Brush-Everard House Architectural Report Part 1, Block 29 Building 10 Lot 165 & 166Originally entitled: "The Brush-Everard House (Restored) Architectural Report Block 29, Colonial Lots # 165 and # 166 Part I"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Research Report Series - 1577

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE

Block 29, Colonial Lots #165 and #166

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE

(Restored)

Block 29, Colonial Lots #165 and #166

The Brush-Everard House was restored under the direction of the Department of Architecture of Colonial Williamsburg, Inc. Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, Architects, acted as consultants. Restoration was started in May, 1949

A. Edwin Kendrew, Vice President and Resident Architect.

Division of Architecture, Construction and Maintenance

Mario E. Campioli, Director of the Department of Architecture

Ernest M. Frank, Assistant Director, Department of Architecture

Singleton P. Moorehead, Architectural Advisory Consultant

Field Notes and Measured Drawings made, November, 1937, by

John W. Henderson and Richard A. Walker

Archaeological Excavations and Archaeological Drawings and Report made by

James M. Knight Report dated December 11, 1947

Working Drawings made by John W. Henderson, Chief Draftsman

Joseph F. Jenkins

Albert M. Koch

Robert E. Taylor

Ralph E. Bowers

Working Drawings checked by Eric R. Enholm

Landscape Drawings by Alden Hopkins

Sidney I. Benton, Construction Superintendent

This report was prepared by A. Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne for the

Department of Architecture (Architectural Records.)

February 22, 1950

Revisions and additions made in February, 1952

THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE

PART I

THE EXTERIOR

CONTENTS

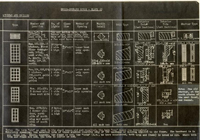

| Page | |

| I. Notable Residents of the Brush-Everard House | 1 |

| John Brush, Gunsmith | 2-4 |

| Henry Cary, II, Architect-Builder | 4, 5 |

| The Two John Blairs | 6 |

| Thomas Everard, Public Official | 6-8 |

| The Smith Family, Century-long Residents | 8-13 |

| II. Audrey, a Legendary Occupant | 14 |

| III. A House of History and Romance | 15a |

| IV. Growth of the House | 16 |

| V. The House Exterior | 25 |

| Brickwork | 25-36 |

| Stonework | 36 |

| Walls | 36-39 |

| Trim | 39-42 |

| Roof | 42-45 |

| Dormers | 45-51 |

| Entrance Stoop | 51 |

| Bulkheads | 51, 52 |

| Windows, Shutters, Trim | 53-55 |

| Basement Grilles | 53-55 |

| VI. The House Interior | 56 |

| Floors | 57, 58 |

| Brickwork | 58, 59 |

| Staircase | 59-62 |

| Mantels | 63, 64 |

| Panelling | 65-67 |

| Cornices | 67-70 |

| Corner Boards | 70, 71 |

| Doors and Trim | 72, 73 |

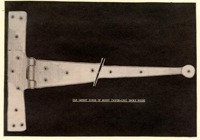

| Hardware | 74-79 |

| Painting and Color | 80-85 |

| Wallpaper | 88 |

| VII. The Brush-Everard House, an Example of Painstaking Restoration | 89 |

| VIII. Acknowledgements | 91 |

| IX. Sequence of Ownership | 92 |

| X. Dating of a Building | 97 |

| Dating of Brush-Everard House | 98 |

| XI. Bibliography | 102 |

| XII. Addendum | 101a |

| XIII. Index | 106 |

BRUSH-EVERARD

HOUSE (LEFT), OFFICE (RIGHT) AND KITCHEN (CENTER, REAR)

BRUSH-EVERARD

HOUSE (LEFT), OFFICE (RIGHT) AND KITCHEN (CENTER, REAR)

THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE

Block 29, Colonial Lots #165 and #166

The small story-and-one-half weatherboarded house that stands on the east side of the Palace Green a short distance from the Palace, itself, has in the past been variously known as the Audrey House, the Page House, the Smith House and the Brush House, and is now officially designated as the Brush-Everard House, to call to mind its first owner as well as a later one of distinction. Its favored position as a neighbor of the Governor's House implies some social or political prominence in the individual, John Brush, who first came into possession of lots #165 and #166 on which it and its outbuildings are built.

JOHN BRUSH. GUNSMITH - THE FIRST OWNER.

John Brush is said to have been brought to Virginia by Governor Spotswood. We are reasonably certain that Brush was a gunsmith, a calling which in that day was a vital one in the colony.* It is quite possible that Spotswood looked upon Brush as an individual of sufficient importance to warrant his bringing pressure to bear on the city trustees to grant him this exceptional location. At any rate John Brush, gunsmith, by virtue of a deed from the city dated July 8, 1717, became owner of two half-acres of the most desirable land in Williamsburg. The deed contained the customary provision from the Act of the Assembly of 1705 obligating him within two years to build on the lots a house 40 ft. long and 20 ft.- 2 bldgs if lot not on the main street [illegible] wide, or to return the land to the city. Brush must have complied with this regulation because he continued in possession of the lots after the stipulated time had elapsed, so that we can assume that the first house was built on lots #165 and #166 sometime between 1717 and 1719. Whether this was the dwelling which, with considerable alterations, to be sure, has survived to this day is a matter of conjecture, but the house, whatever it was, was one of the earliest built in Williamsburg.

3The evidence indicating that John Brush was a gunsmith is circumstantial but it

is nevertheless good. We know that he was keeper of the arms in the Public

Magazine. In this capacity he would doubtless have been in charge of the

gunsmith's shop located in the building and responsible for the repair and

maintenance of the firearms stored there. Brush was also employed on one

occasion to fire the guns at the Palace in celebration of the King's birthday.

It would not, of course, require a gunsmith to fire the guns, but Brush,

nevertheless, would have been a logical person to do this. The fact, on the

other hand, that Spotswood placed him in charge of what must have been one of

the feature events of a gala program tends further to support the thesis that he

was a protêgê of the Governor's. Probably the most conclusive evidence,

however, of the nature of Brush's profession, is contained in the inventory of

his personal effects compiled after his death, which occurred sometime before

December 19, 1726, the date his will was probated. Along with a few items of

furniture, mostly

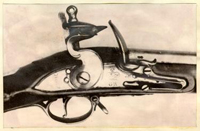

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY

GUNSMITH'S SHOP SIMILAR IN GENERAL CHARACTER TO THE SHOP WHICH JOHN BRUSH

MAINTAINED ON HIS LOT EAST OF THE PALACE GREEN

4

indifferent in quality, there is a long list of those tools and materials which

a smith would have used. Among the latter are found, furthermore, a number of

items which are specifically the equipment of a gunsmith, and some of these may,

be mentioned: "3 gun barrils, 1 stock ... 1 gun ... 2 pan borers*

... 1 tinder box and powder trier, 2 long shank bills,#

1 drawbore½..."X

EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY

GUNSMITH'S SHOP SIMILAR IN GENERAL CHARACTER TO THE SHOP WHICH JOHN BRUSH

MAINTAINED ON HIS LOT EAST OF THE PALACE GREEN

4

indifferent in quality, there is a long list of those tools and materials which

a smith would have used. Among the latter are found, furthermore, a number of

items which are specifically the equipment of a gunsmith, and some of these may,

be mentioned: "3 gun barrils, 1 stock ... 1 gun ... 2 pan borers*

... 1 tinder box and powder trier, 2 long shank bills,#

1 drawbore½..."X

FIRING

MECHANISM OF A TYPICAL MID- 18th CENTURY "BROWN BESS" MILITARY MUSKET

OF ENGLISH MANUFACTURE. THIS GUN AND OTHERS LIKE IT ARE NOW OWNED BY COLONIAL

WILLIAMSBURG, INC.

FIRING

MECHANISM OF A TYPICAL MID- 18th CENTURY "BROWN BESS" MILITARY MUSKET

OF ENGLISH MANUFACTURE. THIS GUN AND OTHERS LIKE IT ARE NOW OWNED BY COLONIAL

WILLIAMSBURG, INC.

John Brush's inventory with its meager listing of furniture, is that of a man whose life was spent in his shop and who probably devoted relatively little attention to has house. It is likely, not only that his dwelling was poorly furnished, but also that this first house itself was a modest structure. Examination of certain of the woodwork details in the existing house seems to indicate 4a that much of the enrichment of the interior is of a date later than that of the original building of the house. In other words, it was undoubtedly not John Brush, capable and respected artisan though he was, who embellished the interior and laid out the extensive pleasure garden at the rear, but some later owner who gave more thought than the gunsmith to the art of fine living.

