Portrait of an Artisan

An Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg Craftsman Profiled

by Harold B. Gill Jr.

Hanz Lorenz

During my forty years of research on the artisans of eighteenth-century Williamsburg, I have identified 570 gunsmiths, carpenters, brickmakers, apothecaries and the like. But I had seen the face of only one of them until last summer when a small watercolor portrait of cabinetmaker Edmund B. Dickinson turned up.

An aged sheet of reinforced paper of 51¼2-by-51¼16 inches records his likeness. He sits sideways in a chair, his arm over the crest rail, in a half-length profile that catches a long, narrow, aquiline nose. It looks to have been drawn in pencil, probably during the mid-1770s, and the color added, the specialists say, in the nineteenth century. The identity of the artist is unknown.

Dickinson’s light brown or dark blond hair is caught up in a cue at the back and curls over his ears. He wears a red waistcoat over a white shirt and neckcloth. His coat and breeches are blue. The background is a red-bordered black rectangle decorated at the corners by S-scrolls, and there is a tan margin.

Astride a Historic Area ravine, the

reconsturcted Anthony Hay Shop stands where Edmund Dickinson made

furniture before leaving to fight the British.Dave

Doody

Inscriptions on the back identify the sitter, and documents associated with the image show that it descended in a collateral branch of Dickinson’s family. In 1991, the image and the papers were presented to the Mary Ball Washington Museum in Lancaster, on Virginia’s Northern Neck. They were the gift of a distant kinswoman, Miss Althea Smart, in her name and in the name of her late brother, R. Henry Smart. Most of the papers record family efforts, based on Dickinson’s military service, to collect pensions and land grants.

Reading the book Southern Furniture, written by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Ron Hurst and Jonathan Prown, Mary Ball Washington Museum curator Cathy Currey noted references to cabinetmaker Dickinson and made the connection. Soon Phil Zea, curator of furniture, and Barbara Luck, curator of paintings, drawings, and sculpture, were in Lancaster to have a look. After appraisals, discussions, and approval by the Mary Ball Washington Museum board, Colonial Williamsburg acquired the portrait and the papers late in 2000.

Just one other likeness of an eighteenth-century Williamsburg artisan was known to exist before the identification of the watercolor of Edmund B. Dickinson. Portraits of printer John Dixon and his wife survive, but not in Colonial Williamsburg’s collections.

Attributed to the original Anthony Hay Shop on Williamsburg's north side, this card table appears in the late nineteenth-century picture below. Hans Lorenz

Williamsburg’s restored houses and shops stand as examples of the design and construction skills of its colonial-era artisans. The centuries-old structures are sources of information about the careers of the city’s craftsmen and draw of them pictures of sorts. Some craftsmen appear in the records a few times, and we have found a little about them there. For others there are artifacts but no documents—or documents but no artifacts. For instance, the business career of blacksmith James Anderson is well recorded in official records, newspapers, and account books. But no objects in the foundation’s collections can be proved to have been made at his anvil. Likewise, the tailors and shoemakers in town are known only through documents.

An open card table, stacked with books, is captured in this late nineteenth-century photo of the front hall of what is toady called the Tayloe House,a few lots west of the Anthony Hay Shop. - Colonial Williamsburg

The most numerous objects surviving from the hands of Williamsburg artisans are the copies of the Virginia Gazette and the books produced by Williamsburg printers and bookbinders. Some silver objects in Colonial Williamsburg’s possession demonstrate the skill of the city’s silversmiths and engravers. Furniture made by the hands of local cabinetmakers has been identified and acquired, too.

An elaborate Masonic chair signed by Benjamin Bucktrout has a prominent place in the foundation’s collections. Other pieces have been traced to the shops of Williamsburg cabinetmakers Peter Scott and Anthony Hay.

With all the surviving products these people made, we know something of their lives. But we didn’t know what any of them looked like.

One of Anthony Hay’s employees in 1764 was the young Edmund B. Dickinson of the portrait.We don’t know Dickinson’s age, but he was likely an apprentice at the time. Norfolk-born, he was the son of Thomas Dickinson, and it was probably Hay’s reputation as a high-class cabinetmaker that attracted Edmund to Williamsburg.

Hay provided many Virginians with fine furniture. For about twenty years, from at least as early as 1748, he worked in the shop that is now reconstructed on Nicholson Street. By late 1766, Hay seems to have contracted cancer of the face—perhaps from mahogany dust—and decided to take up tavernkeeping. In January 1767, Bucktrout announced in the Gazette that he had taken over Hay’s cabinetmaking business:

Williamsburg, Jan. 6, 1767

Mr. Anthony Hay Having lately removed to the Raleigh Tavern, the subscriber has taken his shop, where the business will be carried on in all its branches. He hopes that those Gentlemen who were Mr. Hay’s customers will favour him with their orders, which shall be executed in the best and most expeditious manner. He likewise makes all sorts of Chinese and Gothick Paling for gardens and summer houses.

