Robert Nicolson House Architectural Report, Block 7 Building 12Originally entitled: "The Robert Nicolson House, Block 7, Building 12; A Social and Architectural Study"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1084

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

The Robert Nicolson House

Block 7, Building 12:

A Social and Architectural Study

Department of Architectural Research

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

1986

CONTENTS

| Introduction | |

| Chapter I | |

| Social Profile of Robert Nicolson | 2 |

| Chapter II | |

| Physical Analysis | |

| A. Exterior | 12 |

| B. Interior | 18 |

| C. Chronological Summary | 55 |

| Chapter III | |

| Interpretive Issues | |

| A. The Side-passage Plan | 53 |

| B. The Extension | 61 |

| C. Front vs. Rear | 67 |

| D. Geometry | 70 |

| Illustrations | |

| Plans |

INTRODUCTION

This report documents the physical history of the Robert Nicolson House and explores its significance from a social perspective. The first chapter deals with Robert Nicolson's rise to respectability as a successful tradesman and discusses the manner in which his material possessions (including the house) reflected this process.

The second chapter is strictly descriptive, being primarily a room-by-room account of the dwelling's physical development, differentiating where possible between original and altered or replaced features. Owing to a harried schedule of construction in 1981, it was necessary to base this account primarily on superficial visual inspection. Following this discussion is a chronological summary of changes made to the house since its completion early in the 1750s.

The last chapter seeks to identify the significant interpretative issues concerning Robert Nicolson's dwelling, formulating answers to the questions they raise. Together, these three sections should create a new understanding of the Nicolson House, based on a more intimate knowledge of the structure and the man whose aspirations and successes it embodied.

I. SOCIAL PROFILE OF ROBERT NICOLSON

Although the greater portion of Robert Nicolson's adult life here in Williamsburg is well documented, his early background remains rather obscure. By 1749, when records first reveal his presence in Williamsburg, he was 24 years of age, a tailor by trade. His wife Mary, 27 years of age, had just given birth to a son, William, perhaps their first child.1 Records from this period suggest that Nicolson had already met with modest success. An early account with Alexander Craig, reveals that he owned at least one horse and had a male servant at his disposal.2 Entries in the Virginia Gazette daybooks for the year 1751 reveal that he was advertising in the Williamsburg paper, no doubt publicizing his services as a tailor.3

In May of that year, Nicolson purchased a lot in the new suburb that Benjamin Waller had recently laid out east of the Capitol.4 His ownership of a lot in this part of town is of 4 particular interest since several other tradesmen had already moved into the area. Stephen Brown, a butcher, owned lots 35 and 36. Bricklayer Samuel Spurr appears to have owned lot 27, and lot 25 had been purchased by Alexander Craig, the saddler and harness maker. Nicolson bought lot 26 between Craig and Spurr from a cabinetmaker named James Spiers. Shortly afterward, additional lots in the area were purchased by still other tradesmen. In February of 1752, housecarpenter Christopher Ford bought an unspecified parcel of property in the area and seven months later, wheelwright (later housecarpenter) Benjamin Powell purchased lot #30. Not quite a year afterward, John Stretch, the printer, bought lots 21 and 22. Throughout the 1750s, Benjamin Powell and Samuel Spurr continued to acquire additional property in the Waller suburb.5 The area thus became an enclave of upwardly mobile tradesmen who had accumulated sufficient funds to purchase a lot and build a house.

Like all conveyances of lots in the Waller suburb, Robert Nicolson's deed stipulated that the purchaser build "one good Dwelling House" 16'x20' in extent, with one brick chimney, to stand back 6' from the front line of the lot. Failure to comply with this requirement within the space of three years was to result in forfeiture of title to the lot. In at least one case, Waller enforced this requirement, reclaiming lots 21 and 22 5 from John Stretch when he failed to complete a dwelling on the land he had purchased.6 Robert Nicolson possibly succeeded in building a house on lot 26, for his title to the property was never challenged. This dwelling may have been nearing completion in June of 1752 when Nicolson purchased 18 prints at the Virginia Gazette office for the sum of £1.16.7 On the other hand, one wonders how Nicolson could have been in a position to build such a house so early in his life. Dendrochronology might well prove the house to be somewhat later.

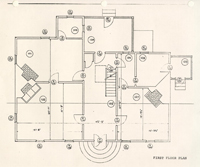

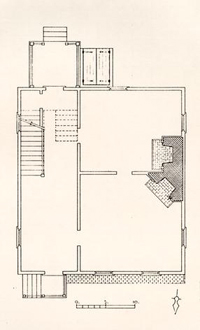

As originally completed, Nicolson's dwelling exceeded by a comfortable margin the minimum size requirements spelled out in his deed. Measuring 26' long by 26' deep, it was a 1½ story, gambrel-roof structure, laid out on a two-room-deep, side-passage plan. In its interior arrangement and outward form, this dwelling resembled the Orrell, Lightfoot and Tayloe houses here in Williamsburg. Significantly, the latter two structures were owned by important members of the gentry, though who actually occupied them during the period remains a matter of question.8

Generally, we fail to appreciate how elaborate such dwellings were when compared with the housing of most Virginians. 6 As late as 1784, one traveller observed that "only houses of the better sort" were provided with glass windows or interior plaster.9 In the context of contemporary housing, Nicolson's dwelling was a substantial accommodation, representing a fair degree of success and/or ambition. Along the same lines it is interesting to note that a comparable structure (the PowellHallam House) was erected on lot #30 by house carpenter, Benjamin Powell, who, like Nicolson, came to be regarded as a "highly respectable inhabitant of Williamsburg."10

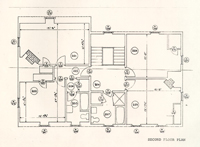

Sometime subsequent to completion of his house, Nicolson built an addition onto its western end. Consisting basically of two new rooms opening onto the existing stair passage, this addition nearly doubled the size of the house. Just when Nicolson erected this addition remains unclear. Circumstantial evidence points to the period around 1765-66.

Prior to that time Nicolson had been putting his financial house in order, bringing suit against at least nine different persons for unpaid bills.11 By 1765, he had apparently completed this litigation. As his circumstances improved, Nicolson gathered about himself a growing number possessions, many of them indicative of his increasing success. During the 7 two year period between 1764 and 1766, he built a small collection of books, purchasing a total of 19 volumes at the office of the Virginia Gazette—all of them works on history or divinity.12 Beyond their practical value, these books were important as emblems of their owner's social standing.

By 1766, Nicolson's family had grown to include five boys and an infant daughter, Rebecca.13 Assuming that the front, downstairs room served as the hall, a sort of multi-purpose living room, and the rear room as a lodging (see Chapter III), the family had perhaps only two chambers for its own use. As the size of Nicolson's household increased, these arrangements might have become inadequate, especially with the arrival of a daughter in 1766 who would eventually require a chamber separate from her brothers.14 Significantly, it was about this same time that Nicolson first advertised for "lodgers" in the Virginia Gazette,15 although he had rented a room to Cuthbert Ogle, as 8 early as 1755.16 In any event, the Gazette advertisement suggests that by 1766 he had completed the addition to his house and was in a position to take on lodgers. Documents indicate that by this time Nicolson had accumulated sufficient capital to buy additional land, to purchase slaves, to invest in merchandise for resale, and to hire journeymen for work in his tailoring business.17 Financially, he was in a position to build.