HENRY CARY II. ARCHITECT-BUILDER

At some uncertain date not long after the death of John Brush lots #165 and #166 passed into the possession of Henry Cary II, son of Henry Cary. The Cary's, father and son, were contractors and builders ("overseers" or "undertakers") and between them constructed most of the larger public buildings erected in Williamsburg during the first three decades of the 18th century.*

5All that is definitely known about Cary's ownership of lots #165 and #166 is that the builder sold them in 1742 to William Dering, a dancing master. How he acquired the lots is not known, although it has been suggested that they passed into his hands upon his marriage to his (third) wife, Elizabeth Russell, who may possibly have been the former Elizabeth Brush, John Brushes daughter, who is believed to have owned the property.

There is no documentary evidence to prove that Cary lived inCary [illegible] until 1728. Brush was [illegible] the house but it seems reasonable to suppose that he did, since he was employed in 1720 to supervise the completion of the Palace. This was a major undertaking which must have required close and constant supervision on the part of the architect-builder. In view of this a residence near to the scene of operations would have been highly desirable, so that it appears altogether likely that, owning the former Brush house, Cary would have occupied it.

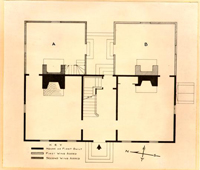

We also have reason to believe that Henry Cary III known as the "gentleman builder" of Ampthill, which formerly stood in Chesterfield County, may also have given the one-time residence of John Brush the form which it had at the highest point of its development and the form to which it is being restored. (This thesis will be discussed at some length later in the report.) If the theory is indeed fact it would explain the elaboration of the interior which we hesitated above to attribute to the inspiration of John Brush.

THE TWO JOHN BLAIRS, BELIEVED TO HAVE BEEN OWNERS OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD PROPERTY

From deeds relating to the property it seems that John Blair, the elder, possessed lots #165 and #166 after 1745. It is not known how long he held the lots but he died in 1771, and a John Blair -- his son it must have been -- transferred lot #172, the plot on which the garden was located, to Thomas Everard in 1773. To our knowledge neither the elder nor the younger Blair ever occupied the house.

THOMAS EVERARD - HIGH PUBLIC OFFICIAL AND CITIZEN OF REPUTE

Thomas Everard, whose name is linked with that of John Brush in the title of the house, acquired lot #172, the plot which adjoins lots #165 and #166 on the east and on which the pleasure garden was located, by deed from John Blair, Jr. in 1773. There is strong evidence indicating that by September, 1779 he had also come into possession of the neighboring lots mentioned above, although the exact time and manner in which he acquired them is not known.

It is quite likely that Everard not only owned but also occupied the house. We know that he lived near George Wythe, whose residence lies diagonally across the Palace Green from the Brush-Everard House, since in a letter of 1770 to John Norton & Sons, merchants in London, he says: "Your Son has been sometime confined sick at my Neighbor Mr. Wythes but is now pretty well recovered and gone to York." We also know that he lived in the vicinity of Dr. Gilmer's, for in his diary (1751) John Blair, Sr. notes that he "Spent the eveng (after a visit at Mr.Everard's) at Doctr Gilmer's ...." Dr. Gilmer's house and shop were on 7 lot #163, at the corner of Nicholson Street and Palace Green, a stone's throw from Everard's place.

Everard was clerk of Elizabeth City County from 1743 to 1745, and then clerk of York County from 1745 to 1784. He also served as clerk of the Committee of Courts of the House of Burgesses, and as Commissioner of Accounts.

Among the numerous documents bearing Everard's signature, which may still be examined at the York County Courthouse, is the will of Governor Fauquier, which he witnessed. It may be of some significance that after the Governor's death, Everard purchased items of the latter's personal property amounting in value to£125. Only a man of means could have afforded to do this, but, without much doubt, Everard was well-to-do. The official positions which he held for so many years were among the most important in the colony and these were probably lucrative as well. There is reason behind this enquiry into Thomas Everard's financial condition - if he was, in fact, so well-off it may have been he who, on lot #172 at the rear of the house, planted the still-existent boxwood arbor and built the pool which we believe to have been situated to the north of this.

It is also possible that Everard, during his occupancy of the house, did more than build the garden. In September of the year (1773) in which he acquired lot #172, and, it may be, lots #165 and #166 as well, he ordered from Norton & Sons a long list of goods. Among articles of clothing, household equipment etc., is found an order for "100 feet window glass, 11 inches by 9½." Earlier in the year he had also ordered "100 lb. white lead ground in Oyl." These orders seem to indicate that he contemplated some building or building repair work, 8 and it is possible that the materials were to be used on his house outbuildings.

We have intimated that Everard was a man of consequence in the colony and other facts bear this out. He was, for instance, a member of the Bruton Church vestry which in 1769 decided to build a new steeple (the one which still stands) and repair the church. He was appointed by the General Assembly in 1770 a member of a committee, otherwise composed of Peyton Randolph, John Randolph, Robert Carter Nicholas and John Blair, Jr., "... to agree on a Plan for the Hospital ... [for the insane -- said to be the first in America] and to advertise the building thereof ...." One of Everard's daughters married the Rev. James Horrocks, Commissary of the Bishop of London and President of the College. Martha, another daughter, became the wife of Dr. Isaac Hall, a doctor of high standing in Petersburg. Hall seems to have succeeded Everard in the ownership of lots #165 and #166, and he may have acquired them through his marriage to Martha Everard.

THE SMITHS - RESIDENTS OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE FOR NEARLY A CENTURY

Sydney Smith bought the Brush-Everard House from Daniel

P. Curtis on December 8, 1849, and from that day until the Williamsburg Holding

Corporation acquired it nearly one hundred years later, it remained in

possession of the Smith family. Some of these Smiths who lived there so long

were especially interesting people and we shall say a few words about them.

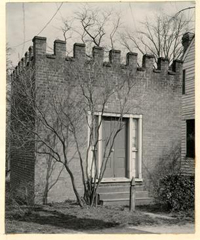

Sydney Smith, the son of Henry Smith of Yorktown, was a lawyer, having been

graduated from the law school of the College of William and Mary in 1846. He was

builder of the Gothic revival office with its crenelated

9.

walls, which until recently stood just north of the house. This he used as his

law office. Romance entered Sydney Smith's life when he walked down to the foot

of Palace Green, fetched a Miss Virginia Bucktrout from the Repiton House where

she lived to Bruton Church across the main street and wed her.

The Smiths, man and wife, were blessed with seven children -- three sons, Sydney, Henry and Alva, and four daughters, Martha, Virginia, Cora and Estelle. It is with the last two that this short history of the Smith family will henceforth concern itself, and for these reasons: they lived their long lives through in the Brush-Everard House and died there -- Miss Cora in 1939 and Miss Estelle in 1946 -- and they were, each in her way, personalities worthy of being commemorated by a brief biography.

Miss Estelle, the youngest of the children, was born at the outset of the Civil War. She was tall, and frail in body -- so frail, in fact that "she was practically transparent -- it seemed that a gust of wind might carry her away."* But her spirit -- her ardent love for life -- sustained this frail and ailing body. She was proud and autocratic, critical and outspoken but a kindly soul withal, loving and loved by her neighbors. She was a famous raconteur -- her witty tales of Virginia life -- told and retold many times, to be sure, will long be remembered.

Miss Cora was much prettier than Miss Estelle, with lovely complexion, and she was in her youth one of the belles of Williamsburg. She differed also from her sister temperamentally; she was sweeter and less caustic, but brave, intelligent and active-minded like her sister. She was the housekeeper.

Long before the Restoration was conceived the sister's

Smith were ordinary keepers, so-to-speak. To be more exact they took in roomers

and

10

MISS

CORA B. SMITH * MISS ESTELLE SMITH*

MISS

CORA B. SMITH * MISS ESTELLE SMITH*

TEA! THE MILDLY STIMULATING LEAF PLAYED A PROMINENT ROLE IN

THE LIVES Of TWO SUCH EMINENT CONVERSATIONALISTS AS MISS CORA AND MISS ESTELLE

not only fed them but fed them well with old Virginia dishes prepared by the

cook, quick-tempered but kind-hearted Josephine who, with a maid and crotchety

old Uncle Nick, the colored handy-man, presided over the ancient brick kitchen

behind the house. Their spoonbread and scalloped oysters were renowned. It was

over this board that Miss Estelle, with dignity, but with charm and wit besides,

presided, regaling her guests --

11.

college faculty members and students mostly, but tourists also -- those who even

at that early day had heard of Williamsburg -- with funny stories.

