Peacock Hill Architectural Report, Block 30-31 & 36Originally entitled: "Peacock Hill"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1613

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

PEACOCK HILL

In 1768 Robert Anderson's property, in what is now identified as Block 36, was referred to as being "in a retired part of the city." This pleasant description agrees with the Frenchman's Map, which shows only scattered building in the northwest corner of town above Prince George Street, and also accords with the topography. The deep ravine which originated near the present corner of Prince George and North Henry Streets effectively (as well as visually) separated this area from the more extensively developed Duke of Gloucester Street lots. The eighteenth-century buildings on Peacock Hill, to the extent that we know them from survival, documentation, and archaeology, took on the character of suburban houses on large, separated sites.

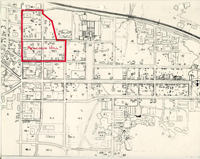

The designation of most of present Blocks 30-1, 31, 35 and 36 (see map) as Peacock Hill came about in the nineteenth century. It was used by the locals to describe a rather nice part of town in which to live. The Wolfes, who lived at Wheatland (see below) are said to have actually kept the birds. The name also separated it from the southeast corner of Block 30-1, which was in fact a separate rise called Buttermilk Hill. An elderly black woman is supposed to have 2 sold buttermilk there. The rundown condition of the Timson House on Buttermilk Hill and the well-kept appearance of the houses on Peacock Hill, both as shown in early photographs, indicates the difference in character of the two areas. Buttermilk Hill is now included in the area we are calling Peacock Hill.

The Hill was not much developed beyond its eighteenth-century appearance until the end of the nineteenth century and the beginning of the twentieth. It then became, because of its proximity and availability, a desirable place to live. Most of the houses which now remain on the Hill date from that period. What follows is an outline of the development of the area, with brief architectural notes. In order to keep things in order, the four blocks will be treated in numerical order (again, refer to map).

Block 30-1

All ten lots in this block, numbered 319-328, were deeded to Richard King, a carpenter from York County, in 1716, although lot 323 had, in 1713/14, been deeded to William Timson. Timson probably lost the lot through failure to build on it (the house which presently bears Timson's name is misidentified). King evidently built a dwelling on the property. The location of this house is not certain, but was probably 3 slightly northwest of the center of the block of lots, facing south across the ravine which cut diagonally across the block from southwest to northeast. King's will, written in 1727, directed the sale of his "houses and lots", although only six lots were left of the original ten. Hannah Shields acquired lot 322 from the Trustees in 1728; we're not sure which other three lots King gave up or sold. The King property was sold in 1737 to Henry Hacker, a planter and merchant. Shortly prior to that, however, the house had been for a short time in 1735 the residence of the portrait painter Charles Bridges, whose career in Virginia flourished under the patronage of Governor William Gooch and Commissary James Blair. Bridges had rented the house from King's estate.

Hacker died in 1742, and the dwelling, then styled "the mansion house," went to James Cocke. He held it until about 1782, when Judge Joseph Prentis became the owner. In 1782 Prentis acquired additional property, probably including the remaining four lots to complete the same block King got from the Trustees in 1716. The Frenchman's Map shows the house within a large fenced area, with one outbuilding to the north, facing the present Scotland Street.

When Judge Prentis died in 1809, the lots were sold to Henry Skipwith, along with other property in town. Prentis, prior to his death, had added a large wing to the west side 4 of his house (built by King?), and it is this additive structure which existed well into the era of photography. The house, a one-and-a-half-story, five bay frame house with exterior end chimneys, had an old wood columned porch facing south. This probably dated from the eighteenth century, and was an unusual survival. The house was called Green Hill, and is well documented in photographs.

Green Hill had a succession of owners throughout the nineteenth century, but the only changes to the property seem to have been the addition (and probably replacement) of outbuildings. It existed more or less unchanged into the twentieth century, and John Charles, whose remembrances were recorded in 1928, said that it was removed "just a few years ago." John Henderson thinks that it was demolished just prior to World War I.

With the coming of the twentieth century the appearance of Block 30-1 began to change. A row of houses, undistinguished in themselves but forming a pleasant streetscape, was built facing south across Prince George Street. Although little research has been done on the houses, they seem to date from 1900 to 1930, and were built by different owners. Most of these still exist; strictly utilitarian buildings complemented by their nearness to the Timson House, 5 the small eighteenth-century dwelling perched atop the gentle rise of Buttermilk Hill at the east end of the row.

