Anderson Blacksmith Shop Architectural Report, Block 10 Building 22F Lot 18 Originally entitled: "Report on Proposed Reconstruction of James Anderson Forges, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1230

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

REPORT

ON

PROPOSED RECONSTRUCTION OF JAMES ANDERSON FORGES,

COLONIAL WILLIAMSBURG FOUNDATION

Box 7357

Richmond, Virginia

23221

CONTENTS

| Text | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| The Proposed Building | 2 |

| Structure | 4 |

| Exterior treatment | 5 |

| Interior treatment | 7 |

| Fenestration | 8 |

| Doors | 10 |

| Fittings | 11 |

| List of Precedents | 12 |

| Notes | 13 |

| Appendix | 15 |

| Bibliography | 17 |

| Captions to photographs | 19 |

INTRODUCTION

According to Program Planning Committee minutes, the James Anderson forge project is intended to "show the changes in one-man craft shop techniques to the sophisticated development prior to the industrial revolution and that products were not made totally by one person as was usually assumed, but as a joint effort by several persons." It is further intended to emphasize the volume of production made possible by specialization, to "disabuse visitors of the stereotyped image of the traditional craftsman as a jack-of-all-trades," and to offer a glimpse of 18th-century building techniques. The purpose of this report is to interpret the drawings submitted for the building in the light of the latter goal.

For logistical purposes, it was determined before the research project was undertaken that forge A-1 will be the primary operating unit, and will be a 12-month operation. Forges A-2 and C will operate seasonally, and forge A-3 will be used for preliminary interpretation.1A-1 & A-2 are now primary [illegible] is now secondary. A-3 is same A satisfactory circulation pattern and a comfortable environment for the year-round forge are therefore essential. I believe that the drawings which accompany this report should suit that end, as well as the interpretive aims.

THE PROPOSED BUILDING

During the 17th century in the Chesapeake region, social instability, economic inability, and labor constraints combined to reshape the building traditions imported by the region's European immigrants. These changes were of two kinds. First, the building system itself was recast into a form that, though it had demonstrable connections with English forms, was distinctive and not closely related to any particular local English tradition. Second, a repertory of temporary, cheap and otherwise labor-conservative devices, some traditional and some novel, was accumulated. 2

Although disparate rates of survival have tended to obscure the diversity of 18th-century building practices, occasional survivals and the evidence of documents give an impression of the great variety of structural quality and finishes surviving from the 17th century into 18th-century Chesapeake building (figures 1, 2). In work buildings alone, one can cite examples ranging from the (typically) carefully and heavily framed, but undecorated grist mills like the one at Ivy, Albemarle County, Virginia, through Jarves Spencer's cooper's shop, described in the 1780s as being "17 feet by 14 shingled roof [,] sides and ends enclosed with slabs framed on posts in the ground, in middling repair . . ."3 Between these extremes there were a number of alternatives to the neatly framed buildings with beaded weatherboards and round-butted shingles that we associate with Revolutionary-era -3- Virginia. These normally involved the use of relatively substantial major frames, with shortcuts taken in the manufacture and joinery of the secondary elements.

For the James Anderson shop, the drawings include several alternate techniques that are intended to suggest this range of possibilities available to the 18th-century builder. The parameters of the building were set by the archaeological excavations, which revealed a structure 93 feet long, built in several stages in the 1770s. The brick underpinnings, the relative chronology of the sections, the location of the individual forges and the probable location of the anvils, and the brick paving in the original section--shop A-1--are all documented by archaeology, with the underpinnings and the forges documented as well in Humphrey Harwood's account books.4

Other questions about the Anderson forge were not answered by archaeology or documents. The size and location of the openings, the presence or absence of the south wall of shop A-1 after the construction of shop A-2 and, most of all, the exact nature of the structure and its finish were not accessible from these sources.

The complicated history of the building and its site, combined with the lack of historical specificity at several key points, allows the use of contrasting structural techniques within the building to be erected. In addition, there will be a contrast in the appearance of the forge and that of the other, more elaborate structures in the museum area. In both cases, extensive opportunities for interpreting the 18th-century architecture of Virginia will be available. -4- Indeed, it is likely that the contrasts within and without the Anderson forge will be so striking to visitors that they will initiate discussions of the building's architecture.

