Dave Doody

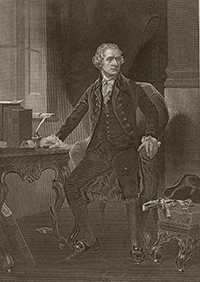

Ron Carnegie as Washington, who had to wear spectacles to read to his officers, a gesture that brought some to tears.

John Stanton

The reconstructed Temple of Virtue—now part of a New York historic site—where Washington unwound an officers’ rebellion.

The Newburgh Incident

George Washington Stops A Mutiny

by Ed Crews

In 1783, with the Revolutionary War nearly over, the American dream of an independent republic almost died at the hands of the army that fought for it. While Continental Army officers waited in camp at Newburgh, New York, for negotiators to end the conflict, their long-simmering frustration with Congress finally boiled over. Anger swept through the corps from the lieutenants to the generals. These men had had enough—enough of inedible rations, inadequate clothing and supplies, and, most important, years of foregoing pay. A coup was in the making. Even the British knew it. As one of their spies reported, military contempt for congressmen meeting in Philadelphia was so fierce that the army was “ripe for annihilating them.”

Just eighteen months earlier, in October 1781, American troops and their French allies won a great victory at Yorktown, leading to peace talks in Paris. Now, a formal treaty ending the war and recognizing American independence was expected from Europe any day. Yet, with success now tantalizingly near, the officers of army commander George Washington were flirting with mutiny. Some were eager to march on Congress in demand of their back pay. Others wanted to abandon the cause, disappear into the wilderness, and leave the bickering politicians in Philadelphia to the mercies of the British Army. Either course would bring disaster. Attack Congress and the government would collapse. Desert and the British could renew the fight and win the war. Do either and a dangerous precedent would set the military above civilian control, perhaps forever.

It was at this dangerous time that Washington decided to do something he had not done in eight years of war—address so many Continental Army leaders at one time, in one place. As he surveyed the officers before him, he saw battle-hardened veterans who had led the troops at New York, Trenton, Valley Forge, Monmouth, and Yorktown.

Still, the army’s commander was troubled as he studied his audience. The men were respectful. Military courtesy demanded nothing less. Yet, on this afternoon of March 15, 1783, an air of sullenness, skepticism, and hostility pervaded the Temple of Virtue, a rough-hewn meeting hall near his headquarters in Newburgh, New York.

For Washington, the crisis was yet another hammer blow, one of thousands endured since the war began in 1775. All took their toll. He began the war a vigorous man in his early forties. Now fifty-one, he was exhausted and, perhaps, depressed. His hair had turned gray, dental problems caused constant pain, and his eyesight was failing. In fact, he recently had ordered a pair of eyeglasses from David Rittenhouse, a Philadelphia optical expert. Before, the general was forced to borrow spectacles to read his endless paperwork.

Of the myriad problems that sapped Washington’s strength arguably the worst was Congress’s inability to pay the army. This had pushed the officer corps to the brink of rebellion. Congress was all but broke, and army pay was a low priority. Legally, Congress couldn’t tax anyone directly. Instead, funding requests went to the states, which had almost nothing. Money from loans went first to suppliers, foreign and domestic. Financial problems plagued the American cause throughout the war.

Military pay was important because, after early enthusiasm for the war waned and the militia proved unreliable, America needed a professional army with a long-term service commitment. That required financial incentives. To attract the necessary officers, Congress in 1778 offered them wartime pay plus half-pay for seven years after the war if they stayed to the end. In 1780, to stem a flood of officer resignations, Congress sweetened the deal to half-pay for life.

Complicating the pay issue was a fight between two congressional groups. Nationalists wanted a strong central government with the power to tax. Radicals wanted power, including that of taxation, to stay with the states. Nationalists’ attempts late in the war to create a 5 percent federal import tax were defeated, and odds were against the tax issue being successfully revived.

Continental officers knew all this and did not trust Congress for either back pay or postwar half-pay. They understood too that once the war ended and the army disbanded, their leverage with politicians would vanish. If demobilized without money or a firm promise of payment, some officers faced ruin. They had paid all their own costs—food, uniforms, and equipment—while on duty. Some had borrowed for their basic needs; others required cash to restart long-idled businesses and farms. Many felt cheated and fearful for the future for themselves and their families.