The North Henry Street frontage was also developed during these same years. Several reasonably large houses were built, notably the two-and-a-half-story Brooks House at the corner of Scotland Street, which was erected in 1910. The Brooks House and most of the others on North Henry Street were large and commodious, and most had wide front porches, which came to be a typical feature of houses on the Hill. None of the houses pretended to any high style but were simply built and unadorned.

Shortly after World War I the number of buildings on the block was augmented by the addition of four bungalows from the wartime development at Penniman on the York River. Several of these plain, small houses were moved to Williamsburg, and a few may still exist, although the four in this block (three on North Henry Street and one on Scotland Street) have been demolished.

The east side of North Henry Street is rather blank now. Colonial Williamsburg has demolished the three bungalows and three others dating 1895-1915; all of its houses except the Brooks House, which has been thoroughly renovated and painted in bright period colors. One privately owned building, the Griffen House, breaks the view from the corner of North Henry 6 and Prince George Streets up the hill to the site of Green Hill. This house is of a quiet 1920s or early 1930s colonial revival style, two stories high and five bays wide. It was moved here from its original site within the present Historic Area.

Most of the rest of the block is vacant now. The privately owned Davis House at the northeast corner of the block facing Matthew Whaley School was also moved in from its previous site on the Palace Green. It is a two-story house with wide eaves, distinguished only by its American basic plainness and an interesting brick chimney with mousetoothed haunches. In the middle of the block to the west is the privately-owned white frame Friend House, with a Dutch gambrel roof, again in the colonial revival style, hiding behind aggressive shrubs. West of the Friend House is the Brooks Bungalow, a tiny 1950s frame cottage of the simplest type. North of the Timson House on Nassau Street is Jack Goodwin's nondescript house, sitting high and uneasy on the edge of the ravine.

It should be noted that the outline of Block 30-1 changed slightly in the development of the area around the turn of this century. The eighteenth-century line of Scotland Street was moved, probably without conscious intent, about forty feet 7 north. The Brooks House sits nearly in the middle of the original street. It's the kind of thing that drives researchers crazy.

Block 31

The early history of this block, divided into eight large lots numbered 311-318, is somewhat confused, and the available documentation doesn't always agree. Thomas Jones was deeded lots 313-318 by the Trustees in 1719/20. This deed evidently lapsed because in 1722 Christopher Jackson was deeded three of the lots and Henry Cary, overseer for the building of several of Williamsburg's public structures, was deeded the other three. Later, one of Cary's lots was again redeeded to David Minitree, an important mason. There is evidence that some of the lots were also owned by Dr. William Cocke, who was Secretary of the Colony of Virginia 1712-1720. He had also been private physician to Governor Alexander Spotswood. Dr. Cocke's wife, Elisabeth, was the sister of the important naturalist, Mark Catesby. The Cocke family seem to have lived on the property, and Mark Catesby, therefore, probably stayed here during at least a part of his sojourn in Virginia.

Prior to his death in 1720, Cocke had mortgaged the property to William Beverley, who sold it to John Pratt of 8 Gloucester County, who sold it to his niece Mrs. Elisabeth Pratt. In 1725 the property fell into the hands of Colonel Thomas Jones, who had married the widow Pratt. Part or all of the lots were bought in 1736 by James Wray, a joiner and glazier.

From surviving reference material, augmented by archaeological investigation, quite a lot is known about the house on the property. It was a reasonably large early-eighteenth-century house with leaded diamond-paned casement windows. We also know the number and names of rooms, although the exact appearance can only be guessed at. The Frenchman's Map shows extensive development about the house, which sat south of the center of the block, surrounded on the north and east by a fenced enclosure and several outbuildings. At the southwest corner of the block two large buildings are also shown, but it is not known if these were residences or outbuildings.

In 1751 Jones moved to Hanover County and advertised the house and lots for sale. It isn't certain who bought them. Joseph Prentis bought the property in 1782, and was followed by a succession of owners who seem to have done nothing constructive to the buildings on the block.

Block 31 was empty of structures by the 1860s, and stayed that way for years thereafter. It isn't known when the buildings were destroyed, or how, but John Charles said 9 that in the 1860s there were no signs at all of any houses ever standing in the block.

