Coopers

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 316

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

Coopers

Coopers.

The word cooper is apparently of low Dutch origin. The modern Dutch word for cooper is cuper. In medieval latin cuparius, cuperius, was formed from cupa, a cask. The word is not an English derivative of coop, which, so far as appears, has never had the sense of 'cask'. One can find in the 15th. century various spelling of the word, such as, couper, cowper, cowpar, (Oxford Dictionary ).

The craft is mentioned in the bible and was known in Ancient Egypt. By the close of the Middle Ages the barrel was the standard means of packing, and the craft was widespread. On board ships, almost everything was towered in casks, and the coopers continued to be important members of the ship's crew until the mid-19th century. In British ports it was customary to load ships with a large number of roughly-shaped staves. On the outward journey to some far corner of the globe the coopers would be busily engaged in making barrels, in which various cargoes would be stored for the return voyage.

In England the coopers made a variety of items from butter churns to brewing vats. The Coopers' Company in England received its Charter of Incorporation in 1501 and was formed along the lines of other craft gilds of the period.

Coopers are considered as among the west highly skilled of all craftsmen, since they work to no written measurements or patterns, and to make a barrel of a specified diameter and capacity they depend on long experience and instinct alone. They were often classified as to the type of work they performed or the type of cask they fabricated.

Dry-coopering is the making of barrels for holding non-liquid substances, such as flour, sugar or fish. It is considered the least specialised category of the craft. For making this type of barrel the cooper mainly uses fir staves , bound together with ash or hazel hoops. ii The staves themselves are less tightly edged together than in wet coopering, and the finished barrels are far less bulged.

White coopering is that of making pails, butter churns, ash tubs, and a variety of other utensils for dairy and household use. The main material used by the white cooper was oak, but for dairy utensils he used a great deal of sycamore.

By far the most important, of the category of cooperage is that of the wet cooper who makes barrels to hold liquids. His work is more exacting as he must make and mount his staves so they will afford the necessary tightness.

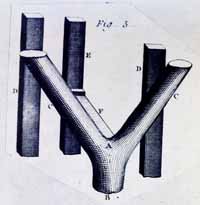

It appears that in large cooperages in Europe the cooper purchased his staves and headings already prepared. The write ? writes on cooperage in Descriptions des Arts et Metiers mentions that they were purchased elsewhere and Edlin in Woodland Crafts in Britain states that "Barrel staves have been imported to Britain for so long and in such large quantities that the cleaving of them from freshly felled oak is now rarely practised here." He mentions that in the great forest of Troncais, in the Allier Department of central France, the art of making staves is still carried on, and that tradition asserts it has been carried on since Roman times. Mr. Edlin's book was published in 1949 and he writes that he had visited this place. His description of the first process is interesting: The tree used is oak, cut from trees averaging three feet in diameter. The great logs are first of all cross-cut to length and then cleft into segments with wedges and a mallet until the pieces are small enough to handle. Each trimmed segment is then carried to a Y-shaped frame or break, composed of the natural fork of a tree and standing on three posts within a rough woodland shelter. (see illustrations A and B, pp. 26-27) A tool resembling the English froe and having a handle two-and-a-half feet long, is then used to cleave the segment into two or more staves. (see iii. tool section, page 32, fig. 11.) The description that follows is similar to that included in this report.

Coopering remains one of the few crafts where hand methods have not been superseded by machinery, and where the methods have not changed substantially for centuries.

Manufacturing of staves, hoops, and headings in Virginia.