Washington saw trouble brewing for months. “The temper in the Army is much soured, and has become more irritable than at any period since the commencement of the war,” he wrote a congressman in December 1782. Concerned about mounting tensions, he decided against a winter furlough at Mount Vernon and stayed near the army in case trouble arose. He also worried that his men would be dismissed “without one farthing of money to carry them home.” Recently, he had revealed his concerns to his protégé and former staff officer Alexander Hamilton, now a New York congressman. “The sufferings of a complaining army, on the one hand, and the inability of Congress and tardiness of the states on the other, are the forebodings of evil,” the general wrote.

And, now in March 1783, that evil became a reality. At the army encampments surrounding Newburgh, where Washington’s command kept watch on British-held New York sixty miles away and waited for the war’s end, the officers grew restive during the bitter winter of 1782–83. Determined to get reassurances about pay, they sent a three-man committee to Philadelphia in December 1782 to plead their case and deliver a petition. It boiled with frustration. “We have borne all that men can bear,” it read. “Our property is expended—our private resources are at an end, and our friends are wearied out with incessant applications.”

On January 13, the three officers met with a congressional committee, asking for an advance on back pay and firm commitments on receiving all their regular pay plus the promised lifetime half-pay. Congress mulled the requests and directed finance superintendent Robert Morris to handle back pay. The half-pay issue, however, stirred fierce resistance. Furious, army committee chief Major Gen. Alexander McDougall wrote Washington’s loyal lieutenant Major Gen. Henry Knox that half-pay was dead and, perhaps, the army should refuse demobilization until its demands were met. Knox rejected the idea, but it had adherents.

Among them were nationalists who egged the officers on, hoping to use the army as a lever to create a federal tax and to begin building a strong federal government. Hamilton, a fervent nationalist, actually encouraged Washington in a February 13 letter to use the army to pressure Congress, but Washington knew this was a bad idea. The soldiers, he believed, were “not mere puppets,” and the army was “a dangerous instrument to play with.” An angry army easily could become a dangerous, antirepublican mob. The Continental Army already had experienced about fifty mutinies at this point. Most were caused by pay and supply issues or heavy-handed discipline. Some were little more than a few soldiers grumbling, others led to large-scale desertions, and several ended in executions. Most notably, a January 1781 revolt of New Jersey troops concluded with the shooting of ringleaders by a firing squad made up of their accomplices.

Within the army, defying the elected government had strong supporters. Among them were officers surrounding long-time Washington rival Major Gen. Horatio Gates. The historical record is fuzzy on Gates’s role in what happened next, but he was probably deeply engaged. One of his aides, Major John Armstrong, penned an anonymous letter that went to every regiment in the Continental Army on March 10. It called for defiance of Congress, a rejection of appeals to reason, a movement by the army to the frontier, and a mass meeting on the following Tuesday to air complaints. Angry at the breach of discipline, Washington banned the gathering as “irregular” and announced that a meeting would take place on March 15 to discuss the situation in Philadelphia. The senior officer present, presumably Gates, would preside. Armstrong then sent a second disjointed, shrill letter that contained more attacks on Congress and aimed to inflame passions further.

And so, with the army in turmoil, the officers gathered at noon on March 15 in the Temple of Virtue. Nobody expected Washington to appear. In his absence, hotheads probably thought that they could push the army into openly opposing Congress. As senior officer, Gates prepared to start the meeting when Washington appeared at the door, surprising those present. Confident and dignified, the commanding general strode into the room. As he did so, the officers stood and made a path for him as he moved toward the front. Washington then asked Gates’s permission to make a few remarks. With no other choice, Gates agreed.

Characteristically, the army’s commander arrived well prepared. He apologized for coming unexpectedly and asked for their patience. With that, he opened a nine-page address and began to speak. Immediately, those present realized that they’d never heard their leader talk as he did then. Normally, Washington prided himself on careful, correct, somewhat distant behavior in public. Today, however, he spoke to them man to man and, at times, with some heat.

He began emphatically: “Gentlemen, by an anonymous summons, an attempt has been made to convene you together. How inconsistent with the rules of propriety! How unmilitary! And how subversive of all order and discipline, let the good sense of the Army decide.” He attacked both letters, dismissing their author, contents, and suggestions. He argued that the officers’ welfare remained a concern of his, noting his long service with them. He rejected the call to retreat to the wilderness, saying that this would leave Congress, as well as their wives, children, and farms, defenseless. If the army took their families to the frontier, then he asked, How would they survive? Becoming more strident, he likewise spoke contemptuously of refusing to disband when peace came: “My God! What can this writer have in view, by recommending such measure? Can he be a friend to the Army? Can he be a friend to this Country? Rather is he not an insidious Foe?”