Structure

The archaeological findings show that, while this was certainly not as elaborate a structure as any of the nearby houses, neither was it as poorly constructed as Spencer's cooper's shop, cited above. The cheapest sort of building--holeset posts with a dirt floor--was not present here, for the archaeologists found evidence of brick underpinnings in all parts of the building. Consequently, some sort of frame building set on underpinned sills is called for. However, intermediate forms of cost- and labor-cutting devices alluded to above have been incorporated in the design of the Anderson forges.

The Chesapeake framing tradition offers a fairly narrow range of variation in the basic structure, and the frame indicated in the drawings is the customary Chesapeake one, in terms of structural system joinery, and scantling. One small variation is found in the relationship of joist and plate in shop C, where the two are half-lappedNot [illegible], dropping the joists down flush with the wall plate, and sealing the eaves. [1] 5

In the details of the secondary members, the principle to bear in mind is the concern for labor economy. While the basic frame is a solid one, shortcuts are taken where strength is not a factor. The studs in all of the shops are unbarked poles, flattened slightly -5- only on those faces where a cladding is to be fastened. [II] (Figs. 1, 3, 4) They are cut at an angle at the top and bottom (except shop A-1, where they are tenoned at the bottom), and nailed into a responding beveled mortise cut into the plates, girts, and sills. This is a common device throughout Anglo-America. A Virginia example, to cite just one, is the mid-18th-century kitchen at Marmion, King George County, where all of the studs were attached in this manner. (See also fig. 15.)

All sections of the roof will be framed with simple common-rafter-and-collar trusses, set on board false plates. Since shop A-1 is conceived of as the original building, and the others as additions made in the heat of wartime production (and hence somewhat less well built), its rafters will be sawn and joined in the standard Virginia manner, with an open-faced mortise-and-tenon joint, and a peg, at the apex. Shops A-2, A-3, and C will be riven from radial sections of an unsquared log. Only the end rafters of these three roof sections will be squared (by adze), and all of the rafter couples will be half-lapped and nailed. The collars will also be riven, and set into shallow recesses on the sides of the rafters, and nailed in place. [III] A few horizontalsteadying laths nailed to the undersides of the rafters during erection can be left in place. [III] (Figures 5, 6)

All major framing members, except as indicated, will be hewn and adzed.

Exterior Treatment

As indicated in the drawings, the walls and roof of all sections of the shop will be covered with riven clapboards, in lengths -6- of ±4 feetdrawn as 6 "Bds w/4" exp. Underhill says exa will vary with Bd width, 4-5 inches to the weather. On the roof, they will be combed at the ridge, and will project just enough beyond the gables to seal the wall--about ½ to 1 inch. They should also project beyond the feet of the rafters about 2- ½ to 3 inches. There will be no cornice treatment beyond the visible joist ends. [III, VIII, IX] (Figure 11). The clapboards should be feather edged and lapped at the ends. The joints will all break at the same rafters. Precedent for this is the standard practice of all surviving Virginia clapboard roofs.6 Examples of the individual features are illustrated in Figs. 5-11.

The wall clapboards should be constructed and applied in the same manner, with the clapboards on the long sides projecting about ¾ inch to 1 inch beyond the gable end, to seal the end clapboards. On shop A-1, the joints will break on alternate studs as indicated. On all of the other shops, the joints will break in a line, as on the roof. [V] However, on the gable ends it is not necessary that one joint run the entire height of the building. The lines can shift from one stud to another occasionally. (See east northelevation drawing.) The clapboards should extend from the lower edge of the sill to the upper edgenot possible or desirable of the wall plate.

The roof should be coated with black tar [III, IV, VI], as should the gables. [III, VII] Documentary evidence supports the physical documentation of tarring. To cite one example the vestry Of St. Peter's parish in 1708 ordered the construction of a glebe house "To be weatherboarded with featheredge Plank [clapboard], & Gable ended, & Covered [on the roof] wth: Plank & shingled wth: Cypress shingles, ye: [roof] Covering & weatherboards to be Tarr'd." 7

At the Anderson forge, the vertical walls except the gables -7- will be whitewashed. [III] (Figures 12, 13, 14). This combination of tarred roof and gables and whitewashed walls, directly taken from the Ball-Sellers house, Arlington County, Va., represents a vernacular aesthetic quite different from that embodied in most of the Colonial Williamsburg buildings, and should provide lively interpretive opportunities.