N. B. Spinets and Harpsicords made and repaired.

Benjamin Bucktrout.

Hay assured the cabinetmaker shop’s customers that:

THE Gentlemen who have bespoke Work of the Subscriber may depend upon having it made in the best manner by Mr. Benjamin Bucktrout, to whom he has given up his business. I return the Gentlemen who have favoured me with their custom many thanks, and am

Their most humble servant,

Anthony Hay.

Hay purchased the Raleigh Tavern on Duke of Gloucester Street and ran it until his death in 1770. In December, his obituary appeared:

Williamsburg, Dec. 13

On the 4th instant died, of that painful and lingering disorder a cancer, Mr. Anthony Hay, master of the Raleigh tavern in this City. He underwent several severe operations, in his lip and face, for the disorder, at home; and at length went (unhappily too late) to Prince Edward, where he was some time under the care of Mrs. Woodson, famous for the cures she has made. His death is a heavy loss to his large family, to whom he was a tender husband and kind parent; and he is regretted by his acquaintances, as being a good citizen and honest man.

Dickinson likely continued to work in the shop with Bucktrout and may have had a hand in the making of the Bucktrout Masonic chair. There are two more Masonic chairs in the lodge at Fredericksburg, Virginia, that appear to have been made by Dickinson. Bucktrout operated the cabinet shop until Hay’s death when the business was put up for sale. In January, 1771, Dickinson announced that he had acquired it:

EDMUND DICKINSON, CABINET MAKER, Williamsburg, Informs the publick that he has lately opened the SHOP formerly occupied by Mr. Anthony Hay, where may be had all Sorts of CABINET WORK. Those Gentlemen who please to favour him with their Orders may depend on their Work being well and punctually executed.

Later that year he offered “good Encouragement” for journeymen cabinetmakers, and the following year James Tyrie was apprenticed to him to serve five years. The business prospered and Dickinson again needed extra hands:

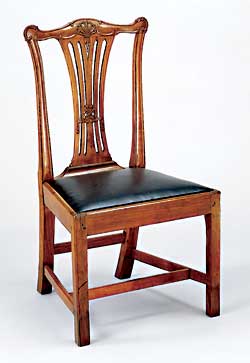

A chair thought to have been made at the cabinetmakers when Dickenson ran the shop. One of the few examples of pre-Revolution chairs made in America with neo-classical ornamentation, reproductions are displayed today at the Peyton Randolph House parlor. -Hans Lorenz

Journeymen Cabinetmakers who are well acquainted with their Business, will meet with good encouragement by applying to me in Williamsburg.

Edmund Dickinson

Dickinson provided many prominent Williamsburgers with furniture. When Governor Patrick Henry was refurnishing the Palace in 1776, Dickinson sold him pieces to the sum of £90. He performed such other services as fitting locks on chests, putting up bedsteads, gilding picture frames, and mending tables and chairs. Like other cabinetmakers, he also made coffins and arranged funerals.

This tea table came from

the Hay Shop during

the period when Dickinson worked there.

It belonged to Governor Dunmore. - Hans Lorenz

Though we know where he worked, we cannot say where he lived. He owned 250 acres of woodland “within seven miles of Petersburg” that he offered for sale in 1771, but found no buyers. On May 10, 1776, the year Dickinson became an officer in America’s new army, he advertised for the recovery of a gray horse “strayed from York Town.” In Williamsburg the following November 15, Benjamin Weldon announced that “the tenement in this city lately occupied by Capt. Edmund Dickinson” would be leased to the highest bidder.

On February 4, 1776, the Virginia Committee of Safety unanimously elected Dickinson “Captain of the recruits to be raised in the . . . District of York.” Made up of men from Williamsburg and York County, it was the 10th Company of the 1st Virginia Regiment of Foot in the Continental service.

From February to August 1776 the regiment trained in Williamsburg under Brigadier General Andrew Lewis. On August 16, the regiment marched north to join George Washington’s Grand Army in New Jersey. During the next two years, the 1st Virginia Regiment was successively part of Weedon’s, Lord Stirling’s, Mercer’s, and Muhlenburg’s brigades. On October 26, 1777, Dickinson was appointed a field officer with the rank of major. He wintered that year at Valley Forge.

On May 9, 1778, in the only document in Dickinson’s hand that survives, he wrote to his sister Lucy in Williamsburg:

Dear Girl

I embrace this opportunity to communicate a few sentiments to you as well as inform of the Joy circulating through our Camp at the Glorious news from France which I make no doubt has reached your City by this time ’tis no less than an offer of Alliance from France & Spain on the most Honourable terms possible. I make not the least doubt but it will cause a Peace before the leaves (which now are just buding out here) falls from their tinder Sprigs.

