John Blair House Architectural Report, Block 22 Building 5Originally entitled: "The John Blair House and Outbuildings Block 22, House 5, Lot 36 Architectural Report"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1498

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

THE JOHN BLAIR HOUSE AND OUTBUILDINGS

Block 22, House 5, Lot 36

Architectural Report

REFERENCE

JOHN BLAIR, SR.

and

JOHN BLAIR, JR.

THE BLAIR HOUSE

(Block 22, Col. Lot 36)

- Research Report, by Dep't. of Research and Records, Dec. 12, 1943.

- Dictionary of American Biography; See James Blair, John Blair, Sr. also John Blair, Jr.

- William and Mary Quarterly, First Series, Vol. 7, pp. 133, 134.

- York County Records. Bk 22, Wills and Bk. VI, Deeds, p. 101 Inventories. See also files covering lot ownership and Transfers, in Library, Dep't of Research and Records, Col. Williamsburg.

- Virginia Gazette

Hunter Editor, Dec. 5, 1751

Purdie & Dixon, Sept. 2, 1773

Clarkson & Davis, July 3, 1779 - Business Accounts of Humphrey Harwood, Bricklayer, Carpenter, 1789 - 1792 (Photostatic copy of this document is in Library Dept. of Research and Records).

- Insurance Policy of 1809 with physical description of Blair House of that date. The Lot (36) is under name of Robert Andrew who married Mary Blair, daughter of John Blair, Jr. in 1795.

- Recollections of the Blair House by John S. Charles and of Mrs. Victoria Lee who support the theory that the Blair House underwent no considerable exterior change during and since 1860.

- Frenchman's Map, showing a house and outbuildings on Col. Lot 36.

- Diary of John Blair, Sr. (William and Mary Quarterly, VII, 1-17 with notes by Lyon G. Tyler.)

- Frederick Horner, History of the Blair, Banister and Braxton Families (1898) has a chapter on "John Blair, Sr." and John Blair, Jr. adding little to our information about the John Blair.

- Useful sketch of John Blair, Jr. in Hugh Blair Grigsby's Convention of 1776 (1853).

- Journal of the House of Burgesses, 1750-1770.

- L. G. Tyler, Williamsburg, The Old Colonial Capital (1907). A discursive account, containing some information on the 3 Blairs and on the so called "Blair House".

THE TWO JOHNS BLAIR

John Blair, Sr. (1687-1771)

John Blair, Jr. (1732-1800)

Three men of the name of Blair, all of the same blood, filled continuously the highest civil offices of the colony, the commonwealth and the Union from 1687 to 1800, a period of one hundred and thirteen years. For one hundred and seven years the name of Blair in an official capacity was closely joined to the building history of the main edifice of the College of William and Mary at Williamsburg.*

The two Johns Blair, father and son, have also been associated by tradition, although not confirmed by record, with the dwelling that has long been known as the Blair House, situated on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street, Block 22, Lot 56. The house has considerable historic interest because of the Blairs, even though the occupation of the house by John, Jr.** is alone sustained by our records.

3As a preparation for the architectural discussion of this house, a few memoranda are given, touching on the lives and interests of these two men.

John Blair, Sr. was the son of Archibald Blair who was a brother of the fiery and aggressive James Blair, the founder of the College of William and Mary at Williamsburg. It is probable that the senior John Blair was born in the colony of Virginia. He was educated at the College of William and Mary shortly after a fire had swept away the original building. In 1713 - at the age of 26 he held the position of Deputy Auditor - General pro tem. From 1734 to 1740 he was a member of the House of Burgesses, and in 1745 he was appointed member of the Council, soon to become its President. He was twice acting-Governor of the Virginia Colony.

John Blair, Sr. was in narrow circumstances until he and his children received about [UNK] 10,000 by will of his uncle, James Blair, who died in 1743. With the expansion of Virginia, Blair, Sr. became interested in lands of the Western part of the Colony. In 1745 he and associates acquired 100,00 acres, west of the Fairfax line. This land was the basis of a small fortune. He married Mary Monro, had 10 children and died at the age of 85.

His diary for the year 1751 reveals the senior Blair as a typical Virginia public man of that day, interested in local building construction, in gardening and in minor matters of town 4 and country as well as with national affairs. (See Diary Extracts of John Blair, Sr. attached.)

John Blair, Jr. was born in Williamsburg and remained a resident of the town throughout his lifetime. He attended the College of William and Mary and later, on 1755, went to London where he continued his legal training at Middle Temple. Returning to Virginia he soon entered the House of Burgesses, representing William and Mary College, in English fashion, from 1766 until 1770. He became Clerk of the Council after June, 1770

In 1769, during a period when the House of Burgesses was dissolved, he was one of a patriotic group, including Washington and Bland, and a notable body of "merchants of Williamsburg", which held a spirited meeting at the Raleigh Tavern and drafted the non-importation agreement on certain specified goods from Great Britain until the Act of Parliament, which "imposed a duty on tin, paper, glass, and painter's colours, was totally repealed."*

5John Blair, Jr. was a member of the Committee of twenty-eight which framed a declaration of rights and a plan of government. He served on both Council and Court for a brief time. In 1786 he was selected by the General Assembly of Virginia to attend the convention in Philadelphia for the framing of a Constitution of the United States. As a termination of his public career he was appointed by Washington as Associate Justice of the Supreme Court from which high office he resigned in 1792, because of failing health, returning to his home in Williamsburg. Here he lived until his death, August 31, 1800.

There are no striking anecdotes to enliven the personalities of the two Blairs. They left little published material and, curiously enough, no printed speeches.

The diary of John Blair, JSr., jotted down on a calendar for the year 1751 and covering his comments of one year.* We get glimpses of his interest in the rebuilding of the Capitol in which he records, April 1, 1751 "I laid a foundn Brick at the Capitol....Found the Capitol as I left it the 3rd.....got door cases put up....lay bricks for grand steps...Skelton fired ye last Kiln for Capitol....I laid the top Brick, N. End....2nd. floor not yet begn to be raised."