Interior Treatment

There is no archaeological evidence of the shops' ever having been lathed and plastered, although Humphrey Harwood billed Anderson £9.9s "To 250 Lathes @ 1/6 & Lathing & plasterg Room to Shop 6/" in 1787. 8 Because of the late date and unspecific nature of this entry, I believe that it should be passed over. 9

The interior, then, will be as strikingly finished as the exterior. The walls of shops A-1 and A-2 will be covered, again, with riven clapboards to the height of the joist soffits. Again, the joints will be unbroken and the surfaces whitewashed. The clapboards should be carried to just below the top of the sill.not possible [X, XI]. (Figure 15.)

There will be no interior wall finish in shops A-3 and C.

Floors: Shop A-1 will have a brick floor, as indicated by the archaeology. Shops A-2, A-3, and C will have dirt floors. In the lofts, shops A-1 and A-2 will have a plank floor laid at joist level. It will be accessible by a ladder-stair in shop A-2, with framing for a stairwell in the ceiling of shop A-1 indicating that -8- there was originally a stair there which was removed when the one in shop A-2 was installed. Shop A-3 will have a lapped clapboard loftomitted at design [illegible] committee meeting laid on the collars, and accessible by a ladder. [XII] Shop C will be open to the roof. [I]

Other details: The wall between shops A-1 and A-2 will be illustrated as torn out as far as the feet of the braces on either corner. This will necessitate making the empty bevels, with nails or nail-holes in them, in the joist at this point. The clapboards will have been stripped off in the missing section and, since the joints of the clapboards are broken on the exterior of shop A-1, they will of necessity expose some of the framing of the remaining wall, as well as the feathered ends of the remaining clapboards.* Again, an opportunity exists for the interpretation of the building's peculiar structural features.

The gable end of shop A-1 that shows in shop A-3 should be treated as a formerly exposed exterior wall, as should the portion of shop A-2 that shows in shop C.

Fenestration

The fenestration has been the most difficult problem to solve. The overwhelming pictorial evidence is for unglazed windows, and very large ones at that. Most of the pictorial material, from the 16th century German engraving Der Schmidt to the early 19th-century American painting Pat Lyon at the Forge, shows no window closure of any kind. (Figures 17, 18, 19.) There are two exceptions. A mid-18th-century engraving for the frontispiece of The Loyal Blacksmith of Marlborough (London, 1744) shows a high, leaded glass window with -9- diamond panes. (Figure 21). It is impossible to tell whether it was a fixed or casement sash. A modern photograph of the 16th- or 17th-century blacksmith shop at Claverdon, Warwickshire, England, shows a building with two large, square openings set next to each other. (Figure 20). These may be alterations to the original building. One has a fixed, six-light sash,the glass panes are [illegible] apparently of 18th- or early l9th century date, and the other is unglazed. Both are fitted with exterior wooden shutters of late construction.

The need for a comfortable working environment and for controlled lighting expressed by Colonial Williamsburg's blacksmith, and the security needs of the museum, have led me to employ a variety of window arrangements that reflect recorded Chesapeake practice, while drawing on the license offered by the illustrations, notably the ones from the Loyal Blacksmith and Claverdon. The latter is the precedent for the double sash lighting the work bench in shop A-1. The rear windows on that shop have squarish sash which slide into the walls. These are based on the sashless frame of a similar window found in the north wall of the original section of Linden Farm, Richmond County. 10 [VII] (Figure 23). Similar arrangements were found at an early 19th-century house in Northampton County, Virginia, where the sash were of the approximate size of those I have drawn, and at the Marshy Point House, Kent County, Maryland, where unglazed openings 8" wide by 3'0" high, and 12" by 3'0" were closed by sliding shutters on an interior track. Similar sash, hinged as inswinging casementschgd. to removable sash, will be used on shop A-2, while fixed- changed to [illegible] sliding shutters [illegible] sash will be employed on shop A-3. Shop C will have inswinging chg. to vert sliding sash (east) & 2 vert. sliding shutters (west)wooden shutters, modeled after those at Epping Forest, Lancaster County. [IV] (Figure 24).

-10-Except for the wooden shutters, all of the windows will be glazed, but with repairs made with paper and twine as a wartime expediency. This is documented for the Anderson forge in several places in the accounts of the public stores, e.g., "To five quire paper to repare windows" on December 7, 1778. The twine is suggested by a similar entry for February 2, 1779, "To 5 quire paper @ 7/ to repare the windows of the house rented of Mrs Hay ½ # Twine." 11 The interpretation is supported by an observation of Benjamin Henry Latrobe's made during his sojourn in Virginia in the mid-1790s.