By the late 1760s, Nicolson was probably the leading tailor in Williamsburg. He appears to have been patronized extensively by Governor Botetourt, making numerous articles of clothing for Botetourt's slaves, livery for his house,servants and possibly clothing for his lordship as well. After Botetourt's death in 1770, Nicolson provided mourning attire for the Governor's household and numerous other articles at a cost of more than £135. In all, Lord Botetourt's account with his tailor amounted to nearly £217--a substantial sum.18

Nicolson continued to prosper. By 1773, he was employing at least one indentured servant, who had apparently "absconded". In August of that year, Nicolson advertised in the Virginia Gazette, offering a reward of ten pounds for the return 9 of one "John Bain, by trade a tailor".19 In 1774, Nicolson acquired property in the prime commercial area of Duke of Gloucester Street where he set up a mercantile business. In the deed of sale for this property, his name is followed by the designation, "Merchant" rather than "Tailor"--a significant change.20 It would appear that Nicolson had ascended to a new social plateau. With his new business established, the tailor-turned-merchant sailed for England, ostensibly on business, leaving his son William to "mind the store."21

With the approach of the Revolution, Nicolson began to perform public duties suggestive of his growing respectability. For a period of time, he appears to have been a public agent, procuring raw materials and finished components needed for the manufacture of arms by the colony. In January of 1776, Nicolson announced by way of the Virginia Gazette that he was authorized to purchase brass on behalf of the "Gun Manufactory" in Fredericksburg, and three months later, he was instructed by the Council of State to pay one Alexander Banks for "Gunn locks furnished the public."22

By the spring of 1777, Nicolson's circumstances were such that he "entirely discontinued taking in lodgers," 10 announcing his decision in the Virginia Gazette.23 Throughout the remainder of the century, he continued to operate as a merchant at his store on Duke of Gloucester Street, frequently soliciting the services of journeymen tailors and advertising various types of goods for sale.24 In 1797 Nicolson died at the age of 72, a prominent member of his community, whose passing merited the following notice in a Richmond newspaper:

DEATHS

On Friday last, in this city, Mr. Robert Nicolson, and [sic] old and highly respectable inhabitant of Williamsburg.25

The obscurity of Robert Nicolson's earliest years makes it difficult to determine just how far he moved up the social scale during the course of his lifetime. The 48 years we do know something about suggest that his progress was substantial. As he prospered, it is clear that Nicolson procured a continuing series of possessions which met his practical needs and, moreover, signified his new station in life. A horse, a servant, a lot, a house, books, slaves, a store: all point in succession to the increasing momentum of Nicolson's progress along the road to social and material success. In a larger context, these 11 possessions seem to exhibit the greater share of success enjoyed by merchants and tradesmen in general during this period and the changing role they played in society. The house that Robert Nicolson built is meaningful then in its expression of an individual tradesman's rise to respectability and its reflection of broader changes in the economic and social complexion of eighteenth-century Virginia.

II. PHYSICAL ANALYSIS

A. Exterior

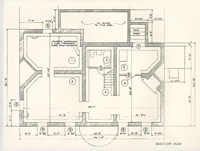

NOTE: All windows and doors are keyed to measured plans appended to the rear of this report.

SOUTH ELEVATION:

| Foundation: | Original. Cleaned and repaired in 1940. See Cogar diary, 11-18-40, 11-19-40. |

| Chimneys: | Original. Repointed in 1940. See Cogar diary, 10-7-40, 10-9-40. |

| Dormers: | All modern, replaced in 1940. See Cogar diary, 11-9-40, 11-14-40. |

| Window W/101: | Frame - Original. |

| Sash - Original. See Room #102 - south elevation. | |

| Stops - Original. | |

| Shutters - Installed 1940, replacing earlier louvered blinds. Present shutters based on early surviving shutter on north elevation. | |

| Window W/102: | Frame - Original. |

| Sash - Original. See Room #102 - south elevation. | |

| Stops - Original. | |

| Shutters - Modern. See Window W/101. | |

| Window W/103: | Frame - Original. |

| Sash - Original, repaired in 1940. See Room #105 - south elevation. | |

| Stops - Original. | |

| Shutters - Modern, see window W/101. | |

| Window W/104: | Frame - Original. |

| 13 | |

| Sash - Original. See Room #107 - south elevation. | |

| Stops - Original. | |

| Shutters - Modern, see window W/101. | |

| Windows | |

| W/201-5: | Completely replaced in 1940. |

| Window W/1: | Brickwork - Original. |

| Frame - Original. | |

| Sash - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Window W/2: | Brickwork - Original. |

| Frame - Original. | |

| Sash - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Window W/3: | Brickwork - Left jamb rebuilt. |

| Frame - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Sash - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Window W/4: | Brickwork - Left jamb rebuilt. |

| Frame - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Sash - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Door D/101: | Doors - Original. Louvered doors modern. |

| Transom - 19th century. See Room 104 - south elevation. | |

| Trim - Original except for sill and left jamb trim. Repair at bottom of right jamb. | |

| Steps - Date from construction of west addition. Relaid and underpinning rebuilt in 1940. See Cogar diary, 1023-40, 10-24-40. Relaid again in 1981. | |

| Trim: | Cornice at eave - Extensively repaired in 1940. See Cogar diary, 10-11-40, 10-30-40, 11-15-40, 11-16-40. Little if any of original appears to remain. |

| 14 | |

| Cornice at upper slope - replaced 1940. | |

| Corner Boards - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Siding: | Modern, installed 1940. |

| Roofing: | Cement-asbestos shingles installed in 1940. See Cogar diary, 10-29-40, 11-1-40, 11-4-40, 11-8-40. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Chimney: | See south elevation. |

| Attic Window: | Frame - Original. |

| Louver - Modern. | |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Windows W/211: | Frame - Original. |

| Sash - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. | |

| Stops - Old replacements [?]. | |

| Shutters - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Window W/212: | Frame - Original. Sill - Original [?]. |

| Sash - Modern. | |

| Stops - Original [?]. | |

| Shutters - Modern. | |

| Window W/110: | Frame - Original except for sill member. |

| Sash - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. See Room #101 west elevation. | |

| Stops - Original. | |

| Shutters - Modern. | |

| Window W/111: | Frame - Original. |

| Sash - Original. See Room #102 - west elevation | |

| 15 | |

| Stops - Old replacements [?]. | |

| Shutters - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Window W/6: | Brickwork - Original. |

| Frame - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Sash - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Trim: | Rake Boards - Modern, installed 1940. |

| End Boards - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Corner Boards - Modern, installed 1940. | |

| Siding: | Modern, installed 1940. |

| Foundation: | Original. See south elevation. |

NORTH ELEVATION

| Chimneys: | Original. See south elevation. |

| Roofing: | Cement-asbestos shingles installed in 1940. |

| Dormers: | Existing shed dormers altered to pedimented type in Cogar restoration of 1940 (see figs. 1 & 2). Window W/209 at stair landing was opened up at this time to provide additional light to the stairwell. There may originally have been a dormer in this location. All dormers are new, with possible exception of framing. All sash and trim is new. |

| Shed Extension: | Original dismantled in 1940 and extended to present size to allow for enlargement of porch area (see fig. 3). See Room #103. |

| Porch: | Built in 1930, following demolition of another brick porch area which was not original. |

| Bulkhead: | Framing - Rebuilt in 1940. See Cogar diary. |

| Doors - Installed in 1940. | |

| Foundation - Rebuilt in 1940. See Cogar diary. | |

| 16 | |

| Steps - Installed in 1940. See Room #5. | |

| Door D/109: | Door - Original. |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Window W/105: Frame - Original. | |

| Sash - Modern. | |

| Stops - Old replacements [?J. | |

| Shutters - Original. Ghost of original hardware visible. | |

| Window W/106: | Modern. See Room #106/8 - north elevation. |

| Window W/108: | Modern. See Room #103. |

| Window W/109: | Frame - Original except for sill. |

| Sash - Modern. See Room #101 - north elevation. | |

| Stops - Original [?]. | |

| Shutters - Original. Ghost of locking hardware visible. Lower portion of right shutter replaced. | |

| Window W/5: | Modern, installed 1940. See Room #1. |

| Door D/109: | Door - Original. |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Trim: | Cornice at eave. Extensively repaired or replaced 1940. See south elevation. |

| Cornice at upper slope. Replaced 1940. | |

| Cornice boards - All modern. | |

| Foundation: | At west end, original bulkhead access to addition was closed up during the 19th century. Cogar photo's show a large opening here in 1940 (see fig. 4). In 1940, a basement window was inserted here. |

