Richman, Poorman, Beggarman, Thief:

Down but Not Out in Colonial Virginia

by Martha W. McCartney

Seventeenth-century writers often described Virginia as a land of boundless opportunity, but for many colonists, life was hard. For the sick, the disabled, or people simply down on their luck, it was doubly tough. In the early years, the mortality rate was high, and hapless immigrants succumbed to disease, starvation, or violent death.

A Virginia vagabond, portrayed by interpreter Willie Balderson, accepts a cup of kindness from Tenant House residents James and lucy Atherton, interpreted by John J. Templin and Valli Anne Trusler.

--Dave Doody

Virginia's first colonists often opened their homes to the less fortunate, and conditions in the early colony forestalled some of the usual hardships of life. For example, few people reached old age. Because women were in short supply, widows rarely stayed long single. Orphans were valued for their labor and any property they inherited.

Sometimes the orphans were exploited; churchwarden Richard Kingsmill of Jamestown, guardian of the Reverend Richard Buck's retarded son, Benomi, was accused of enriching himself at his young ward's expense. An opportunistic clergyman from the lower side of the James River reportedly had designs upon Benomi's twelve-year-old sister, or at least upon her inheritance. One orphan, mistreated by his guardian, deprived of food, and clad in rags, ran away repeatedly. Neighbors finally intervened on the boy's behalf.

Forced by empty bellies to take food where they found it, vagabonds sometimes turned rogues and chicken thiefs, as demonstrated by interpreter Balderson. Virginia's legislature allowed counties to bind out such people as appretices.

--Dave Doody

In any case, the churchgoing colonists knew that "the poor shall never cease out of the land," and that charity required the authorities to ease the burdens of those less fortunate. By 1643, Virginia's assembly decided to grant tax relief to longtime residents unable to work "by reason of sicknes, lamenes or age," if local church officials agreed. Even the poor, however, had to pay parish levies.

In 1646 Virginia's burgesses, like their counterparts in England, decided poor children should be bound out in trades so that they could be educated. This could be done with or without the parents' consent. The burgesses authorized each of Virginia's county courts to send two poor or orphaned children to Jamestown to live and work in houses built for the manufacture of cloth. There, the youngsters, who had to be at least seven or eight years old, were to be taught to make cloth of flax. Child labor was commonplace; in England, philosopher John Locke recommended putting poor three year olds to work to encourage them to mature into productive members of society. Many agreed.

In 1662 parish vestries were assigned the task of providing for the indigent in general. In accord with English tradition, those too old or too sick to work were taken into the homes of friends or family, who were compensated from parish levies. A look at vestry books suggests most people on the dole wre disabled.

Vestries usually saw to it that the able-bodied poor were bound out as servants or apprentices. People of African descent increasingly were relegated to what amounted to de facto slavery. The enslaved, like indentured servants who became ill or infirm, were their master's responsibility and weren't supposed to be turned out to fend for themselves. Some undoubtedly were.

By 1668 an alarming number of people were in need of public assistance. Virginia's burgesses, perhaps drawing upon the rationale of English economists, empowered but did not require, county justices and parish vestries to build workhouses in which poor or orphaned youngsters could be schooled in useful trades "for the encrease of artificers." As far as we know, however, church officials continued to provide for the poor by farming them out to parishioners. It was a humane but financially burdensome solution to the problem.

As time passed and indentures expired, so the number of landless freemen grew, folks with little capital and no credit. A steadily expanding labor market absorbed some, and others became tenants or sharecroppers, swapping their labor for a place to live. The daring ventured into the wilderness, established small homesteads, and eked out an existence despite the dangers of the frontier.

But many landless people, mostly young males, simply wandered about the colony. Such vagabonds eluded the tax collector, depriving the colony of revenue; some were deranged or had criminal inclinations. Many were beyond the reach of the law. As the seventeenth century drew to a close, three Tidewater counties asked the House of Burgesses to enact legislation that would "punish Vagrant, Vagabond, and Idle Persons."

The population increased, economic conditions fluctuated, and the problems of caring for the poor became more vexing. In 1723 the Assembly authorized churchwardens to send vagrants back to their home parishes, where they could be bound out and made self-supporting. If a vagabond were "of such ill repute that no one will receive him or her into Service," then "thirty-nine lashes well laid on" could be administered for each offense of vagrancy.

In 1727 the colony's poor laws were updated. Vagabonds, or rogues, and orphaned or neglected children could be bound out as apprentices. Sick or disabled sailors, jettisoned by their ships' masters, became the legal responsibility of those who abandoned them. Lewd women who gave birth to bastard children had to pay a hefty fine or suffer a public whipping.