Redevelopment didn't begin until the very end of the nineteenth century, based on architectural evidence. The block was broken up and was in many different hands when building began after 1890. The circa 1900 Warburton House near the corner of North Henry and Scotland Street is large and rather imposing, but surprisingly simple when thoughtfully viewed. It is a tall white house, wider than most in the area, and has the ubiquitous porch across the front on the first floor. Next to it on the west is the Dovell House, much altered in the 1940s but still showing its late Victorian origin with its high, narrow facade and steep roofs. Another house which stood on the corner east of the Warburton House was of much the same type. At the west end of the block towards North Boundary Street were two other houses, now demolished, which were of a slightly later date, probably around 1915. Both two stories high, they were squarish and rather lumpy, with wide eaves and wide windows. These houses were demolished by Colonial Williamsburg as being beyond reasonable repair. This leaves a pleasant field but, as in Block 30-1, an unexpected gap in the townscape.

10In the middle of this block stands the Stryker House, a tiny Dutch colonial pastel house of the mid-1930s. This little house, and its larger and sometimes oddly matched neighbors gave the block an air of quiet gentility and permanence typical of Peacock Hill.

Facing North Henry Street only two houses remain out of the four built in a very plain late-Victorian style. The two nearest the corner of Prince George Street were torn down to make way for the present drive-in bank. The other two, the Fields House and the Shipman House, still look quite similar, although only the Shipman House is owned by Colonial Williamsburg. It has recently been renewed, and its use of exterior color is, while not original, a pleasant change from the usual white houses with green shutters. The Shipman and Fields Houses and the two now demolished were built shortly after 1900 by a local contractor named Probasco.

There were several smaller houses facing south across Prince George Street. We have no information on them, but they certainly dated after 1890, and were replaced by circa 1935 commercial development.

Around the corner on North Boundary Street the early twentieth-century feeling is still in evidence, although the large circa 1915 house at the north end of the block is no longer there to anchor the row down. Immediately north of 11 the commercial buildings on Prince George Street are two similar houses now used for commercial purposes. They are owned by the Prince George Building Corporation, and are both square and plain, two stories high, three bays wide, with low pitched kipped roofs and full-width front porches. They apparently date around 1910. Just beyond them to the north is the areas most obvious reminder of the Victorian period; a small, late-nineteenth-century confection whose gambrel roof, recessed side porch and bayed front make the viewer forget that tracery and fretwork are almost entirely absent. The charming house, with its porch roof brackets and semi-circular eaves ornament, has a slightly seductive character.

Across the alley to the north is the handsome colonial revival McGregor House. It is a two story white frame house, three bays wide, painted white, and has a nicely detailed columned porch. The house was moved to this site from its original location on the west side on the Market Square in the 1930s.

Although there are major gaps where houses are gone, the essential early-twentieth-century residential character of Block 31 is still intact except for the south edge facing Prince George Street.

Block 35

The lands belonging to the Governor's Palace included the lots in present Block 35 during most of the eighteenth century. John Holloway had been deeded lots 218 and 220-227 in 1715, but they evidently reverted to the city and seem to have had no other private owners. There was little occupation here prior to the Revolution, and the Frenchman's Map shows only one building, on the east side of the present North Henry Street near the present Clyde Hall House (see below). We don't know what the building was or what it looked like.

With the exception of Matthew Whaley School on Scotland Street, the block continues the residential character already established. West of the school is the Charlotte Brooks House, built in the 1930s. The frame house is tall and simple, two-and-a-half stories high and three bays wide. It is relieved by a delicate more-or-less Adamesque columned porch and a whimsical half-round topped dormer in the roof. The typical Peacock Hill wide porch here takes the form of a long screened porch on the east side. The house is narrow, like most on the Hill, and is much deeper than it is wide.

West of the Brooks House there were two more of the little bungalows from Penniman, but both have been destroyed. These were the only structures ever erected on this site.

13At the corner of North Henry and Scotland Streets the Farrell House still stands. It is another of the tall, steep-roofed late-nineteenth-century houses in the neighborhood, but the exterior has been altered and the typical front porch seems in this case to have been added, probably in the 1940s. Although the present appearance is later than the original construction date, the feeling of the Farrell House, enclosed with white fences and greenery probably reflects accurately the ambiance of the area at its best.

North of the Farrell House and facing North Henry Street are four more houses, all but one privately owned, which show again the mixed but homogeneous qualities of the Hill. Immediately north is the Nea House, a pleasant, small, one-and-a-half story brick house of the mid-1950s, neo-colonial in design, hiding behind its tall boxwood screen. Just beyond this is the Clyde Hall House, also owned by Mrs. Nea, possibly the oldest house on Peacock Hill (if the Timson House on Buttermilk Hill is excepted). The Hall House appears, by its decorations and round-topped attic window, to have been built about 1890.

