Online Extras

Extra Images

Yale University

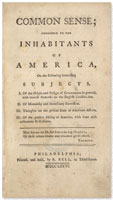

Common sense to patriots, uncommon rebellion to loyalists, Thomas Paine's pamphlet made the case for independence.

Library of Congress

A vue d'optique of Philadelphia-in which a reverse image of the title was projected by a zograscope- the city where Common Sense was printed in 1776. It was the first of twenty-five editions of the pamphlet that appeared within the year.

Dave Doody

Brian Murray, center, reads Common Sense to, from left, Jayson Knowlton, Brian Murray, Alan Ramsey, and Alex Morse.

Library of Congress

In James Gillray's satire, Paine, a corset maker's son wearing the red cap of the French Revolution, puts the squeeze on Britannia's stays, inflicting "Pain" on the British body politic.

Library of Congress

Issac Cruikshank presents Thomas Paine for sale: "Wha wants me?" Scottish vernacular for "Who wants me?" Trampling on discarded traditions, he retails radicalism and revolution.

Common Sense Arguments for American Independence

Thomas Paine Promoted Revolution, Rights, and Reason

by Susan Berg

A pamphlet published at Philadelphia in January 1776 accomplished what bloody encounters at Lexington, Concord, and Bunker Hill had not. It persuaded a critical mass of Americans to a break with England. Forty-six pages long, it was Common Sense, an instant best-seller, and a catalyst for colonists less interested in reconciliation with the mother country and more attracted to the idea of independence.

Common Sense sold out rapidly. A second, expanded edition came off the press a month later, and within a year, twenty-five more appeared. Estimates of the number of copies purchased range from 50,000 to 120,000. That’s up to 5 percent of the mostly literate white population. By a modern formula, total readership runs about 2.5 times the copies sold.

First attributed to an anonymous author, it came from the pen of Thomas Paine. It caused a sensation in England. In France, though the royal government suppressed sections critical of monarchy, it fed sentiments for a revolution that would erupt in 1789.

The printer translated and published the booklet for Pennsylvania’s German settlements. Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette printed sections of Common Sense on February 10, 1776, a month after Philadelphia set it in type. Copies circulated among Old Dominion gentry. Loyalists began to publish rebuttals, Philadelphian James Chalmers’s Plain Truth, among them. If they contested Paine’s arguments, they did not create a narrative that engaged rebel passions, and the result generated more publicity for Paine’s work.

George Washington wrote to a friend a few weeks after publication predicting Paine’s “sound doctrine and unanswerable reasoning” would persuade most colonists of the “propriety of separation.” A few months later, he wrote to the same friend to report that he judged by letters from Virginia that Paine’s pamphlet was “working a powerful change in the Minds of Men.”

How did the son of a corset maker, a transplanted Englishman in North America only a year, help shift public opinion? What were the circumstances of the man and the times that fostered his success? Are there counterparts today to Paine and his tract?

He was born January 29, 1737 in Thetford, Norfolk, and educated at its grammar school before apprenticing to learn his father’s trade, later becoming a privateer, an excise officer, a schoolteacher, a tobacco shop proprietor, and a civic activist. In 1772, Paine published his first political article, a tract supporting better pay and working conditions for excise officers. In 1774, bankrupted by his tobacco business, he traveled to London, where he met Benjamin Franklin, who encouraged him to immigrate to North America, and gave Paine a letter of introduction.

Arriving in Philadelphia in early 1775, he found work as contributing editor of the Pennsylvania Magazine, a North American version of the Gentleman’s Magazine, which appeared in London in 1731 and continued for almost two hundred years.

By the 1770s, North American colonists were reading not just for religious instruction, practical knowledge, or scholarly pursuits but for general education. Eighteenth-century magazines were a storehouse—hence the noun “magazine”—of information on developments in science, literature, and the fine arts, as well as politics. Magazines, newspapers, and pamphlets became vehicles for distributing ideas.

Paine published Pennsylvania Magazine articles on such topics as more lenient divorce laws—he and his second wife had divorced—the humane treatment of animals, and the abolition of slavery.

By 1776, Americans were accustomed to reading about political controversies. Starting in 1759, the Williamsburg, Virginia, printing office began selling pamphlets about the Two Penny Act, a law that reduced the salary of the clergy of the colony’s established Anglican Church. The debate over the statute generated six booklets. In 1766, Williamsburg printer Joseph Royle issued gentleman Richard Bland’s critique of the Stamp Act. Protestations of British taxation appeared in the Virginia Gazette during that period, and in 1774, publishers in Williamsburg and Philadelphia got out Thomas Jefferson’s A Summary View of the Rights of British America, which articulated arguments against British authority in the colonies.