Changing tone, he told them that he expected Congress to do them “compleat Justice” and pledged to support their case. He urged caution, reason, and honorable behavior. “And, you will,” he told them, “by the dignity of your Conduct, afford occasion for Posterity to say, when speaking of the glorious example you have exhibited to Mankind, ‘had this day been wanting, the World has never seen the last stage of perfection to which human nature is capable of attaining.’ ” With those words, he finished. His speech was direct, honest, and heartfelt.

And it failed utterly.

His audience was unmoved. The men merely sat in silence. Some simmered, many were deaf to calls to reason, honor, or duty, so Washington opted for another tack. He pulled from his pocket a letter from Virginia Congressman Joseph Jones. It would show, he said, Congress’s true intent to the army. Washington began reading—then faltered. He stumbled over words, he squinted, and, finally, he fell silent. He had no choice but to use his eyeglasses.

“Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles,” he said, drawing them from a pocket, “for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in the service of my country.” The act astonished many, because few knew that his eyes were weak. Once an imposing figure, he now seemed vulnerable, tired, human. Instantly, all realized how much Washington had sacrificed for the American cause. Most men were deeply touched, and some wept openly. In seconds, with a simple, humble gesture, Washington had won over his audience. The general finished the letter, removed his glasses, and left.

The mood clearly had changed. The malcontents had lost the initiative, and Washington’s supporters seized it. Knox quickly made a motion thanking him for his remarks. Another motion passed, creating a three-man committee to frame resolutions to go to Philadelphia. Knox headed the group, which met immediately and brought several resolutions to the floor proclaiming the army’s loyalty, asking Washington to press their case, and directing Major Gen. McDougall to continue lobbying Congress. The officers adopted the measures, and the meeting adjourned.

Days later, reports of the March 15 meeting reached Congress. Among them was an emotional appeal from Washington, asking that the country meet its obligations to the officers and avoid permitting them “to grow old in poverty, wretchedness and contempt.” No doubt troubled by the officers’ fury, the legislators responded by agreeing to provide five years’ full pay in lieu of half-pay for life. The largely symbolic vote was meaningless, though, perhaps even cynical. Neither states nor Congress had funds, and none would be forthcoming. However, Congress’s action defused the situation for the time being.

While important to the army, the pay vote was overshadowed by the arrival of a preliminary peace treaty from France, which Congress lost little time reviewing. The legislature ratified the agreement April 11, declared the war over, and turned quickly to disbanding the army. Clearly, the military was a continuing expense and a potential threat, so Washington was told to furlough men enlisted for the war’s duration.

In fact, the army was fading away. Washington’s command had melted from about 17,000 men during the Yorktown campaign to fewer than 2,500 by mid June 1783. Further cuts eventually dropped the count to about 1,000 troops on duty at Fort Pitt, Pennsylvania, and West Point, New York. Even as the army shrank, feelings about lack of pay ran hot. In June, angry Pennsylvania troops marched to Philadelphia and threatened Congress. The legislators fled, and Washington dispatched loyal troops to quell the insurrection. The mutiny collapsed after the rebellious soldiers learned that forces were on their way to protect the legislators.

In late November, following the British evacuation, Washington marched into New York, where he took formal leave of the army. He then delivered his resignation to Congress in Annapolis and headed for Mount Vernon. For Washington and his army, the war was over. So was the pay issue. Many officers left with commutation certificates, basically IOUs. Desperate for cash, most men sold these at deep discounts to speculators, who did well when the first Congress convened under the Constitution provided for certificate redemption. Later, representatives tried several pension systems for enlisted men and officers. Unfortunately, these were fraud ridden and underwent several revisions.

While Washington, through no fault of his own, failed to get his officers paid, he performed what one biographer called his greatest service to the nation in 1783. By cutting short a mutiny, he may well have saved the country. Above all, his handling of the crisis reaffirmed the bedrock American principle that civilian control of the military is critical to the freedom and safety of the republic.

Ed Crews contributed “Sometimes ‘Death Was Better than the Prisoner’s Fate,’” a story on POWs during the Revolution, to the winter 2014 issue.