Beyond the Hall House is the Aerni House, owned by Colonial Williamsburg. The two story, three bay, kipped roof frame house is of simple colonial revival design. The last 14 house in the row is the Fernandez House; tall, narrow, hip roofed and ugly. It was probably built circa 1920, and was moved here from its previous site behind the Geddy House on the Palace Green in 1931.

The rest of the block falls away, visually and topographically, to the corner of the Matthew Whaley schoolyard.

Block 36

Of the four blocks which constitute Peacock Hill as defined now, Block 36 is certainly more developed than the others. Only a part of it falls within the scope of this report, since the massive Chesapeake and Potomac Telephone Company building at the northwest corner of the block effectively adds to the commercial and governmental complex which has developed around the corner of North Boundary and Lafayette Streets. Since the corner where the telephone building now squats never had any residential development, however, no houses of interest were lost. It replaces a factory-like brick dry cleaning establishment.

Turn of the (twentieth) century Peacock Hill is best evoked in Block 36 in the row of privately owned structures facing south across Scotland Street. The corner lot nearest 15 Henry Street never had a house on it, and is owned by Mrs. Warburton. The next lot west held, until 1968, the fascinatingly ugly Pearl Jones House, built about 1911 (according to John Henderson) by the O'Keeffe family, among whose children was Georgia, now certainly regarded as the preeminent woman painter in the United States. The house was a large two-story, three bay structure with a two-story, two-column portico. It was built of a kind of rusticated cast concrete block made locally by Mr. O'Keeffe in anticipation of a demand for the blocks in the Peninsula building trade. This evidently didn't result, but the house stood, sour and unpleasant and later thoroughly dilapidated, until it was acquired and quickly demolished by Colonial Williamsburg. The house also had the questionable distinction of housing, for a time, a full-grown lion. The unhappy pet escaped one night in 1966, and was shot by an unsuitably large posse of local constabulary in the overgrown wilds in the center of the block.

West of the site of the O'Keeffe House still stands the two-and-a-half story, narrow, white frame Jones House, dating from the 1890s, with its steep roof and wide porch. The house hasn't changed much since it was built. West of this original house, a circa 1900 house was demolished and the cluster of modern brick Terrell apartments has been built. 16 Although their style can be described as builder colonial, the complex doesn't seriously disturb the grouping of buildings on the street.

West of the apartments another 1890s tall house, owned by Lee Elschinger, sits behind its reworked porch. Beyond this there is the pretty, circa 1935, Federal revival Raines House, with a well-detailed columned entrance porch. At the corner of North Boundary Street is the end view of another modern brick Terrell apartment building, blandly ending the residential row. Although the new buildings in the block are apartments, and the older ones have been divided up for the same purpose, the street is still residential in character.

Around the corner, facing west across North Boundary Street, there are the two one-and-a-half story frame Kelly and Rorer cottages. They have a slightly lost air, seeming to belong in an immediately pre-or post-World War II subdivision. Beyond these cottages is vacant land where another cottage stood until recently, and then land now used as a parking lot for the telephone building. Until the 1960s the local bus terminal stood here. The station, built in the early 1950s, is chiefly remembered for its bright red brick and its particularly virulent blue trim.

17Up the North Henry Street side of the block the picture is much more spotty than the order and predictability of Scotland Street. Just north of the empty lot at the corner of Scotland Street is yet another vacant lot. Unlike its neighboring space, however, this site until recently held a house of some interest. Here stood Wheatland.

The six lots in this block were numbered 212-217, and our first record of them is in 1722, when Thomas Corbin of Urbanna held them. Circa 1732 Corbin sold the lots to John Holloway, first Mayor of Williamsburg, Burgess, Speaker and Treasurer of the Colony of Virginia. Holloway married the widow Elisabeth Cocke, sister of Mark Catesby. There was considerable interaction between the Holloways and their property and the Jones family and their property discussed under Block 31.

In 1746 the lots were sold to Dr. John Amson. Amson died prior to 1765, and in the year Robert Anderson and his wife were in possession of the lots. In 1768 the house on the property was described as being "very commodious" by Mayor James Cocke in a Virginia Gazette article. The article was concerned with the outbreak of smallpox in the city and, more particularly, in the area we call Peacock Hill.