Pipe-staves1 were manufactured in Virginia as early as 1607. In 1650, one writer calculated that a man was able to make annually fifteen thousand pipe-staves and clapboards, which could be sold in the Canary Island for 20 pounds sterling a thousand and that the labor of one man could yield him 60 pounds per annum at the lowest market.2

Another account, probably written in the 1740's, states that shipmasters, when they were unable to obtain a full lading of tobacco, carried out pipe-staves, clapboard, walnut and cedar timber.3

The manufacturing of staves, headings, and hoops, especially of staves, became a large business of the Colony. By mid-eighteenth century, in February 1752, an act was passed to regulate the size and dimensions of staves, headings and shingles, intended for exportation to Madeira, and the West Indies. Dimensions of pipe-staves, exported to Madeira, were to be four feet, eight inches long, and four inches broad, and one inch thick, on the heart edge. All hogshead staves were to be three feet, six inches long, four inches broad, and three quarters of an inch thick. Their heading was to be two feet, eight inches long, seven inches broad, and one inch thick, upon the heart edge. All of these staves and headings were to be clear of sap.

To enforce these regulations one or more persons were to be appointed annually in the month of August or September in every county to act as viewers of all staves, headings, and shingles, intended for exportation. They were required to take an oath to uphold their duties and were to view the casks at the landings from which these commodities were to be shipped. v. A certificate was to be issued by them to the party requiring the viewing as to the number of casks he had examined and passed, and of the kind of timber they were made of. This certificate was then turned over to the Master or Mate of the ship in which they were exported.1

The Virginia Gazette published at various times the ships entering and clearing the various ports and the cargo they carried. The amount of staves and headings listed in the Gazette of 30 September 1737 affords us an idea of how great this product had grown: From April 16 to 26, 1737 three ships clearing for London carried a total of 12,035 pipe, hogshead, and barrel staves, and headings.

From the Upper District of the James from 25 March 1745 to 29 June 1746, a little over a year, 231,073 staves were exported from out of the colony. This excludes those exported to the Lower District of the James. Five ships clearing out of Hampton in 1745 carried 25,750 staves, and 3,700 headings. Nine ships clearing out of the York River in the same year had 42,698 staves and seven ships out of the Lower District or the James carried 60,959 staves, 13,046 headings, and 500 hoops.

Twenty years later the records reveal that between the 25 October 1763 and 25 October 1766, a three year period, a total of 1,736,593 staves and 13,200 hoops were exported from the Upper District or the James River!

The records also reveal that staves were imported into the Colony. One list of imports from the 25 March to 29 September 1745 lists a total of 16,300 staves imported to the Upper District of the James River. It is interesting to note that one of these ships came from Maryland. Why the colony imported staves we do not know. Perhaps these imported staves were in the rough and finished here for export or perhaps they were purchased by merchants with the idea or exporting them from here.

vi.The prices for various types of staves manufactured in Philadelphia was printed in the Gazette in 1738 and listed by the thousand: pipe staves, 5 pounds; hogsheads, 3 pounds, five shillings; and barrel, 40 shillings.

In checking through the York County inventories only one account of staves on hand was found. In the inventory of Mathew Tuell, Carpenter and Jointer of Williamsburg, who died in 1775 is listed 104 pipe staves. He also had one empty hogshead, 2 sets of small fellows, a set of iron hoops, 1 coopers adz, 1 coopers drawing knife, 2 axes, 1 whip saw, 1 cross cut tenant saw, and 600 feet of plank.1 This lack of staves in inventories cannot be explained; perhaps they were immediately sent out upon completion. The inventory is revealing however, in that a carpenter and joiner made staves. This was probably true of a number of craftsmen who worked in wood.

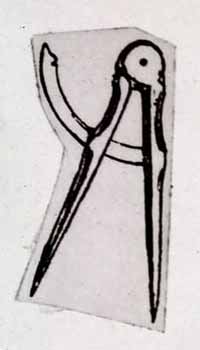

Tools for cooperage were advertised at various times in the Gazette. The Purdie and Dixon issue of 25 July 1766 contains a good list of cooper's tools to be sold in Norfolk: Cooper's adzes, cooper's axes, jointer and coopers irons, carpenters and cooper's bits, cooper's vices and tools, compasses, augers, gimlets, drawing knives.