EAST ELEVATION

17| Chimney: | See south elevation. |

| Attic Windows: | Frame - Modern (see figs. 5 & 6). See Cogar diary, 10-16-40. |

| Louvers - Modern. | |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Window W/206: | Frame - Modern. |

| Sash - Modern. | |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Shutters - Modern. | |

| Window W/207: | Frame - Modern. |

| Sash - Modern, probably installed in 1940. | |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Shutters - Modern. | |

| Door D/105: | Door - Modern. It is unclear whether this opening is original. See Room #106/8, east elevation, door 105. |

| Trim - Modern. | |

| Porch: | Added after 1940. See Cogar diary, 9-23-40, 10-14-40, 10-16-40, 12-14-40, 12-15-40, 12-17-40, 12-18-40 (see figs. 5 & 6). |

| Trim: | Rake boards - Modern. |

| End boards - Modern. | |

| Corner boards - Modern. | |

| Siding: | Modern, installed in 1940. |

B. Interior

ROOM #1 (Northwest Room - Cellar)

| Walls: | North - Original bulkhead opening closed up mid-19th century. Existing window frame installed 1940. |

| East - Junction of 18th century addition to original east portion of the house is clearly evident. No evidence of cellar window openings on west end of original portion of house. | |

| West - Substructure of hearth for Room #101 reinforced 1981. | |

| Framing: | Original. Short section of sill on east exterior wall of addition is lapped onto west sill of original house. Now hidden by lay-in acoustical ceiling, installed 1981. |

| Floor: | Lowered ± 18" in 1940. Concrete. See Cogar diary, 9-28-40, 10-2-40, 10-3-40, 10-4-40, 10-5-40, 10-7-40. |

| Window: | Frame - Installed 1940. See Cogar diary, 11-26-40. |

| Sash - Installed 1940. |

ROOM #2 (Southwest Room - Cellar)

| Walls: | North - Junction of this wall with original west foundation wall is visible. |

| East - Opening created through original west foundation wall to provide communication between east and west portions of the basement. This opening may date from the mid-19th century when the independent bulkhead access to the west addition was closed up. See Room #1 Walls: North. | |

| South - Junction of this wall with SW corner of original foundation is visible. | |

| Framing: | Original. Now hidden by lay-in acoustical ceiling installed in 1981. |

| 19 | |

| Floor: | Lowered ± 18" in 1940 - now concrete. |

| Window W/1: | Sash - Installed in 1940. |

| Frame - Original. | |

| Window W/2: | Sash - Installed in 1940. |

| Frame - Original. | |

ROOM #3 (Bathroom - Cellar)

| Walls: | East - Large openings made for ductwork, probably in 1940. Re-used in 1981 refitting. |

| South - Stud partition, erected 1981. | |

| Framing: | Original. Now hidden by lay-in acoustical ceiling installed 1981. |

| Floor: | Lowered ± 18" in 1940. Concrete. |

ROOM #4 (Passage - Cellar)

| Walls: | North - See Room #3 - Walls: South. |

| East - It is unclear whether the opening between Rooms #4 and #6 is original. | |

| West - There do not appear to have been any windows in this, the original west foundation wall of the original house. See Room #2, Walls: East for discussion of doorway. | |

| Framing: | Original. Now hidden by lay-in acoustical ceiling installed 1981. Sill at front door replaced 1940. See Cogar diary, 9-27-40. |

| Stair: | Installed 1940. See Cogar diary, 12-14-40. |

| Floor: | Lowered ± 18" in 1940. Concrete. |

ROOM #5 (Northeast Room - Cellar)

| Walls: | North - Original bulkhead opening (D/1). Cellar steps and cheek walls rebuilt 1940. See Cogar diary, 9-12-40, 10-12-40. |

| 20 | |

| East - Arch in fireplace foundation bricked up and provided with thimble for furnace flue, 1940. | |

| South - See Room #6 - Walls: North. | |

| West - See Room #3 - Walls: East. | |

| Framing: | Joists original. Sill at NE corner replaced 1940. Sill at bulkhead replaced 1981. See Cogar diary, 9-23-40, 9-26-40. Now hidden by lay-in acoustical ceiling installed 1981. |

| Floor: | Lowered ± 18" in 1940. Concrete. |

ROOM #6 (Southeast Room - Cellar)

| Walls: | North - Modern partition - installed 1981. |

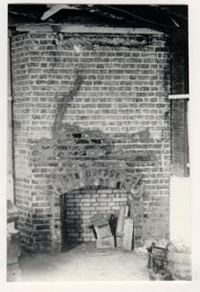

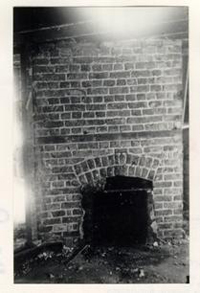

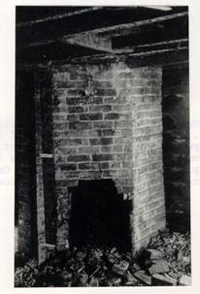

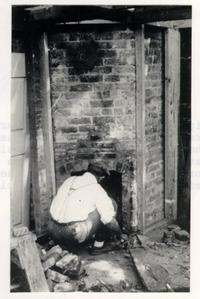

| East - Original fireplace remains essentially intact, including breast, arch, back and jambs. Original "semi-circular" hearth replaced in 1940. Substructure of 1st floor hearth above rebuilt in 1981. See Cogar diary, 10-25-40. | |

| South - Original brick wall. Openings rebuilt. See Exterior, South Elevation, Window #'s 3 & 4. | |

| West - See Room #4 - Walls: East. | |

| Framing: | Original, reinforced through the introduction of a built-up beam of six 2 x 10s running E-W which effectively reduces maximum joist span to about 91 611. Now hidden by lay-in acoustical ceiling installed in 1981. |

| Window W/8: | Sash - Installed 1940. |

| Frame - Installed 1940. | |

| Window W/4: | Sash - Installed 1940. |

| Frame - Installed 1940. | |

| Floor: | Lowered ± 18" in 1940. Concrete. |

ROOM #101 (Northwest Room - 1st Floor)

21NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Not shown in Cogar photos. |

| Window W/109: | Sash - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. Sash weights added in 1940. See Cogar diary, 11-3040. |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Paneling: | Two panels, bottom rail, and center stile under window have been replaced. Rail under window sill does not line up with peg holes in right hand stile. Entire area under window W/109 appears to have been reworked--possibly indicating that this opening was converted to a door and back to a window. |

| In section of paneling to the right of door D/112, both end stiles have strips added along their edges to make them a full 4" in width. The reason for this is unclear unless door D/112 was cut down at some point, and the resulting gap taken up at both ends of the paneling. | |

| Door D/112: | Door - Original. Some patching of holes left by earlier lock is visible. |

| Hinges - H-L surface mounted on door side with modern screws. | |

| Lock - Not original. Small iron rimlock. | |

| Trim - Original at head and left jamb. Trim at right jamb and entire backband replaced in 1981 due to insect damage. | |

| Trim: | Cornice - Installed 1940. Cogar photo shows room before installation (see fig. 7). |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original [?]. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/111: | Door - Original. Some patching of holes left by earlier lock is visible. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted with screws on door side, mounted behind trim on jamb side with barrels let into bead of architrave. Barrels are welded to hinge straps, indicating that they have been removed at some point, though no indication of earlier hinges is visible. | |

| Lock - Brass rimlock not original. See Cogar diary, entries for 9-14-40, 11-30-40, 12-3-40, and 12-9-40. | |

| Trim - Original, except for patch on right jamb to receive keeper. | |

| Paneling: | Original. Bottom rail filled with putty in 1981 where insect damage had occurred. See Nicolson House photo album, #81-DS-20855. |