In the foregoing listing of some of the entries there is indication of a keen interest in several unidentified building projects. This interest extended to assistance to others in construction advice or actual 6 building, such as, "I promised Mrs. Hendriken to try to build a house for them in the fall....Began to lay bricks in mortr at B's house......" Aug. 30, 1751 "First course of Mr. B's house laid.....My chimney begn..." The inference can be made that the house for Mr. B. is the Blair house, considered in this report of one of the several houses on lots mentioned in the Research Report; however, there is at this time no supporting evidence connecting the name of John Blair, Sr. with the building on Lot 36, Block 22. "It can be established," according to the Research Report, Dec. 20, 1943 "that John Blair, Jr. lived in the house now standing on this lot."

The further study of documents is indicated as desirable in order to relate, with final certainty, the name or names of John Blair with lot 36, Block 22. Furthermore, the name of John Blair has been associated with the ownership of lots, east of the Palace, as well as with the Archibald Blair lots on Block 29. The nature of ownership requires clarification and further interpretation by the Research Department of Blair Williamsburg. Further study of John Blair items and John Blair property ownership is contemplated.

Significant Facts

Concerning

THE BLAIR HOUSE

History, Construction, Alterations

Block 22, House 5, Col. Lot 36

Accredited To A Date Around 1750

The Blair House was restored by Colonial Williamsburg, Inc., in 1929.

The building had been remodeled extensively by the College of William and Mary in 1923. Interior partitions at that time were altered and some rebuilt. Dr. E. G. Swem of the College, in speaking of the house and its condition before these changes were made in 1923, said that all walls and partitions were found to be of poplar wood with infilling of 4 inch brick nogging.* He further affirmed that, in the course of the house alteration and repair, some partitions were placed in new locations, most of the "nogging" was eliminated and new framing members added. The basement walls were altered slightly in their position, patched or largely rebuilt. The condition of the building, when the College acquired it, was in general fair; with disintegration mostly confined to wood sills and framing members at the lower part of the building.

The greatest loss during the many alterations of the building's history was the removal of all interior paneling, trim, mantels, chair-railing

CLAPBOARD

CLAPBOARD

SIDING (OAK)

9

and other "finish woodwork". The original exterior cornice had also vanished. Some fragments of woodwork, together with traced outlines were found. These were of assistance in establishing the nature of interior woodwork.

There is an unsupported tradition that the two stone flights of steps at the two entrances did not belong to the house as first built but came, originally, from the first theatre of Williamsburg. Lyon G. Tyler adds to the uncertainty by saying that the Blair House stone steps came from England. He probably infers that the source of the stone was England. This is undoubtedly true since Virginia had no satisfactory building stone in this locality.

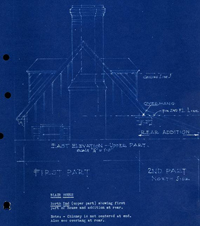

The house was built at two different periods. Basement walls indicated a first form, approximately 36 feet in length and 18 feet in depth, also a later one.

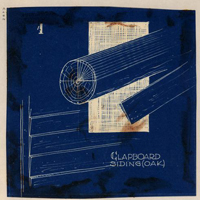

Weatherboards of oak, split to thin strips were found attached to a wall which had originally been an outside, west end wall of the house, imbedded in what was an original north wall discovered at the time the house was stripped for restoration.

The addition or "Lean-to" at the rear of the house appears to have been attached at a very early date, possibly while the building in its first form was being finished. The house was originally planned so as to have an overhang of approximately 2'-6" at the rear. It was on account 10 of this overhang that the comb of the roof is "off center", in other words - the center is nearly 18" towards the rear.

There is no document available to establish the year when the house was lengthened to its final form. This enlarged size is first supported by Insurance Policy No. 989, p. 7 in book of Insurance Policies, (Mutual Assurance Society of Virginia)* This policy, dated 1809, shows that a one-story wooden dwelling house, 64 feet by 28 feet; a detached kitchen, 18 feet to the rear of the house, a laundry and a wooden office 24 feet by 16 feet, stood on the lot.

The woodwork details of the Duke of Gloucester Street front are believed to be substantially as they were in the 18th century. It must be borne in mind however, that weatherboarding had been replaced during the late history of the house and at earlier intervals, and further repairs were made during the process of restoration. The dormers, discussed in detail further on in this report, were reconstructed by strict conformance with the form and fenestration of the early ones, belonging to the house. In all cases, the architectural details of similar parts, found in Williamsburg and vicinity, were followed.

The foundations were partly reconstructed for structural stability. Also the central chimney was rebuilt, and the east-end chimney repaired. These repairs and changes were done with use of "old brick" from the site or from the warehouse supply.**

BLAIR HOUSE

BLAIR HOUSE

North End (upper part) showing first

part of house and addition at rear.

Note:--Chimney is not centered at end.

Also see overhang at rear.

The principles of "full restoration", with reference to the Blair House "were considered for the exteriors only". This rule, incidentally, has been followed consistently in restoration of other houses in the Colonial area of the town. In the light of this principle, all exterior door-frames and their accompanying sills, where they replaced older ones, have been shaped "out of the solid" framing timber and joined by "mortise, tenon and peg". Window frames and sills when renewed, are also made of solid wood and have the same jointing treatment. Wherever possible, old woodwork is retained and, if possible, patched. Interior work is not so strictly authentic in the manner of workmanship methods. In design and contour, the interior woodwork faithfully followed precedent of the period found in Williamsburg and vicinity.*

13The Blair House - Architectural Description

The Blair House, No. 5, Block 22, appears to have been continuously known by that name from the eighteenth century on. In this report we are almost exclusively concerned with the architectural description of the house, not with the designation of Blair family ownerships.*.