The Boston Gazette published John Adams’s essay A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law in 1765, and the next year the press in Virginia and Philadelphia offered Francis Dickinson’s Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania. Widely read, the essays protested against the Stamp Act and the Townshend Duties. Adams, Dickinson, and Jefferson cited “the rights of Englishmen” as a foundation for their arguments against the actions of England’s government. Despite their complaints, they considered themselves loyal British subjects and favored reconciliation. Because of such publications and armed clashes with Redcoats, Paine had a receptive audience in early 1776.

He wrote in a style accessible to all colonists, not just the gentry. Paine used simple, clear language and short, powerful sentences. His introduction asked his readers to reexamine their views, saying, “A long habit of not thinking a thing wrong, gives it the superficial appearance of being right.”

He did not include classical allusions in Common Sense, an long-standing literary convention best understood by readers familiar with ancient Greece or Rome, which the common folk would have perceived as elitist. Paine chose the Bible to support his assertions, a book all of his readers, even those of meager education, would know. He designed his writing style so that it could be read aloud at taverns and coffeehouses, reaching an audience beyond the single-copy sales.

Though his arguments were familiar, Paine’s message contrasted with other printed protests. He created a vision of a nation founded on principles that empowered ordinary citizens, a radical idea for the time. The notion of enfranchising women, slaves, or Native Americans lay in the future, but Paine described how republican democracy would work for now, proposing a structure that gave the ruling power to the people of North America and not to Parliament. There were no references to the privileged classes who long had controlled politics. Advocating revolution, he addressed the fears the colonists had of such an undertaking by saying the present was the best time to break free of the mother country; Britain would be stronger militarily as time passed, and success harder to achieve.

Writing that “the period of debate is closed,” he reasoned that the Battles of Lexington and Concord in April 1775 between the Massachusetts militia and British soldiers, where the Revolution’s first blood was shed, changed every- thing. Citing King George III’s rejection of the Continental Congress’s appeal to resolve the conflict, the Olive Branch Petition, he wrote: “Arms, as a last resource, must decide the contest.” Paine invoked a cause in support of representative government that was greater than the conflict between England and the colonies, and said, “’Tis not the concern of a day, a year, or an age; posterity are virtually involved in the contest.”

Paine’s arguments were compelling, in part,because he was the ideal messenger. A recent immigrant, he represented no colony or section and was not promoting the interests of New England, the Middle Colonies, or the southern regions over the others. He wrote, “The cause of America is, in great measure, the cause of all mankind.” Colonists endorsed his accusations of British oppression, and responded to his call to action. He portrayed it as a global conflict, and that decided the indecisive.

Four months after Common Sense’s publication, Virginia’s General Assembly, sitting in Williamsburg, ordered that its delegates to the Second Continental Congress propose independence. Two months later, July 2, 1776, the motion carried.

During the difficult early days of the American Revolution, Continental soldiers were outnumbered, unpaid, and suffering from cold and hunger. Paine, who became an assistant to General Nathaniel Greene, began to write a series of essays titled The American Crisis. Produced under the byline “Common Sense” and read aloud to the soldiers, they contain his most memorable phrases: “These are the times that try men’s souls,” and “The summer soldier and sunshine patriot will, in this crisis, shrink from the service of his country; but he that stands it now, deserves the thanks of man and woman.” Paine’s words provided comfort and resolution to dispirited troops.

In 1777, Congress appointed Paine secretary of its Committee on Foreign Affairs. Within a year, the committee expelled him for publicizing an unfolding scandal between the United States and France. Four years later, Congress appointed him to a mission to France that secured money and supplies for the Revolution.

You remember the aphorism “The pen is mightier than the sword.” The nub of it is that words are more effective than violence, an idea as ancient as it is ambiguous. In the New Testament’s “Letter to the Hebrews” appears the claim: “Indeed, the word of God is living and effective, sharper than any two-edged sword, penetrating even between soul and spirit, joints and marrow, and able to discern reflections and thoughts of the heart.” In the words of the Prophet Muhammad, “The ink of the scholar is holier than the blood of the martyr.” Or, as England’s George Whetstone put it in 1582, “The dashe of a Pen, is more greeuous then the counterbuse of a Launce.” In 1839, Whetstone’s countryman Edward Bulwer-Lytton, the first Baron Lytton, coined the fragment of a verse we recite today:

Beneath the rule of men entirely great, The pen is mightier than the sword.There is in all a central sentiment, linking reason and force. In any culture, the power of words to persuade, to reveal, to inspire, to wound, to heal, to do good or do ill, is indeed double-edged. In the hands of a polemicist, the pen may render ideas into weapons, carve philosophies into parties, make blood sport of politics, and persuade peaceful men to mayhem and violence. Whether that it is moral or wicked may depend upon the direction in which the pen is pointed. At the outset of the American Revolution, the compositions of the Philadelphia wordsmith made him a hero of the armed struggle for liberty, but a turncoat to Great Britain—until the nation the fellow helped to create turned on him three decades later, writing him off as an apostate for promoting what he regarded as the cause of reason.

