William Finnie House Architectural Report, Block 2 Building 7 Originally entitled: "Architectural Report: Semple House (Draft)"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1016

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

ARCHITECTURAL REPORT

SEMPLE HOUSE

BLOCK 2 BUILDING 7

Colonial Lots 257 & 258

DRAFT

INTRODUCTION

American architecture, from the establishment of the first colony until well into the nineteenth century, seems to have been almost totally eclectic. In the past one hundred years or so, however, architects in the country have made architectural statements which have had no small influence on world architecture, particularly in the twentieth century.

Most of the Colonial period buildings of any architectural ambition can be traced directly to European or especially English prototypes. This in no way means that American colonial buildings had no character of their own, for while being based on the architecture of the mother country, they developed a character of their own influenced by a new environment -- buildings which were very much American.

During the period of the American Revolution, when great segment of the American populace had become decidedly disenchanted with things English, they began to fall more than ever under the influence of Europe, especially the French whose aid in the war could not easily be forgotten. The new nation set itself up as a republic, based on democratic principles of ancient Greece and Rome, so there is little wonder that the classical revival which was so modish in Europe would have found immediate acceptance among Americans. The champion of this new influence was Thomas Jefferson, who introduced into America the ultimate classical expression in architecture -- the temple-form building (Virginia State Capitol). It is the temple-form building, or more specifically, the tripartite pedimented house which is the subject of this paper. Loosely defined, the tripartite pedimented house is a three-part composition: a center pedimented pavilion, two stories in height, flanked by matching one-story wings, the whole very much in the Anglo-Palladian style. Although readily catagorized within the Palladian sphere, it seems to have been eighteenth century English pattern-book authors who actually were responsible for developing the prototype on which the American tripartite pedimented houses were based (if indeed they were based on pattern-book designs).

From all indications, the tripartite pedimented house enjoyed a certain degree of popularity continuously during the Federal and Greek Revival periods in America, however this paper is concerned primarily with those buildings dating from the time of the Revolution through the first quarter of the nineteenth century, which were built for the most part in Virginia and North Carolina. Chapter Four is a listing of the major houses under consideration which are mentioned in the preceding chapters. (The reader should refer to this section when necessary.)

With any discussion of the Classical Revival in America, the name of Thomas Jefferson is forever found; and with the tripartite pedimented house in particular, Jefferson connections are inescapable. Chapter Two is a record of primarily architectural and genealogical ties between Jefferson and tripartite pedimented houses of Virginia and North Carolina, with special emphasis on the Semple House, the "harbinger of the Federal style".*

It was the original intent of this paper to study the Semple House and various buildings of similar form in Tidewater Virginia. As this project progressed, more and more Semple-type houses came to light in North Carolina, especially in the Halifax area.** Because of the abundance of these houses in so close a proximity, an investigation was made to find any possible connections between Halifax and Virginia (especially Williamsburg), this being the subject of Chapter Three.

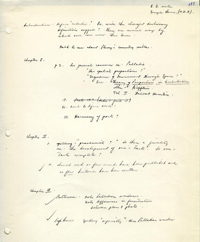

Chapter I

The American tripartite pedimented house, which reached its peak of popularity during the first years of the 19th century, can trace its lineage to Vicenza's most famous and prolific architect, Andrea Palladio (1518-1580). Palladio became an indefatigable scholar of the Roman buildings of antiquity, having begun studying and measuring them in his youth. His knowledge and reliance on classical architecture, combined with his very personal sense of design, scale, and proportion, resulted in a whole genre of buildings which are somewhat divorced from the mainstream of late Italian Renaissance architecture, and is generally designated as simply Palladian.

Much of Palladio's finest and most personal work was residential. Having become an architect of prominence and influence, he was given numerous commissions by the wealthy and aristocratic families of Venice and Vicenza for their city dwellings or pallazzos, as well as their country retreats on the nearby Brenta River.

It was with the country house, due to its rural nature, that Palladio used his greatest imagination and inventiveness to create houses of outstanding monumentality and sophistication while employing such mean materials as brick and stucco. He depended to a great extent on proportion and scale to achieve grandeur, rather than rich materials and lavish detail which characterized his urban buildings. Very often the country house interiors were completely devoid of architectural ornamentation (which, in Italy, was vastly expensive even then), but by painting the architecture on the walls a la trompe l'oeil the interior was given great style and a rich effect, all at a fraction of the cost.

2.The planning scheme which Palladio favored incorporated a central, imposing dwelling for the master of the house and his family, with symmetrically placed dependencies flanking it on one or both man axes. The formally planned central dwelling house nearly always had its main floor, or piano nobile, raised a full story above the ground surface. The piano nobile was the entertainment or formal living level, usually having as its most imposing room a centrally placed entrance salon or great hall (preferably two stories in height), off which the important receptions rooms were situated. Interior stairways, too, related to the great hall, but were de-emphasized in architectural importance. Beneath the piano nobile was the service floor which related directly to the dependencies; and above was a private floor reserved for the family. (See followi[ng] illustratio[ns)]

The exterior of Palladio's villas was characterized by the extensive use of great classically-inspired porticos used to accent the massive stuccoed surfaces of the walls and the low roof. Additional low arcades and colonnades acted as connecting links between the central dwelling and the formally placed dependencies flanking it, thus increasing the apparent size and importance (and convenience) of the country estate. This very grand and pretentious scheme, which satisfied all the requirements of the fashion-conscious north Italian gentry, was to become the paragon for the English country gentlemen as well during the next century.

The Palladian style came into full bloom in England by 1725 and lasted until about 1745, due in part to the rise of the Whigs in 1714. Whiggism represented the views of the majority of wealthy and educated who fostered a high level of moral and aesthetic values. The Grand Tour of Europe became an even more important part of the young gentleman's education, at which time he familiarized himself with the visual background of classical civilization. Also, landed property

The Four Books of Architecture, Andrea Palladio, plate XXXI.

The Four Books of Architecture, Andrea Palladio, plate XXXI.

The Four Books of Architecture, Andrea Palladio, plate XLV.

5

continued to afford the key to political and social influence. The effect on the idealistic concept on the tastes of Whig England can be summarized by saying that it gave sanction to classical correctness and to conformity with the discipline of ideal, classical forms in architecture. Hence, it is no wonder that the work of Palladio as seen in his Quattro Libri del Architecture (1570) caught the fancy of the status-seeking Englishman. Here was found the qualities of design, based on classical forms, which approximated English requirements.

The Four Books of Architecture, Andrea Palladio, plate XLV.

5

continued to afford the key to political and social influence. The effect on the idealistic concept on the tastes of Whig England can be summarized by saying that it gave sanction to classical correctness and to conformity with the discipline of ideal, classical forms in architecture. Hence, it is no wonder that the work of Palladio as seen in his Quattro Libri del Architecture (1570) caught the fancy of the status-seeking Englishman. Here was found the qualities of design, based on classical forms, which approximated English requirements.

In 1715 two books were published which actually launched the new architectural style: Colin Campbell's Vitruvius Britannicus and the first English edition of Paladio's Quattro Libri, translated by Nicholas Dubois with plates by Giacomo Leoni. Campbell claimed Palladio to be "the ne plus ultra of his art",* and Leoni the font of "the true rules, unknown even to Michel Angelo and Brunelleschi."* The Palladian villa, originally combining farm buildings with a compact residence, offered various patterns capable of adaptation and enlargement into palatial mansions. In short, Palladian discipline ensured a stately level of performance. By the middle of the 18th century the Whig Party, Idealism, and the Palladian Revival had lost its full impetus in England and it was about the same time that we find the first Palladian buildings of any academic significance in the mid-Atlantic colonies of America. This lag in transmitting the new fashion from England was due in part to the scarcity of up-to-date pattern books in this country and to the fact that the Palladian movement was a monumental style, utilizing classic trim and highly articulated planning. Both of these were beyond the means of the Colonists, whose fortunes were modest 6 compared to the fabulous wealth of the English landed gentry. Even in the great building years from 1750 to the Revolution, American essays in Palladian architecture were unassuming when compared to English examples. It is true that in the years prior to this, certain Paladian design influences were seen among the typical Georgian houses of the day, but not until Mount Airy (Richmond County, Virginia, 1758) was a truly academic Palladian building constructed.