On one occasion such a guest was a Reverend Dr. Goodpasture. Miss Estelle, throughout the meal, frequently and with consistency, addressed the clergyman as "Dr. Cowpasture." When the worthy man had departed, Miss Estelle, assailed by a terrifying suspicion of the truth, turned anxiously to a friend and said: "Oh, Mary, I think I may have called him 'Cowpasture!'"

A body of legend has grown up about the lives and experiences of those estimable characters, the Smith sisters, and many stories might be related. Of these, by far the rarest is that of the Lost Lion, a tale already told in winged-worded prose and lofty verse.--

Tale of the Lost Lion*

There was once a scrawny, tired lion. He was a circus lion and awed the gaping multitude upon our Market Square. Let Mrs. George P. Coleman tell us how

"His dash for liberty he made,

He merely longed to seek the shade

Of some old garden, to forget

The circus din, his paws to wet

Once more in dew ..."

The "rompant" lion loped and jogged across the Tucker garden and up the Palace Green, scattering the terrified throng before him and drawing hardy, would-be captors in his wake. Arriving at the Smiths', he leaped the picket fence and landed on our sisters' porch, 12.

"The house shook as though steeds were driven

O'er wall and roof; a blind was riven,

As though a lightning bolt from Heaven

Had crashed its red artillery."

The sisters within, disturbed in mind, debated about the source of the unholy racket:

"Tis a lunatic, they muttered, smashing in our ancient door.

This was never done before."

Miss Estelle peered from a windows and perceiving it to be just a bigger, clumsier cats cried out:

"Sister hear that awful roar.

'Tis a lion, nothing more!"

Our lion meanwhile, embarrassed by the awkward spectacle he was making of himself there swinging on the shutter, dropped lightly to the ground and hastened around the house. Proceeding down the boxwood arbor he ran full into the arms of Uncle Nick, who in the gathering dusk failed to recognize Leo's leonine character and much provoked thrust him off with: "Git down thar, calf!"

Thereafter, liberty was brief for the fugitive. Approached by his trainers with a cage -- he meekly, perhaps even cheerfully, surrendered his freedom and entered it. He had been on the loose just long enough to realize that even for a lion, liberty means care and responsibility and that the adventurous life brings with it many a harrowing experience.

The morning after this nerve-racking event Josephine

discovered, graven in mud upon the porch, four paw prints. She was about to mop

them off when Miss Estelle restrained her. The maiden lady darted inside the

house and soon reappearing with brush and paint can, she carefully daubed the

paw prints over with enduring white lead, so that they might bear

13.

testimony to all the world of the truth of this fabulous tales which the sisters

down the years were to recount again and yet again. As Mrs. Coleman remarked on

concluding her recital of the story, it is a great pity that the Brush-Everard

porch was not an early one, so that it could have been retained, with Leo's

padded paw marks on it -- to be restored and re-restored, by the scholarly

archaeologists and architects of Colonial Williamsburg. Thus, perpetually fresh

and new, like Martin Luther's famous inkblot, these gleaming tracks had served

to mark, for generation upon generation of fascinated tourists, the spot where a

frenzied lion in his dash for freedom trod upon Miss Cora's porch and indignant

Miss Estelle's.

THE

SMITHS' OWN LION, KING OF BEASTS-REFLECTS IN CAGED SOLITUDE UPON HIS HISTORY

-MAKING-. SONNET-INSPIRING-, NEVER-TO-BE-FORGOTTEN (WE'LL NOT LET THE STORY

DIE!) EXPLOIT

THE

SMITHS' OWN LION, KING OF BEASTS-REFLECTS IN CAGED SOLITUDE UPON HIS HISTORY

-MAKING-. SONNET-INSPIRING-, NEVER-TO-BE-FORGOTTEN (WE'LL NOT LET THE STORY

DIE!) EXPLOIT

AUDREY -- ANOTHER FAMOUS RESIDENT OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE

To many Williamsburg citizens the Brush-Everard House has long been known as the "Audrey House." This came about through the fact that Mary Johnston, celebrated Virginia author of "To Have and to Hold," lays part of the action in her novel "Audrey" in a "small white house" on the Palace Green in Williamsburg. In fact she seems to locate this small white house on the site of the Brush-Everard Houses as the following passage (p.241) indicates:

Hayward walked on to the grape arbor, and found there a black girl, who pointed to an open door pertaining not to the small white house, but to the portion of the theatre which abutted upon the garden.

The theater alluded to was evidently the first theater of Williamsburg, which was located, we believes on lot #164, between the Brush-Everard and the Levingston Houses. Because of its close proximity to the Brush-Everard House, the colored girl whom Hayward encountered in the grape arbor might readily have pointed to it. Thus the Audrey House of the novel was located, apparently, where the Brush-Everard House stands, so that the two are without much doubt one and the same. Indeed, the Brush-Everard House is the only house on the Palace Green which now, or, for that matter, in 1901, when the book was written, could have answered to the designations "small white house."

The house as it is presented in the novel is an imaginary creation, based, probably, upon Miss Johnston's impressions of the Brush-Everard House* and other similar eighteenth century houses. In a letter 15. written in 1930 to Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin she said:

It has been so very many years since I wrote that old romantic novel, Audrey! At the time I read many things -- all that I could lay hands on -- about the Williamsburg of the first quarter of the eighteenth century. I tried for a certain accuracy, though of course all was idealised for fictional purposes .... My description of it [the theater] is imaginary. Nor when I described "a small white house which adjoined a larger building" (The play house) did I intend actually to pre-empt the Page house ....

There is in the novel little actual description of

Audrey's house, nor, for that matter, is it important that we have it. To us the

significant and intriguing point is that, to all intents and purposes, the house

in fiction and the house in fact are one.

THE

KITCHEN OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE BEFORE ITS RESTORATION: THE CORNER OF THE

LATE EAST ADDITION (SINCE REMOVED) IS SEEN AT THE LEFT.

THE

KITCHEN OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE BEFORE ITS RESTORATION: THE CORNER OF THE

LATE EAST ADDITION (SINCE REMOVED) IS SEEN AT THE LEFT.

A HOUSE OF HISTORY AND ROMANCE

It is not usual in Williamsburg or elsewhere, to find a house, like the Brush-Everard, of modest size and pretensions, which not only boasts significant historic associations but which also has so much romance hovering about it. Much of the action of a well-known novel (Audrey) centers about this house. Unusually interesting people have resided in it and they have left us a legacy of fascinating stories. A lion, distressed in heart and doubt-tormented was once an uninvited, unwelcome visitor. No spirit residents, its true, have cast their fearsome spell about the house -- no shade of John Brush, for example, pounding on a phantom anvil, sends a spine-chilling, hollow clang at midnight o'er the Palace Green. But the house does have its mystery, for long-departed occupants have left enigmatic marks upon its window panes and a symbol, familiar to us, but as yet not with certainty deciphered, upon a board beneath the roof.

THE MYSTERIOUS SYMBOL

The interesting and puzzling symbol and two accompanying letters -- a "B," apparently, and a second letter too indistinct to be identified -- were found on some short, rough boards, 5/8" thick (once, presumably, parts of a packing box) which were nailed to the lower ends of the roof rafters near the north end of the main building. The symbol and letters had been painted on the boards and were blackish-brown in color.

The device, which consists of the numeral,

"4," with an elongated shank or leg which terminates in a double

"X," was frequently used

15-b

THE

SYMBOL PHOTOGRAPHED WHILE STILL IN PLACE

in colonial times on packing boxes, bottles, hardware, pipes, etc. We are still

uncertain as to what it signifies and several possible interpretations have been

advanced to explain its meaning. The most reasonable of these interpretations,

according to Dr. A. Pierce Middleton, is the followings-- In medieval times the

symbol "XX" represented an alembic or still, and, placed upon some

chemical product, it signified that the product had been distilled. A figure,

"2," placed immediately above the double "X," indicated that

the liquid had been twice distilled. When a product had been distilled four

times the numeral, "4," was placed above the double "X."