The Blair House is of considerable architectural interest on account of its having retained much of its outward eighteenth century appearance.** It is also a typical story and a half Williamsburg house as specified in the enactment of 1705 in Hening Statutes, "that whosoever shall build in the main street of the said city of Williamsburg . . . . . shall not build a house less than ten foot pitch and the front of each house shall come within six foot of the street. . . . . ."*** and ****

14The house is of braced-wood framing having mortised connections, faced with weatherboading, with approximately 7" exposure. There is a chimney at the east end of the house, and from the center of the existing house there was a second square shaped chimney that appears to have been rebuilt and altered from an older form.* There is evidence to indicate that the house was built at two or possibly three periods.

First of all, the house was added to at the north (rear) side changing the contour of the roof from an "A" shape to one with a "lean-to" at back. The second evidence of change consists of the chimney location at the near center of the present house. This chimney location was originally the west end, see drawing with this report. Ample proof of this first house was discovered when inner walls were partly stripped to the bare framework in 1930-31. At that time very old weather boards of oak, split to thin feather edged pieces were found attached to what was revealed to have been the original west wall of the house. This is discussed elsewhere in this report.

The shed extension at the north side was probably added early in the house history, "and really can be considered contemporaneous with the original house."** There was a roof overhang at the rear - 2' - 4". It appeared, from further consideration of appearance and framing, that the leanto was applied as a "revision" before the house was completed.

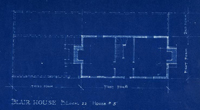

16THE HOUSE PLAN

The plan of the Blair House in its original form was one room deep, and consisted of a center hallway with stairs and a room on either side. This familiar floor arrangement was so common in Williamsburg that it may be termed "typical". The stairway gave access to the second floor with its two upper bedrooms, one on either side of the hall. This followed the downstair arrangement excepting that second floor rooms were smaller because of their situation within the roof slope.

The house in its old form was approximately 36 feet in length and 18 feet in depth, a proportion of one to two. This does not take into account the first ground-floor enlargement of the house by a 10 foot shed-roof extension to the rear. Just what 18 century use was made of this ten foot increase in depth is not known.

A more considerable addition to the plan was made at some time in the late 18th century. The addition consisted of 26' - 6" added to the length. This became the house outline that we believe was shown on the Frenchman's Map of 1782. There was still another separate structure on the plot, a small square building that may have served as the "Blair Office." At the extreme easterly limits of the plot on the same map a long, rectangular building is shown. The individual who may be interested in the ownership of adjacent lots in Block Report on The Blair House, December 12, 1943:

EXTERIOR WALLS

Walls of the Blair House were of poplar and pine studs, braced at the four corners, and with partial bracing found at what was the wall angle of the house in its first (18' x 36') shape. Much of the wall framing was replaced by substitution of new timber, without disturbing the 17 wall thickness or external dimensions of the house. In this process of reconstruction, floors that had acquired a slope or sag were levelled and walls were brought to an approximately plumb condition.

There was discussion of the danger that lies in an overscrupulous regard for "freshening up" old woodwork and rebuilding parts which while solid are almost worn through or otherwise acquired an "aged" and "out of shape" condition through long usage and hard wear. A decision was since gradually reached to leave untouched - as much as was physically possible - the condition and appearance of age acquired by a house, by floors, door sills, chair rails, stairs (treads and railing) and in general all wood surfaces." In the Blair House, Duke of Gloucester Street frontage - the principle of "preservation of old woodwork" as opposed to "reconstruction" has been faithfully carried out.

ROOF TYPE and characteristics

The roof of the John Blair House is "A" shaped, with a slope, approximately 50 degrees, designated in handbooks of carpentry as a "true" (or common) pitch.* The roof framing consisted of a familiar 18th century "timber frame construction". Roof rafters were approximately 3½" x 6" in size. The second floor rooms were built within the roof slope. Horizontally placed ceiling rafters, tied the roof rafters together and give the roof framing the appearance of the letter "A".

The sheathing boards over which the wood shingles were applied - in its late 19th century condition - were of random width and spaced with a gap of two inches or so between each board. This is exceptional since the original clapboards used as the roofing of the earliest roof surface, were without sheathing boards. Clapboards, lapping over one another at 18 edges and ends were nailed directly on the roof framing.

At the time the restoration work on the Blair House was started, a covering of lapped weather-board shingles of oak was found underneath a layer of wood shingles for the east (old) end of the house. This feather edged method for surfacing the roof is generally recognized as of an early date, although examples of its use continue on down to 1800, mostly however, for outbuildings and where waterproofness and air tightness was not important.*

The substitution of asbestos shingles for wood shingles or other roof surfaces was done for reasons of fire safety and to conform with Williamsburg building regulations, requiring a fire-safe roof.

DORMERS

Examples of early dormers, believed to be original in their design, were found on the north side of the house. These are discussed elsewhere in this report.

As was often the case with early roofs - there was little tangible data to show whether lead, wrought iron or other flashing had been used as

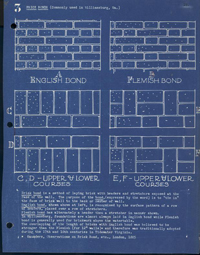

BRICK BONDS (commonly used in Williamsburg, Va.)

BRICK BONDS (commonly used in Williamsburg, Va.)

Brick bond is a method of laying brick with headers and stretchers exposed at the

face of the wall. The purpose of the bond, (expressed by the word) is to "tie in"

the face of the brick wall to the back or center of wall.

English Bond, shown above at left, is recognized by the surface pattern of a row

of headers, placed over a row of stretchers.

Flemish bond has alternately a header then a stretcher in manner shown.

In Williamsburg, foundations are almost always laid in English bond while Flemish

bond is generally used for brickwork above the watertable.

The overlapping of the length of bricks with English bond was believed to be

stronger than the Flemish (for 12" walls)* and therefore was traditionally adopted

during the 17th and 18th centuries in Tidewater Virginia.