7The intent of this report is, of course, to trace only one aspect of the broad-based Palladian movement -- the tripartite pedimented house; or, what might be loosely called, the "Palladian farm house." The parti of this type building is quite simple, having a two-story pedimented temple-form central bay flanked on each side by single-story pedimented wings. The plan generally consisted of a typically Palladian great hall, occupying the central pavilion, with a room (or rooms) flanking it on each side. Ideally the great hall would envelop the whole center pavilion, thus eliminating a second story, however this extravagance was most often usurped in favor of bed chambers above. The exterior generally is characterized by its small size, arrangement of parts and great monumentality.

The tripartite pedimented house, though very definitely a part of the Palladian movement, interestingly enough has not been traced directly to the designs of Andrea Palladio himself. It seems that it was the English architects who actually developed this particular form which was to become so popular in America. As a part of his architectural vocabulary, Paladio continually employed the central pedimented pavilion, one-story wings, porticos, tripartite schemes; but apparently never in a configuration exactly equivalent to that of the "Palladian farm house." The only possible exception might be the "Temple that is below Trevi" which is illustrated in Palladio's Quattro Libri, Book 4, plate 71 and 72. (See illustrations.) This building has little significant relationship, other than the mere form of the building above the podium. As far as scale, proportion, and combination of elements is concerned, not much valid evidence of its influence is discernible.

By contrast, in the English handbooks, tripartite pedimented buildings were illustrated from around the middle of the 18th century through the first years of the 19th century. For the most part, these

The Four Books of Architecture, Andrea Palladio, plate LXXI. Temple that is below T[revi.]

The Four Books of Architecture, Andrea Palladio, plate LXXI. Temple that is below T[revi.]

The Four Books of Architecture, Andrea Palladio, plate LXXII. Temple that is below T[revi.]

10

were conceived as small, romantic, decorative architectural accents for the embellishment of a garden or an ambitious country seat. Most often they were intended to be shooting lodges, retreats, cottages, bridges, farm houses and the like, rather than a manor house itself. The very fact of the small size of these pattern book design prototypes would in some way account for the popularity they enjoyed in this country.*

The Four Books of Architecture, Andrea Palladio, plate LXXII. Temple that is below T[revi.]

10

were conceived as small, romantic, decorative architectural accents for the embellishment of a garden or an ambitious country seat. Most often they were intended to be shooting lodges, retreats, cottages, bridges, farm houses and the like, rather than a manor house itself. The very fact of the small size of these pattern book design prototypes would in some way account for the popularity they enjoyed in this country.*

For years, architectural historians have almost unanimously given credit to Robert Morris' Select Architecture (1757) for being one of the most influential source books of the Palladian style in this country; and there can be little doubt that Morris' book did have tremendous influence on the design of houses like Brandon, Battersea, Belle Isle, and Monticello. For the tripartite pedimented house, too, architectural historians have traditionally designated Morris' Select Architecture, Plate XXXVII, as being its prototype, which is not, it seems, too unreasonable an assumption. (See following illustration.) But in various other lesser-known English pattern books, far more closely derivative prototypes can be found, especially among the work of William Halfpenny, the creator of some of the most personal and unacademic architectural pattern book designs of the 18th century. Unlike Gibbs, Paine, Burlington and the other prominent architects whose books were patronized by the noble and wealthy, much of William Halfpenny's work appealed to the middle or upper-middle class man who aspired for the fashionable but on a scale which he would find more comfortable and with which he could cope financially.

Plan and Elevation Shown in Plate 37, in Robert Morris' Select Architecture

Plan and Elevation Shown in Plate 37, in Robert Morris' Select Architecture

In 1742, William Halfpenny in collaboration with "...John Halfpenny, architects, and carpenters, Robert Morris, surveyor, and T. Lightoler, Carver" published The Modern Builder's Assistant. This is one of the earliest known pattern book sources for the "tripartite pedimented house", plates 25, 39 and 59 being of special interest primarily for their room arrangement. (See following illustrations.) Each plan I basically three rooms in size, formally arranged, with a large center hall flanked by a pair of lesser rooms. This is in essence the planning scheme favored in American "Palladian farm houses" during the late 18th century, and will hereafter be referred to in this paper as Type I. In general this type plan tends to date from an earlier period than the bulk of houses of its type in this country and numbers in the minority. (They include: Tazewell Hall, White Hall, Semple House, Fortsville, The Grove and The Hermitage. Of special note are the similarities in concept between Plate 39 and White Hall; and between the plan of Plate 59 and Tazewell Hall.)

Plate 26 in The Modern Builder's Assistant is an early illustration of a tripartite house (with side appendages) comprising a two-story center section with flanking one-story wings. The plan, an admittedly awkward and inarticulate arrangement, is basically not unlike the other plans previously discussed (except in size). Here we find a large central room with lesser rooms flanking it, but with the notable addition of a narrow entrance stair hall. Houses which incorporate such a stair hall in their plan will hereafter be designated as having Type II plans. Following the publication of this book in 1742, other English architectural pattern book authors, including Halfpenny himself, further developed this planning scheme and its corresponding elevation into designs which are recognizable today as built in North Carolina and Virginia during the early 19th century.

[Box Structures: Type 1 and Type 2]

[Box Structures: Type 1 and Type 2]

The Modern Builder's Assistant, William and John Halfpenny, Robert Morris and T. Lightoler, 1742, plate 25.

The Modern Builder's Assistant, William and John Halfpenny, Robert Morris and T. Lightoler, 1742, plate 25.

The Modern Builder's Assistant, William and John Halfpenny, Robert Morris and T. Lightoler, 1742, plate 26.

The Modern Builder's Assistant, William and John Halfpenny, Robert Morris and T. Lightoler, 1742, plate 26.

The Modern Builder's Assistant, William and John Halfpenny, Robert Morris and T. Lightoler, 1742, plate 39.

The Modern Builder's Assistant, William and John Halfpenny, Robert Morris and T. Lightoler, 1742, plate 39.

The Modern Builder's Assistant, William and John Halfpenny, Robert Morris and T. Lightoler, 1742, plate 59.

The Modern Builder's Assistant, William and John Halfpenny, Robert Morris and T. Lightoler, 1742, plate 59.

Following the publication of The Modern Builders Assistant, its authors, William Halfpenny, Robert Morris, and T. Lightoler, went on to publish their own pattern books, each of which is vastly important in the development of the Palladian farm house. In 1752, William Halfpenny's small pattern book, Useful Architecture, was published which was primarily a collection of small farm building designs. By this time, it seems that Halfpenny had become quite interested in the possibilities of a tripartite parti, for there are several interesting variations on that theme in this book: plates 3, 6, 13,14, and 17. (See following illustrations). Of these, plate 17, number 1, is of special interest, as it is, in essence, the prototype of American Palladian farm houses. The elevation as well as the plan is quite close to that of Type II when analyzed. In order to see this relationship more closely, first disregard the rear shed additions to the flanking wings and remove the front hall partition (see illustration) and at once the plan of the Wimberly House and the Harris Place is recognizable. Next, widen the entrance hall remove one leg of the stair in order to gain an entrance to the wing rooms, and you have the plan of Mt. Grove, Rhodes House, Sallie Billie, Pugh House, and the others of that group. Another pattern book by William Halfpenny, Design for Farm Houses, published in 1759, has similar tripartite farm houses, but none so obviously the prototype of American work as those of his Useful Architecture.

In 1762, a small pattern book by T. Lightoler, The Gentleman and Farmer's Architect, was published in London. This book includes designs for a number of small farm houses with walled-in yards and appropriate outbuildings, many of which are indebted to Halfpenny's Useful Architecture and Morris' Select Architecture for their design. Plate 10, a "Farm House", is typical of Halfpenny's designs which appeared earlier in Useful Architecture;

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 3.

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 3.

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 6.

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 6.

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 13.

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 13.

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 14.

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 14.

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 17. [and two smaller drawings]

Useful Architecture, William Halfpenny, 1752, plate 17. [and two smaller drawings]

The Gentleman and Farmer's Architect, T. Lightoler, 1762, plate 10.