18In 1769 Doctor James Carter bought the lots, and sold them in turn to William Holt for £1143, a large sum even taking wartime inflation into account.

The Frenchman's Map shows a large house, with several outbuildings, in a very large fenced yard. The shape and design of this house are not known, however, for it was replaced in the early-nineteenth-century by a large wood house in the Federal style. This two-and-a-half story house, with its low pitched gable roof and late-nineteenth-century two-story porch on the south elevation is the one recalled by local residents and shown in the earliest available photographs. The nineteenth-century occupants of the property are mostly known, but it is not known which of them built this house, nor when it first came to be called Wheatland. Within the structure of the building were some timbers which had been re-used from an earlier building, possibly the eighteenth-century house of the same site which had been occupied by Corbin, Holloway, Amson, Carter and Holt.

The Henderson family bought Wheatland in 1907 from Judge Hensley, and continued in residence until 1968. It was acquired by Colonial Williamsburg. When the house was examined, it was determined that the main portion of the building dated circa 1820, but that a small north wing and a separate Dairy were probably of eighteenth-century date. 19 The condition and location of the house and dairy mitigated against their preservation, however, and they were demolished after the removal of much early material.

North of the site of Wheatland is the Lawson House, a circa 1902 house with a typical tall and narrow front, steep roof and wide front porch. The Lawson House has been renovated and brightly repainted by Colonial Williamsburg.

Beyond the Lawson House is an instructive example of what all of Peacock Hill might have become. The Levinson bungalow of the 1920s, unobtrusive in itself, now has an intrusive two-story motel behind it in the rear yard. Although the motel is not particularly unsightly, it is highly disruptive to the block, and by its presence and mediocre maintenance, is no help to its neighbors. Perhaps its only redeeming value is that, with other equally obvious intrusions, it was the inescapable signal that the Hill stood in need of help.

Beyond the bungalow and motel is a vacant lot where Colonial Williamsburg tore down a circa 1900 gambrel roof house found to be beyond structural salvation. Next is the square, hip-roofed Hitchens House, circa 1910. It is privately owned and somewhat down at the heels. Beyond this, 20 at the corner of Lafayette Street, is a circa 1925 one story frame bungalow on a high foundation, now owned and kept in repair by Colonial Williamsburg. West of this on Lafayette Street is another Hitchens house. This is a small and plain 1950s rental unit.

The margins of Peacock Hill, those blocks surrounding it and facing it, tell the story of what late-twentieth-century Williamsburg is in terms of its townscape. To the south there is the commercial development of Block 23, with the college dormitory at the northwest corner. All of these buildings are of brick, in a more-or-less Georgian 'style. To the southeast and east are the edges of the Historic Area. The distinction between Historic and non-historic areas is somewhat blurred by the green open spaces and white wood buildings, all of residential scale. At the northeast is Matthew Whaley School and its playing fields. To the north and northwest is the governmental and commercial development of the modern city, and on the west is the residential row along North Boundary Street, which is a visual if not an actual extension of the architectural character of the Hill.

In these edges most of the aspects of the town represent themselves, in most cases compatibly, with the still-recognizable 21 enclave of Peacock Hill. The Hill is certainly not of a single date, but it is still more or less in one piece, and that is its overriding value to us.

What must be apparent in reading this account of building types and dates is that the area saw slow and somewhat irregular development, mostly by families who had a little money to spend for a new house although rarely enough for even the simplest kind of ostentation or show. What strikes the viewer is the extreme plainness of the houses, perhaps a lasting result of economic privation remaining after the Civil War.

The area is surely matched, except perhaps in its history of occupation by artists of note, in many small southern towns. It is distinguished not so much by its architecture as by the easy co-existential quality of its development. If there is any surprise in Peacock Hill it is the fact that it is still there. Lying so close to the center of 1920s-present civic development, it would have predictably gone through the expected sequence of decay and commercialization almost inevitable in similar areas of other towns. The decay in fact began, mostly after 1945, but the peculiar circumstances of proximity to and partial acquisition by Colonial Williamsburg stabilized the trend before it became irreversible.

22Surprisingly vacant by urban standards, irregularly occupied by dwellings of some architectural interest, Peacock Hill is now stable and certainly capable of varied improvement. The treatment of this consequential area, the planning and care it receives, will continue to be pivotal to the character of twentieth-century Williamsburg.

J. F. Waite

22 February 1978