| Trim: | Cornice - See North Elevation. |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original [?]. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | See Room #102 - North Elevation. |

| Door D/113: | Door - Original. Some patching of holes left by earlier lock is visible on stile and lock rail. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted with screws on door-side mounted behind trim on jambside, with barrels let into bead of architrave. No evidence of earlier hinges is visible. | |

| 23 | |

| Lock - Brass rimlock is not original. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Paneling: | Original. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Installed 1940. |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - May be modern. Joint occurs about midway between D/113 and the east wall of Room #101. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Fireplace: | Firebox - Rebuilt in 1940. |

| Surround - Rebuilt in 1940. | |

| Hearth - Original [?]. | |

| Mantel: | Dates from the 1940 "restoration, design by Washington Reid and S.P. Moorehead of Colonial Williamsburg. See Cogar diary, 10-25-40, 11-19-40. |

| Window: | Sash - Both date from 1940 restoration. |

| Stops - Original. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Paneling: | All paneling appears to be early, though an odd junction of two sections occurs below left jamb of window W/110. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Installed 1940. |

| Chair rail - Original excepting one modern section on left side of fireplace. | |

| Base - Modern on left side of fireplace. On right side of fireplace, base joint lines up with joint in paneling above. | |

| 24 | |

| It is not clear whether this portion of the base is original | |

| Plaster: | All plaster dates from the 1940 "restoration". |

ROOM #102 (Southwest Room - 1st Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Note visible, though appears to be original in Cogar photos (see figs. 8 & 9). One of these photos shows a brace, running up from the sill of the partition to a major post in the wall of the stair passage |

| Door D/113: | Door - See Room #101 - South Elevation |

| Hinges - See Room #101 - South Elevation | |

| Lock - See Room #101 - South Elevation. | |

| Trim - Original | |

| Fireplace: | Firebox and brest - Rebuilt in 1940. |

| Surround - Probably dates from 1940. | |

| Hearth - Original [?]. | |

| Mantel: | Original. |

| Paneling: | Original. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Installed in 1940. See Cogar diary entries for 11-8-40, 11-9-40, 11-11-40, 11-12-40 (see figs. 9, 12 & 13). |

| 25 | |

| Picture Molding - Appears to be old. A "Picture Slip" is mentioned in the 1798 specification for painting the interior of the St. George Tucker House. molding was already in place at the time of the restoration (see figs. 8, 9, 11 & 12). | |

| Chair rail - original. | |

| Base - original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | See Room #105 - West Elevation. |

| Door D/114: | Door - Original. Some patching of holes left by earlier lock is visible. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted on door-side with screws, mounted behind trim on jamb-side with barrels let into beat of architrave. | |

| Lock - Brass rimlock not original. | |

| Trim - Original, excepting a patch on right jamb to receive existing keeper. | |

| Paneling: | Original. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Installed in 1940. See North Elevation. |

| Picture molding - Possibly original. See North Elevation. | |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates to the Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Partially shown in Cogar photos. Exterior view shows adjoining corner posts of original and later portions of the house. SW corner post is rectilinear in plan rather than L-shaped, suggesting that construction occurred before the last quarter of the eighteenth century (see figs. 7, 10, & 11). |

| Window W/101: | Sash - Both original. Sash weights added 1940. |

| Stops - Original. | |

| 27 | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Window W/102: | Sash - Both original. Sash weights added 1940. |

| Stops - Original. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Paneling: | Original. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Installed in 1940. |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Cogar photos indicate replacement of stud immediately adjacent to chimney (see figs. 14 & 15). |

| Window W/111: | Sash - Both original. Sash weights added in 1940. See Room #101 - North Elevation. |

| Stops - Original at head and sill. Side stops are modern. | |

| Paneling: | Original. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Installed in 1940. See North Elevation. |

| Picture Molding - Possibly original. See North Elevation. | |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | ± 95% Original. |

| Paint: | Color found by Cogar was "green." See diary, 9-6-40. Present color applied in 1901. |

ROOM #103 (Shed Room - 1st Floor)

GENERAL NOTES

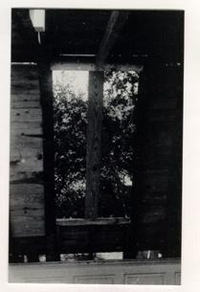

This room is entirely modern, being somewhat larger in extent than the original shed room which was razed in 1940 (see figs. 16 & 3). Mortises are visible on some of the later Cogar photos where the sills and joists of this room framed into the rear sill of the west addition. also visible in these photos are indications of shelving on the south wall of the original room. No original fabric seems to remain except the framing of the south wall.

ROOM #105 (Passage - 1st Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Closet: | Upper door - Original. Stile patched. |

| Lower door - Dates from 1940, replaced a 19th or 20th century door. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Hinges - H-type, let in flush with surface of stile, mounted with screws. | |

| Pulls - Installed 1940. | |

| Interior - Original, consisting of pine sheathing secured with wrought finishing brads. Floor is original also. | |

| Paneled side - Original. | |

| Door D/109: | Door - Original, except for patching of right hand stile and lock rail to close holes left by earlier hardware. Right stile also patched at middle right panel. Paint lines indicate former location of larger rimlock. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted on door-side with modern screws; mounted behind trim on jamb-side with barrels let into architrave. Paint lines on door indicate that hinges have been remounted. | |

| 30 | |

| Lock - Carpenter-type not original. Brass escutcheon obliterated by black paint applied in 1981. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Door bar and brackets - Installed 1940. See Cogar diary, 12-7-40. | |

| Window W/209: | All modern, installed in 1940 (see figs. 1, 2, & 17). |

| Paneling: | Paneling at stair landing is original. |

| Trim: | Chair rail - Original at stair landing. |

| Base - Original at stair landing, modern at rear door. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Stair - Original. |

| East Wall - Not visible. | |

| Stair: | Railing - Original. |

| Newel - Replaced in 1940. See Cogar diary, 9-26-40. | |

| Balusters - All appear to be original. | |

| Treads - Old, possibly original. | |

| Risers - Old, possibly original. | |

| Door D/107: | Door - See Room #106/8 - West Elevation. |

| Hinges - See Room #106/8 - West Elevation. | |

| Lock - See Room #106/8 - West Elevation. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Door D/102: | Door - See Room #107 - West Elevation. |

| Hinges - See Room #107 - West Elevation. | |

| 31 | |

| Lock - See Room #107 - West Elevation. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Door D/108: | Door - Original. Does not show on measured elevations. Some patching of holes left by earlier lock is visible on stile and lock rail. |

| Hinges - H-L surface mounted on door-side with modern screws, mounted behind trim on jamb side. Original [?]. | |

| Lock - Brass rimlock not original. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Paneling: | Spandrel - Original [?]. |

| East Wall - Original. | |

| Soffit - Not visible on measured elevation. Original. | |

| Trim: | Cornice - Installed in 1940. See Cogar diary, entry for 10-23-40. |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original. Patched at left of Door D/102. | |

| Plaster: | All dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Sill is modern, an installation dating from the Cogar restoration of 1940 (see fig. 12). Other framing not visible. |

| Door D/101: | Doors - Original. Patching of holes left by knocker visible on inner stile of right-hand door. Both doors shimmed at top. Ovolo on top of right lock rail is a patch. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted with screws on door-side, mounted behind trim on jamb-side with barrels let into bead of architrave. Paint lines on both doors indicate that hinges have been remounted. | |

| 32 | |

| Lock - Large iron rimlock not original. | |

| Bolts - Both appear to be antiques, mounted with modern screws. | |

| Transom - Narrow muntins. Appears to date from the early 19th century. | |

| Stops - Top and side stops have been replaced, probably when 19th century transom was installed. | |

| Trim - Original. Patch on left jamb trim of floor. | |

| Door bar and brackets - Installed in 1940. See Cogar diary, 12-7-40. | |

| Paneling: | Original. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Added during Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Peg Strip - Added during Cogar restoration of 1940. See Cogar diary, 11-18-40. | |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Shows on Cogar photos, however (see figs. 8 & 9). It is unclear whether this wall, the west exterior wall of the original house, had windows. A brace runs downward from the major post situated in the middle portion of the wall, tying into the sill below. |

| Doors: | D/114 - Original. See Room #102 - East Elevation. |

| Hinges - See Room #102 - East Elevation. | |

| Lock - See Room #102 - East Elevation. | |

| 33 | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| D/111 - Original, except for stops which are nailed in. | |

| Hinges - See Room #101 - East Elevation. | |

| Lock - See Room #101 - East Elevation. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Paneling: | Original. Paneling to the left of D/113 sits further off the wall than elsewhere. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Added during Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | ± 80% original. |

| Paint: | Original color found by Cogar was "yellow." See diary, 9-6-40. Present color applied 1981. |

| Plan: | West elevation may originally have had window openings prior to construction of west addition. |