20

and, like Halfpenny, Lightoler adds a bit of variety (and humor) to the standard tripartite pedimented parti as seen in plate 17, "... a Lodge House or Farm in the Chinese Taste." Plate 18, "Out Office"*, is identical to the aforementioned plate 59 in The Modern Builders Assistant (which Lightoler had obviously created for that book as indicated by his signature on the plate).

The Gentleman and Farmer's Architect, T. Lightoler, 1762, plate 10.

20

and, like Halfpenny, Lightoler adds a bit of variety (and humor) to the standard tripartite pedimented parti as seen in plate 17, "... a Lodge House or Farm in the Chinese Taste." Plate 18, "Out Office"*, is identical to the aforementioned plate 59 in The Modern Builders Assistant (which Lightoler had obviously created for that book as indicated by his signature on the plate).

In 1768 Thomas Rawlins, Architect, published this pattern book, Familiar Architecture, which was followed by later editions in 1789 and 1795. This book dealt primarily with gentlemen's and tradesmen's houses in the English Palladian style, some of which were three part pedimented schemes. (Plates III and XXII.) (See following illustrations) The elevations of these, and not their plans, can be included among the English pattern book designs which might have influenced American architect/builders.

These mid-eighteenth century pattern books, especially Rural Architecture, naturally had an influence on later architects. Plate V in John Plaw's Rural Architecture, published in 1785, illustrates a "Cottage or Shooting Lodge" which is quite close to Halfpenny's work thirty years earlier. (See following illustration) The façade of this building is merely a polished-up version of Plate XVII of Halfpenny's Rural Architecture; unlike the plan (Plate IV) which is a far more sophisticated conception much influenced by the Adam style. It is not only possible, but probable, that there were other 18th century pattern books which illustrated tripartite pedimented houses in the Palladian style, but at present they are unknown to the author.

The Gentleman and Farmer's Architect, T. Lightoler, 1762, plate 17.

The Gentleman and Farmer's Architect, T. Lightoler, 1762, plate 17.

The Gentleman and Farmer's Architect, T. Lightoler, 1762, plate 18.

The Gentleman and Farmer's Architect, T. Lightoler, 1762, plate 18.

Familiar Architecture, Thomas Rawlins, 1768, plate II.

Familiar Architecture, Thomas Rawlins, 1768, plate II.

Familiar Architecture, Thomas Rawlins, 1768, plate III.

Familiar Architecture, Thomas Rawlins, 1768, plate III.

Familiar Architecture, Thomas Rawlins, 1768, plate XXII.

Familiar Architecture, Thomas Rawlins, 1768, plate XXII.

Rural Architecture, John Plaw, 1785, plate IV and plate V.

Rural Architecture, John Plaw, 1785, plate IV and plate V.

From the preceding discussion of English pattern books of the 18th century, it is known that there was a considerable degree of English precedent for the tripartite pedimented houses in America. What is not known however, is how this style of architecture was introduced into this country, whether by a pattern book itself, an English trained craftsman/builder, or developed by an enlightened native American architect.

As discussed earlier in this chapter, Palladian farm houses can be divided into two distinct groups with respect to plan -- Type I and Type II -- although there is negligible difference in exterior form from one to the other. Why were there two different plans? Was one a development of the other? Do Type II plan houses out-number those of Type I because there is more pattern book precedent to be found for Type II? Why was the tripartite pedimented parti not generally employed on other than houses of modest size?

From the information available, it would seem that plan Type I and II were independent of each other from their inception in America; that is to say, that one did not develop from the other. It is true that Type I plan hoses tend to predate those with Type II plans, which would suggest that Type II would have been an outgrowth of Type I, but this does not seem to be a valid theory. It must be remembered that during the 1760's, when Whitewall and Tazewell Hall were built, Brandon and Battersea (both Type II plans) are thought to have been under construction also. Thus, both plan types were introduced at approximately the same time, each type apparently having its own prototype. Following these initial efforts, houses of both plan Types were built simultaneously in Virginia and North Carolina for a period of about fifty years with little or no noticeable change within each type itself.

30Of the Palladian farm house style in the mid-Atlantic states of America, Type I plan houses seem to number decidedly in the minority. (There are only seven examples known to the author.) Though a more academically Palladian approach, Type I plans had their inherent drawbacks: the main floor is limited to only three rooms (one of which is a circulation element) and a proper location for the stairway presents grave practical and aesthetic limitations.

The problem of the stairway was not encountered by the designers of the first Palladian farm houses -- Tazewell Hall and Whitehall -- because the entrance salon o each was allowed to rise the full two-story heights of the central pedimented pavilion, thus eliminating a second floor and the stair completely. This, of course, was the Palladian ideal in planning, but unhappily is not to be found in the houses which followed. During the next decade, between 1772 and 1776, William Pasteur of Williamsburg built his Palladian tripartite pedimented house (Semple House) on Francis Street which, interestingly enough, bears more relationship with Whitehall than its neighbor, Tazewell Hall. Unlike its American predecessors, however, the entrance salon of the Semple House does not rise the full height of the central pavilion but is sacrificed to accommodate bedrooms on a second floor, thus introducing a stairway into the plan. In order not to destroy symmetry and proper character of the central entrance salon (where vertical circulation would quite naturally be located), the Semple House stair is tucked away inconspicuously in a wing, winding precariously to the second floor. This is a highly successful solution aesthetically, but leaves much to be desired from a practical point of view. If, as it is supposed, the Semple House was a prototype of later Palladian farm houses, it seems only natural that a more practical stairway should have been sought. Unfortunately, practicality over-ruled aesthetic consideration in later houses, causing a 31 partial breakdown of Palladian ideals. The stairway was then brought out of its insignificant position in the wing and into the entrance salon -- a quite natural development indeed. But, no matter how the stairway was positioned in the salon, it assumed an awkward and unnatural appearance. (This is quite forcibly pointed out at The Hermitage.) The lack of adequate space on the main floor of these houses was easily augmented with the addition of rooms to the rear of the entrance salon which, at the same time, solved the problem of circulation by allowing the entrance salon to become solely a circulation element. (Such an addition was made to nearly every Type I plan house under consideration.) Considering the drawbacks of the Type I plan, there is little wonder that the Type II plan had a far greater appeal, for it, with a fraction of additional space, solved most to the problems inherent in Type I.

One of the most interesting aspects of American architecture, during the Colonial and Federal periods, is that the embellishment of a house did not necessarily increase or decrease in direct proportion with its size. In few countries of the world other than American can there be found a great deal of houses of small dimension and scale which were self-consciously designed and richly detailed. This phenomenon of American architecture is not easily explained, but is nevertheless quite interesting, and seems to be especially applicable to "Palladian farm houses." A prim example is Sallie Billie (Scotland Neck, N. C.), a hose of diminutive size which is a carefully thought out, well proportioned building with unusually elaborate details.

As with all buildings of architectural pretension at any time in history, a harmony of two basic elements are imperative for good design: scale and proportion. As the same time, it seems that size imposes little or no limitations upon the sensitive designer. However, 32 in the case of the tripartite pedimented house, sheer size is a key element in achieving good proportion and scale. If the basic parti becomes expanded in size beyond its intrinsic limitations, the whole design suffers aesthetically. This is readily apparent when analyzing the main façade of Mosby Hall, Kelvin Grove, and even Woodbourne. Here we find that the once pleasing balance of elements is completely lost due to the two story double-pile-width of the imposing central pavilion with its very massive pedimented end, all of which greatly overpowers the flanking one story wings. Thus, the charm, sophistication, and subtle monumentality which is so much a part of the "Palladian farm house" is transformed into a very heavy-handed and awkward pile.

This limiting factor of size, which is very arbitrarily imposed on the design of these buildings, might well account for the fact that so few dwelling houses with a tripartite pedimented parti were published in 18th century English pattern books whose clientele was generally limited to the landed gentry. It seems certain that other English architects of the Palladian school (beside Halfpenny and Lightoler) and indeed Palladio himself must have studied the possibilities of a tripartite pedimented scheme, but soon realized the inherent aesthetic pitfalls of such a parti where adapted to buildings of more than the most modest size.