In May 1755, the Reverend Thomas Dawson of Bruton Parish and his churchwardens sought the House of Burgesses' permission to convert a dwelling on a parcel of parish-owned land near Capitol Landing into "a Workhouse, where the Poor might be more cheaply maintained and usefully employed." They said that "providing for the Poor of the said Parish hath always been burdensome," and that in "late Years hath much increased." The minister and his wardens attributed the "great Number of Idle persons" that "Lurk about the Town" to an influx of poor during Public Times: the courts met, and people poured in from the countryside. They said the needy often lingered afterward to become wards of Bruton Parish. Bruton's vestry not only wanted a workhouse, it asked for the right "to compel the Poor of their Parish to dwell and work in the said House" under whatever restrictions the House might impose.

Bruton Parish Church took initial responsibility for Williamsburg's poor.

--Dave Doody

The burgesses acknowledged that "the number of poor people hath of late years much increased throughout the colony" and authorized all Virginia parishes to build, purchase, or rent houses for the lodging, maintenance, and employment of the poor. They agreed that the establishment of workhouses was a suitable means of providing for such people and would prevent "great mischiefs arising from such numbers of the unemployed poor."

Neighboring but sparsely populated parishes were allowed to operate workhouses jointly, although no more than one hundred acres of land could be used as a poor farm. The children who resided in almshouses-what we would call poorhouses-were to be educated until they were old enough to be apprenticed. Adult inmates could be hired out as laborers, and churchwardens could apply their earnings toward their keep. Vestries could purchase raw materials, tools, and implements that could be used to produce marketable goods or items for poorhouse inmates' consumption. County sheriffs were responsible for rounding up beggars and transporting them to the nearest parish poorhouse, where they could be put to work for up to twenty days.

Not every county built an almshouse, but each that was raised was entrusted to the care of one or more overseers, usually a man selected by the vestry. He was supposed to assign the needy to tasks best suited to their abilities and to make the rules governing their conduct. He was allowed to inflict corporal punishment upon those who were disobedient or dissident, or who simply refused to work, and there were ample opportunities for the abuse of power. Anyone unwilling to live at the parish almshouse was deemed ineligible for other forms of public assistance unless adjudged too old or too sick to work. Thus, an almshouse was a place of last resort for vagrants and others who offended society's sensibilities.

The capital's almshouse stood in the area above, somewhat north of the city near Queen's Creek.

--Dave Doody

The 1755 act for maintaining the poor marked the colony's indigent with a social stigma, too, for all almshouse inmates were directed to wear a blue, green, or red cloth badge that identified them as wards of the parish. These badges, imprinted with the name of the parish to which the pauper belonged, were to be worn upon the right sleeve, near the shoulder, "in an open and visible manner." Anyone who neglected or refused to wear the badge could be whipped-up to five lashes-and lose his food allowance. Conversely, an imposter found wearing a poorhouse badge-for instance, a runaway servant or slave, or someone fleeing the authorities-could be punished. The act also required the vestry to keep a register of the poor, but none seems to exist, raising questions about how closely the act was followed.

Requiring paupers to wear badges was nothing new. A 1697 English law required all recipients of poor relief to display a red or blue cloth "P" upon their right shoulder. This method of social shaming, also used in eighteenth-century Maryland, separated the poor from the mainstream of society, which found them "nasty," "despicable," and "nauseous to the Beholder."

Because Bruton Parish's vestry records are fragmentary, we are left to ponder what it would have been like to live in its poorhouse. Were the men, women, and children housed there adequately fed and clothed? What were their accommodations like? Was the overseer humane, or someone with a cruel streak? Were the helpless victimized? If we had visited Williamsburg during the 1760s, 1770s, and 1780s, would we have seen people on the streets wearing badges signifying that they were inmates of the Bruton Parish poorhouse?

Records from other parishes in colonial Virginia show that some poorhouses were, in fact, workhouses. Others were almshouses that merely provided food and shelter. One parish's officials hired a teacher to instruct very young residents. The inmates of some poorhouses were obliged to manufacture cloth; others raised food crops. At least one parish vestry leased church-owned land and slaves to tenants, using that income to provide care to the poor in private homes.

Vestry records show that throughout Virginia, orphaned children and the elderly usually received custodial care from people who befriended them and that parish poorhouses mainly were for those who, as Thomas Jefferson said, "had no possessions, jobs, or friends." It is probable that many of the destitute were sick, malnourished, or otherwise infirm when they arrived at the parish poorhouse.