In Amelia I could have again fancied myself in a society of English Country Gentlemen . . . had not the shabbiness of the mansions undeceived me. Of the latter I do not mean to speak disrespectfully. It is a necessary consequence of the remoteness of the country [from places] where workmen assemble & can at all times be had. An unlucky boy breaks two or three squares of glass. The glazier lives fifty miles off. An old newspaper supplies their place in the mean time. Before the mean time is over the family gets used to the newspapers & think no more of the glazier.12

Doors

All of the doors are vertical-boarded doors with horizontal interior battens, a standard 18th-century Virginia form. (Figure 27). The door from A-1 to A-3, which would originallyChg'd to second period (as an [illegible] is now an interior door have been an exterior door, is a slightly better made one, with exterior vertical battens nailed over the joints. [1] (Figures 28, 29). The pattern of door openings, with large four-foot doors creating aisles between the forges in shop A-2, and with the doors throughout the building opening between the forges, is based on the plan of Thomas Jefferson's nailery of 1794 at Monticello. 13 The use of windowless, all-door facades is supported -11- by many illustrations of 18th- and l9th-century blacksmith's shops, such as the English shop illustrated-by Birket Foster.19th Cent. shop (Figure 22). Foster's illustration also illustrates a shop with large, full-height doors, as does the photograph of the Claverdon shop. (Figure 20). Similar doors are illustrated in a photograph of a 19th-century wheelwright's shop in Mecklenburg County, Virginia. 14

Fittings

All of the doors will be hung on iron hinges. The double doors should be hung on three pairsWG says 2 prs.? of long strap hinges mounted on pintels, and should be closed by a simple hasp.[illegible] bar & iron keepers The smaller doors should be hung on cross-garnet hinges. [XI] (Figures 15, 25). Simple latches can be used on the other exterior doors, while the interior doors and the wooden shutters should have wooden latches, as illustrated. 15 [IV, XI] (Figures 15, 24, 26). The interior shutters omittedcan be hung on either cross-garnet or strap hinges. (Figure 24).

LIST OF PRECEDENTS

| I | Kitchen (late 18th c.), Turner House, Isle of Wight County, Va. |

| II | Park Gate (4th qtr 18th c.), Prince William County, Va. |

| III | Ball-Sellers House (3rd qtr 18th c.), Arlington County, Va. |

| IV | Laundry (late 18th c.), Epping Forest, Lancaster County, Va. |

| V | Maxwell Hall Barn (late 18th c.?), Charles County, Md. |

| VI | Kempsville [Dragon Ordinary] (3d qtr 18th c.), Gloucester County, Va. |

| VII | Early sections, Linden Farm (early to mid-18th c.), Richmond County, Va. |

| VIII | Glen Cairn (2d qtr 18th c.; 4th qtr 18th c.), Essex County, Va. |

| IX | Original section, Maynard house (4th qtr 18th c.), Surry County, Va. |

| X | Partitions, Dependencies, Mulberry Fields (3d qtr 18th c.), St. Mary's County, Md. |

| XI | Cellar partitions, Bowling Green Farm [Old Mansion] (3d qtr 18th 0.), Bowling Green, Caroline County, Va. |

| XII | Attic, Cloverfields (2d qtr 18th c.), Queen Anne's County, Md. |

NOTES

APPENDIX

A 19th-Century Blacksmith Shop

(The following excerpts from the diary of Richard Eppes, kept at Appomattox Manor, City Point, Prince George County [now Hopewell] are of interest for the light they throw on the construction and furnishing of blacksmith shops. Eppes was constructing a shop at his Bermuda Hundred plantation. Note how quickly it was erected. The speed is probably a rough indicator of the quality of the building.)