From all indications, it seems that the tripartite pedimented house enjoyed its greatest popularity not in Europe or England, but in Virginia and North Carolina, at a time when all enlightened Americans were becoming disenchanted with English Georgian architecture, and began riding the tide of classicism as introduced by Thomas Jefferson just before the Revolution. The tripartite pedimented house sanctioned a complete break with colonial design, then quite a daring change, but nevertheless 33 fashionable. And best of all, one was able to create a house with considerable architectural pretensions without appearing pretentious, to create an aura of monumentality, but yet not of monumental size.

Chapter 2

Some Jefferson Corrections

For years it has been thought by architectural historians that several of the Virginia "tripartite pedimented houses" were designed by Thomas Jefferson, although there has yet to be uncovered any indisputable proof of this supposition. Before launching into so involved a discussion, it is well to set down a few facts about Jefferson's early life and education.

Jefferson's first known interest in architecture was while he was a student at the College of William and Mary (1760-1767), at which time it is known that he purchased an architectural book from an old cabinet-maker at the college gate.* Before coming to Williamsburg, Jefferson had spent several years of his childhood at Tuckahoe on the James River, and at Shadwell, the Jefferson's simple house in rural Piedmont Albermarle County. Thus, coming to Williamsburg in 1760 was probably young Jefferson's first introduction to town planning and architecture of any academic quality. Undoubtedly, the fine houses, gardens, and public buildings of Williamsburg impressed him very much, even though, unknown to him, these buildings were provincial renderings of a style already much out of date in England. Later in his life, though, after Jefferson had developed his architectural taste and knowledge, he was very critical of Virginia's architecture (Williamsburg's in particular), thinking it quite unrefined and old fashioned.**

2At William and Mary, Jefferson came under the influence of William Small who introduced him to George Wythe, the great jurist and first professor of law in America, and under whom Jefferson read law. Considering Jefferson's intimate relationship with Wythe and his apparent interest in architecture, it seem probable that he would have cultivated the friendship of Wythe's father-in-law, Richard Taliaferro, one of Williamsburg's most distinguished architect/builders of the day. It is suggested by Thomas T. Waterman that Taliaferro could, in fact, have been Jefferson's architectural mentor, introducing him to his architectural library and, in particular, the works of the sixteenth century architect, Andrea Palladio, under whose influence Jefferson was to become drawn.*

Unfortunately, most of Jefferson's early correspondence, account books, and architectural drawings were destroyed by the fire at Shadwell on February 1, 1770, but it is known that as early as 1767 Jefferson had begun studies for Monticello, and until 1770 he was busy perfecting his schemes with the profound influence of three books: James Gibbs' Rules for drawing the Several Parts of Architecture and Book of Architecture, Robert Morris' Select Architecture, and Paladio's Four books of Architecture** (and possibly the books of Halfpenny and Lightoler***). His early architectural drawings for Monticello, dated by authorities as before 1770, are carefully drawn and do not suggest the work of a novice, 3 thus it seems probable that he had already become proficient through instruction and practice, which could have covered the whole period of his life in Williamsburg after 1760.*

Three pre-Revolutionary houses - Brandon, Battersea, and the Semple House - have much in common; so much, in fact, that it seems doubtful that they could be the work of more than one designer. Jefferson also has been given credit as their architect, due not only to their definite architectural kinship, but to Jefferson's friendship with the builders of each of these houses. Jefferson was a groomsman at Nathaniel Harrison's wedding in 1765, who later built Brandon. The builder of Battersea, John Banister, was a close friend of Jefferson and with his wife, Martha Bland, there was a blood relationship through the Blands and Randolphs. To assign any building to Jefferson before the building of Monticello is to rely on circumstantial evidence alone, but the available evidence seems strong enough to do so. The houses built between 1765 and 1770, (i.e., Brandon and Battersea) are derived for the most part from Robert Morris' plates, renderings of some of which occur in Jefferson's manuscript drawings with modifications that occur in the buildings themselves.** The two early studies for Monticello are obviously based on Plate XXXVII of Morris' Select Architecture, the first having a great deal in common with the Semple House plan, "to such a degree that there can be no doubt that they are by the same author".***

The Semple House (1772-1777) was built by Dr. William Pasteur of Williamsburg and the extraordinary relations (architectural, family, and otherwise between Jefferson and the Pasteurs give more and more credence to the commonly held belief that Jefferson did in fact design 4 the famed Semple House. One of the closest ties between one man and another is that of blood, and for that reason it would be well to begin by establishing the Jefferson-Pasteur-Stith kinship.

The closest kinship with Jefferson was through William Pastuer's wife, Elizabeth Stith, daughter of the Reverend William Stith (1707-1755), President of William and Mary College, and Judith Randolph Stith, his wife. Judith Randolph Stith (born c. 1724) was the daughter of Thomas Randolph of Tuckahoe (and Judith Fleming, his wife), who was the son of William Randolph I of Turkey Island (and his wife, Mary Isham). Thomas Jefferson's mother Jane Randolph, was the daughter of Isham Randolph of Dungeness and the granddaughter of William Randolph I of Turkey Island. Therefore, Elizabeth Stith Pasteur and Thomas Jefferson were second cousins through the Randolphs.

Reverend William Stith was also a grandchild of William Randolph I of Turkey Island through his mother, Mary Randolph, who was a daughter of William Randolph I, thus making Jefferson a double second cousin of Elizabeth Stith Pasteur. Since it is known that Jefferson spent much of his childhood at Tuckahoe, he would have undoubtedly met and known his cousin of about the same age, Elizabeth Stith, who, with her mother (who was born at Tuckahoe), would undoubtedly have visited there.

Establishing a blood tie between William Pasteur's family and Thomas Jefferson is not quite so simple. William was the son of Jean (John) Pasteur (died 1741), who married second Mary Harris (died 1746) some time before 1729. Jean Pasteur, a Frenchman, had immigrated to this country in 1700 aboard the "Nassau", the list of passengers including:

"Jean Pasteur* 5 Martha Harris (Pasteur) was descended from Thomas Harris (died 1730) and Mary, his wife, of Henrico County.

Charles Pasteur and sa femme

Jean Pasteur"

Dr. William Pasteur's sister, Ann Pasteur, married (before 1759) Thomas Craig, the son of Alexander Craig (1717-1776) and Maria Maupin, a granddaughter of Gabriel Maupin (who, incidentally, immigrated to this country on the "Nassau" in 1700 with William Pasteur's grandfather, Jean Pasteur.) It was Ann Pasteur Craig who, in a letter dated March 20, 1809, established clearly her lengthy friendship with Jefferson and mentioned ties of blood through Jefferson's paternal line:

[Ann Craig to Thomas Jefferson]6Dear Sir

You will be surpris'd, I doubt not, on receiving a Letter from a very old acquaintance, Ann Craig, formerly of Williamsburg, who takes the liberty of addressing you. When you studied law in Williamsburg, you did me the honor to lodge in my house: I was then in easy Circumstances, but the fire in Richmond, the death of my Brother Doctor Pasture, and other misfortunes, this is far from being the case now; insomuch that I have been for several years, and now am, under the necessity of depending upon my relations for support. But from the death of several of my nearest relations, and others of them being in debt, so it is, that so little is rais'd for my support, that the Lady with whom I am plac'd (Mrs Markahm near Manchester) is but indifferently paid for my Board. Being thus, Dear Sire, very old infirm, and dependent, I avail myself of the privilege these give the unfortunate, to request the favor of a small annual contribution for the support of a needy relation, being Cousin german to your Father. my greatest wish is to be enabled by my Friends to return to my native place Williamsburg, and there to end my days.The above statement, Dear Sir, is but too true; but should you have any doubts on the subject, or wish for further information, I beg leave to refer you to my Friend Mr Edm'd Randolph, or Dr Turpin: and should you think proper to grant me any assistance, I shall ever retain a most grateful sense of the obligation.

