnio was purgatory in embryo. Six-sided, just like a pulpit, there was something improving and reforming in its character. Next time you think about the estimable governor, Lord Botetourt, consider him squeaking open the great wooden door of his hexagonal brick bagnio, and descending into a sea of smoking hot water carried thither by a grand and long parade of servants. It wouldn't be long till the end.

This Vestry has impower'd Mr. Augustine Smith

to Send to England for a Pulpit. . . .

-Vestry Book of Petsworth Parish, Gloucester County, Virginia, 1750.

Pulpits are nearly always hexagonal. And not just in Virginia. As is normal with matters of fashion and taste in Anglo-America, the notion comes from English and European examples. The massive marble pulpit in the church of Sant' Andrea in Pistoia, Italy, completed in 1301, is hexagonal and is covered with doctrinal images, most pointedly a Last Judgment. It also depicts the six Sybils, to underscore the hexagonal theme and to associate it with the Christian prophecy of eternal life. This pulpit is architecture on its way to becoming sculpture.

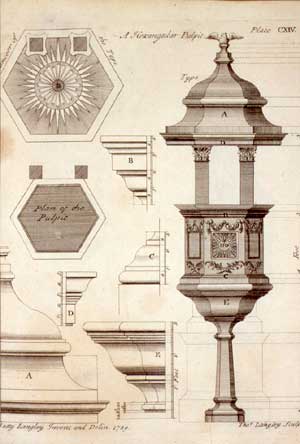

This plan for a hexagonal pulpit appeared in Batty Langley's City and Country Workmen's Treasury of Designs, published in England in 1740.

The fashion for pulpits takes off in the Middle Ages and the early Renaissance. They are placed outside the chancel or altar area, where they can focus on the people. It's not too much to say that pulpits were a proxy measure of the coming Reformation, an attempt by the church to directly instruct its flock

.After the Reformation, pulpits became even more important. Preaching was suddenly as much a focus of worship as the celebration of the Eucharist was earlier, especially in England and the Protestant north. The sermon was seen as an effective way to have the devout take on Christian doctrine, rather than have them learn by merely witnessing the mass, in a kind of ecclesiastical osmosis.

Throughout at least six hundred years of pulpit history, however, one notion is constant: the hexagon. A typical example is illustrated in Hogarth's 1762 engraving Credulity, Superstition and Fanaticism. Standing atop a "wine-glass" stem, a frequent design element in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, Hogarth's six-sided pulpit holds an evangelical minister thundering at a stunned and ape-like congregation. His harangues have cracked the soundboard over his head.

In England, more than two hundred pre-Reformation pulpits exist. The one at the church of St. James the Great, Castle Acre, Norfolk, is stunning. Its six panels have portraits of the four Latin Fathers of the Church-Saints Augustine, Gregory, Jerome, and Ambrose, all teachers and preachers. The fifth panel is blank, since it cannot be seen by the congregation; the sixth panel is a doorway into the pulpit. The superb paintings date from about 1440.

A great many impressive baroque pulpits can still be seen today in London. St. Martin-in-the-Fields, built betweeen1722 and 1724, has a mid-eighteenth-century pulpit with decorative carvings by Thomas Bridgewater. The 1733 church of St. Giles-in-the-Fields has a 1676 pulpit that survives from an earlier church on the site. St. Mary Abbots, Kensington, is a Victorian reconstruction, but its pulpit dates from 1697, a gift of King William III, who lived in nearby Kensington Palace.

The bulbous-but still six-faceted-pulpit at St. Mary-le-Strand, built between 1714 and 1724, was carved and inlaid in the eighteenth century. Standing in it, the vicar must have cut a figure not unlike a Jack-in-the-pulpit, which underscores the influence of the natural world on religious belief. Hexagons are the most efficient and stable way of filling space. Hence the honeycomb design. And the bee is itself the enemy of idleness, a symbol of Christian industry and perfectibility. Bees are acquainted with hexagons.

Plainer pulpits are associated with congregations of a more conservative or Puritan bent. In Bermuda, once a Puritan settlement, the pulpits of both St. Peter's, founded in 1612 and rebuilt 1713, and the Brackish Pond Church, which dates to 1716, are austere, undecorated cedar-but resolutely hexagonal.