ROOM #107 (Southeast Room - 1st Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Cogar diary and photos indicate that this partition was altered in 1940 (see discussion of Door D/103 below). |

| Door: | Door - Moved to present location in 1940 from its original position just left of the fireplace (compare figs. 18 & 19). This alteration may explain the reference in Cogar diary to "patching and moving the 34 dining room - kitchen partition" (see entry for 9-17-40). In moving this door, it was necessary to cut the brace which formerly ran from the plate of the partition down to a major post in the wall of the stair passage. In fig. 20, the jamb posts of the original opening appear to have remained in place. There are no lath marks on these posts since they were covered with trim. Note lath marks on stud next to present opening. This may be the door frame referred to in Cogar diary, 11-19-40. |

| Hinges - See Room #106/8 - South Elevation. | |

| Lock - See Room #106/8 - South Elevation. | |

| Paneling: | Moved intact in 1940 to accommodate relocation of Door D/103 (figs. 18 & 20). |

| Trim: | Cornice - Original. |

| Chair rail - Moved intact with paneling. | |

| Base - Moved intact with paneling. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Cogar photos reveal that a window opening on this wall, dating perhaps from the 18th or early 19th century was closed up in 1940 (see figs. 5, 6, 21 & 22). |

| Fireplace: | Firebox - Rebuilt, probably in 1940. See Cogar diary, 10-4-40. |

| Hearth - Relaid in 1940. See Cogar diary, 10-25-40. Rebuilt in 1981. Prior to that time, the existing substructure of the hearth appeared to be an old repair. At the point where it bore against a diagonal header, the brick half-arch was laid to a shim, fashioned from an old weatherboard. Existing brick was reused when hearth was relaid in 1981. | |

| 35 | |

| Surround - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. See Cogar diary, 12-7-40. | |

| Mantel - Shelf, bed molding and frieze are original. Plaster surround and backband probably date from Cogar restoration of 1940. | |

| Paneling: | Plain panels to either side of mantel are original. Cap molding also appears to be original. Small panel section forming transition from chimney to north wall is modern. Raised paneling on right side of fireplace is original excepting a patch in the top rail, installed when the window was removed. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Original. |

| Chair rail - Sections applied to plain paneling are modern. Sections applied to raised paneling are original except patched area where window was removed. See Cogar diary, 9-13-40. | |

| Base - All original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Window W/104: | Sash - Original. |

| Stops - All modern except head stop. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Window W/103: | Sash - Original. Two horizontal muntin sections replaced at lower left and center of bottom sash. See Cogar diary, 11-19-40. |

| Stops - Original. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| 36 | |

| Paneling: | Original. Panel sections join with half-stiles under right jamb of Window W/104. Extreme right end of paneling terminates in a stile 10 1/4" wide. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Original. |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/102: | Door - Original. Patching is visible on right stile at upper hinge, and on left stile and lock rail where earlier hardware left holes. |

| Hinges - Modern butt type, screwed into jamb lining with barrels let into architrave. Outlines of earlier H-L hinges are visible on left-hand side of door. | |

| Lock - Brass rimlock not original. | |

| Trim - Original, patched at keeper. | |

| Paneling: | Original. |

| Trim: | Cornice - Original. |

| Chair rail - Original. | |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | ± 80% original. |

| Paint: | Original color found by Cogar was "blue." See diary, 9-6-40. Present color applied 1981. |

ROOM #106/108 (Northeast Room - 1st Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

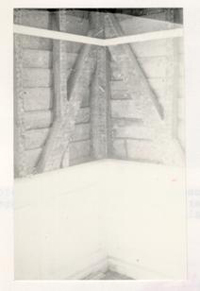

| Framing: | All framing in this wall was exposed during 1981 restoration. Extensive alteration was evident, much of it in the form of new studs "scabbed" onto original members. Corner braces at both ends have been cut, that on the left to 38 accommodate a new window opening, that on the right to allow replacement of the sill and installation of additional studs. Lower edge of right brace retained wain edge. Suitable for dendrochronology. |

| Window W/105: | Sash - Modern. |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Trim - Modern. Notches for head member to lap into jamb posts suggests that the existing opening is slightly larger than the original. | |

| Window W/106: | Entire window is modern, dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Fireplace: | Bricked up and plastered, probably in 1940. |

| Door D/105: | Door - Modern. It remains unclear whether this opening is original, since the framing could not be examined. The Frenchman's Map shows an outbuilding situated east of the house, suggesting perhaps that a door did exist here in the 18th century. An opening appears in this location prior to the restoration. |

| Hinges - Modern. | |

| Trim - Modern. | |

| Trim: | Chair rail - Original, reused [?]. |

| Base - Original, reused [?]. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | See Room #107 - North Elevation. |

| Door D/103: | As noted in discussion of Room #107, D/103 was moved to present location in 1940. |

| Door - Original. Some patching of holes left by earlier hardware is visible. | |

| Hinges - Modern butt type screwed into jamb lining with barrels let into architrave. Indications of earlier H-L hinges visible on door. | |

| Lock - Carpenter type, not original. Marked: "No. 60/IMPROVED LOCK." | |

| Trim - Original. Right backband a replacement. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/107: | Door - Removed. |

| Hinges - H-L, only jamb side remains. Mounted behind trim on jamb-side with barrels let into bead of architrave. | |

| Trim - Original, excepting right backband. | |

| Trim: | Chair rail - Original, reapplied with wire nails [?]. |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | Original floor has been removed and replaced with lumber subflooring, covered with linoleum. |

| 40 | |

| Paint: | Cogar diary fails to mention scrapings in this room. Present color applied 1981. |

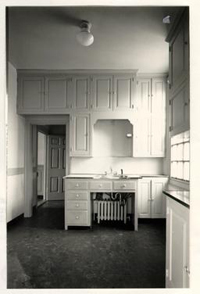

| Plan: | In 1940, what is now Room #106/8 was divided to create a kitchen and pantry. This arrangement remained until 1981, when the dividing partition was removed, returning the room to its original size (figs. 23 & 24). |

