The Community Christmas Tree in America's Hometown

by Mary Miley Theobald

Photos by Dave Doody

Christmas in Williamsburg is officially ushered in when the beautiful community tree is illuminated on Market Square on Christmas Eve.

A small notice in the town newspaper spread the word: "When the bells begin to ring all of Williamsburg will assemble on Palace Green to sing carols and hear the exercises that have been prepared for the community Christmas tree." On Christmas night, 1915, townspeople gathered around a tall evergreen decorated with electric lights. They offered prayers, sang carols, delivered recitations, and joined in a chorus of happy exclamation as they lit their first community Christmas tree.

The idea came from Madison Square Garden in New York City, where America's first community Christmas tree had been erected three years earlier. A towering pine, the focal point of an outdoor celebration that embraced the city's diverse ethnic heritage, was hoisted into place and covered with a galaxy of twinkling electric lights.

Within a couple years, hundreds of cities and towns across the country had followed New York's example—even in New England, where Puritan forefathers had once banned Christmas outright. The appearance of a Christmas tree—that symbol of pagan ritual—in the middle of the Boston Common must have brought groans from the graves of seventeenth-century ministers who had labored so hard to eradicate every vestige of Christmas frivolity.

Virginia did not share New England's inhibitions. The Old Dominion's colonists had been celebrating the holiday season with religious services and social gatherings since the days of Jamestown. A couple of centuries later, Williamsburg had no qualms about adding the quaint German custom of the decorated evergreen to the repertoire of Christmas revelry. The city's first documented Christmas tree in Virginia was a tabletop version created in 1842 by a homesick German schoolteacher from the College of William and Mary. By the Civil War, many homes and Sunday schools decorated evergreens with candy, homemade ornaments, candles, and little gifts.

Williamsburg residents and guests gather at the Courthouse on Market Square for Christmas Eve speeches and carols before the ceremonial lighting of the community tree, a celebration dating back to 1915.

As twilight fades into night, a torch-bearing Fife and Drum Corps contingent parades down Williamsburg's Palace Green, leading guests toward the Courthouse of 1770 to celebrate the lighting of the community Christmas tree.

Williamsburg moved date and tree in 1916, choosing to have the lighting ceremony on Christmas Eve—where it remains—and putting the evergreen at the west end of the Duke of Gloucester Street, closer to the electricity source at William and Mary. The singing may have been a little unsteady that first year; the second year, the newspaper printed the words to all verses of five popular carols and suggested readers bring the page with them. The outdoor tree idea spread to Toano, a "thriving little village" west of Williamsburg, which went Williamsburg one better by inviting Santa Claus to its ceremony to distribute gifts to the children.

The invention of electric lights had made possible outdoor community Christmas trees. Early Christmas trees, whether tabletop or floor-to-ceiling, had always included lights. Most often, thin candles called tapers were wired to the tips of the branches, held more or less upright by a counterbalancing weight. Imaginative folks might make their own lights using walnut shells, egg shells, or pressed glass cups to hold a few drops of oil and a tiny wick. Those who could afford store-bought lighting might hang from the branches an assortment of tiny tin lanterns with candles inside, or miniature oil lamps with little glass globes. One tree set up at a New York church in 1859 was lit by nearly two hundred gas jets.

Safety concerns fueled the search for alternatives. The big break came with Thomas Edison's invention of the electric light bulb in 1879. Electricity brought its own risks—especially in the early years when it was a do-it-yourself effort—but it was far less dangerous than open flame. Within three years, the first electric Christmas tree lights appeared.

Credit for the invention generally goes to Edward Johnson, an Edison colleague and vice president of his electric company. At his home on New York's Fifth Avenue, Johnson stunned his neighbors with an electrified, rotating Christmas tree that blinked patriotic colors.

An invitation from 1948. After quiet Christmases during the war, people started returning to Williamsburg for the holiday.