Such a product of the medieval alchemists art was of the highest quality. Once

this symbol became the trade mark of quality in chemical products, it was

gradually carried over into other fields, and became the stamp of the highest quality for merchandise generally. The

elongation of the stem of the "4" is to be explained by the fact that

each manufacturer or merchant placed his initials on either side of the figure,

and the leg of the figure was elongated to facilitate this.

THE

SYMBOL PHOTOGRAPHED WHILE STILL IN PLACE

in colonial times on packing boxes, bottles, hardware, pipes, etc. We are still

uncertain as to what it signifies and several possible interpretations have been

advanced to explain its meaning. The most reasonable of these interpretations,

according to Dr. A. Pierce Middleton, is the followings-- In medieval times the

symbol "XX" represented an alembic or still, and, placed upon some

chemical product, it signified that the product had been distilled. A figure,

"2," placed immediately above the double "X," indicated that

the liquid had been twice distilled. When a product had been distilled four

times the numeral, "4," was placed above the double "X."

Such a product of the medieval alchemists art was of the highest quality. Once

this symbol became the trade mark of quality in chemical products, it was

gradually carried over into other fields, and became the stamp of the highest quality for merchandise generally. The

elongation of the stem of the "4" is to be explained by the fact that

each manufacturer or merchant placed his initials on either side of the figure,

and the leg of the figure was elongated to facilitate this.

This explanation of the meaning of the interesting mark seems plausible. In fact, Colonial Williamsburg has been confident enough in 15-c its validity to use the symbol, with the letters "C" and "W" placed at either side of the shank of the "4," as a sign of quality on all official reproductions of Williamsburg furniture and furnishings sold under the Craft Program.

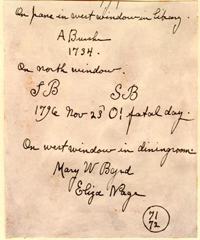

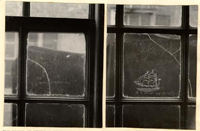

THE ETCHINGS ON THE PANES

Copies of the incised inscriptions on the Brush-Everard windows were made while they still existed by Miss Estelle Smith and presented to Colonial Williamsburg in a letter. A facsimile of this record is included here, as well as photographs of two of the window panes, made by Thomas Williams while the sash were still in place.

MISS

ESTELLE SMITH'S TRANSCRIPT OF THE WRITING ON THE WINDOW PANES

MISS

ESTELLE SMITH'S TRANSCRIPT OF THE WRITING ON THE WINDOW PANES

The "A Bushe (Brushe?)" and the date, "1734" may have been scratched on the pane of the west window of the library (northwest room)1734 - Eliz. Russell by some kinsman of John Brush. We have no information about A. Brushe,See Research Report (1956) p. 4 Anna Marie Brush & Anthony Brush however, so that our surmise must remain surmise, unless by chance we come upon some facts about him.

On a west window of the dining 15-d (southwest) room are scratched the names, "Mary W. Byrd" and "Eliza Page." It seems likely that Eliza Page was a relative of Margaret Page, the second wife of Governor John Page, who is known to have occupied the house for an indeterminate period around 1815.

As for the signature, "Mary W. Byrd," -- this may have been scratched on the window pane by any one of three persons of that name, who lived in Williamsburg or its vicinity between 1761 and the Civil War period. We would like to be able to establish it as that of Mary Willing Byrd, the beautiful and brilliant wife of Colonel William Byrd III, who owned a town house, the Allen-Byrd House, in Williamsburg, as well as Westover, but we have no way of substantiating this. On the other hand it may have been that Mary Willing Byrd who was the daughter of Addison Lewis Byrd and Susan Coke, and whose brother, Addison Lewis Byrd, died in 1856.Again, we have no proof that it wasn't the Mary W. Byrd who married Richard Coke, Jr., a member of Congress and owner of the Dr. Barraud House from 1823 to 1843. It is evident that we need more facts before we can state with certainty which Mary Byrd was the "signer."

The etching of the three-mated bark, on one of the west windows of the northwest room is interesting as an objet d'art rather than as an historic document. Considering the difficulty of the medium the exactness and not unsatisfying quality of the drawing indicate that its author, the undersigned H. B. Smith (probably Henry, the son of Sydney Smith), was not only familiar with ships, but was also something of an artist.

Though the signatures and the drawing above discussed

have a certain interest for us, it is the inscription on the north window of the

library which really fascinates us - "SB -- 1796, Nov. 23 - O! fatal

15-e TWO

PANES OF WINDOWS OF THE NORTHWEST ROOM, THE ONE ON THE LEFT BEARING THE FAMOUS

"O! FATAL DAY" INSCRIPTION.

day." This is of the stuff romance is made of. Let us not inquire too

deeply into it butt rather hope, historians though we be, that we may never find

out who SB was nor what ill luck or tragedy he met with on the day. Let's keep

this small but living flame of romance burning.

TWO

PANES OF WINDOWS OF THE NORTHWEST ROOM, THE ONE ON THE LEFT BEARING THE FAMOUS

"O! FATAL DAY" INSCRIPTION.

day." This is of the stuff romance is made of. Let us not inquire too

deeply into it butt rather hope, historians though we be, that we may never find

out who SB was nor what ill luck or tragedy he met with on the day. Let's keep

this small but living flame of romance burning.

CHANGES IN THE EXTENT OF THE HOUSE AS REVEALED BY ITS OLD FOUNDATION

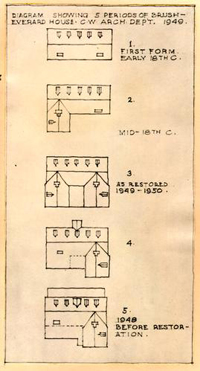

The plan arrangement of the Brush-Everard House follows the familiar pattern with broad central hallway and rooms on either side. The interior plan as seen today is, however, the result of a development, since through the years certain additions and modifications took place. In its first form there were, it is believed only two rooms and a hallway at the first floor level and two bed rooms on the second floor, reached from the stair hall. The enlargement of the dwelling by the addition of two wings toward the east was occasioned by a constantly increasing need for floor space.

The plan arrangement of she original part of the Brush-Everard House is common enough in and around Williamsburg. It differs, however, from most other local house plans in one respect, namely, in the location of the fireplace in each of these two rooms, not at the ends, as is customary, but at the rear center of the room (see Fig. 1, next page). With the fireplaces so located it was a simple matter to expand the area of the house by the addition of rooms at the back, as shown in Figs. 2 and 3, and it is quite likely that the first builder, from the outset, contemplated doing this. The original house, in that case, would have been an expansible house, which brings to mind present-day dwellings which are so designed as to permit the addition of further rooms with only minor changes to the structure. This possible intention of enlarging the house, together, of course, with the presence of the chimneys at the back, may be responsible for the fact that no dormers, so far as we know.. were ever placed on the rear roof slope.

17.The next development in the growth of the house was the addition of the south wing (Fig. 2). The findings made in 1947 in the course of excavating the site of this wing after the removal of the late shed addition which then existed leads us to some interesting conclusions concerning this wing. The archaeologist first came upon a nearly complete colonial foundation about 9" wide for a wing similar in size and position to the existing north wing. Continuing the digging, however, he located, several feet below the first foundation wall and paralleling the northern side of it for about two-thirds of its length, a second and still older colonial foundation 20" wide. This foundation was apparently built of salvaged brick fro curved coping brick, possibly from a garden wall of the Palace, were found laid up in it.

The most logical explanation of the existence of these

two levels of colonial foundation work is that the south wing existed in two

states in the eighteenth century. The 20" foundation wall, naturally,

17a.

would represent the earliest state of this wing and the 9" wall the later.

The depth of the early foundation indicates that this first version of the south

wing had a basement. In addition we believe this to have been connected with the

basement under the main house because indications of a former door opening

exists in the common foundation wall between the two. As a matter of fact, since

there is evidence in the foundation wall of the main house that a basement was

added after this portion of the house was built, it has been suggested that this

may have taken place at the time the south wing with its basement was built.

17a.

would represent the earliest state of this wing and the 9" wall the later.

The depth of the early foundation indicates that this first version of the south

wing had a basement. In addition we believe this to have been connected with the

basement under the main house because indications of a former door opening

exists in the common foundation wall between the two. As a matter of fact, since

there is evidence in the foundation wall of the main house that a basement was

added after this portion of the house was built, it has been suggested that this

may have taken place at the time the south wing with its basement was built.