ROOM #201 (Northwest Room - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Window W/210: | Modern. Probably dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Trim: | Corner boards - Modern. Probably date from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Trim: | Base - Original, reapplied with cut nails |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Cogar photos show original stud at chimney, later removed (see figs. 25 & 26). |

| Door D/202: | Door - Original. Some patching of holes left by earlier hardware is visible on stile and lock rail. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted with screws. | |

| 41 | |

| Lock - Not original. 19th century square plate latch mounted with modern screws. Cast relay bar and night latch. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Trim: | Base - Modern [?]. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Fireplace: | Breast and firebox - Firebox rebuilt in 1940. See Cogar diary, 9-29-40, 9-30-40, 10-1-40. Breast original. |

| Surround - Modern, probably dating from 1940. | |

| Hearth - Rebuilt 1940 [?]. | |

| Mantle: | Original except for backband and shelf. |

| Shelving: | Appears to be old, possibly original. These shelves show up on the Cogar photo (see fig. 25). |

| Window W/211: | Sash - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Trim- Jamb pieces appear to be original. Head and sill trim are modern. | |

| Trim: | Modern [?]. Appears worn, though applied with cut nails. No indication of earlier holes for wrought brads. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | ± 60% original. Flooring at north wall is old, reused from another source. |

| 42 | |

| Paint: | Present finishes applied 1981. |

ROOM #202 (Southwest Room - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Closet framing. All modern, dating from Cogar restoration of 1940 (see figs. 27 & 28). Framing at door into passage may be original. |

| Door D/205: | All modern. |

| Door D/204: | Door - Original. It is unclear whether this opening is in its original position. Some patching of holes left by earlier hardware is visible on stile and lock rail. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted with screws. | |

| Lock - Not original. 19th century square plate latch mounted upside down with modern screws. Cast relay bar and night latch. | |

| Trim - Original. Patched at keeper. | |

| Trim: | Base - Original piece 18" long remains in place at extreme left, where it attaches to the masonry of the chimney. Remainder may be old reused in new location. Base inside closet is modern. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Appears original in Cogar photos (see figs. 29 & 30). |

| Trim: | Base - Possibly original. Applied with cut nails with filled holes for T-head brads. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Cogar photos show some reinforcing of original framing in 1940 (see figs. 29 & 30). Framing of addition differs from original portion in detailing of the plates carrying the upper slopes, and in the use of bracing on the lower slopes. |

| Window W/201: | Sash - Modern. |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Trim - Modern. | |

| Trim: | Corner boards - Date from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Base - Original. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Window W/212: | Sash - Modern. Probably dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Trim: | Base - Original. |

ROOM #203 (West Bath - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940 (see fig. 31) . |

| Door D/208: | Modern, dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Original studs. Joist into which they are jointed is either reinforced or replaced (see fig. 30). |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Appears original in Cogar photos (see figs. 29, 30 & 32). |

| Window W/202: | Sash - Modern. |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Trim - Modern. | |

| Trim: | Corner boards - Modern. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | See Room #202, East Elevation. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | Linoleum over subfloor over original floor. |

| Plan: | This room was created in 1940 by subdivision of a larger space which included what are now Rooms #203 and #204. |

ROOM #204 (Bath Vestibule - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/206: | Door - Removed. |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Trim: | Modern. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Closet Wall - Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940 (see fig. 31). See diary, 9-25-40, 10-22-40. |

| East Wall - Not visible. | |

| Door D/207: | Modern, probably dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Trim: | Base - Modern, probably dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Modern. See Room #203 - North Elevation, General Notes. |

| Door D/208: | Modern. See Room #203 - North Elevation. |

| Trim: | Base - Modern. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | See Room #202 - East Elevation. |

| Trim: | Base - Modern. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | Original. |

| Paint: | Present finishes applied in 1981. |

| Plan: | This room may have had a window opening on the west wall prior to construction of the addition. |

ROOM #205 (West Passage - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/202: | Door - Original. See Room #101 - South Elevation. |

| Hinges - See Room #101 - South Elevation. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Trim: | Base - Modern. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/201: | Door - Modern. Probably dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Trim - Modern. | |

| 47 | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/204: | Door - Original. See Room #202 - North Elevation. |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Door D/206: | Door - Removed. See Room #204 - North Elevation. |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Trim: | Base - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Trim: | Peg Strip - Appears to be old - original location? |

| Base - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | Original. |

| Paint: | Present finish applied 1981. |

ROOM #206 (Passage - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Roof framing appears original in Cogar photo (see fig. 17). |

| Window W/209: | Modern. See Room #105 - North Elevation. |

| Stair: | Railing - Original. |

| Banisters - Original. | |

| Curb - Original. | |

| Steps - Original [ ? ]. 30% of floor at landing is original. | |

| Risers - Original [?]. | |

| Paneling: | Original. See Room #105 - North Elevation. |

| Trim: | Base (at landing) See Room #105 - North Elevation. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/211: | Door - Original. See Room #209 - West elevation. |

| Hinges - See Room #209 - West Elevation. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Door D/213: | Door - Original. Patches on stile and lock rail. See Room #208 - West Elevation. |

| Hinges - See Room #208 - West Elevation. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Trim: | Base - Modern [?]. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Appears partially modern in Cogar photos. Possible original framing reinforced in 1940. |

| Door D/209: | Original. Patches on stile and lock rail. See Room #207 - North Elevation. |

| Hinges - See Room #207 - North Elevation. | |

| Trim - Original. | |

| Trim: | Base - Modern. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/206: | Door - Modern. See Room #205 - East Elevation. |

| Hinges - See Room #205 - East Elevation. | |

| Trim - Modern. | |

| Trim: | Modern [?]. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | ± 600 original. |

| Paint: | Present finish applied 1981. |

ROOM #207 (East Bath - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | See Room #206 - South Elevation. |

| Door D/209: | Door - Original. Patching of holes left by earlier hardware is visible in stile and lock rail. |

| 50 | |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted with screws. | |

| Lock - Not original. 19th century square plate latch with cast relay bar and night latch. | |

| Trim - Original [?]. No bead. | |

| Closet | |

| Partition: | Modern. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Original. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. Appears original in Cogar photos (see figs. 29, 30 & 33). |

| Window W/203: | All modern. Installed in 1940 (see fig. 33). |

| Trim: | Corner boards - Modern. Probably installed 1940. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Closet partition - Modern. |

| West Wall - Not visible. Appears original in Cogar photos (see figs. 30, 31). | |

| Door D/210: | Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | Linoleum on subflooring on original floor [?]. |

| Paint: | Present finishes applied 1981. |

| Plan: | Altered in 1940 by insertion of closet and plumbing fixtures. |

ROOM #208 (Northeast Room - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Closet partition - Modern, probably installed in 1940. |

| North Wall - Not visible. | |

| Door D/214: | Modern. |

| Window W/208: | Sash - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Trim - Modern. | |

| Corner boards - Modern, probably dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. | |

| Base - Original, except on closet partition. Re-applied with cut nails. Filled holes for wrought brads. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Closet partition - Modern, probably installed in 1940. |

| East wall - Not visible. | |

| Furred out area in chimney - Modern. | |

| Window W/207: | Modern, probably installed in 1940. |

| Trim: | Closet corner boards - Modern. |

| 52 | |

| Base - Original, reused in present location [?]. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

SOUTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Furred out area - Modern, covers fireplace and chimney breast. This dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| South Wall - Not visible. | |

| Trim: | Corner boards - Modern, probably dating from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Base - Original, except furred out area. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/213: | Door - Original. Some patching of holes left by earlier hardware is visible in stile and lock rail. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted with screws. No evidence of earlier hinges. | |

| Trim - Original. No bead. | |

| Trim: | Base - Original, re-applied with cut nails. Filled holes for wrought brads. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | ± 66% Original. Most replaced boards near north wall. |

| 53 | |

| Paint: | Present finishes applied 1981. |

| Plan: | In 1940, this room was altered by insertion of a closet, and closing off of the fireplace and chimney. |

ROOM #209 (Southeast Room - 2nd Floor)

NORTH ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Trim: | Base - Original. |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

EAST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Closet partition - Modern, installed in 1940. |

| East Wall - Not visible. | |

| Fireplace: | Breast and firebox - Rebuilt in 1940 (see figs. 34 & 35). |

| Surround - Rebuilt in 1940. | |

| Hearth - Rebuilt in 1940. | |

| Mantel: | Original except for shelf and backband. |

| Window Seat: | Modern. |

| Shelving: | Modern. |

| Door D/212: | Modern. |

| Window W/206: | Sash - Modern, probably installed in 1940. |

| Stops - Modern. | |

| Trim - Modern. | |

| Trim: | Base - Modern. |

| Cornerboards - Modern. | |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