* Saunders, Observations on Brick Bond, etc., London, 1805

20

"roof flashing". The probability exists that when split shingles were first applied as a "follow up" for clapboards - that these shingles were woven as a continuous roof covering as was shown in a few early instances in Virginia. Evidences for such woven roofing were not discovered here.

The barge boards and cornice-end stops found on the house when the restoration was carried out were modern. It was decided that these should be removed and that a faithful replica be made of other barge and cornice details in Williamsburg. Examples used for study and reproduction were found on the Captain Orr's dwelling, the James Galt House, and the Orrell House, all of a design-period believed to be approximately contemporaneous.

The corner boards, while altered in recent times, were restored on evidence supplied by some remaining beaded board fragments,* found on the building.

The dormers with their unusual fifteen light sash (see drawing attached) were reconstructed by the use of existing original dormers found on the north side of house. The ones, in place on the south side were late and had been altered. These were replaced by replicas of the north side originals. The original dormers themselves were repaired and not replaced. The west and middle ones on this north elevation were built entirely new on account of their decayed and partly altered condition. 21 The easterly one which served as the model for the others required little in the way of repair, but only a new cornice some patching and a new sill. The sash of dormers throughout were made uniform with respect to number of lights and nature of glass.*

Some few oak strips that served as clapboard roofing to the east dormer were retained in place - built beneath the finish surface of asbestos shingles. Sash frames and sills were joined at angle by mortise and tenon.

The Blair House - Masonry

The foundation walls of the Blair House were considerably altered at various times. These consist of repairs and addition of new walls. They reveal something of the growth of the house; we therefore must continually bear in mind - the history of the house with its original plan - 36 feet in length and 18 feet in width, and later on the addition of 28 feet to its length. These "house history facts" can be perceived by examination of the foundation walls. Such an examination would also disclose a departure from customary practice in building foundations, namely in the difference in certain wall thicknesses. For example, the wall at the Duke of Gloucester Street side is 22" from outside to inside face, while all the other foundation walls, to east, west and north, are the usual 13" thickness. Much of the surface brickwork was found to be uneven in surface, and with several sizes of brick. At the time of the restoration the brick facing was repaired and made more uniform. The actual bricks used were salvaged from the existing wall, supplemented by others obtained from the storage pile of 18th century brick. In matching brick for color and size, it was decided to follow the pattern and color existing on the undisturbed east end of the house.

A few words can be said here concerning the rather consistent practice, in Williamsburg, of using English bond for foundation walls, while upper masonry walls are Flemish. English bond, it is believed, was favored during the eighteenth century for foundations of the 13 inch wall, because of their greater strength. The English bond affords a better transverse tie with bonding carried more completely through the wall. (See drawing #3 with this report.) This, however, is not the 23 case when the walls are 18 inches thick, unless the bricklayer gives himself the trouble to lay the bricks with transverse tie at the center.

Mortar was examined in the old brickwork at the east end and elsewhere. The original mortar was found to be composed of oyster shell lime, together with sand or loam. All mortar for repairs and refacing of brickwork was produced with a faithful following of mid-eighteenth century practice. This applied to the calcination of seashells for lime, the mixture as mortar and the resulting texture of the mortar grit and methods for "tucking" and pointing the joints. The proportion of sand to oyster shell lime varied with workmen. For mortar used in laying stone steps, a "mixture of six parts of lime, one of pure sand, and as much water as may be necessary to form it to a proper consistency." This mortar was used to produce extremely thin joints. In the case of rubbed brick a mixture of marble dust and putty is said to have been adopted. In general mortar for brickwork required a considerable amount of sand in relation to the mortar. A proportion of 3 sand to 1 of lime was common, but not universal. Color was given to the mortar by the color of the sand.

CHIMNEYS

Examination revealed alteration made to the central chimney (formerly an outside chimney stack at the west end of the original house). An early photograph showed the previous and probably the original chimney shape - before alterations and repairs were made by the College of William and Mary, in 1923. In repairing this chimney the contour, believed to be original, was followed. Again, the surface brick, used in the 24 chimney restoration, were old bricks. The lining of flues--however, consisted of present day common brick with modern terra cotta flue lining.

The east end chimney was left undisturbed, excepting for slight replacement of an occasional brick and relaying a few at the top of the stack. On the whole, - this chimney, with its "T" shaped group of funnels,* remains unaltered and with its original 18th century appearance and acquired "aged" surface.

The brick sizes for the Blair House are; width 4-1/8"; thickness 2-3/4"; length 8-3/4". Mortar joints average 5/16" in thickness.

STONEWORK FOR ENTRANCE STEPS

Lyon G. Tyler in his "Williamsburg, The Old Colonial Capitol", (1907) describes the Blair House as "a long framed structure . . . . with two entrances, approached by stone steps, evidently imported from England."** It was evident from appearance, that the stone steps were not original but that they replaced earlier wooden steps. According to unconfirmed tradition they were salvaged from the first theatre of Williamsburg.

The stone steps were subjected to careful scrutiny with the thought that markings on the back of stones might provide a clue to earlier use. The markings (numbers) on under side of stones seem to have been applied when the steps were built, or--it was believed,--when moved from another site to this location. See George Campbell's notes in Archaeological Field Notes.

25During restoration the steps were taken down, piece by piece, measured and refitted. As far as possible, relations of stone to stone as they existed, were followed. Some parts were missing. These were filled out with extra pieces of stone left over from the steps, and recut to correct profiles. A few extra pieces were also obtained from the old stone stored in the warehouse. Mortar joints were darkened with lampblack and protected from moisture absorption on under side by an application of R. I. W. (mastic waterproofing paint). Wrought iron clamps were used to join stone to stone, in accordance with practice of the period.