(p. 133, June 12, 1856)Had timber carried over to Bermuda to build a Blacksmith shop Jeff carpenter [a hired slave] commenced work today on it Spot selected for shop by the drawbars. Made arrangements with Mabry to run the chimney tomorrow or Saturday. price not agreed upon.(p. 134, June 13, 1856)

Visited Petersburg this morning taking Solomon Blacksmith with me . . . .Outfit of Blacksmith Shop Dunn & Spenser. Cost $65.03

$ ? 1 Extra bellows 34 inch 15.00 1 Extra Anvil 170 lbs (11? per lb) 18.70 1 Extra vise 65 lb 1/ 10.83 1 Beak Iron 40 lb 9s 5.00 2 Hand Hammers 8 9s 1.00 1 Stoks & Dec en 300 450 7.50 1 Buttress .88 1 Farmers Hammer .75 -16- 1 Drill 3.00 1 pr Pincers .37 1/3 g files 2 Rasps 750 2.50 the above bill was bought & paid for of Dunn & Spenser of Petersburg. In addition I had two large Sledge hammers before & have purchased aprons since iron & steel

Mabry crossed over to commence chimney to shop. I having borrowed 900 bricks from Alfred James with a promise to return them soon price not fixed for chimney [sic].

(p. 135, June 14, 1856) Crossed to Bermuda this morning, found Jef has framed and commenced planking Bl. Shop, also Mabry had commenced the chimney. both expected to finish today.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

- Anderson, James. Account Book, 1788-99. MS., Virginia Historical Society, Richmond.

- Bealer, Alex W. The Art of Blacksmithing. Rev. ed. New York: Funk and Wagnalls, 1976.

- Bruce, Kathleen. The Manufacture of Ordnance in Virginia During the American Revolution. Washington: Army Ordnance Association, 1927.

- ---------------, Virginia Iron Manufacture in the Slave Era. New York: Century Co., 1931.

- Carson, Cary, Norman F. Barka, William M. Kelso, Garry W. Stone and Dell Upton. "Impermanent Architecture in the Southern Colonies," Winterthur Portfolio, 1981 in press.

- Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. The Blacksmith in Eighteenth-Century Williamsburg: An Account of His Life and Times and of His Craft. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1971.

- Dunshee, Kenneth. The Village Blacksmith. Watkins Glen: Century House, 1957.

- Foss, Robert. Report on the 1975 Archaeological Excavations at the James Anderson House. MS., Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1977.

- Hatch, Charles E., Jr., and Thurlow Gates Gregory. "The First American Blast Furnace, 1619-1622: The Birth of a Mighty Industry on Falling Creek in Virginia," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, 70 (1962): 259-96.

- Harwood, Humphrey. Account Books, Ledgers B, C, D. Microfilm, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Jefferson, Thomas. Thomas Jefferson's Farm Book. Ed. Edwin Morris Betts. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953.

- Land by the Roanoke: An Album of Mecklenburg County, Virginia. N.p.: Roanoke River Branch, APVA, 1957.

- Queen Annes County, Md. Orphans Court Records. MS., Hall of Records, Annapolis, Md.

- Ross, David. Letterbook, 1812-1813. MS., Virginia Historical Society. -18-

- Upton, Dell. "Board Roofing in Tidewater Virginia," APT Bulletin, 8 (1976): 22-43.

- ----------- "Traditional Timber Framing: An Interpretive Essay," in The Material Culture of the Wooden Age, ed. Brooke Hindle. Tarrytown, NY: Sleepy Hollow Press, 1981 in press.

- Virginia Historic Landmarks Commission. Survey files, 1967-1981. Richmond.

- Watson, Aldren A. The Village Blacksmith. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1968.

- Webber, Ronald. The Village Blacksmith. South Brunswick: Great Albion Books, 1972.

CAPTIONS

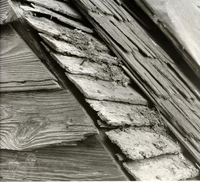

Fig. 1. Park Gate (76-18), Prince William County, Va. 4th qtr 18th c. Roof structure showing studs attached in makeshift manner, poles used for studs (e.g., over door). (Photo: Fraser D. Neiman for Virginia Historical Landmarks Commission [VHLCI, 1976)

Fig. 1. Park Gate (76-18), Prince William County, Va. 4th qtr 18th c. Roof structure showing studs attached in makeshift manner, poles used for studs (e.g., over door). (Photo: Fraser D. Neiman for Virginia Historical Landmarks Commission [VHLCI, 1976)

Fig. 2. Ball-Sellers house (00-9), Arlington County, Va. 3d qtr 18th c. Exposed joist, crudely hewn. This and the previous figure illustrate some of the improvisatory framing techniques to be found in 18th-century Virginia houses. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 2. Ball-Sellers house (00-9), Arlington County, Va. 3d qtr 18th c. Exposed joist, crudely hewn. This and the previous figure illustrate some of the improvisatory framing techniques to be found in 18th-century Virginia houses. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 3. Park Gate. Parlor, showing rough studs, including unbarked pole in right foreground. (Fraser D. Neiman for VHLC, 1976)