WEST ELEVATION

| Framing: | Not visible. |

| Door D/211: | Door - original. Some patching of holes left by earlier hardware is visible on stile and lock rail. |

| Hinges - H-L, surface mounted with modern screws. No indications of earlier hinges. | |

| Lock - Iron rimlock not original. | |

| Trim - Original. No bead. | |

| Trim: | Base - Original, re-applied with cut nails |

| Plaster: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

GENERAL NOTES

| Ceiling: | Dates from Cogar restoration of 1940. |

| Floor: | ± 33% original, most near north wall. |

| Paint: | Present finishes applied 1981. |

| Plan: | Closet added 1940. |

C. SUMMARY CHRONOLOGY

| 1751 | Robert Nicolson purchased lot 26 from James Spiers. |

| c. 1751-2 [?] | Original, side-passage house completed. |

| c. 1766 [?] | Additions and Alterations

|

| 1788 | Humphrey Harwood worked at house.

|

| c. 1840 | West bulkhead closed up.

|

| 19th & 20th c. | Various modifications--Numerous owners.

|

| 1940 | House purchased by James Cogar and restored.

|

| 1966 | Acquired by Colonial Williamsburg. |

| 58 | |

| 1981 | Renovated by Colonial Williamsburg.

|

III. INTERPRETIVE ISSUES

A. The Side-Passage Plan

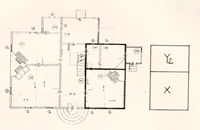

We have seen that the side-passage layout of Robert Nicolson's original house resembled similar arrangements at the Lightfoot, Tayloe, Orrell and Palmer houses here in Williamsburg (Fig. 36). Marcus Whiffen has suggested that this plan was characteristically urban, drawing comparisons between it and the interior arrangement of terrace houses in London.26 If surviving examples are a reliable indication, the side-passage house did remain primarily an urban phenomenon in Virginia until the end of the eighteenth century.27

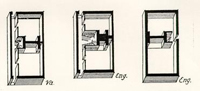

In order to understand the urban association of the side passage in Virginia, it is necessary to consider the social performance of the house type, setting aside Henry Glassie's morphological notion of a "2/3's Georgian plan."28 As Edward A. Chappell points out, the side-passage house was less a reduction of some other plan form than one of several alternative packages 54 for the familiar hall/parlor house.29 Architectural historian Dell Upton has suggested that this hall/parlor core was occasionally re-oriented in urban contexts so as to create a building one room wide and two rooms deep. According to Upton, the individual units of structure 17 at Jamestown (the so-called "First Statehouse") represent a transposition of the lobby entrance vernacular house plan, popular in Southeast England during the seventeenth century (Fig. 37).30 Like its rural English counterpart, each Jamestown unit consisted of a front and back room, both served by a centrally located chimney against which a flight of stairs ascended to the upper floor.

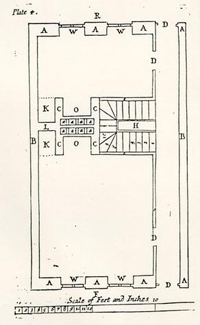

Many seventeenth-century terrace houses in London exhibited the same general layout, with the additional provision of an entry or a narrow passage which afforded independent access to the front and rear rooms. Such an arrangement greatly increased the privacy of first floor rooms and provided an intermediate space between the dwelling's threshold and its interior spaces--a refinement which may be seen in a plan from Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises, published about 1703. (Fig. 38).

The relevance of this plan to Robert Nicolson's house is clear when we consider that his dwelling initially exhibited 55 the same basic hall/parlor/passage formula. The original front and rear rooms (corresponding to those in Moxon's plan) conform closely to Henry Glassie's "Y2X" formula for hall/parlor dwellings in Middle Virginia (Fig. 39).31 Both of these rooms, as well as the upper floor, were independently served by a side passage running the entire depth of the house. Like Moxon's terrace house then, the original Nicolson plan is best understood as a re-oriented hall/parlor unit with a passage added along its side.

In densely developed areas of London where street frontage was a premium commodity, this two-room-deep plan made complete sense. The reasons for its use in Williamsburg are less clear. The half-acre lots provided for in the 1699 act "Directing the Building of the ... City of Williamsburg" resulted in lot fronts that were approximately 80 feet wide. Significantly, each of the surviving side-passage houses in Williamsburg seems to have been built on one of these undivided, half-acre parcels. The popularity of this plan could hardly have resulted from any restriction on lot widths. On the contrary, remarks of contemporary observers make it clear that the lots in Williamsburg were thought to be rather generously proportioned. Commenting in 1724 on the layout of Williamsburg, Hugh Jones observed:

The town is laid out regularly in lots or square 56 portions, sufficient each for a house and garden; so that they don't build contiguously, whereby may be prevented the spreading danger of fire; and thus also affords a free passage for the air, which is very grateful in violent hot weather.32

Here Jones identifies the open space between buildings as a positive and distinguishing feature of Williamsburg. Baron de Graffenried appears to have had similar considerations in mind when he laid out the town of New Bern, North Carolina, in 1710:

Since in America they do not like to live crowded, in order to enjoy a purer air, I accordingly ordered the streets to be very broad and the houses well separated one from the other .... 33

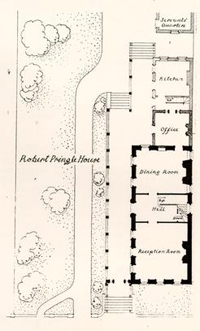

In Williamsburg, open space created what Peter Martin has called a "garden town"34--a village-like setting where, according to Jones, inhabitants might dwell "comfortably, genteelly, pleasantly and plentifully ... in [a] delightful, healthful and ... thriving city."35 It may be then, that the popularity of the side-passage house in Williamsburg resulted 57 partly from a desire to minimize the density of street front development, whereby hygienic open spaces and gardens could become an important part of the town's aspect. Such appears to have been the case in Charleston where large numbers of dwellings (called "single houses") are oriented with their long axes perpendicular to the street, creating large open spaces between adjacent buildings. (Fig. 40). Significantly, numerous residents chose to face their piazzas towards the gardens in these spaces.36

According to Martin, the eighteenth-century Virginian came to see his garden as a "palpable sign of civilization and urbanity."37 A perceived association of the side-passage house with gardens and open, healthful urban space might have invested this plan-type with an aura of gentility, especially suitable for appropriation by aspiring tradesmen like Robert Nicolson and Benjamin Powell. For wealthier citizens, the contrasting scale of townhouse and country seat provided a satisfying parallel to the modes of accommodation enjoyed by the gentry in England as they moved to and fro between London and their estates in the country. Through the town/country nature of gentry life it expressed and the "genteel" quality of urban space it helped to create, the side-passage house admirably embodied the gentlemanly self-concept of those affluent Virginians who periodically 58 converged on Williamsburg, and served as well the ambitions of those who aspired to join their ranks. In spite of apparent similarities, the side-passage plans of London and Williamsburg seem to have resulted from intentions that were really quite different.

The same may be said of the passage spaces themselves. Central passages (as opposed to porch entries) began to appear in Virginia probate inventories around 1720.38 Historians who have traced social changes occurring in the colony at that time attribute the appearance of these spaces to a growing desire for privacy and social segregation as society became increasingly stratified.39 At this point the passages of London and Virginia were not fundamentally different. Both functioned as circulation areas, providing a measure of privacy for the lower rooms. What ultimately distinguished the Virginia passage, however, was its performance as a primary living space.

Between the first and last quarters of the eighteenth century, diaries, travel journals, and probate inventories illuminate a gradual transformation of the passage from "Entry" 59 to "Summer Hall" to "Saloon."40 Furnished with several tables and as many as a dozen chairs, this space ultimately became a focal point of domestic activity in affluent households. Here, one might receive guests, read, play, nap, dance, engage in conversation, or simply pass the time on a hot day with as little discomfort as possible. The growing use of this room was, perhaps, the most important factor of all in the development of the side-passage plan. For any given hall/parlor unit, this arrangement nearly doubled the size of the passage, increasing its potential as a living space, and adding considerably to its effect as an impressive, ceremonial entry. From a practical point of view, the exterior exposure of this enlarged passage offered a full measure of light and ventilation, commensurate with the increasingly important role the space was assuming in the daily routine of wealthy Virginians. A further benefit of this new plan was the removal of the chamber from the street, with its noises, odors and curious bystanders.