I am Dear Sir with the greatest respect and consideration

your most obl hbl Ser

Ann Craig1

After much investigation, it is yet unclear to the author exactly how the Pasteurs were related to the Jeffersons.* Nevertheless, it can be assumed that a blood tie probably did exist and that Jefferson knew his Pasteur "cousins" well since he lodged with Ann and Thomas Craig while a law student (1762-1767) in Williamsburg.**

William Pasteur began a business for himself as an apothecary in 1760, about the same time that he married Elizabeth Stith. In 1775 Dr. Pasteur formed a partnership with Dr. John Galt which lasted until 1778 when he conveyed the lot, buildings, instruments and supplies to Dr. Galt. In 1779 the Pasteurs removed from Williamsburg to their farm in the country. Before this time, between 1772 and 1777, Pasteur had built his house on Francis Street which today is known as the Semple House. During these same years, Thomas Jefferson was a frequent visitor to Virginia's colonial capital:

| "1772 | April 14 - June 14 | in and out |

| October 13 - November 14 | " | |

| 1773 | March 5 - March 13 | " |

| April 10 - May 9 | " | |

| June 7 - June 11 | " | |

| October 12 - November 6 | " | |

| November 29 - December 4 | " | |

| 1774 | April 18 - June 16 | " |

| 1775 | March 28 - June 11 | " |

| 1776 | October 6 - December 31" | "*** |

At any time during his visits, Jefferson might have assisted his cousins, the Pasteurs, with the design of their new house, as Jefferson is known to have done for various friends and relatives.* There is no doubt that Jefferson was in touch with Dr. Pasteur during these years and before, for as early as 1768 Jefferson is known to have purchased a violin from Dr. Pasteur for £5.** On April 11, 1769, Jefferson "pd. at Pasteur's shop for gum mastic 1/3"***. On April 25, 1771, he "pd. Dr. Pasteur for a mop,"**** Later, in 1773, on May 7th Jefferson "pd Alexr Craig £ 21 - 12 - 4" and "pd Doctor Pasteur £ 1 - 10 - 3".***** On December 13, 1777, he visited Pasteur's shop and "pd. at Dr. Pasteur's for 2 lb bokea [?] tea £ 4 - 10"****** ; and a year later, on December 19, 1778, he "pd Dr. Pasteur in full 18/".******* Jefferson must have been one of Pasteur's last customers, for it was only a short time later that he sold out to his partner, Dr. Galt.

Having fully established ties of blood and commerce (and a very probable friendship), it is well to state briefly the architectural associations between Jefferson and the Semple House. As a preliminary statement, it can be said with little reservations that the Semple House, whether or not designed by Jefferson, is nevertheless a very Jeffersonian building. Page 8 Its plan, elevation, details, and design idiosyncrasies (i.e., the stairway) bear a great deal in common with Jefferson's work and there is a early drawing in the Collidge Collection by Jefferson which could well be an early study for the Semple House. This drawing and other Jeffersonian aspects of its design are discussed more fully in Chapter 4, under the Semple House.

Its plan, elevation, details, and design idiosyncrasies (i.e., the stairway) bear a great deal in common with Jefferson's work and there is an early drawing in the Coolidge Collection by Jefferson which could well be an early study for the Semple House. This drawing and other Jeffersonian aspects of its design are discussed more fully in Chapter 4, under the Semple House.

In addition to the Semple House, Battersea, and Brandon, there are other Virginia tripartite pedimented houses with important and provocative Jefferson connections. Mountain Grove (1803) in Albermarle County, not far from Monticello, is located on a road which Jefferson might have traveled en route to this country retreat, Poplar Forest. Mountain Grove was probably built by Benjamin Harris, "a man of great wealth, ... appointed a magistrate in 1791, and served as sheriff in 1815."* He married Mary Woods, daughter of Samuel Woods, and they had eleven children. Benjamin Harris was himself one of ten children of William Harris (1739-1788), Albemarle County, and Mary (nee Netherland), his wife. Jefferson, as a lawyer, undoubtedly knew Benjamin Harris (and the Woods family, one of the oldest in Albemarle County) while he first held public office, if not before. Although there is no existing correspondence between these two men, Harris is listed in Jefferson's Account Book, first on December 8, 1776, when the following was recorded: "pd Ben Harris for a gin for Colo. Coles 10/"** and again on September 18, 1799: "pd H. Cox for Ben Harris for 4 Cotton gins £ 6."***

Another connection between Jefferson and the Harrises, though somewhat tenuous, is nevertheless interesting. Mary Woods Harris' sister, Elizabeth Woods, married Benjamin Harris' nephew, William B. Harris, whose sister, Frances Harris, married Lewis Nicholas of Albemarle County (son 11 of Jefferson with the design of Bon Aire."* If it is true that Bon Aire is a Jefferson design, then there can be little doubt that he also designed Mountain Grove for Benjamin Harris and possibly some of the North Carolina "Palladian farm houses".

The Jefferson relationship in the Halifax area of North Carolina, although touched on in another section of this report (some Halifax - Virginia connections), will be more fully explored here. It is difficult to know the early history of the Halifax area since so few records have been published and so few histories have been written. It is not known when Jefferson first established connection in North Carolina and he is not thought to have ever visited there.** The Revolutionary War might have been the event in history that drew Halifax close to the leaders of Virginia, due especially to the important role the citizens of Halifax played during that conflict. At any rate, there are recorded letters between Nicholas Long of Halifax and Thomas Jefferson as early as 1781, these generally concerned with the war effort.

Jefferson knew at least one other leading citizen of Halifax, Willie Jones. Jones was one of the most influential politicians in the state and to quote James Iredell, Governor of North Carolina, "He lived sumptously, and wore fine linen; he raced, hunted, and played cards; he was proud of his wealth, and social position... He was a loving, and cherished disciple of Jefferson".*** During the Conventions at Hillsboro for the ratification of the national Constitution, on July 21, 1788, 12 "Mr. Jones quoted a letter from Mr. Jefferson."* This is the only known correspondence between these two leading figures of the day, and the document itself is not thought to exist.** It is indeed unfortunate that more is not known concerning Jones' apparent friendship with Jefferson, for the hose which he built for himself near Halifax, called The Grove, is very much in the Jeffersonian style and might well have been built from a sketch supplied by Jefferson. (See Appendix)

It is unknown exactly when The Grove was built, but it is thought to have been around 1773, although architectural evidence would suggest a later date. Regardless of its exact date of construction, The Grove did bear a striking resemblance to the Semple House, a building which probably predates it and may have been its prototype.

Although there is no proof of Willie Jones' ever having been in Williamsburg,*** it would seem entirely probable, as there was at this time a great deal of commerce between Halifax and Virginia. In 1771, an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette named Willie Jones as an agent in selling land on the Roanoke River (near Halifax) for the subscribers Robert Burwell & Nathaniel Burwell.**** Jones was himself an occasional advertiser in the Virginia Gazette. As early as 1766, he and his brother, Allen Jones, advertised land for sale which had belonged to their father*****; and in 1771 Willie Jones advertised for the return of a horse which had strayed from 13 "Mr. Timberlake's in Petersburg."* In 1777, he advertised his famous horse, Whirligig, at stud on his plantation on the Quankey.**

The most interesting connection between Willie Jones and Jefferson, his mentor, was made late during Jones' life. Martha Jones, Willie's daughter, married John Wayles Eppes (1773-1823), Jefferson's former son-in-law and cousin by marriage (Eppes had been previously married to the sickly Maria Jefferson.) Entered in Jefferson's account book on May 1, 1817, is the following: "inclosed to J. W. Eppes an order on Gibson & Jefferson for 26 D. to pay for a barrel of Scuppernon wine bot for me by Mr. Burton of Halifax, N.C."***

It is difficult to say whether or not Jefferson actually designed Battersea, Brandon, the Semple House, Mt. Grove, Bon Aire, or any of the many North Carolina houses which are so similar in style; but the odds seem to be greatly in favor of such a supposition. It is hoped with the monumental effort being made currently to discover, edit, and properly catalogue the seemingly infinite number of Jefferson papers, some document will be uncovered to prove that Jefferson was, in fact, the creator and propagator of the Palladian farm house style in America.

An unidentified drawing from the Coolidge Collection which is thought to have been made by Jefferson about 1789.