The pulpit was handsomely carved black walnut; the

reading desk was below the pulpit. Mr. Empie used to read the

services below and go upstairs, while they were singing, to preach.

-Peter T. Powell, 1904.

In Williamsburg, Peter T. Powell could still recall the details of Rector Empie's services and Bruton Parish church as it was before the eighteenth-century interior was swept away. Born in 1821, he is here giving a deposition to the Reverend Doctor W. A. R. Goodwin as Goodwin researches Bruton's 1906 restoration. "In 1837," Powell said, "the high pews and the stone-paved aisles, the pulpit and the chancel remained unchanged. Before 1838 the whole had passed away."

Trouble is, Powell does not mention the shape of the pulpit. Nor do any of the other surviving accounts. We first hear of the Bruton Parish pulpit in 1703 when "a new pulpit is required" in the old brick church, the present building's predecessor. In 1715, the new church's accounts have a line entry for: "Pulpit and Canopy, £1, 10 shillings." The pulpit gets mentioned several times during the years in the vestry books, but the entries are mostly to do with its location, not whether it had six sides.

In 1939, when Colonial Williamsburg Foundation architects came to restore the pulpit they, quite rightly, chose one from Batty Langley's City and Country Builder's and Workman's Treasury of Designs, published in 1740. But rather than choose a hexagonal design, they plumped for the simple square one. It was an unusual-not to say non-conformist-design, as Langley himself must have known.

Not that square pulpits do not exist. Famously, John and Charles Wesley preached from a square portable pulpit that is now a relic displayed inside St. Giles-in-the-Fields. But the Wesleys had their differences with the Church of England.

Six: Symbolic of ambivalence and equilibrium, six

comprises the union of the

two triangles (of fire and water) and hence signifies the human soul.

-J.E. Cirlot, A Dictionary of Symbols, 1962.

On a hill overlooking the village of West Wycombe, Buckinghamshire, sits a vast hexagonal mausoleum of Tuscan limestone columns and flint infill, about ten yards to a side. The front three sides are an arcaded screen, allowing a view into a huge arena, open to the skies, for all sorts of momento mori, busts, and urns. The whole structure sits next to the village church, adjoining its cemetery.

Erected between 1763 and 1765, this may be the largest mausoleum erected in Europe since antiquity. It was built by Sir Francis Dashwood, Lord Le Despenser, born in 1708 and dead in 1781, founder of the Hell-Fire Club, which met regularly for gothic orgies of drinking and sex. Ben Franklin came to Dashwood's estate and stayed for sixteen days.

Somewhere along the line, however, Dashwood got religion, or at least he got architecture. Perhaps he wanted to make up for some aspects of his past life. In his mausoleum, he created something he hoped would stand up to fleshly temptation, something eternal, something that held out the hope of correction and resolution.

At the western extreme of Duke of Gloucester Street, the College of William and Mary's Sir Christopher Wren Building is topped with a hexagonal cupola.

The architectural historian Nikolaus Pevsner called it "a spectacular and passing strange structure of flint." But there it is today, a place where architecture meets the afterlife. And its hexagonal shape is exactly right.

The [six days of creation] is not perfect because

God

created the world in 6 days, but rather God perfected the

world in 6 days because the number was perfect.

-Vincent Foster Hopper, Medieval Number Symbolism, 1938.

In Judeo-Christian thought, the hexagon was the shape of King David's shield. It was also a double Holy Trinity, one superimposed above the other. Spatially and mathematically, it represented balance and equilibrium. People, some of them at least, were reminded of such things as they walked around Williamsburg and looked up at the lanterns above the Wren Building, where they were taught, the Capitol, where they listened, and the Palace, from which they were ruled. Pay attention, the hexagons said.

For the Greeks, it was a citizen's duty to go to plays, to exercise critical and ethical muscles. So in the neoclassical world of Williamsburg, the town fathers missed few opportunities to drive home moral points. It was good for the commonweal. In the same way that the medieval stonemasons decorated their cathedrals with didactic images, so the builders of Williamsburg sought to drive home ethics and civic responsibility. They did so subtly and in accord with traditions that were already centuries old. The six-sided messages were there for all to see. They are there still.

Michael Olmert teaches Shakespeare at the University of Maryland. He wrote about octagons in the spring 2000 issue and coffeehouses in spring 2001 magazine.