It was brilliantly lighted with many colored globes about as large as an English walnut and was turning some six times a minute on a little pine box. There were 80 lights in all encased in these dainty glass eggs, and about equally divided between white, red, and blue. As the tree turned, the colors alternated, all the lamps going out and being relit at every revolution. The rest was a continuous twinkling of dancing colors, red, white, blue, white, red, blue—all evening.

By the 1890s, electric tree lights were all the rage among the well-to-do, who, after all, were the only people likely to have electrified homes and the money to spend on such innovation.

"No Danger! From the Lights on Christmas Trees when Edison Miniature Lamps are used," said an advertisement in Scientific American at the turn of the century. "No smoke, Smell or Grease. Miniature lamps in any color." Promotions said, "Lamps can be either bought or rented at a low cost," but in truth, they were expensive. So was the electricity needed to light them. A 1903 ad priced one string of lights at $12, an average week's wages for a working man or the equivalent of $250 today. Four years later, Sears Roebuck offered some for $4.67, or about $90 today—far cheaper but still beyond the reach of most American families. Nonetheless, Edison's Miniature Lamps sold briskly to people who wanted to enjoy their tree without having to hover beside it with a bucket of water.

Williamsburg's 1915 community Christmas tree brought a modern way of celebrating the ancient holiday to the 2,500 inhabitants of the city, few of whom owned electric tree lights.

Two years later, America was at war in Europe and the community Christmas tree seems to have become a casualty. The most notable holiday feature during the war years was the quiet. "The small boy was forced to do without his firecrackers and there was no din of horns," noted the newspaper in 1918, "much to the gratification of the old and nervous. The war has brought to some people a genuine blessing, but it is hard on the youngsters who love a noisy Christmas." There was ban on Christmas fireworks that lasted into the 1920s, and the community Christmas tree celebration lapsed altogether.

A

cresset filled with burning fatwood warms the hands of Fifers and Drummers

on a chill Christmas Eve.

Click image to enlarge

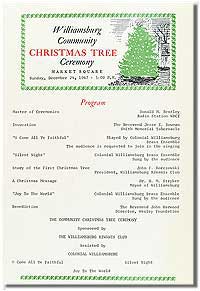

A program from nearly forty years ago mingles the religious, secular, and historical participants of a Williamsburg Christmas tree ceremony.

In 1933, Williamsburg revived the custom after "many years' suspension." The Rockefeller restoration was under way, and the town was full of excitement and civic pride. The tree ceremony was arranged by the Williamsburg Civic League, an umbrella group of civic and religious organizations, and it invited ministers and choral groups from Toano, Yorktown, and Norge. Several hundred people attended. At sundown, the tree in front of what was called the old debtor's prison—a small brick building across the street from the Courthouse—was decorated with lights by the Civic League and brilliantly lit by Virginia Electric and Power Company. Church choirs led the familiar carols, then the singers divided into groups and walked the streets of Williamsburg singing to hospital patients and shut-ins.

The following year, William and Mary initiated its own old-fashioned Christmas program December 20, before students went home for the holidays. In "a revival of ancient customs" that were never really observed there, the college's new president, John Stewart Bryan, started a Yule Log ceremony that attracted about a thousand students, faculty, and townspeople in its first year. It was, reported the newspaper, "the most successful Xmas party at William and Mary since Colonial days." Freshmen dressed as medieval serfs carried the Yule Log to the fireplace of the Wren Building's Great Hall. In his role as the lord of the manor, a costumed President Bryan greeted guests as they arrived, presenting them with tin horns, bells, and other noisemakers. For the first time, the boxwoods in front of the college's eighteenth-century Wren Building—newly restored by Rockefeller generosity—were decorated with electric lights. Lighted candles burned in twenty-four windows of the Wren—the first time an "illumination" had occurred in twentieth-century Williamsburg. A small cross of white electric bulbs hung over the door of the building, and a star made of bulbs hung from the balcony. Carrying torches, the students sang carols as they followed costumed bearers of the boar's head around the Wren and on to the dining hall for a "sumptuous supper" and a dance.