EXTERIOR DOORS

The Blair House has two front doors, (south side). This fact is not unusual for Williamsburg, which has several examples within the "Colonial area". The "pair of doors" can, possibly, be accounted for by the process of lengthening the house. The first house on the site had its center hall with access to a room on either side. And addition at the end of such a house would require a separate entrance, unless the intervening room were to be converted into a hallway. The frequency of the two entrance door arrangement in Williamsburg is also accounted for by the "one room depth" of many houses of the locality. The two-door front was retained in the restoration and prompted the conversion of the house for use by two separate families.

DOORWAY AT WEST END OF SOUTH FRONT

Of the two doorways, the one toward the west end is wider than the other one, and has old double doors, set in what appears to have been 26 an eighteenth century frame. There is a fixed transom over this double door. The trim surrounding the transom was old, while other doorway trim, found in place - was of recent design. The transom trim was used as the pattern for other door and window woodwork. Since the narrower doorway had various parts changed, it was studied with benefits of the double door-way treatment and made to conform with it as to transom and woodwork. The glazed transom of this sort was partly the result of actual need for light in the hallway. It also served a purpose of design in that it brought the head of the doorway to the same height as the heads of windows. The glass was kept in line with the plane of the doorway. It was more common to have a single row of glass serving this purpose. The dimensions of the glass then frequently followed the glass size of the adjoining sash. Other work on these doorways and doors included the removal of "not very old" wood sills and replacement by sills of eighteenth century design made from the customary "heart yellow pine." The double doors, weather worn and ancient in appearance have the early type "raised panels". These are generally associated with the middle of the eighteenth century or earlier. The single interior doors have "six panels" conforming in appearance, with the original interior doors of the Captain Orr dwelling (Barlow House) in Williamsburg.

It is believed that the contour of panels is a partial key to the age of woodwork. In order to gain a fuller knowledge of such a relationship of paneling and age, the Architectural Department is preparing a collection of moulding and panels (as far as possible, dated). This assembly when completed as drawings and with some actual examples of panel - will be available for examination and study by architects and others interested in the evolution of architectural forms.

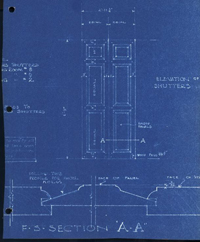

SHUTTERS

Shutters of the late 19th century design and manufacture were in place when the house was restored. Outside shutters, it was believed, were essential to a house placed near to the sidewalk. The window blind on the house exteriors was a common feature of the Virginia houses starting at Jamestown. Very often blinds were added to houses built at a much earlier date. Inside shutters occur early in the century, generally with building built of brick. Inside shutters are known to have been used at the Capitol. Outside shutters are associated with buildings of wood frame and clapboard facing. How shutters are used is told by a contemporary who remarked "The shutters are always within the apartments wherever beauty is aimed at, those on the outside destroying the appearance of the front."*

The early form of blinds is characterized by narrow rails and stiles, and also by fixed slats. The width of rail of early measured examples is not greater than two inches. The thickness varies from 1-1/8" to 1-3/8". Stiles were finished with a small bead moulding. (See examples in Material Reference Files, Department of Architecture.)

Five pairs of blinds were provided for the Duke of Gloucester Street front and one pair at each end. There were no blinds attached to the north side of the house, none for the 4 light windows at the ends of the building.

The shutters or blinds, with their three raised panels, duplicate the design of shutters that exist on the Colonial frame house of Mr. H. D. Cole of Williamsburg. A pair of these was acquired by Williamsburg Restoration to serve as the model. The hardware for all shutters repeated the shape and attachment method of old wrought iron hardware of the H. D. Cole example. Wood for these was "heart yellow pine", joined by mortice, tenon and wood peg.

THE BLAIR HOUSE - ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION OF INTERIOR

(Block 22, Col. Lot 36)

Before considering the mechanical operations of "making over" inside the house, it will be well to take a general view of 18th century house interiors. The oldest houses of Williamsburg, when viewed from inside, gave indication of how the house was built. This was revealed by exposed framing beams, ceiling consisting of flooring boards of the upper story, and stairs starting from within the living room. It is probable that some early walls with brick "infilling" were only lightly plastered and so revealed the wall framing with texture and color. All of these features become concealed after about the middle of the 18th century. If the original Blair House ever exhibited such interior attractions, they must have vanished in process of frequent remodeling. Little is known of the old interior.

The operation of stripping walls aided, in establishing the location of some main partitions. However, evidence of panelling, cornices and chair rails was completely lost, excepting for the fragment of panelling in the living room, a relic of an early fireplace design.

Because so little of the interior was left unchanged, - in finishing the walls, no attempt was made to repeat the old lathing and plastering practices. Metal lath was adopted with its "firesafety" advantage. The "finish" coat to plastering was given a slight irregularity of surface, to suggest the surface of old work.

30Downstairs. - Wood flooring of the early 19th century was removed, thereby revealing underneath an old and typical pine floor. This under-floor was retained. Some patching was done and in places small areas were removed. The repair of flooring was done with use of floor boards from the "Restoration Warehouse" where buildings materials, salvaged from old buildings, are kept for this purpose. Here as elsewhere in Williamsburg, floors are of yellow pine, and in most instances are "rift-cut". Flooring of the 18th century in Williamsburg was usually a full inch in thickness or slightly more. The underside of flooring shows "rough sawing" while the top surface was planed smooth, probably on the job. Contemporary records report that "carpenters generally rough-plane the boards for flooring, before they begin anything else about a building, that they may set them to season . . . . ." Flooring was seasoned by standing the boards on end during construction of the house. They were frequently turned so as to equalize their drying. *

Flooring boards of the middle 18th century most commonly range in width around six inches or eight inches. Boards of ten, eleven and twelve inches broad and about 10 feet long are more usual early in the 18th century. Growing scarcity of large timber late in the century may account (in part) for the narrower flooring after 1750. You do not often find a mixture of 31 narrow and wide boards.