Understand by Billy Nicolson my shirts are comeing on which I thank you most kindly for have desired him to supply you with cash when you may want it as well as your Sister Agnes your provider will direct the proper use of it give my compliments to Mrs. Craig & Husband &c &c &c

When you write to your York correspondent you will present my compliments to her & Family while I subscribe myself

Your [lov]ing Brother

Edmund B. Dickinson

Camp Valley Forge

May 9th 1778

Less than two months later, Major Dickinson fought in New Jersey at the Battle of Monmouth, the last major battle of the Revolution in the North.

Sir Henry Clinton, the new British commander in America, had been forced by the threat of America’s new alliance to abandon Philadelphia. With an army of about sixteen thousand, he marched for the safety of New York. Washington, with about as many men in his command, was close on his heels, and General Horatio Gates was hurrying down from the north to engage the vanguard of the fleeing Redcoats.

General Charles Lee, who commanded five thousand of Washington’s Americans, was ordered to strike Clinton’s rear guard and hold the British while the commander in chief, three miles away, hurried forward with the rest of the Continentals to smash the English. There was the bright promise of a decisive victory. Lee, however, refused to attack, and was attacked instead. By the time Washington arrived, Lee’s corps were routed.

Dickinson's letter from Valley Forge - Tom Green

Washington checked their flight, rode straight to Lee, called him a “damned poltroon,” took command, and treated the British to a sharp fight near Monmouth Courthouse. The 1st Virginia Regiment played a crucial role by counterattacking the British right flank and relieving the pressure on General William Alexander’s wing. Driven back, the British escaped in the night.

Seventy-two American officers and men died during the battle, among them Major Dickinson. His death was reported in the English Universal Magazine. Washington believed he had lost “a valuable officer.”

Arrested, court-martialed, convicted, Lee was suspended from rank for twelve months. Ultimately, as much for affronts he offered Congress as for his conduct at Monmouth, he was dismissed from the Army.

General Charles Scott was later asked if Washington ever lost his temper. He said, “Yes, once. It was at Monmouth and on a day that would have made any man swear. Yes, sir, he swore on that day till the leaves shook on the trees, charming, delightful. Never have I enjoyed such swearing before or since. Sir, on that ever-memorable day, he swore like an angel from Heaven.”

Dickinson died a bachelor. His will left his personal property and real estate to his two unmarried sisters, Agnes and Lucy, and £20 to his sister Mrs. Judith Farrer. He left £30 to another married sister, Mrs. Elizabeth Warren, and reserved £60 out of his estate so that his nephew “Thomas Warren may be put to a good School Master or masters” if “Sister Warren will incline.”

Among the family’s papers is a poem. There is no way to know who was the author. It sounds as if it is something that could have been penned by Lucy’s “York correspondent,” the female to whom Dickinson asked his sister to present his compliments in the letter from Valley Forge. It is impossible to say. It reads:

Come my Heavnly Muse descend

Caliope to thee! I bend,

Warble forth in sweetest Lays

And sacred Truth my Edmunds praise,

Sing the greatness of his soul

His Native goodness Sense & Worth

Shew in short throughout the whole

All that’s good & grand on Earth,

Dearest favorite of my heart

May we meet no more to part,

But United fondly prove

Purest Joys of Constant Love

There is a note at the end: “This I wrote 6 months ago, for Gods sake take care of it, & let not a creature see it.”

It may be that Lucy inherited Dickinson’s portrait. Later the

wife of Robert Gibbons, she could have passed it to their daughter Louisa,

the wife of William Smart. Their son William Robert Smart, born in 1827,

would have gotten it next and passed it to his son Edmund Dickinson

Smart, born in 1869. Althea and R. Henry Smart, the Mary Ball Washington

Museum donors, were his children.

On the back of the portrait are brown ink inscriptions written in two hands, perhaps the majority of the lines by sister Lucy and the last three by William Robert Smart. They read:

Major Edmund B. Dickinson

Killed at Battle of

Monmouth

June 28th 1778

He was a brother of Lucy, the

wife of Robert Gibbons, who

was the mother of Louisa Gibbon

who married Wm Smart, who

was the father of Wm R. Smart.

Below, in the second hand, a note reads:

This picture belongs to

Edmund Dickinson Smart son of

W R Smart

Dickinson’s personal estate was appraised at a little more than £164. It included cabinetmaker’s tools, drawing instruments, a “Mason apron,” and a “New Rifle Gun.” He also owned books, among them eight volumes of the Spectator, four volumes of the Tatler, Boyers French Dictionary and Grammar, Quintessince of Poetry and Chippendale’s Designs. The “New Rifle Gun” and Chippendale’s Designs were valued at £6 apiece. The settlement of his entire estate showed it was worth more than £2,200.

To people who study Williamsburg’s eighteenth-century artisans, his portrait is almost priceless.

Williamsburg historian Harold Gill contributed “The Spanish Attempt a Jesuit Mission to the Indians of Virginia’s Chesapeake Bay” to the winter journal. He is the author of such authoritative books and monographs on Williamsburg tradesmen as The Apothecary and Artisans in Williamsburg, 1700–1800.