The Public Hospital in Williamsburg, which opened in 1773, siphoned off the seriously disturbed who posed a danger to society. Alcoholics, however, and people with chronic mental disorders who were considered harmless, were excluded.

Revolutionary War-era maps show that the Bruton Parish poorhouse, a complex of four or five buildings, was near Capitol Landing, on a hilltop overlooking Queens Creek. It stood upon a tract that Jonathan Druitt bequeathed to "the poor of the parish" in 1717, stipulating that his gift be used for the maintenance of a free school.

Bruton Parish's poorhouse apparently was a losing proposition, financially. In 1762 the vestry received the House of Burgesses' permission to sell three Williamsburg lots to "lay out the money for the benefit of the poor." It was authorized to use all income derived from the Druitt land for chariy. Three years later, the vestry won approval to sell some additional parish-owned real estate.

This satirical eighteenth-century print suggests some of the hazards of living on London's streets. Note the apparently homeless waifs sheltering beneath the barber

and dentist office window.

--Colonial Williamsburg

By 1769 Bruton Parish's vestry had decided to allow a joint stock company to use the Druitt property for what was called the Williamsburg Manufactory: a facility for cotton and linen cloth production. Some of project's investors, prominent local citizens, also served on the board of directors for the Public Hospital. Governor Norborne Berkeley, Lord Botetourt, subscribed £100 sterling toward construction of "the workhouse," raising the possibility that whatever buildings were on the Druitt property were being converted to another use.

In 1776, officials of the Williamsburg Manufacturing Society advertised for apprentices in order to make "some provision for the better maintenance of poor Children." A year later the society sought young people of African descent. John Crawford, Williamsburg Manufactory manager, announced that a hemp mill was being built and that the society would pay a fair price for cotton, wool, flax, and hemp. People also could have their own raw materials processed at the manufactory in exchange for a share of the finished product. Weavers and spinners were in demand, and those interested in working in their own homes would be furnished with flax. In 1777 a quantity of solid and striped linen, produced at the Williamsburg Manufactory, was auctioned before the Raleigh Tavern.

The poor were sometimes confined to madhouses like Williamsburg's Public Hospital. This 1763 Hogarth engraving satirized conditions in a similar institution, London's Bedlam.

Builder Humphrey Harwood undertook structural improvements at "the Factory," where he built a foundation for a cutting-machine and erected a pillar "in the mill room." In 1780, John Blair, Williamsburg Manufacturing Society chairman, announced that the group intended to disband. Four years later, however, society members were still talking about it.

By the late 1780s all references to "the Factory" and the poorhouse cease. Since both establishments were in use concurrently, it is probable that the cloth factory provided employment to the needy until its doors closed.

In 1978 when state archaeologists visited the site of the Bruton Parish poorhouse, which is owned by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, they found the remains of a brick foundation, evidence of other buildings, and a millstone. Later, the Bruton Parish Poorhouse Site was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 1986, the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's department of archaeological research, under the direction of Marley R. Brown III, conducted a preliminary archaeological survey of the tract so that subsurface cultural features could be identified and preserved. The millstone, once used at the Williamsburg Manufactory for grinding hemp, was moved to the Historic Area for display.

Dave Doody

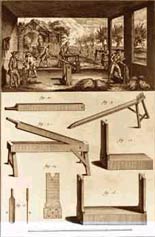

Inmates of Williamsburg's workhouse worked hemp for their keep, a process depicted at left in Diderot's encyclopedia. At right, interpreter SuCarter examines the workhouse hempstone.

The close of the American Revolution brought disestablishment of Virginia's state church, effectively ending the Anglican Church's role in public welfare. In 1780 the General Assembly created county overseers of the poor, who were authorized to see that orphans and the children of the poor were trained. Poor farms also were established to provide institutional care.

The parish poorhouse or workhouse, as a social experiment, was a failure. As an economic endeavor, it fared worse. Although poorhouses purportedly were intended "for the reformation of vagrants," where the needy could be made self-supporting, they became places where those rejected by society could be secluded. For the destitute who had no other recourse, the poorhouse may have offered a modicum of comfort. But it is likely that the poor, if given a choice, would have preferred to live almost anywhere else.

Martha W. McCartney, who wrote "Jean-Nicolas Desandrouins and His Overlooked Map of 18th-Century Williamsburg" for the December 1999/January 2000 journal, acknowledges the information contributed to this article by Andrew Edwards of Colonial Williamsburg's department of archaeological research.