Oak flooring, harder in surface and more difficult to work was found in some barns and instances occur of oak floors for country churches. *

Upstairs. The same procedure as downstairs was carried out, namely removing late flooring and then repairing the old boards found in place.

STAIRS

The stairway in the "first" entrance hall toward the east end of the Blair House is largely original. Repairs had been made to the stairs from time to time. These minor changes consist of patches and removal of risers and treads, occasional replacement of old balusters by new ones and changes to molds of the string course.

The work done to put the stairs in usable and safe condition and return it, as closely as possible, to its original appearance can be summarized as follows:

- Parts of moldings to "closed" string course were "filled in" with moldings exactly the same as the original; using heart yellow pine and with same profiles. Contour for missing molds were determined by trace of profile made by repeated coats of paint against post and wall.

- 32

- New balusters were added to take the place of substitute "additions".

- The original newel post and handrailing needed only repairs and stiffening by resetting. No change was made to the balustrade detail, excepting that new newel post drops were added. In so doing, the design of the drops was made to conform with the same sort of detail found at the Wythe House, Williamsburg, and at Toddsbury, Gloucester County, Virginia.

The stairway at center of the house may be characterized as a "MIXED STAIRS"; that is, it has the straight run combined with some winders. It was a common type of stairs for the locality and period.

The stairway at rear, (west hall) is of secondary importance since it was an addition made some time after the building of the first part. The stairway details in their restoration appearance are entirely new. The size of the stairs however, was accurately defined by the framing of headers in the second floor joints. There were also sloping marks on the west wall to indicate the stringer and the starting place. Since the house was prepared so as to serve two families, it was decided to install the stairway, following details of the same date as the addition.

The stair run was built behind a new beaded board partition, having as a prototype, a similar stairway enclosure at 33 Blackstone, Virginia. It also has characteristics similar to a stairs in an outbuilding at Marmion, King George County, Va.

Wall stringers have a single beaded edge - using the Galt cottage precedent in Williamsburg. The nosing to the yellow pine treads repeats the same detail from the Brush House (Estelle Smith) on Palace Green.*

FIREPLACES

West Living Room - As previously mentioned in this report, the evidences of original paneling, chair railing and mantels had largely disappeared in process of "making over" at different times. A remnant of the old house was found in what is termed the original marble mantel in the living room, west end.** This was taken down, cleaned, repaired and then reset. The fireplace opening and the hearth were reconditioned making some use of brick from the "old brick" supply of the "Restoration". Hearth brick was laid in sand following 18th century practice. Brickwork for the fireplace itself was laid with oyster shell mortar.***

34Dining Room (East End) - The mantel for the dining room was from Surry County, obtained from a dealer. A notation was made in the restoration notes that woodwork details from Surry County resemble Colonial work of James City County. Care was exercised in making a selection suited to the period and details of the house.

The fireplace opening had been blocked up. By removing inner lining to the fireplace, the first fireplace chamber was found, cleaned and repaired. The hearth was also repaired, following the methods applied to other fireplaces.

Dining Room (Center)- The mantel detail followed the design of the dining room mantel at east end. It is, however, a reproduction, using same wood, same molds and was given the same finish.

The fireplace opening was stripped and repaired, also repairs were made to the hearth, following restoration practice as outlined above.

Second Floor Mantels - Bedrooms 13, 14 and 15 are new, designed by the Architectural Department, using as precedent, the second floor mantels at Belle Farm, Gloucester County, Va. All hearths are brick.

In the conditioning of all fireplaces for obvious reasons, flue tile was added and modem cast iron dampers installed.

COLOR

Eighteenth century color and with it "the use of paint" deserves a few remarks - applicable to this house.

During the operation of "conditioning" and "restoring" any house in Williamsburg, careful search is made for information on wall and woodwork finishes. Where paneling, doors or other wood details are obviously old, the surface is scraped with a sharpened instrument in order to reveal the layers of paint surface. The same is done for plastered walls. A record is kept of the colors found. New colors are recorded by exact matching. These are kept on file with similar colors kept together. This study and collecting of 18th century woodwork and wall color led to the setting up of standard shades and finishes. These representative colors may be examined in the Department of Architecture at any time. Their use in buildings is generally designated by number and finish.

The fashion of leaving interior wood in its natural color ended early in the 18th century and the complete room* was usually painted; the cornice was almost always painted to match the walls, and not whitened to correspond with the ceiling; the 36 former practice is obviously correct, since the walls and the cornice of a room, even today, is paralleled in its relation to the members of a classical column. The cornice, therefore, is a part of that column, and not a part of the building.

While most inside work was painted with lead and oil, it was common to white-lime plastered walls and ceilings. The whitewashing of walls (sometimes with color) became an annual operation attendant upon Spring house cleaning.* Hugh Jones in "The Present State of Virginia", 1721-24, pp. 25-26, describes houses in Williamsburg, "cased with feather-edges Plank, painted with white lead and oil . . . . . ."

Paint-color schedule for Blair House:

| Finish | Color | |

|---|---|---|

| Weatherboarding | White lead and oil. | White |

| Shutters | Lead and oil | Dark Green |

| Doors | ||

| Sash |

| Material | Color | Finish | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entrance Hall, #11 West | Wood | Sample 4 S | Egg shell gloss |

| Plaster walls | White | Like whitewash | |

| Wood baseboard | Black | Egg shell gloss |

| Material | Color | Finish | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living Room #9 (Middle) | Wood | Sample 313 | Semi-gloss |