Fig. 3. Park Gate. Parlor, showing rough studs, including unbarked pole in right foreground. (Fraser D. Neiman for VHLC, 1976)

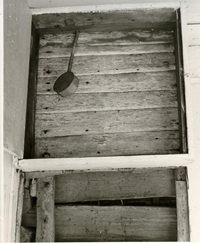

Fig. 4. Park Gate. Loft framing, showing crude attachment of studs, pole studs. (Fraser D. Neiman for VHLC, 1976)

Fig. 4. Park Gate. Loft framing, showing crude attachment of studs, pole studs. (Fraser D. Neiman for VHLC, 1976)

Fig. 5. Ball-Sellers house. Loft. Note riven rafters and collars, lath to steady rafters nailed to underside of rafters at right, clapboard roof and gables, whitewashed interior. The dark weatherboards are the gable end of the adjacent structure. (Dell Upton, 1976)

Fig. 5. Ball-Sellers house. Loft. Note riven rafters and collars, lath to steady rafters nailed to underside of rafters at right, clapboard roof and gables, whitewashed interior. The dark weatherboards are the gable end of the adjacent structure. (Dell Upton, 1976)

Fig. 6. Ball-Sellers house. Underside of roof. Note riven, quartered rafters, steadying lath, feathered ends of clapboards, even vertical joint of clapboards. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 6. Ball-Sellers house. Underside of roof. Note riven, quartered rafters, steadying lath, feathered ends of clapboards, even vertical joint of clapboards. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 7. Epping Forest Laundry (51-8), Lancaster County, Va. Late 18th c. Illustrating original clapboard roof. Note amount of original lap from course to course, slight projection of clapboards beyond gable to seal tops of weatherboards. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 7. Epping Forest Laundry (51-8), Lancaster County, Va. Late 18th c. Illustrating original clapboard roof. Note amount of original lap from course to course, slight projection of clapboards beyond gable to seal tops of weatherboards. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 8. Epping Forest laundry. Note width of clapboard exposure to weather, remnants of tarring. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 8. Epping Forest laundry. Note width of clapboard exposure to weather, remnants of tarring. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 9. Epping Forest laundry. Interior of clapboard roof. Note feathered ends of clapboards, straight vertical joint projecting slightly beyond rafter. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 9. Epping Forest laundry. Interior of clapboard roof. Note feathered ends of clapboards, straight vertical joint projecting slightly beyond rafter. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 10. Ball-Sellers house. Exterior of original clapboard roof. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 10. Ball-Sellers house. Exterior of original clapboard roof. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 11. Ball-Sellers house. Exterior of clapboard roof at eaves. Note exposed joint ends, irregular shaping of joists (cf. fig. 2). (Joseph F. Yates for VHLC, 1977)

Fig. 11. Ball-Sellers house. Exterior of clapboard roof at eaves. Note exposed joint ends, irregular shaping of joists (cf. fig. 2). (Joseph F. Yates for VHLC, 1977)

Fig. 12. Ball-Sellers house. Clapboarded exterior wall. Note amount of exposure to weather of each course, relatively even edges, whitewashed surface. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 12. Ball-Sellers house. Clapboarded exterior wall. Note amount of exposure to weather of each course, relatively even edges, whitewashed surface. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 13. Ball-Sellers house. Detail of preceding. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 13. Ball-Sellers house. Detail of preceding. (Dell Upton, 1977)

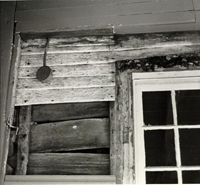

Fig. 14. Ball-Sellers house. Exterior clapboarding. Note clapboard trimmed for early window frame. (Joseph F. Yates for VHLC, 1977)

Fig. 14. Ball-Sellers house. Exterior clapboarding. Note clapboard trimmed for early window frame. (Joseph F. Yates for VHLC, 1977)