The first south wing, evidently, disappeared in colonial times and a second, with 9" foundation walls, took its place. This happened, probably, at the same time the north wing was erected for the foundation walls of the two wings are similar in width and character. With the building of these two wings the house attained its greatest extent (Fig. 3).

In Fig. 4 the south wing is once more missing so that it must have burned or have been removed for one reason or another.

Fig. 5 shows the state of the house as it came down to us with a shed-roofed addition of the nineteenth century occupying part of the site of the south wing. The house, of course, was restored to the state represented by Fig. 3.

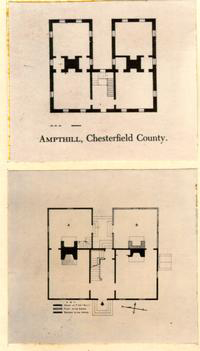

18.

FIRST

FLOOR PLAN OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE, SHOWING THE FIRST FORM OF THE BUILDING

AND ITS TWO ADDED WINGS (SEE KEY).

FIRST

FLOOR PLAN OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE, SHOWING THE FIRST FORM OF THE BUILDING

AND ITS TWO ADDED WINGS (SEE KEY).

SIMILARITY IN DEVELOPMENT AND FINAL FORM OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE AND AMPTHILL

It has not been possible for the architects or the research department to

establish the precise date when this third, complete house form came into

existence, although there is a circumstantial basis for its having been built

before 1750. There are striking points of resemblance between the Brush-Everard

House and Ampthill,* which originally stood in Chesterfield

County, and which was built by Henry Cary II, architect-builder, in the 1730's.

A fact of considerable importance in this connection is that Henry Cary II owned

the Brush-Everard House during precisely the same period. Could the building of

both the Brush-Everard House and Ampthill have been under the trained direction

and supervision of Henry Cary? Such a supposition is supported by the existence

in the houses of a number of similar features. The plans were alike in both,

even in the placing of the two fireplaces on the rear wall. Both were enlarged

by similar additions. Both had the very unusual rear court or passage. Finally,

there is a striking

(ABOVE)

PLAN OF AMPTHILL (CHESTERFIELD COUNTY) BUILT BY HENRY CARY II. (BELOW) PLAN OF

BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE, OWNED BY HENRY CARY II DURING THE 1730's WHEN AMPTHILL WAS

UNDER CONSTRUCTION.

20.

similarity in the square shape of the rooms of the two houses. These facts seem

to indicate that one individual (Henry Cary II) erected both houses.

(ABOVE)

PLAN OF AMPTHILL (CHESTERFIELD COUNTY) BUILT BY HENRY CARY II. (BELOW) PLAN OF

BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE, OWNED BY HENRY CARY II DURING THE 1730's WHEN AMPTHILL WAS

UNDER CONSTRUCTION.

20.

similarity in the square shape of the rooms of the two houses. These facts seem

to indicate that one individual (Henry Cary II) erected both houses.

THE RESTORATION OF THE HOUSE AND THE REMOVAL OF ANACHRONISTIC FEATURES IN THE COURSE OF IT

The house front remained pretty much the same

throughout its long history, although it is known to have received, at an early

date, the addition of a hooded stoop at the front door, and later on a

"Victorian" porch which faced on Palace Green. The roof dormers were

also changed at some time before 1900. All of these alterations were considered

by the Restoration architects as anachronisms and, as such, were

BRUSH-EVERARD

HOUSE IN ITS FINAL FORM, WHEN ITS RESTORATION WAS UNDER-TAKEN, 1948-1950. THE

VICTORIAN PORCH AND THE GOTHIC OFFICE BUILDING AT THE LEFT WERE REMOVED IN THE

RESTORATION PROCESS. THE CENTER DORMER WAS REPLACED BY ONE SIMILIAR TO THE

ORIGINAL ONES THAT ADJOINED IT.

21.

removed. The purpose prompting the Restoration has been to recover the

eighteenth century appearance of the house. To achieve this, long continued

effort was exerted to gather together all of the known facts about the house,

and a thorough study of its structure was made to bring to light the changes

that the house fabric underwent. With this information at hand the architects

were able not only to reestablish the house as a whole in its first form, but

also to restore the exterior and interior with convincing precision to their

original condition and appearance.

BRUSH-EVERARD

HOUSE IN ITS FINAL FORM, WHEN ITS RESTORATION WAS UNDER-TAKEN, 1948-1950. THE

VICTORIAN PORCH AND THE GOTHIC OFFICE BUILDING AT THE LEFT WERE REMOVED IN THE

RESTORATION PROCESS. THE CENTER DORMER WAS REPLACED BY ONE SIMILIAR TO THE

ORIGINAL ONES THAT ADJOINED IT.

21.

removed. The purpose prompting the Restoration has been to recover the

eighteenth century appearance of the house. To achieve this, long continued

effort was exerted to gather together all of the known facts about the house,

and a thorough study of its structure was made to bring to light the changes

that the house fabric underwent. With this information at hand the architects

were able not only to reestablish the house as a whole in its first form, but

also to restore the exterior and interior with convincing precision to their

original condition and appearance.

As we have observed, there were several successive plan arrangements, each becoming increasingly more spacious. The house growth, so far as ground floor area is concerned, was always toward the rear, in the direction of the garden. In observing many early house plans of the town we become aware of the constantly active horizontal spread of the Williamsburg house throughout the eighteenth century,* which reveals, we believe, a steady improvement in living conditions and a rise in the standard of comfort and convenience in the local community. This is definitely noticeable immediately before and after the Revolution. In addition to this, with the advance of the eighteenth century, imported furniture and accessories became more and more common and a great number of new types of furniture and furnishings made their appearance, as well as more varied and space-consuming dress for both men and women.

The alterations made to a house from decade to decade often reveal a sequence of architectural fashions. In the case of the Brush-Everard 22. House we observe that the house at the beginning had an austere front and steep roof, that it was built with the simplest of materials and without any ostentation. Subsequently an ornate stairway with surprisingly sophisticated and at the same time Baroque characteristics was introduced. At a still later date we find some traces of Greek revival details in the broad molding that surrounded a rear doorway. As an accompaniment to the Greek revival episode, a Gothic revival office building came into being near the north end of the house at some time after the middle of the century. Mr. R. M. Hughes, Jr., a former resident of the houses mentions this as having been built by his grandfather at some time before the Civil War.

The last of the additions but not the least, the porch, extending across the entire front of the house, was gaily embellished with cut-out brackets in a true Victorian manner. This was slyly referred to by visiting Northerners as in the bracketed style of General Grant.

THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE A "STATUTE HOUSE, SIMILAR IN ITS ORIGINAL FORM TO OTHER EARLY WILLIAMSBURG HOUSES

The original portion of the Brush-Everard House has the dimensions and characteristics of the typical "statute" Williamsburg house. Its size, 20'-0" x 44'-2" is a reasonably close approximation to the 20'-0" x 40'-0" size requirement specified by the building act of 1705.* These dimensions (20' x 40') were, by the way, a minimum requirement -- an owner could make his house larger if he chose to do so.

23.That the house has the two brick chimney stacks required by the act has already been stated. It is of interest that the act should have compelled each builder to erect two chimney stacks. The General Assembly, by this requirement, seems to have intended to determine, to an extent, the interior layout and appointments of the house, since two chimneys would imply two rooms with a fireplace in each. A house with two well-heated rooms would have been a fairly comfortable one in the early years of the eighteenth century.

As has already been noted, the original house was the typical story-and-a-half, single-room-deep, wood frame house with A roof which resulted, in the first half of the eighteenth century in Williamsburg, from adherence to the terms of the act of 1705. It was similar in type, though not in all of its details, to other original colonial houses in Williamsburg, such as Captain Orr's Dwelling and the Bracken House. It has, in its front face, a central doorway with a pair of windows placed nearly symmetrically on either side of this. Five dormers bring light to the "half" story, and these are located approximately over the door and window beneath. In respect to its openings, therefore, the Brush-Everard House differs from Captain Orr's Dwelling and the Bracken House, each of which has three front dormers only. The Bracken House, furthermore, has only two first floor windows, while Captain Orr's has three. These differences in the three houses, which are alike fundamentally, may be looked upon, however, merely as variations upon a single theme.