| Plaster walls | White | Like whitewash | |

| Baseboard | Black | Semi-gloss | |

| Fireplace face | Black | Flat | |

| Entrance Hall #1 (East) | Same as second floor Hall #12 | ||

| Dining Room #2 (East) | Wood | Sample 311 | Semi-gloss |

| Plaster | White | Like whitewash | |

| Pantry #3 | Wood | Sample #42 (darker) | Like whitewash |

| Baseboard | Black | Enamel | |

| Kitchen #4 (East) | Same as pantry #3 | ||

| Dining Room #6 (Center) | Wood | Sample 133-S | Egg shell gloss |

| Plaster | A S | Flat | |

| Baseboard | Black | Egg shell gloss | |

| Fireplace face | Black | Flat | |

| Kitchen #7 (West) | Wood | Sample 133-S | Enamel |

| Plaster | #45 | Flat-washable | |

| Baseboard | Black | Enamel | |

| 38 | |||

| Rear Hall #10 (West) | Wood | Sample 171-S | Egg shell |

| Baseboard | Black | Egg shell gloss | |

| Plaster | Sample 4 S | Flat | |

| Material | Color | Finish | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bath #16 | Wood | Sample 4 S | Enamel |

| Plaster | Sample 21 W | Flat-washable | |

| Baseboard | Black | Enamel | |

| Bedroom #15> | Wood | Sample 21 W | Egg shell gloss |

| Plaster | Sample 4 S | Flat | |

| Baseboard | Black | Egg shell gloss | |

| Fireplace face | Black | Flat | |

| Bedroom #14 | Wood | White | Flat |

| Plaster | White #318 | Flat | |

| Baseboard | Black | Gloss | |

| Hall #12 | Wood | Sample 312 | Semi-gloss |

| Plaster | White | Like whitewash | |

| Baseboard | Black | Enamel | |

| Bath #17 | Wood | Sample 67-S | Enamel |

| Plaster | Sample 67-S | Egg shell | |

| Baseboard | Black | Enamel | |

| 39 | |||

| Bedroom #13 | Wood | White | Flat |

| Plaster | White #318 | Flat | |

| Baseboard | Black | Gloss | |

BASEMENT WINDOWS AND GRILLES

Basement windows were rather uniform in their design throughout the eighteenth century in Williamsburg. In many cases no glass was used for basement sash. Grilles were used as protection against invader. In the Blair basement there were no original frames but it was believed by inspectors at time of restoration that location of original openings was determined. The basement grilles found were scrapped and new ones, together with frames were installed. The design was based on examples of accepted authenticity, namely, McCandlick and Travis Houses.

The frames, stills and bars were made of heart-yellow-pine, fashioned in accordance with the methods practiced during the 18th century.

For comfort, glazed sash were inserted and hinges to rebates cut at the back of grilles. Sash muntins were so designed as to be concealed by the grille bars from exterior view.

THE BLAIR HOUSE - OUTBUILDINGS

Insurance Records of 1809 and the Frenchman's Map of C. 1786 offer meagre information on outbuildings. The Frenchman's Map shows a small, nearly square building, west of the house, believed to have been the "Blair Office". There are no outbuildings at the rear or within 100 feet east of the house. The absence of such lesser buildings, including the kitchen, is rather surprising and unaccountable. Getting down to the time when insurance records were made - near 1800, we have some additional information. The Insurance Record of 1809 - (#989) indicates existence of two buildings to the rear, near the east end of the house. The nearer one has the characteristics of a kitchen and is 18 feet from the house. To the rear of this building and around 60 feet from the house is a second building, approximately the same size as the supposed kitchen. The so-called "Blair Office" is shown 21 feet from the west end, its size is given as 24 feet wide by 16 feet deep. The testimony of Mr. Charles, an old resident of Williamsburg, seems to indicate what he terms a large building at the northern part of the plot. This may have been a late structure. The partial excavations undertaken as preparation for landscape planting discovered the well location and substantiated the buildings located on the Insurance Record.

The final decision of Architects and Advisors was to restore the kitchen and provide a yard with appropriate planting. Two new buildings to serve as garages were also built on the northeast and northwest corners of the plot. The outward appearance of the two 41 garages is "Colonial", adapted from a stable of the Van Garrett outbuilding group. The garages have double batten doors at gable ends. Walls are faced with flush random width boards, rough sawn. Windows consist of one 4-light, fixed sash in each garage. There is a door opening toward the yard as a supplement to the double garage doors. The cornice is unpretentious consisting of a crown mold and fascia. Mohawk asbestos shingles are used here as elsewhere as a substitute for original wood shingles. This use of asbestos shingles was determined by local fire safety code regulations.

The garage location and their design was carried out in conjunction with the location of a high board fence at the rear of property line. The eighteenth century appearance of the garage does not continue beyond its exterior. Within the carpentry, and finish followed 20th century building practice.

The hardware for swinging doors is 18th century in manner, created by craftsmen of the time of the restoration. The garages were whitewashed on both interior and outside.

The well-head was built over the original well, discovered when preparations were made for the landscape arrangement. It is just north of the central part of the house. The timber work is of heart yellow pine. The design was derived from the well head on Mrs. W. Christian's property on York Street, Williamsburg, and with some features suggested by a well head sketch made by Mr. W. S. Perry; the example from Falmouth, Virginia.

42A small hen house at the southeast corner of the yard was moved, repaired and rebuilt. This structure, was believed by A. A. Shurcliff, to be similar to Colonial poultry house examples. This and a second, repaired poultry house were whitewashed, reroofed and made to relate to the yard and garden.

Singleton P. Moorehead

March 22, 1945

Footnotes

An instance of clap-board roof is reported to have occurred in case of a "mid-eighteenth" century house owned by Orin Bullock.

THE JOHN BLAIR HOUSE INDEX

- BARGE boards

- 20

- Beams, exposed

- 29

- Belle Farm

- 34

- Blair, Archibald

- 3

- Blair House, Archibald

- 13

- Blair House, John

-

- Barge boards

- 20

- Beams

- 29

- Blair Office

- 16, 40

- Brick

- 24

- Ceiling

- 29

- Chair-railing

- 7,17,29, 33

- Chimney

- 10, 14, 23, 24

- Color

- 35

- Cornice

- Doors

- 12, 17, 25, 26

- Dormers

- 10, 18, 20

- Fireplace

- 33

- Floors

- 17, 30, 31

- House Plan

- 16

- Lean-to

- 9, 14

- Mantels

- 7, 33, 34

- Mortar

- 23

- Paint-color schedule

- 36-39

- Paneling

- 7,29,33

- Roof

- 14, 17, 18

- Shingles

- 17, 18

- Shutters

- 27

- Stair

- 16, 17, 31, 32, 33

- Steps

- 7

- Stonework

- 24

- Transom

- 26

- Walls

- 29, 35, 36

- Weatherboards

- 9, 10, 14, 35

- Window

- Woodwork, interior

- 12

- Blair, James

- 2

- Blair, John, Jr.