Nineteen thirty-four was also the first year that the restored buildings of Williamsburg were open to the public. No one expected guests to come during the Christmas holidays, and when they did, Restoration executives were chagrined that nothing special had been planned for them by way of decoration or celebration. The community tree caroling on Christmas Eve had been the only public celebration offered outside area church services.

The next year began Colonial Williamsburg's public Christmas programs, organized in conjunction with the community tree event. For the first time, windows at the Palace, the Capitol, the Raleigh Tavern, the Ludwell-Paradise House, Market Square Tavern, the Old Courthouse, and the Travis House were lighted by candles, as the college had done the previous year. Borrowing a custom from a local bank that traditionally lit its cupola with a lantern during the holiday season, Colonial Williamsburg put lanterns in the cupolas of the Palace and the Capitol. The Restoration took over the lighting of the community tree, the college furnished an organ to accompany the singing, the mayor addressed the crowd, and church and school choirs performed.

As more and more guests came to share Williamsburg's Christmas, the tree ceremony expanded to accommodate them. In the 1940s, pine torches and smudge pots were set about to light the town for the strolling carolers, a Christmas Day open house at the Raleigh Tavern and the Wythe House entertained hundreds with eggnog and hot wassail, and a New Year's Day bonfire and fireworks on Market Square Green ended the festival season with a bang. The Singing Candles, schoolchildren carrying lighted tapers, performed on Palace Green, and moved throughout the crowd to light other candles, which, in turn, were carried home to light the candles in the windows.

Another war brought another cessation of the celebration. Tourism during World War II all but ceased, and outdoor lighting displays were omitted at the request of the War Production Board. "Christmas will be observed quietly in Williamsburg but with many evidences of the traditional eighteenth-century customs that have been revived by the community in recent years," the newspaper said.

When the soldiers came home, guests slowly returned to Williamsburg and holiday entertainments multiplied. The community Christmas tree ceremony became more complex. In 1946 a wagon stage presented a tableau of children around the manger, and White Gifts, presents wrapped in white for overseas relief, were brought to the tree. A children's party was added in 1947 with Christmas movies, gifts, and entertainment. The permanent spruce tree that had served for years died during the war—it was replaced by a temporary tree on Market Square across from the St. George Tucker House, where Virginia's first documented Christmas tree had stood a hundred years earlier. White lights only were used on the community tree, and citizens were asked to avoid colored lights at home.

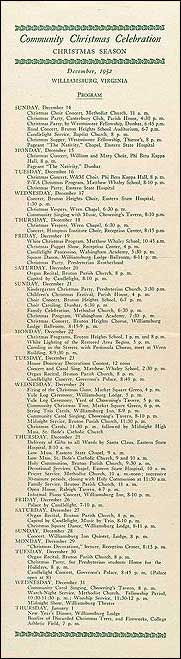

Williamsburg's popularity as a vacation destination exploded in the 1950s. Musical concerts, receptions, a Mistletoe Ball, and other activities were added to the Christmas program. Old favorites like the Yule Log and the Open House expanded to multiple locations. A puppet show, the firing of Christmas guns, and a more elaborate White Lighting of the town brought national interest. In 1952 the News-of-the-Day film crew spent five days photographing the events, producing a newsreel that reached international audiences.

By this time, the Christmas activities list took up two pages in the newspaper. As a result, the community Christmas tree lost its preeminence. Now just one activity of dozens spread over a three-week time span, the lighting no longer merited special mention in its pages.

Nevertheless, despite pauses during World Wars I and II and during the 1973 energy crisis, the custom has persisted in Williamsburg even as it fell out of favor elsewhere in America.

Each Christmas Eve the Fife and Drum Corps marches down the Duke of Gloucester, costumed interpreters fire Christmas guns, and the crowd gathers at the Courthouse steps. Men and women, boys and girls, take what warmth they can from the fatwood burning in the cressets, their candles lit, listening to the mayor's speech, bowing for a prayer, singing carols, and waiting for the moment when the switch is thrown, and the old evergreen across the street twinkles again alight.

Today, Williamsburg's annual community Christmas tree packs four centuries of holiday traditions into one sparkling Christmas present.