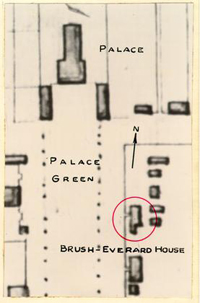

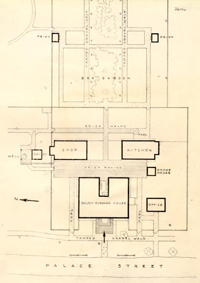

THE BRUSH-EVERARD PLOT AND OUTBUILDINGS

In tracing the history of the plan, which consisted of two half acres, we find no less than nine outbuildings dotted the area between the house and garden (see plot plan on following page). These are partly symmetrical in their placing in relation to the house; the shop balances the kitchen while the center rear doorway of the house is on the axial path that leads directly to the boxwood garden.

These many outbuildings were not built at one time but

rather at intervals. They included a kitchen with servants' quarters above, a

shop, office, dairy, smokehouse, well house and privies. Many of these are to be

found on the Frenchman's Map of 1782.* On the

center

ABOVE,

PORTION OF THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP SHOWING THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE (ENCIRCLED IN

RED) AND THE OUTBUILDINGS ON THE PLOT. AT

ABOVE,

PORTION OF THE FRENCHMAN'S MAP SHOWING THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE (ENCIRCLED IN

RED) AND THE OUTBUILDINGS ON THE PLOT. AT

LEFT,

REDUCED VERSION OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL DRAWING FOR LOT #165, SHOWING THE HOUSE WITH

ITS DEPENDENCIES AND WALKS.

24-a.

LEFT,

REDUCED VERSION OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL DRAWING FOR LOT #165, SHOWING THE HOUSE WITH

ITS DEPENDENCIES AND WALKS.

24-a.

PLOT

PLAN SHOWING BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE AND OUTBUILDINGS

24b.

axis of the houses as was noted above, was a brick path which led between the

kitchen and shop to a large boxwood garden. Other lesser paths extended at right

angles to this axis, and joined the outbuildings to the house and to one

another. The brick and marl paving, which still remains, is surprising in its

extent and varied patterns.

PLOT

PLAN SHOWING BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE AND OUTBUILDINGS

24b.

axis of the houses as was noted above, was a brick path which led between the

kitchen and shop to a large boxwood garden. Other lesser paths extended at right

angles to this axis, and joined the outbuildings to the house and to one

another. The brick and marl paving, which still remains, is surprising in its

extent and varied patterns.

THE NEO-GOTHIC BUILDING (NOW DEMOLISHED) WHICH WAS BUILT BY SYDNEY SMITH NORTH

OF THE BRUSH-EVERARD HOUSE AND USED BY HIM AS A LAW OFFICE. LATER COLLEGE

STUDENTS OCCUPIED IT.

THE HOUSE EXTERIOR DISCUSSED IN DETAIL

BRICKWORK

I General

What is included

The brickwork used in and about the Brush-Everard House consists of the following:

- 1.Foundation walls

- 2.Bulkhead walls

- 3. Two chimney stacks

- 4.Hearths

- 5. Entrance steps

- a)Risers for steps of front entrance (west elevation. Treads are of stone.

- b)North and south entrance steps and platforms of covered rear passage. These have wood nosings.

- 6.Miscellaneous exterior paving and walks.

- 7. The paving of the original basement which lies beneath the southwest room and the hall.

Old and New Brickwork

The following old brickwork has been reused in the house: the foundations of the original west part of house; the side walls forming the bulkhead entrance; the north chimney stack and the old, west half of the south chimney stack, above the roof line in each case; portions of the two chimney stacks within the house, particularly the base of the old part of the south chimney; the brickwork of the hearth of the first floor, southwest room and sections of 26. the paving of the original basement floor. Part of this brickwork has remained undisturbed and part has been relaid. The fact of whether the brickwork of a particular feature has been relaid or has remained is place will be discussed under the heading for that feature.

Color and Texture

Old brickwork

The brickwork of the house foundations and chimneys is of different periods and some of that in the basement appears to be of salvaged brick. As one would expect under these circumstances, the brick color varies considerably, ranging from a buff to a deep red. There is some evidence of glazing but this is of infrequent occurrence.

New brickwork (hand-made reproduction of the old)

This tends to be of a fairly deep red. None of these new bricks have glazed faces.

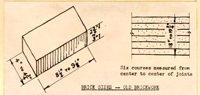

Brick Sizes

Old Brickwork

The sizes shown in the following diagrams were taken from measurements made of the brickwork of the west foundation wall.

Brick bond

The bond of the foundation brickwork, old and new, is English. It was not possible, in the case of the portions of the chimney stacks showing above the roof, to carry out the brickwork in a regular Flemish bond, so that a "mixed" bond was used.

Rubbed or gauged bricks

No rubbed or gauged brickwork has been used in the building.

Mortar

Old brickwork

The undisturbed old brickwork is laid up with oyster shell lime mortar. It is grey in color. The joints are tooled.

New brickwork

The new face brickwork is laid in special colored oyster shell mortar and the joints are tooled. The mortar color and joints were made to match those of the existing old brickwork. A sample panel showing the tooling of the joints and the color of the mortar was prepared and received the approval of the Architectural Department before the work was started.

II Foundations

Old foundations

The foundations at the old west, rectangular part of the building have been left as they were found. Very little repointing or repairs was necessary. These old foundations, when first built, extended only a short distance into the ground. When, sometime after the construction of the original two-room house, a basement was dug beneath this, the builder deepened the existing foundations by placing the necessary supplementary brickwork beneath them. In consequence of the difficulty involved in doing this, the added parts of the foundation walls were, particularly on their outside faces, very irregular. To strengthen the foundation walls and at the same time to waterproof them, the architects of Colonial Williamsburg, after raking the joints of the brickwork to a depth of from 1" to 1½" and cleaning down the surface, poured 29. against the face of the brickwork a concrete slab about 4" thick. This slab starts about 4" below grade and runs down to a point about 6" below the point between the bottom of the brickwork and the concrete wall with which portions of these foundations of the original part of the building were underpinned.

It is of interest to note that the underpinning mentioned above, because of the necessity of supporting the brick walls until the concrete had hardened sufficiently to carry them, was run "piecemeal," that is, it was poured in sections, leaving between these sections "piers" of undisturbed earth to serve as temporary support. When the concrete of these first sections had hardened enough to bear the weight of the building, the earth piers were removed and the remainder of the underpinning wall was poured. This underpinning, it should be noted, was not continuous. The corners of the old foundation wall and other parts of it which appeared weak and to need strengthening were underpinned but the remainder was left without supplementary support.

Bulkhead walls and steps

The "cheeks" or side walls supporting the wood superstructure of the bulkhead and forming the bulkhead stair enclosure are of old brick, all of which was found at the house, but only a portion of which was derived from the bulkhead walls themselves. The foundation walls underground are the original 18th century walls. The cheeks of the bulkhead had been much repaired and contained many late brick. Consequently, the bulkhead walls above grade were completely relaid. A few of the old bulkhead brick were used in this process, but the majority of the hand-made brick were salvaged from other parts of the Brush-Everard foundations. The bulkhead steps are of new brick with new oak nosings. That these steps originally 30. had oak nosings was evident from the presence in the old cheek walls of the notches which once received them.

New foundations

By "new foundations" is meant the foundations under both the old north wing of the house and the foundations under the new south wing. The brickwork of these walls is new hand-made brick, as has been said before. The upper part of this wall, to a depth of about 9½", is solid brickwork. Below this, to a point a few courses below grade (the depth varies at different points about the house due to differences in the grade level), the brickwork consists of a brick facing merely, resting on a shelf in the concrete foundation wall and backed by concrete. The concrete foundation wall is supported by spread footings the bottoms of which are about 9'-4" below the first floor level of the house.

Archaeological evidence used as

basis for location of new portions of building.

(See Archaeological Report, Block 29, Area E, Brush House and Outbuildings.)

Front entrance stoop

The reconstructed front entrance stoop is based, in size and materials on the brick remains of an early stoop found beneath the modern front porch on the west side of the house. The remains were sufficiently well preserved to suggest that the stoop had had a stone platform and stone steps with brick risers, and to enable the architects to determine the approximate original size of the platform as well as the number of steps, with the width of the treads and height of the risers.