- 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 13

- Blair, John, Sr.

- 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 13

- Blair Office

- 16, 40

- Bond

- "Brick-pool"

- 10

- Brick, sizes

- 24

- Brush House

- 13, 33

- Bullock, Orin

- 18

- CAMPBELL, George

- 24

- Capitol

- 5, 27

- Ceiling

- 29

- Chair-railing

- 7, 17, 29, 33

- Charles, Mr.

- 40

- Chimney

- 10, 14, 23, 24

- Chiswell House

- 18

- Christian, W., Mrs.

- 41

- Clapboards

- 17,18,20

- Cole, H.D.

- 27

- College of William & Mary

- 2, 4, 7

- Color

- 35

- Corner boards

- 20

- Cornice

- DOOR-FRAMES, exterior

- 12

- Doors

- Door sills

- 12, 17

- Doorway

- 25, 26

- Dormers

- 10,18,20

- FACING boards

- 9

- Fireplace

- 33

- Floors

- 17, 30, 31

- Foundations

- 10

- Frenchman's Map

- 16, 40

- GALT Cottage

- 33

- Galt House, James

- 20

- HENING Statutes

- 13

- House Plan

- 16

- JONES, Hugh

- 36

- KIDD, Joseph

- 4

- LEAN-to

- 9, 14

- MANTELS

- 7, 33, 34

- Marmion

- 33

- McCandlick House

- 39

- Monroe, Mary

- 3

- Moorehead, Singleton P.

- 20

- Mortar

- 23

- Mutual Insurance Society of Virginia

- 10

- ORR'S Dwelling, Captain

- 20

- Orrell House

- 20

- PAINT-Color Schedule

- 36-39

- Paneling

- 7,29, 33

- Perry, W.S.

- 41

- RALEIGH TAVERN

- 4

- Randolph-Peachy House

- 18

- Reference

- 1

- Roof

- 14, 17, 18

- SASH

- 21

- Sheathing boards

- 17

- Shingles

- 17, 18

- Asbestos

- 18

- Shurcliff, A.A.

- 42

- Shutters

- 27

- Stair

- 17, 31

- Stairway

- 16

- Steps

- 9

- Stonework

- 9, 24, 33

- Swem, E. G.

- 7

- TRANSOM

- 26

- Travis House

- 39

- Tyler, L. G.

- 5, 14, 24

- VAN GARRETT

- 41

- WALLS

- 29, 35, 36

- Weatherboards

- 9, 10, 14, 35

- William & Mary Quarterly

- 5

- Window

- Woodwork, interior

- 12

- Wythe House

- 32

THE TWO JOHN BLAIRS - PATRIOTS AND STATESMEN

From deeds relating to the Brush-Everard property it is apparent that John Blair, the elder, possessed lots #165 and #166 after 1745. It is possible that he purchased them on February 14, 1751, on the day when, according to a note in his famous diary, he attended "Mrs. Dering's outcry" or public auction of the property. It is not known how long he held the lots but he died in 1771, and a John Blair -- his son it must have been -- transferred lot #172, the lot on which the garden was located, which lay directly east of those on which the former Brush house stood, to Thomas Everard in 1773. We know that by 1779 Everard was also in possession of lots #165 and #166. To our knowledge neither the elder nor the younger Blair ever occupied the house.

Both Blairs were illustrious men. John Blair, the elder, was born in Virginia in 1687, the son of Archibald Blair, whose brother, the famous (and contentious!) Dr. James Blair, was instrumental in the founding of the College of William and Mary. John Blair became president of the Council and was three times acting governor of the colony -- twice in the interim between the departure of a governor for England and the arrival of his successor, and the third time upon the death of Lord Botetourt in 1770. He held the high office on this occasion for a short time only, resigning on account of old age and infirmities. He died in Williamsburg in 1771.

The diary of John Blair, Sr., jotted down on a calendar for the year 1751, has been the source of much valuable information about Williamsburg, and in particular about the rebuilding of the Capitol after it had burned in 1748. Judging by his frequent references to the progress of the work, Blair, always interested in building projects, large and small, probably had charge of the Capitol's reconstruction, and also, possibly, of its original erection, for he writes on December 12:

"This afternoon I laid the last top brick of the Capitol wall, and so it is now ready to receive the roof, and some of the wall plates were rais'd and laid on this day. I had laid a foundation brick at the first building of the Capitol above 50 years ago, and another foundation brick in April last, the first in mortar towards the rebuilding, and now the last as above."

John Blair, Jr., no less distinguished than his father, was born at Williamsburg in 1732, studied law at the Temple in London and commenced his practice in Williamsburg. He was several times a member of the House of Burgesses as representative of the College, and also served as clerk of the Council.

In the troubles which led to the Revolution the elder Blair, despite the high offices he had held under the Crown, had always been on the popular side. His son followed in his footsteps. John Blair, Jr. for example, was a member of the Committee which in June 1776, reported the declaration of rights and the state constitution. Upon establishment of the Virginia judiciary he was elected judge of the general court and later became chief justice. He was a member of the convention in Philadelphia in 1787 which framed the Federal constitution, voting for its adoption, and subsequently for its ratification in the state convention of 1788. He was appointed by Washington associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and held his seat until 1796, when resigned. He died in Williamsburg on August 31, 1800.

H.D.—Dec. 9, 1949.