An unidentified drawing from the Coolidge Collection which is thought to have been made by Jefferson about 1789.

Mt. Grove, Albemarle Co., Virginia This plan has a great deal in common with the unidentified drawing above.

Mt. Grove, Albemarle Co., Virginia This plan has a great deal in common with the unidentified drawing above.

CHAPTER 3

Some Halifax - Virginia Connections

The apparent climax in popularity of the tripartite pedimented house in America was reached during the Federal Period, not in Virginia as might be expected, but in North Carolina, especially in the Halifax County area. The "Palladian farm house" style did not die out in Virginia after the Revolution, but it apparently never enjoyed the popularity it had in North Carolina during this time. An exact, documented explanation for the popularity of this style in North Carolina has yet to be found, although several factors seem to have contributed to this phenomenon. First, there were many Virginia connections among Halifax people, especially through family ties. Second, the prosperity and growth of the Halifax area was considerable during the later part of the eighteenth and first years of the nineteenth centuries, which encouraged an appetite for things fashionable among the prosperous landowners.* Third, though there is no proof, Thomas Jefferson may have had some architectural influence among his friends in Halifax (see Some Jefferson Connections). Before discussing Virginia-Halifax connections in particular, it is well to establish a few pertinent facts about the area and its early history.

Halifax County, named in honor of Charles Montague, Earl of Halifax, is located in the northern portion of North Carolina, its most northerly point being only six miles from Virginia. The Roanoke River skirts its northeastern border and separates Halifax from Northampton and Bertie Counties. Fishing Creek defines its southern border, separating Halifax from Edgecombe, the county from which Halifax was formed in 1758.**

2"Halifax County, and particularly Halifax town, was for a number of years the political center of North Carolina. The ancient borough was in reality the Capitol of the State during and soon after the Revolution. There, many of the officers of the Commonwealth lived much of the time, and there, most of the records of state were kept. Of course when the seat of government was removed to Raleigh, everything pertaining to State affairs was removed to that place also. Halifax, therefore, lost much of its influence. Even after that, however, the town was a center from which radiated social, literary, and economic forces that were felt in remote portions of the State."*

The English visitor, Smyth, in 1774, noted that Halifax was "a pretty town" to which "sloops, schooners, and flats, or lighters, of great burden" came up the stream which was "deep and gentle." He said that Halifax enjoyed "a tolerable share of commerce in tobacco, pork, butter, flour, and some tar, turpentine, skins, furs, and cotton" and that there were "many valuable fisheries at, or in the vicinity of Halifax."**

Halifax was the main distribution point for merchandise brought up the Roanoke by sailing vessels, from Norfolk and intermediate points. By the same token, Halifax exported a great deal of products to Norfolk, especially flour and meat. In addition to trade by the Roanoke, a large contingent of wagons and carts carried wheat, tobacco, and cotton overland to Petersburg and Richmond. Much of the economic and social life of Halifax revolved around the horse. Willie Jones was an enthusiast and had his own race track at The Grove, his "Palladian farm house" on the Quankey. Through racing and breeding, Jones and other equestrian North Carolinians were in fairly close contact with Virginia.

3The early settlers of Halifax County were primarily Virginians of English and Scotch descent,* whose ties of kinship and fraternity with Virginia were never completely broken (as is indeed true today). Of the towns in Tidewater Virginia, Norfolk, Petersburg, and Richmond probably had the closest connections with Halifax, although Williamsburg seems to have its share of ties. Although there were probably more, at least one Williamsburg citizen, John Geddy, migrated to Halifax. John was the brother of James Geddy of Williamsburg (sons of James Geddy), and, like his brother, was a silversmith by trade.** It is probable that another Halifax family, the Pasteurs, were related to, or descended from, a Williamsburg family of the same name. The 1790 Halifax census lists three Pasteur families, those of Thomas, James, and Charles Pasteur.***

Of Charles Pasteur, the most is known. His name is entered in the account book of Richard Charleton, the Williamsburg wigmaker in 1770 and 1771 as "Docr Charles Pasteur (North Carolina)"****. He (along with the before-mentioned Willie Jones and John Geddy) is again mentioned 4 in a letter, dated October 19, 1784, from James Iredell to his wife: "There has been the most shocking mortality among the children here ever known. Willie Jones has lost two, Dr. Pasteur one; ... Geddy in the course of a fortnight lost his wife, two of his children, and a grandchild..."* From these sources, it is known that Pasteur was a doctor who probably visited Williamsburg at least twice, and was a citizen of some importance (the fact that he would be mentioned by James Iredell in a letter to his wife would indicate that the Governor and his wife knew the Pasteurs to some extent). The Halifax Pasteurs could have been descended from "Charles Pasteur and sa femme"** who immigrated with Jean Pasteur in 1700 aboard the "Nassau", about whom very little is known.*** The use of the name "Charles" by a later generation gives a bit of credence to this speculation.

Citizens of Halifax quite often advertised in the Virginia Gazette between 1761 and 1777, the majority of which were concerned with the sale of Halifax livestock, especially horses, and real estate. According to tradition, it was not unusual for the sons of prominent Halifax citizens to attend the College of William and Mary.****

5The few Virginia (particularly Williamsburg) connections with Halifax which have been uncovered by this author are undoubtedly only the beginning of what might be found; but due to the lack of published Halifax records, further research is impractical at this time. From all indications, it was through the Halifax-Virginia relationship that the "Palladian farm house" style of architecture spread southward to North Carolina, but whether by family connections, an unknown carpenter/builder, or by Jefferson himself is yet a mystery.

CHAPTER FOUR

The following is a survey of the tripartite pedimented houses under consideration in this paper. The buildings are grouped geographically by state and are in sequence from early to late, as well as can be determined. Virginia buildings, for the most part, comprise the first group, the exception being Whitehall in Maryland. The second group includes those North Carolina houses visited by the author, among which are the best of their type but in no way presumes to include them all.

TAZEWELL HALL

Location: Williamsburg (now reerected in Newport News), Va.

Date: circa 1765

Present Owner: Mr. and Mrs. Lewis A. McMurran, jr.

Plan: Type I

Type of Construction: Wood frame

Exterior: Tazewell Hall is actually a 7-part house, but, like Battersea and Brandon, its main body is tripartite having a central two-story pavilion and one-story wings. The similarity with Brandon is extraordinary -- both buildings have similar (but slightly awkward) proportions, identical (and atypical) hipped roofs, and the same chimney placement in the main body. But unlike the other 7-part building, and indeed all of its type in Virginia (except Fortsville), the center pavilion is not fully expressed; i.e., not lying in a vertical plane different than that of the wings.

Interior: The interior of Tazewell Hall is spectacular with its very monumental entrance salon which rises the full 2-story height of the center pavilion; a unique space seen again only at Whitehall. These rooms are representative of the ideal in Palladian architectonic spatial planning.

Notes: Though somewhat forgotten by architectural historian[s], Tazewell Hall's importance in the mainstream of American architecture cannot be overstated. It, wit[h] Page 2 Whitehall, ushered in the Palladian farm house style which was to become so popular in the years around the turn of the 19th century. Tazewell Hall was built by John Randolph, the Tory, during the 1760's, greatly altered in the 19th century, and now put back in its original form in Newport News, Virginia.

John Randolph (1727/8 - 1784) married in 1751 Ariana Jenings; daughter of Edmund Jenings, the Secretary of Maryland under Governor Sharpe. Financially, this seems to have been a very fortunate union for young Randolph who had only recently returned from his schooling in England. From a document dated January 31, 1786, it is known to what extent Ariana's dowry played in the building of Tazewell Hall:

"The house she Claims was built upon her late Husbands Land, Says in Order to build it She gave up her right to the Money settled on her on their Marriage amounting to £1700 Sterling besides which she consented to Sell a number Negroes which her Father had given her. She does not know how many. Mr. Randolph valued it at £ 4000." "The House for which Claim is made was built with Mrs. Randolph's Money left her by her Father. "She was considered as having brought Mr. Randolph £ 10,000 Sterling."*Unhappily the exact date for the building of Tazewell Hall is not known, but it is thought to have been around 1765, which would coincide with the supposed Page 3 date of Whitehall. The similarity in style between these two revolutionary buildings, coupled with the Jenings-Randolph connection between Annapolis and Williamsburg, would suggest that both buildings might have shared the same designer or pattern book prototype, or that one was the inspiration for the other.