Foundations of south wing

After the removal of the modern southeast addition, the foundation remains beneath and adjacent to this were investigated. At the rear of this area, and lining up with the rear foundation wall of the north wing, a foundation wall of colonial origin, 9" thick, was found, together with other, still deeper foundations, as has already been stated on p. 17. The upper foundation was 18'-0-¾" wide, which was almost exactly the width of the north wing. Side walls of the same thickness and period continued from the corners of this wall westward to the back wall of the house proper. These foundations were quite evidently the foundations of a wing corresponding in size and position to the north wing of the house. It was assumed from this that the house, at some time in the 18th century, had been U-shaped, and consequently the once-existent south wing was reconstructed in the "image" of the north wing.

Immediately to the east of the base of the south chimney and backed up against it was discovered the foundation of a brick chimney of the colonial period which, since it was not bonded with the brickwork of the existing chimney, had evidently been added after the original part of the south chimney was built. This formed the basis for the construction of the new chimney of the south wing which was united with the existing chimney to form a single T-shaped stack.

Brick Platform and steps of the covered rear passage

Between the north wing and the foundations of the

south, a considerable number of brick fragments were found at varying

elevations. The study of these fragments, together with a consideration

31a.

Rear

(east) side of Brush-Everard House following the removal of the late addition.

The weatherboarding of the gable end of the north wing, seen here, is typical of

the siding found generally on the exterior of the house. Some of this was beaded

and some unbeaded, and much of it was quite late. All of this weatherboarding

was replaced by new material.

Rear

(east) side of Brush-Everard House following the removal of the late addition.

The weatherboarding of the gable end of the north wing, seen here, is typical of

the siding found generally on the exterior of the house. Some of this was beaded

and some unbeaded, and much of it was quite late. All of this weatherboarding

was replaced by new material.

Old

foundations of the once-existent south wing discovered upon removal of the late

addition mentioned above. The foundation of the chimney, which served this wing

is seen at the upper center of the picture. These foundations furnished the

basis for the reconstruction of the south wing.

32.

of what would have been logical requirements of the house, lead to the following

conclusions:

Old

foundations of the once-existent south wing discovered upon removal of the late

addition mentioned above. The foundation of the chimney, which served this wing

is seen at the upper center of the picture. These foundations furnished the

basis for the reconstruction of the south wing.

32.

of what would have been logical requirements of the house, lead to the following

conclusions:

- 1.That a pair of brick steps (2 risers) spanned the distance between the north and south wings, starting at a point about 3 feet back of the east faces of these wings.

- 2.That these steps gave onto a platform paved with brick which occupied the space between the steps and the rear of the main part of the house.

- 3.That, resting upon this platform were 3 sets of entrance steps, one giving admission to the rear of the hallway of the main wing and each of the other two serving as a means of approach to a door in one of the wings.

No archaeological evidence existed for the steps of the new south wing but a convenient entrance to this wing would likewise have been desirable in the 18th century, and consequently a flight of steps similar to those of the north wing was placed here also.

The steps leading to the main rear entrance were necessary to enable one to approach the door, and, thus they were built even though the evidence for them was not at hand. Stone was used for 33. these rather than brick to link them in character to the steps at the opposite (front) entrance to the house.

Brick drips

Adjacent to the southeast corner (south side) of the excavated foundations of the once existent south wing, a short fragment of what was identified as a brick drip was discovered by the archaeological investigators. It was assumed from this that the house, like several others in Williamsburg, had these flat, 3-brick-wide lengths of paving to receive the rain water from the roof. These would have prevented the water from furrowing the ground surface next to the building and seeping down into the foundations and thence into the basement. Drips of this type have, therefore, been placed about the house at the points where they would have been needed, viz., on the ground adjacent to the foundations and beneath the eaves on the west side of the house, beneath the ends of the house and the brick paving which surrounds the entrance steps, and also along the north foundation wall of the north wing and the south wall of the south wing.

Brick hearths

These will be discussed in detail in the section of the report which treats of the interior of the house.

Brick paving of basement

In the restoration of the basement which existed in the 18th century (that part of the present basement which lies beneath the southwest room and the hallway) the rather extensive areas of old brick flooring which remained in place were left largely undisturbed and the spaces between these areas where the 34. brick were missing were filled in with new brickwork made to resemble the old. Thus the entire floor of the old portion of the basement is now paved with brick.

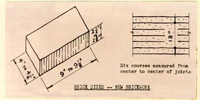

Brick and marl paving of walks and paths

As was remarked on p. 24, an unusual amount of brick and marl paving was found about the Brush-Everard House and outbuildings. In fact, no other Williamsburg house, large or small, has been found to have had so much brick paving and so many marl walks. From these relatively well-preserved remains of paving, it was fairly easy to restore and reconstruct the brick-paved areas and the brick and marl walks which once existed on the lot. (See plot plan, page 23-A, showing, together with the buildings the restored or reconstructed paved areas and walks.)

The largest, by far, of the paved areas restored is the extensive rectangle of brick paving, a large part of which was found intact, which existed in colonial times between the rear of the house, on the one hand, and the shop and kitchen on the other. This area was, in fact, so large (as restored it measures approximately 16' x 86') as to suggest that it may have served purposes other than that of a walkway alone; it may have functioned, for instance, as an outdoor work space in relation to the shop and kitchen.

There are other lesser areas of brick paving, notably about the reconstructed dairy and well, and some brick walks in addition. There are also on the lot numerous marl walks -- about the house and in the box garden especially.

35A considerable variety was exhibited in the manner in which the brick of the paved areas were laid. Examples of the principal patterns represented in the brickwork found about the house and outbuildings are shown in the series of diagrams at the right. One of these diagrams shows, in additions the texture of the marl paths found on the lot.

Other uses of brickwork

Other old features or facilities constructed of brick were discovered on the Brush-Everard property, such as a portion of a drain which was found running in a northerly direction some twenty or more feet northeast of the house, and a retaining wall, thought to have been part of the enclosure of an artificial lake in the one-time rather extensive garden appertaining to the Brush-Everard House, which was found at the extreme northern limit of the property bordering the extension of Scotland Street (Palace 36. Lane.) These features, as well as the outbuildings and garden, however, are not properly the subject of this report which deals with the Brush-Everard House alone.

STONEWORK

Front entrance steps and platform and steps at rear entrance to main part of house. These features have been executed in Indiana limestone of a "rustic gray" color and with a rough chat sawn finish. The stones are set on a full bed of white cement mortar and the backing and jointing are also of white cement mortar. The separate stones are "locked together" by means of wrought iron cramps set in lead.

Indiana limestone was used since it approximates fairly closely the English Purbeck or Portland stone. The nosing profile in the case of both the front and rear steps is reproduced from an old stone step fragment that appertained to the house east of the Paradise House.

EXTERIOR WALLS

The walls of the house are of wood framework, covered on the exterior with beaded weatherboarding and finished on the inside with plaster. The old framing remains in the old portions of the building, i.e., the main front part and the north wing. The old framework of both the walls and floors of these portions has been strengthened, where it was found necessary, by the addition of new joists, studding and sills. The framework of the new south wing is, of course, completely new. 37. The old wood lath and plaster were removed throughout the building and all of the rooms were completely replastered with gypsum plaster applied on paper-backed galvanized welded wire lath. Aluminum foil was placed as insulation in all of the exterior walls.

The use of steel to strengthen the framework

Steel was used in certain positions in the old parts of the building to strengthen the framework - steel angles and hangers to furnish a more secure bearing for the old joists, and steel angles running the length of certain of the main transverse beams to strengthen these. In the latter cases the beams were "flitched" or "sandwiched in" between two steel angles. The central portion of the framework of the old front part of the house was strengthened and stabilized by the use of two steel hangers, that is, rods, 1 1/8" in diameter, which were run in the walls of the stair hall from steel plates located in the roof ridge down through the building to similar plates beneath the sills of the first floor. Each rod was interrupted in its two-story length by two turnbuckles which permitted it to be drawn tight for the purpose of stiffening the framework. In effect these steel hangers converted the framework of the stair hall walls and the roof rafters immediately above them into trusses of a sort and thus strengthened the entire structure.

Brick nogging

Brick "nogging" was found on the first floor between the studding of the north and west walls of the northwest room and of the north wall of the north wing when the plaster was stripped from these walls 38 to make possible the examination of the wood framework. This nogging consisted of old bricks of varying lengths set upright on their sides between the studding of the walls. It is believed that this served the purpose of insulting the cold north and west walls of the rooms. The nogging was removed during the restoration of the building and, as stated above, aluminum foil was placed as insulation in these and other exterior walls of the house.