Fig. 15. Bowling Green Farm (171-4), Bowling Green, Caroline County, Va. Mid-18th c. Clapboard partition in basement. Note unbroken joints, even edges of courses, lap bevel joints at base of studs, sill resting directly on the earth, whitewashed finish. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 15. Bowling Green Farm (171-4), Bowling Green, Caroline County, Va. Mid-18th c. Clapboard partition in basement. Note unbroken joints, even edges of courses, lap bevel joints at base of studs, sill resting directly on the earth, whitewashed finish. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 16. Ball-Sellers house. Interior treatment of eaves, where clay is packed at base of board roof, whitewashed. (Dell Upton, 1976)

Fig. 16. Ball-Sellers house. Interior treatment of eaves, where clay is packed at base of board roof, whitewashed. (Dell Upton, 1976)

Fig. 17. Jost Amman, Der Schmidt (16th c.). (From Ronald Webber, The Village Blacksmith)

Fig. 17. Jost Amman, Der Schmidt (16th c.). (From Ronald Webber, The Village Blacksmith)

Fig. 18. Blacksmith (16th c.). (from Webber)

Fig. 18. Blacksmith (16th c.). (from Webber)

Fig. 19. John Neagle, Pat Lyon at the Forge (early 19th c.) (Museum of Fine Arts. Boston)

Fig. 19. John Neagle, Pat Lyon at the Forge (early 19th c.) (Museum of Fine Arts. Boston)

Fig. 20. Blacksmith shop (16th or 17th c.), Claverdon, Warwickshire, England. The tandem windows are one precedent for those on the front of shop A-1. (from Webber)

Fig. 20. Blacksmith shop (16th or 17th c.), Claverdon, Warwickshire, England. The tandem windows are one precedent for those on the front of shop A-1. (from Webber)

Fig. 21. The Loyal Blacksmith of Marlborough (London, 1744). (from Webber)

Fig. 21. The Loyal Blacksmith of Marlborough (London, 1744). (from Webber)

Fig. 22. Birket Foster, l9th-century smithy. Note the windowless, all-door facade. (from Webber)

Fig. 22. Birket Foster, l9th-century smithy. Note the windowless, all-door facade. (from Webber)

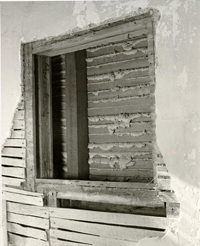

Fig. 23. Linden Farm (79-10), Richmond County, Va. Early to mid-18th c. Original window frame in north wall made to accommodate a single sash that slid left into the wall. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 23. Linden Farm (79-10), Richmond County, Va. Early to mid-18th c. Original window frame in north wall made to accommodate a single sash that slid left into the wall. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 24. Epping Forest Laundry. Gable-end shutter with strap hinge, battens, and wooden latch. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 24. Epping Forest Laundry. Gable-end shutter with strap hinge, battens, and wooden latch. (Dell Upton, 1975)

Fig. 25. Bowling Green Farm. Cross-garnet hinge, cellar door. See figs. 15, 26. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 25. Bowling Green Farm. Cross-garnet hinge, cellar door. See figs. 15, 26. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 26. Bowling Green Farm. Wooden latch, cellar door. See figs. 15, 25. (Dell Upton, 1977)

Fig. 26. Bowling Green Farm. Wooden latch, cellar door. See figs. 15, 25. (Dell Upton, 1977)

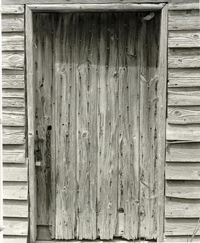

Fig. 27. Epping Forest smokehouse (51-8), Lancaster County, Va. Early 19th c. Vertical-board door. (Bernard L. Herman for VHLC, 1975)

Fig. 27. Epping Forest smokehouse (51-8), Lancaster County, Va. Early 19th c. Vertical-board door. (Bernard L. Herman for VHLC, 1975)

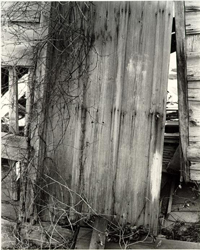

Fig. 28. Turner house kitchen (46-33), Isle of Wight County, Va. Late 18th c. Vertical-board-and-batten door. (Dell Upton, 1981)

Fig. 28. Turner house kitchen (46-33), Isle of Wight County, Va. Late 18th c. Vertical-board-and-batten door. (Dell Upton, 1981)

Fig. 29. Turner house kitchen. Detail of fig. 28. (Dell Upton, 1981)

Fig. 29. Turner house kitchen. Detail of fig. 28. (Dell Upton, 1981)