WHITEHALL

Location: Near Annapolis, Maryland

Date of Construction: c. 1765

Present Owner: Mr. and Mrs. __________ Scarlett

Plan: Type I

Type of Construction: Brick

Exterior: The exterior of Whitehall is quite advanced for its time in America and is important as an innovator of its style: first, by having a tripartite composition with a two-story pedimented central block and one story wings; and, second, by initiating the use of the heroic portico in this country. Whitehall's portico, with its great fluted Corinthian columns and superbly carved capitals, is truly remarkable and unique among the buildings of its type in America.*

Interior: Whitehall's plan is as direct as possible -- a perfectly symmetrical salon occupying the full width, depth and height of the pedimented central block (no stair or fireplace); with one room flanking it on each side. The salon (approximating a cube) is richly ornamented with Page 2 elaborate woodwork and sumptuous rococo embellishments. The richness of Whitehall among the houses of its type is unique, due in part to the purpose of the building and to its English-trained designer.

Notes: Whitehall was built by Governor Sharpe of Maryland as a pavilion for entertaining guests on excursions across the river form Annapolis. It was probably designed by William Buckland (1734-1774), an English-trained immigrant craftsman-architect, who designed some of colonial America's most sophisticated and high-style buildings and interiors. R. R. Beirne and J. H. Scarff in their book, William Buckland, make the following statements: "Just what part Buckland has in the execution of Whitehall is uncertain. The present owner has done considerable research on the subject and owns unsigned plans. He feels that while another than Buckland may have drawn these, the latter was responsible for carrying out the joinery. Most assuredly the interiors show great competence and familiarity with the best Georgian precedent and are not unlike the work done by Buckland in other Annapolis houses. The strongest motive for crediting him with the woodwork of Whitehall is the fact that no other man of the period capable of executing the design is know Governor Sharpe visited and hunted with George Mason at Gunston Hall [a house with Buckland interiors], so it is likely that he was acquainted with Buckland."* Page 3 Buckland's training in England readily accounts for Whitehall's avant garde conception, but its prototype -- whether an English building or pattern book -- is yet uncertain.

[Whitehall - 2 Drawings]

[Whitehall - 2 Drawings]

BATTERSEA

Location: Petersburg, Virginia

Date: circa 1760

Present Owner: Mr. and Mrs. Russell S. Perkinson

Plan: Type II, with connected terminal buildings, thus a five part scheme.

Type of Construction: Brick (now stuccoed)

Exterior: Battersea's exterior was altered some fifty years after its building, but with little detriment to its original design which is quite close to that of Brandon. The present Palladian windows replace pairs of windows (see plan) It is probable that Battersea originally had a two-tiered porch on its central pavilion, which has a hipped roof instead of a pedimented roof.

Interior: The well-known Chines Chippendale trellis stairway at Battersea is the most distinguished feature of its interior, being based on Gibbs' Rules for Drawing.

Notes: Though Battersea is a five-part composition, the central portion of the building bears much relationship, both in plan and elevation, with the typical Palladian farm house in America; and is certainly one of the most distinguished and sophisticated examples to be seen. Its builder was John Banister, a friend of Thomas Jefferson, and his wife, Martha Bland, was a relative of Jefferson through the Blands and Randolphs.

[Black and white photograph and floorplan - Battersea]

[Black and white photograph and floorplan - Battersea]

BRANDON

Location: Prince George County, Virginia

Date of Construction: Built 1789 by Wm Curtis

Present Owner: Mrs. Robert W. Daniel

Plan: Type II, with terminal buildings and enclosed connections -- thus, a 7-part composition.

Type of Construction: Brick

Exterior: The design precedent for Brandon would seem to be Plate III of Morris' Select Architecture, with few alterations. The center three elements, though without pedimented roofs, are nevertheless quite close in design to the usual tripartite pedimented houses in Virginia and North Carolina.

Interior: Unlike most houses of this group, Brandon has a great deal of interior paneling, all quite well designed in the Palladian style. The present monumental stair is a later addition which replaces an earlier one which was most likely located in a narrow cross hall, as at Battersea.

Notes: Nathaniel Harrison built Brandon in the last quarter of the 18th century, and it is traditionally thought to have been designed by Thomas Jefferson. There is no documented proof of Jefferson's authorship, although he was a friend of Harrison (and a groomsman in his wedding in 1765), and it is known that he owned a copy of Select Architecture.

[Photograph - Brandon, Prince George County and Two Plates]

[Photograph - Brandon, Prince George County and Two Plates]

SEMPLE HOUSE

Location: Williamsburg, Virginia (Block 2, Colonial Lot 257)

Date of Construction: 1772-1777

Present Owner: The C. W. F.

Plan: Type I, with later additions. (now removed)

When examining the plan of the Semple House, or its now-famous façade, this building stands out as being a design well in advance of, or in rebellion against, the native or typical Williamsburg houses. For this and other reasons, the Semple House has been traditionally attributed to the hand of Thomas Jefferson. The ground floor arrangement includes a large, almost square center hall, or entrance salon, which is flanked by an equally large room to the west and by a smaller room and stair hall to the east. Two large chimney breasts flank the central room, becoming an integral part of the walls which divide this space from the end rooms. Two small second story bedrooms and a hall occupy the space over the entrance salon and within the upper portion of the pedimented pavilion.

There is ample precedent for the Semple House plan. Similar room arrangements are seen at Whitehall and Tazewell Hall, both of which predate the Semple House by about a decade. (The plans of Brandon and Battersea are certainly related.) Thomas T. Page 2 Waterman stated that the first study for Monticello (before 1770) "parallels the design of the Randolph Semple House to such a degree that there can be no doubt that they are by the same author."* In addition to the American precedents and attributions, there are English pattern book designs from which the Semple House plan could have evolved. Plates from William Halfpenny's The Modern Builder's Assistant and other appropriate pattern books are possibilities, some of which are reproduced and discussed in Chapter 1.

The Semple House seems to be based on both English and American precedent. It is difficult to know to what extent English pattern books may have dictated its design; for if Jefferson did in fact design the Semple House, it would be [a] more Jeffersonian building [than a] literal copy of some pattern book design, even if it were eclectic. Neither Jefferson, nor any other creative person, could ever allow himself to become a slave to a pattern book, no matter how much he admired his master. This in a nut shell is the problem faced with trying to make pattern book attributions to existing buildings.

[Monticello drawings]

[Monticello drawings]

Besides the previously mentioned "first scheme for Monticello" which Waterman feels has so much in common with the Semple Hose plan, there is yet another drawing which has far more significance. (See following illustration) This rough sketch by Jefferson in the Coolidge Collection has no watermark and therefore cannot be accurately dated, although authorities believe it to date around 1770-1771 and to be an early scheme for Monticello.* Although there is little evidence on which to base this assumption, it could be valid. With even less speculation, this unidentified sketch could be seen as a study for the Semple House. Noticeable similarities are:

- (1)Arrangement of rooms.

- (2)Two-story central pavilion with flanking one-story wings.

- (3)Stair located in a wing.

- (4)Center room is 20 feet by 20 feet.

- (5)Depth of wings is 18 feet.

- (6)Projection of center pavilion beyond the wings is one foot.

- (7)Chimneys flank the center pavilion.

[Study of Monticello floorplan and Semple House Plan]

[Study of Monticello floorplan and Semple House Plan]

The stairway of the Semple House, tucked away inconspicuously as it is behind the east chimney, gives rise to unending speculation and controversy. First of all, this stairway is totally unlike any other in Williamsburg; second, its location is unique; and third, it would have been almost unusable due to the lack of head room toward the apex of its precarious ascent.* It is true that the Pasteurs had little use for a large house since their only child died quite young, but this alone does not explain the limited accessibility f the second floor rooms. Any practical rationalization seems unreasonable, thus it might well have been purely a matter of design.