Weatherboarding

As was remarked above, beaded weatherboarding forms the exterior covering of the outside walls of the house. This weatherboarding, which is new throughout, is applied over felt and blind nailed to the studs. Exposed nails (reproductions of antique nails with hammered heads) were used in addition to the blind nailing. The weatherboarding of the old front of the house has an exposure of approximately 7". This rather unusual exposure was based on the discovery in a well protected location just below the cornice bed mold of a piece of old weatherboarding having paint and weather marks which indicated that its exposure had been 7". The exposure of the weatherboarding of the 39. wings, however, is between 5½" and 6", The latter boarding was made narrower to differentiate it from the siding of the main part of the house and thus to suggest that the wings were built at a period different from that of the main body of the building. In conformity with the customary practice in Williamsburg houses of the 18th century the lower edge of the weatherboards which are adjacent to window sills line up with the bottoms of the sills and the beads of the boards are approximately continuous with the beads of the sills.

New weatherboarding was substituted for the old throughout the house since the condition of the weatherboards found in place was considered too poor to warrant the retention of any of them. The old boards were, furthermore, a melange of beaded and unbeaded boards of varying widths and of dubious age.

EXTERIOR TRIM

A considerable percentage of the exterior trim at present found on the house is old though it has been repaired. In making these repairs the principle was followed of preserving scrupulously every old part that was sound. When, for instance, a portion of a molding was still usable, this was retained and only the deteriorated part replaced by new material.

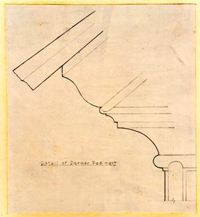

Main cornice, west front

The main front cornice is a modillion cornice, consisting of a crown mold, fascia, a course of rectangular blocks (modillions), the centers of which are about a foot apart, and a bed mold. It was necessary to renew most of the existing old cornice, but the details of the latter were carefully followed in making the new 40 parts. The modillion blocks are new but they were located over the marks of the original modillions on the old soffit board of the cornice. The bed mold is partly old and partly new; the old portion is the part on the north side of the west front and this comprises a little less than one-half of the entire bed mold. The remainder of the cornice is new.

Cornice of the wings

The cornice used on the wings has moldings of the same character as those of the front cornice but it has been simplified by the elimination of the modillion blocks, and its elements generally have been somewhat reduced in scale. The portion of the cornice at the north eaves of the north wing is, to a great extent, old but it was necessary to patch the crown and bed molds. Its companion on the south side of the same wing is new throughout. The corresponding members of the new south wing are also entirely new. These new sections of the cornice are patterned closely after the old member of the north side of the north wing. The crown molding used at the eaves line of the shed roof covering the open rear passage is likewise new.

Cornice end boards

There are no cornice end boards as such; as in the case of the old cornice of Captain Orr's Dwelling, two of the gable-end weatherboards at the cornice level are extended beyond each corner of the building to receive the upper members of the cornice, i.e., the crown mold and fascia. This leaves the modillion blocks exposed to view when seen from the sides. The 41 bed mold of the main and wing cornices, as is the case with this member of the Captain Orr cornice, is returned against the building face of the front on which it is located.

Barge boards

The barge or verge boards which follow the rake of the roof on the four gable ends are the typical flat boards with lower edge beaded as found on most Williamsburg buildings. In all cases they taper in the direction of the roof peak. The barge boards of the old front part of the building are somewhat wider than those of the wings, their widths at their lower ends being approximately 6" and 5" respectively.

The barge boards on the west sides of the gables of the main building terminate at their bases in ogees or reverse curves, while those on the east sides of these gables are cut off vertically where they ran into the roof projections of the wings.

The rake boards of the wings are cut off at their bases on a diagonal which parallels the inclination of the crown mold, the ends of which are received by the rake boards.

The barge boards throughout are new.

Corner boards

The corner boards of both the main building and the wings are of the "two-way" type -- that is they have the same width on each of the faces forming the corner. The width of these boards is 3#x00BC;" and they are provided with a bead at the corner where they join. 42. At the points on the north and south faces of the building where the main house meets the wings, the weatherboarding is interrupted by so-called "vestigial" corner boards running from the bottom of the weatherboarding upward to a point even with the base of the crown mold of the wing cornices. These are beaded on their east sides.

At the time the measured drawings of the house were made a vestigial corner board existed on the south face between the main house and late addition, which was removed in the course of the restoration of the house. On the north side, however, there was no such feature and the weatherboarding continued without interruption from the front to the rear of the house. In restoring the dwelling the architects used vestigial corner boards on both the north and south faces to call attention to the fact that the wings were built at a later date than the main house. This followed a frequent colonial practice of leaving the corner boards in place when an addition was made to a house. Such cornerboards were, furthermore, a necessity in this case since the exposure of the weatherboards of the main house and the wings is different, so that the boards of the two portions do not line up.

The corner boards in all cases are new.

ROOF

The roof as restored

The roof of the main part of the building (the oldest portion) is a typical A-roof with gable ends. The angle of the slope is 47½°. The two wings are also covered with A-roofs; these 43. terminate on their west ends in the roof of the main part of the building, and on the east in gable ends. The slope 50° is slightly more than that of the main roof.

The outside court at the rear of the house is covered by a shed roof which runs eastward from the eaves line of the main roof to the east faces of the two wings and, in a north-south direction, from the south wall of the north wing to the north wall of the south wing. Its slope is 19°. (See next page).

The framing of the roofs over the main part of the building and the north wing is old. Where it was deemed necessary this old framing was strengthened by the addition of new rafters.

The framework of the roof of the new wing is, of course, entirely new.

All portions of the roof have been covered with round butt Mohawk asbestos cement shingles. The appearance of these shingles, when they have weathered, is reasonably close to that of the cypress shingles which would have been used in the 18th century. They were used here, as they have been used in most other restored and reconstructed buildings of Williamsburg, because they are completely fireproof. They are laid 5-½" to 6" to the weather on wood sheathing covered with 4-ply felt.

Where the chimneys penetrate the roof flashing and counterflashing of sheet lead was used. At most other points where flashing was required, i.e., the junction of the vertical dormer walls with the roof; roof valleys; roof ridges, etc. 16 oz. hot rolled copper was used as flashing.

The Archaeological Basis for the Shed Roof Over the Rear Passage

The illustration included here, a photograph of the south side of the north wing showing the framework exposed after most of the weatherboarding had been removed, indicates clearly that a shed roof at one time covered the rear court or passage. Notches which must have received a sloping roof rafter are clearly visible in the studding, the diagonal brace and the post at the southeast corner of the wing. If these notches in the picture are connected by a straight line, the line is seen to be a diagonal joining the corner post and the eaves of the east slope of the main house roof.

VIEW

OF SOUTH SIDE OF OLD NORTH WING, SHOWING FRAMEWORK REVEALED AFTER REMOVAL OF A

LARGE PART OF THE WEATHERBOARDING FOUND IN PLACE. THE NOTCHES WHICH WERE THE

CLUE TO THE EXISTENCE IN A FORMER DAY OF A SHED ROOF OVER THE PASSAGE BETWEEN

THE TWO WINGS, AS WELL AS THE ORIGINAL DOOR FRAME, ARE CLEARLY VISIBLE IN THE

PHOTOGRAPH.

VIEW

OF SOUTH SIDE OF OLD NORTH WING, SHOWING FRAMEWORK REVEALED AFTER REMOVAL OF A

LARGE PART OF THE WEATHERBOARDING FOUND IN PLACE. THE NOTCHES WHICH WERE THE

CLUE TO THE EXISTENCE IN A FORMER DAY OF A SHED ROOF OVER THE PASSAGE BETWEEN

THE TWO WINGS, AS WELL AS THE ORIGINAL DOOR FRAME, ARE CLEARLY VISIBLE IN THE

PHOTOGRAPH.

Quite evidently a shed roof, which ran from the main roof eaves to the east front of the two wings had at one time covered the open space between the wings. A new shed roofs has, therefore, been placed over the passage between the two wings, at the level and with the inclination of the old roof. This roof has been plastered on the underside in conformity 43b. with an 18th century method of treating roof soffits. An old example in Williamsburg of such a plastered soffit is that of the roof of the westernmost porch on the south side of the Coke-Garrett House.