The path leading backward from Robert Nicolson's sidepassage house to the townhouses of London is an uncertain one at best. If the appearance of this plan-type here in Williamsburg is to be adequately accounted for, it must be examined as a solution to local needs and problems--As the passage became an increasingly important living space, Virginians sought to 60 repackage the old hall/parlor house in a way that allowed for such change. This re-formulation was encouraged by the prominence of gardens and open areas in prevailing concepts of urban space. The resulting plan form created large spaces and garden areas between adjacent buildings, achieving an open, genteel kind of urban environment. At the same time it allowed for removal of a private space, the chamber, to the rear. It is not in London, then, but here in Virginia, that we find the origins of Robert Nicolson's side-passage house.

B. The Extension

Little more than a decade seems to have passed before Nicolson undertook to enlarge his side-passage house. We have already considered some of the practical considerations which might have prompted him to do so. However, it is in a broader, social context that this extension is best understood. Nicolson's addition nearly doubled the size of his house, providing what appear to have been three additional bedchambers and a large, public room. What was this new public space and why was it added? There are at least three possible answers to this question:

1) Perhaps Nicolson's old front room had remained a relatively accessible public space, resembling earlier halls in the diversity of persons and activities it accommodated, while elsewhere in Virginia, the hall had become a formal space for entertaining--a place where those possessions expressive of one's place in society were assembled and placed on display.41 In this controlled setting, formalized exchanges with peers and inferiors proclaimed the owner's position in the scheme of things. As Nicolson moved ahead financially and socially, he might have seen the need for a newer, more formal hall--aloof from the mainstream of daily routine and indicative of his growing respectability.

This explanation is not particularly convincing since the original house incorporated a sizeable passage, indicating 62 that access to the hall had been subject to some degree of control from the very beginning. Chances are, this hall had always been a fairly formal and controlled setting.

2) One might suggest on the other hand, that Nicolson's addition represented a partitioning of the newly enlarged house between himself and his prospective lodgers. In such a case, the newer, west rooms might have encompassed a hall and chamber for the owner, with the older rooms across the passage given over to the use of lodgers. The old hall would then have performed like Joseph Kidd's "very elegant parlour ...appropriated to the use of lodgers" at the old Custis house.42 A similar division of the Prentis house appears in the York County records in 1776, wherein Elizabeth Prentis was given the use of the dwelling's western rooms along with the stair passage.43 In recent years, Sabine Hall was divided in this same manner among members of the Wellford family.

The trouble with this theory is that the architectural finishes of the first floor, mostly dating from the enlargement of the house, make little sense when viewed as two separate domains. They suggest instead, an integrated domestic environment--similar perhaps, to one of Dell Upton's three room plans with its "perplexing" fourth room accorded only minimal 63 architectural embellishment.44

3) In this context, a third possibility seems more likely: that Nicolson's new public room represents a large dining space of the type seen at the residence of Peyton Randolph, where the dining room (added about 1755) is the largest and most elaborately appointed space in the house.45 Large dining rooms of this sort began to appear in Virginia during the third quarter of the eighteenth century, usually in association with larger gentry houses. In such cases the old hall or parlor was sometimes retained as a secondary public room.46

Evidence for this sort of arrangement appears in the 1774 inventory of George William Fairfax of Belvoir, in Fairfax County. From this inventory it is clear that Fairfax's dining room was the largest space on the ground floor, having three window curtains versus two in the parlor. The best furnishings, moreover, were brought together in this dining room, where the chairs, looking glass, hangings and fireplace equipment were all appraised at a higher value than those in the parlor.

But the superior status of Nicolson's new dining space, relative to the old hall or parlor, finds no clear expression in 64 architectural terms. On the one hand, it was the largest room, adorned with a picture rail and the best chimney piece in the house. However, it originally had no cornice like that which embellishes the old hall--superior attributes are shared between two spaces.47

A similar pair of rooms is to be seen at the house of silversmith James Geddy. The back room, largest of all, is believed to have been the dining room. A doweled and blindnailed floor together with an elaborate buffet for the display of plate, ceramics and glass are indicative of the room's social importance. Otherwise the room is exceedingly plain. In contrast, the smaller southwest room, probably the hall or parlor, is embellished with wainscotting and a cornice. But here the flooring is faced-nailed--a technique often reserved for lesser rooms. As at the Nicolson house, we find certain "best room" traits shared between two spaces.

The uncertain relationship of these two rooms calls to mind a similar pair of spaces at Wetherburn's Tavern--the "Bullhead Room" and the "Great Room". The latter was a large, rather plain space. Architecturally speaking, only the massive chimney piece and the size of the room itself would lead one to conclude that it was the best room. In the Bullhead Room, a 65 smaller, parlor-like space, the panelled chimney breast might lead one to conclude that it was the primary space. In Wetherburn's case, the superior status of the Great Room was clarified by the high quality of its furnishings.48 This was probably true of Nicolson's new dining room, as well. At the Nicolson house and elsewhere, the ambiguous architectural relationship of the dining room and parlor reflected a prevailing uncertainty regarding the status of these two rooms as their social function and position in the dwelling's spatial hierarchy began to change.49

This change, and the large dining spaces resulting from it, were restricted primarily to the more opulent houses in Virginia. The association of these grand dining rooms with the highest echelon of society might explain Nicolson's wish to incorporate such a space into his dwelling. Like the books he owned or the prints he purchased, this room was an urbane statement of his social and material attainment. The house of Benjamin Powell offers still another example of a large dining space in the house of an upwardly mobile tradesman, this one resulting from Powell's renovation of the structure during the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Viewed against the domestic environments created by these tradesmen, the extension of Robert Nicolson's house makes complete sense, offering 66 unexpectedly rich insights into the processes of architectural change in early Virginia.

C. Front vs. Rear

As noted earlier, Robert Nicolson's dwelling reached its present extent when he built an addition onto its western end, possibly about 1766. In the construction of this west addition, great care was taken to unite the new and existing portions of the house behind a unified, symmetrical facade. No such efforts are apparent in the rear however, where the addition is fully articulated (Fig. 41). It was only important that the house appear symmetrical and integrated from the street, regardless of its actual disposition. Edward Chappell has previously noted a similar phenomenon at the Peyton Randolph House. Much as this lack of correspondence between the real and apparent nature of an object would trouble today's architectural thinkers, it presented no difficulty to the eighteenth-century mind. Indeed, the acceptance of this dichotomy seems to have been a fundamental characteristic of the eighteenth century's aesthetic orientation. An extraordinary example of this acceptance is to be seen at Independence Hall in Philadelphia, where failure to relate window arrangement to the structure's interior layout resulted in two first floor windows being bisected by interior walls (Fig. 42). Clearly, formulation of the building's external appearance proceeded quite apart from any consideration of its interior arrangement. The formal programme of the building exterior was the preeminent concern, and the resulting elevation was imposed without regard to the spaces 68 which lay behind it.

Here in Virginia, the mansion house at Shirley plantation exhibits a similar lack of integrity between interior and exterior where, in the entry, one of the windows is completely obstructed by the great stair. This window exists for the sole purpose of maintaining an orderly composition of the mansions' east exterior elevation. The stair itself, having "no apparent means of support" is actually carried on two wrought iron bars concealed behind its scrolled soffit.

These examples reveal a decided emphasis on superficial effects as opposed to integral qualities. Many other buildings of the period exhibit evidence of this tendency. In London, speculative housing was occasionally built of timber, but cased with a thin veneer of brick, mimicking the appearance of a solid brick wall. Even the method of pointing these veneer walls, with white putty let into tinted mortar joints, was a visual ploy, intended to simulate the appearance of finer brickwork.50