After the revolution, Paine developed a smokeless candle, worked on a steam engine, and designed the first single-span iron bridge. In 1787, he returned to England to raise money to construct the bridge, which rose over the Wear River in Sunderland in the 1790s.

In 1791, he wrote The Rights of Man, a response to Irish statesman Edmund Burke’s attack on the French Revolution. Paine said the primary purposes of government are to safeguard its people and to protect their inherent rights. His belief in democratic principles, a republican form of government, and social welfare was a natural extension of eighteenth-century Enlightenment philosophy. Fearing controversy, Paine’s first publisher withdrew his offer to sell the book. Paine found a second, and fled to France before The Rights of Man reached the booksellers. It was a sensation. A British court convicted Paine in absentia of seditious libel. The book’s immediate effect was to restore support for the French cause in England and America. One hundred years later, the American novelist Herman Melville wrote Billy Budd, the tragedy of a sailor seized from a merchantman by the British Navy. He named Budd’s ship the Rights of Man to symbolize what was lost when the crown took the seaman.

In France, Paine opposed the Reign of Terror and Louis XVI’s execution. The French imprisoned him for criticizing the Jacobins, an extreme political group that had seized control from the moderate Girondists.

During his confinement, he wrote The Age of Reason, a protest against organized religion and the power of the church. Paine was a deist and acknowledged the existence of a supreme being, but he believed organized religions promoted false representations of God and used their power to control the faithful and amass profit. He said Christianity was “too absurd for belief, too impossible to convince, and too inconsistent for practice.” Paine said much of the Bible, the book upon which some of his Common Sense arguments relied, was ludicrous. He had written another international best-seller.

Reaction to his attack on religion was sharp, and the book created enemies for Paine in the United States. He returned to America in 1809 and found the Revolution’s leaders, now statesmen in power, were wary of what they perceived as Paine’s increasing radicalism. They considered him a political liability. For that and other reasons, Paine’s longtime friend Thomas Jefferson broke off their relationship.

Paine’s death in New York in that year went little noticed. An Englishman transported his remains back to England. Rumors regarding their disposition circulated for decades—the bones were lost en route to England, Paine’s skull had been sold at auction. Their whereabouts are unknown.

Individuals in other countries have approached Paine’s rhetorical powers but not always in the interests of democracy. Karl Marx’s writings have been credited with inspiring the Russian Revolution in 1917, which overthrew a despotic government but replaced it with a Communist regime criticized for ignoring individual rights.

In a manner similar to Paine’s, twentieth-century United States presidents have used memorable words to shape a public response to contemporary issues, and to promote republican democracy. During the depths of the Great Depression in 1933, when economic conditions prompted some Americans to join radical political groups, Franklin Delano Roosevelt used his inaugural speech to comfort all citizens. He assured them that “the only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” and commenced his fireside chats, radio broadcasts designed to keep up the American people’s spirits. John F. Kennedy, in his 1961 inaugural speech, appealed to his fellow Americans: “Ask not what your country can do for you; ask what you can do for your country.” He helped launch the Peace Corps, a national program that sent thousands of young Americans to spend two years working in developing countries to raise the standard of living.

Accepting his party’s nomination for president, Ronald Reagan borrowed a phrase from Paine: “We have it in our power to begin the world over again.” Reagan disavowed the pessimism of the times and offered a vision of an America where the best days were still ahead.

Presidents and politicians of all stripes have quoted Paine to support their causes. In 1776, Paine was one voice behind whose message colonists united to revolt against England. Today, on television, talk radio, and the Internet, there are conflicting opinions clamoring to be heard. Americans can find their preferred views and values reflected by broadcasters, commentators, and opinion makers who agree with them. The nation became a home for polemicists. One wonders what Thomas Paine would make of it.

Susan Berg, former director of Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, contributed to the summer 2013 journal an article on Virginia’s first native-son historian, William Stith. For this story, she is grateful to the library’s Public Services and Special Collections staff for research assistance.