Might the architect have desired to combine the best features of contemporary Virginia Palladian farm houses while eliminating certain undesirable or impractical aspects -- that is, to have second floor rooms over the entrance salon, but without introducing such non-Palladian features as a stairway or cross-hall within the space reserved for the entrance salon?** If this is a true assumption, it would be a totally aesthetic consideration on an academic level well above that of the average eighteenth century architect/builder.

Page 5Here again evidence would point to Jefferson, and for two reasons. First, a similar stair and location is seen in the before-mentioned Jefferson drawing in the Coolidge Collection; and second, Jefferson traditionally de-emphasized stairways in his plans, often to the detriment of those who had to use them.

Between 1806 and 1823, a large addition was made to the rear of the Semple House under the ownership of the Semple family, who bought the house around 1801 and whose name it bears today. It is interesting to note that in every known tripartite Type I plan house in North Carolina and Virginia, almost identical additions were made after they were initially built, incorporating a cross-hall and a large room behind. (See Fortsville, The Grove and The Hermitage).

Type of Construction: Wood frame.

Exterior: The Semple House has long been famous for the beauty of its principle façade. The central pavilion is two stories in height, the lower floor being quite high with tall windows, and the upper correspondingly low with windows which are almost square.* The handsome center door is richly paneled and protected by a very fine pedimented porch supported by Doric columns on pedestals.

Page 6The corresponding entablature with its pulvinated frieze, rich guiloch*, modillions and dentils is unusual when used in conjunction with the Doric order. In fact, this is the only original order of its type known to the author.** The central pavilion is covered by a pedimented roof, the tympanum containing a circular window. The cornice is rich but delicate, with both modillions and dentils. The wings, which are one story in height, continue the fenestration of the main block and are covered by pedimented roofs at right angles to that of the central pavilion.***

The whole effect is one of great monumentality, formality, and richness, especially for a building of such commonplace dimensions. It is possible that it was this aspect of the Palladian farm house style which appealed to the well-to-do planters and city folk alike of Virginia and North Carolina.

Page 7Interior: Without question, the two outstanding rooms of the Semple House are the entrance salon and the drawing room to the west. The rich woodwork of the drawing room, which was probably based on pattern book designs, gives this room an importance beyond that of the salon or east dining room, and is considered by some to be one of the finest colonial rooms in Williamsburg. The proportioning of the walls into its pedestal base, wall, cornice is similar to that suggested on page 55 of William Pain's The Builder's Companion (third from the left). From this same pattern book, page 77, is the probable prototype for this room's mantel with its carved frieze in a diaper pattern. The wainscot consists of flush horizontal boards which break out beneath the windows forming pedestal bases. The cornice consists of a crown mold, fascia, modillions, and a full bed mold which is an unusual and fine feature of this room.

The entrance salon, also a finely proportioned room lacks the richness of detail which the drawing room enjoys. This may be due to the fact that this room was retrimmed at a later date. The dining room (east wing) is quite simple and the smallest room on the man floor due to the insertion of a narrow passageway between it and the entrance salon. This passageway acts as a connecting link between the salon, dining room, second floor rooms via the stair, and the garden to the rear. The center portion of the passageway is covered by a low masonry Page [8] arch between the chimney breasts of the dining room and entrance salon, which accommodates the flue running from the dining room fireplace diagonally to the east chimney stack. This fascinating arrangement is most unusual and is yet another demonstration of the lengths to which the designer of this house went in order to achieve the Palladian ideal.

Notes: The Semple House is unquestionably the most aesthetically satisfying of all tripartite pedimented houses in America, even though there are others which have slightly more academic or sophisticated aspects. As well as can be determined, this house was among the first of its type to be built in America, following Whitehall and Tazewell Hall a decade later. Little is known concerning the building of the Semple House but it is thought to have been built by Dr. William Pasteur, Williamsburg apothecary, between the years 1772 and 1777.*

The Semple House has long been subject to much praise and conjecture, concerning its design and possible designer. Both its plan and elevations are decidedly foreign elements in the milieu of colonial architecture of Williamsburg, which suggests that its designer was an outsider, but one who was well acquainted with the work of Andrea Palladio. As yet, there can be formed no proof of this person's identity, although there is much reason to suppose it was Thomas Jefferson. (see Some Jefferson Connections.)

MONTICELLO

(first building)

Location: near Charlottesville, Va.

Date of Construction: c. 1771

Present Owner: Thomas Jefferson Memorial Foundation

Plan: Type II, with modifications and additions

Type of Construction: Brick

Exterior: Jefferson's drawing of Monticello's first façade (1771), unlike its ultimate form, clearly reveals its relationship with other tripartite pedimented houses of the period and those which followed. Though the wings are two story, they read more as one story elements due to the heavy cornice and the greatly shortened second story windows. The central pavilion is covered by a pedimented roof which extends out from the body of the building and is supported on the front by a two-tiered portico of superimposed Doric and Ionic orders. (A similar portico and roof arrangement is seen near Milledgeville, Georgia at Mount Nebo.)

Notes: The plan of Monticello as it was first built is quite similar to Type II - each element is in its usual place, though modified in some cases. Jefferson was obviously so interested in symmetry, articulation, and the creation of vistas, that his plan became quite cramped and somewhat awkward. Nevertheless, this was the house he built for his bride.

[Drawing and plan of Monticello]

[Drawing and plan of Monticello]

MT. GROVE

Location: Near Esmont, Albemarle County, Virginia

Date of Construction: 1803-04

Present Owner: Mr. O. E. and Mrs. M. W. Lawrence

Plan: Type II

Type of Construction: Brick

Exterior: The piano nobile of Mt. Grove, like that of its neighbor, Bon Aire, is raised well above the ground level to accommodate a full basement, thus creating an even more monumental effect. It would appear that Mt. Grove was never fully completed, for, from all indications, neither a portico nor even a stoop was ever constructed in conjunction with the front entranceway; although it seems certain that a portico was intended. This assumption is predicated on the lack of a center second story window which creates a great expanse of wall above the entrance door, a space which the upper part of a gabled portico would ordinarily occupy. The cornice at Mt. Grove is quite rich but a bit heavy for its date although the Albemarle County area has a tradition of heavy cornices due to the Jefferson influence on local builders.

Interior: Mt. Grove's interior trim is among the best of its group, and quite advanced in style for its time. The drawing room is outstanding, a large, well-proportioned room having painted and grained wainscot, chimneypiece, and over mantel. The central portion, Page 2 field, of the pilastered over-mantel is not grained, but has an interesting and unusual strippled background with painted swags and cascades at the top of the panel. The library, occupying one wing flaking the central pavilion, is also a fine room, but of a smaller size and a lower ceiling height. The outstanding feature of this room is the treatment of the fireplace wall, where a pair of deep built-in book cabinets or buffets with glazed doors above and solid doors below flank the chimney breast. The chimney pieces and over-mantel is similar in design and finish to that in the drawing room. Another fine point of the interior is the doors, which were painted and grained to simulate richly figured wood with the added enrichment of penlined panel fields.

Notes: It is thought that Mt. Grove was built by Benjamin Harris*, "a man of great wealth, ...appointed a magistrate in 1791, and served as Sherriff in 1815. He married Mary, daughter of Samuel Woods, and had eleven children."** Benjamin Harris was one of the 10 children of William Harris of

Albemarle County (1739-1788) and Mary, (nee Netherland), his wife. Mary Woods Harris' Through marriage, both Mary and Benjamin Harris were related to Wilson Cary Nicholas of Albemarle County, a close friend of Thomas Jefferson who is known to have designed a house (about which nothing is known) for him, which is mentioned in a letter form Jefferson, dated August 19, 1796.** This connection plus the fact that Jefferson knew the Woods and Harris families gives more credence to the theory that Jefferson might have in fact designed Mt. Grove (and Bon Aire, its sister house).*** Though there is no proof of Jefferson's authorship of Mt. Grove, it is nevertheless quite Jeffersonian in design, and not unlike the first form of Monticello.

[Mountain Grove Drawing]

[Mountain Grove Drawing]

[Photograph and floor plan - Mountain Grove]

[Photograph and floor plan - Mountain Grove]