No doubt many of the plantations had their own cooperage. The inventory of the estate of Nathaniel Harrison, Planter, in 1728, listed the Shop Barn as containing Cooper's, Carpenters, Wheelwright, &c. tools. The list had: 1 pr. coopers compasses, 2 froes, 4 drawing knives, 1 large bung borer, 2 hollowing knives, 2 joynters small, 2 heading knives, 3 coopers adze, 3 do axes.2

The need for tobacco casks in Virginia

The early development of tobacco as the great wealth of the Colony led to the need for casks to export it and for coopers. This soon led to the necessity of regulating the size and manner in which these casks were to be constructed, and from time to time various acts were passed by the Virginia Assembly.

To encourage coopers an act was passed in October 1646 which slated that no person was to deal for casks except with the coopers or their employees, and any debts that had been contracted for such work before this act were not to be recoverable.1 However, for reasons unknown, this act was repealed in November 1648.2 Perhaps there were not enough coopers in the colony at this time to meet the growing demand for casks and therefore they had to be made by others.

One can visualize these early tobacco casks, probably of various sizes and hurriedly made by inexperienced workers. Imagine a shipment of tobacco on the wharf and the ship master preparing to load them aboard: the difficulty he must have encountered when he had to record the weight of each different cask and the difficulty he must have had in loading them aboard! This may be the reason for the complaint of the Masters and Merchants of ships in 1658 for the "incertainty and extraordinary size of caske, which hath bin very much prejudicial to them, that a certaine size of all tobacco caske of Virginia hhds. shall be as followeth, vizt, ffourtie three inches in length and the head twentie & six inches wide with the bulge proportionable;". A heavy penalty of 3000 pounds of tobacco was imposed viii. on the person who made a cask to exceed this size or made a cask of unseasoned timber. The latter type made cask was to be ordered burned.1 This act was again enacted in March 1662.2

Apparently the size and construction continued to be of concern for in October 1705 an act was again passed that required all coopers or other persons intending "to set up tobacco hogsheads," to go before a Justice of the Peace in the county he lived and to take an oath that he would not willingly set up any tobacco hogsheads of a larger size than was proscribed by law. Each hogshead that he made was to be tared with a marking-iron or branding-iron with the true weight and was to be marked on the bulge and head of the hogshead together with the first letter of his "proper name and sir-name."3 Those persons who were employed by him were also to obtain certificates and to be subject to the same regulations. If any cask was of greater size or was made of less seasoned timber or staves, thinner than before directed or that was not tared with their just weight or made before a certificate was obtained the person making such a cask was to forfeit the sum of 500 pounds of tobacco. The act stated that "The tobacco cask was to be made of dry and well seasoned timber, and which hath been hewed three months at least before the setting up;4 and shall be set up in strong and substantial hoops; the staves shall be in length forty-eight inches, and noe more, and at least one third of an inch in thickness, on the thinness edge thereof; the size of the head on the inside shall be thirty inches in diameter, and no more."5

ix.As the Colony developed and grew and other products were exported in casks we find laws regulating the size and manner of constructing such barrels. In November 1760 an act was passed regulating the size and manner of constructing, barrels for tar, pitch, or turpentine. The heads and bulge were to be round, and the heads were not to exceed one inch and a half, nor to be less than one inch thick, the staves were to be of an equal length, and not less than three fourths of an inch thick, and no sap-pine timber was to be in the barrels made for turpentine. The barrels were to be well bound with good hoops, at least two thirds of their length, and were to contain thirty-two gallons and a half, wine measure, at least. This same act regulated the size of barrels for beef or pork. They were to be made of good white oak timber, well seasoned, and clear of sap, and were not to be less than three fourths of an inch thick; and every cooper or whoever set up any such barrels was to stamp or brand them as directed.1

Again in October 1776 an act was passed stating the duties of coopers who set up barrels for pork, beef, tar, pitch, or turpentine. Barrels for pork and beef were to be made with good strong well-seasoned white oak timber, clear of sap, and not less than five eights of an inch thick, tight, and well hooped with twelve hoops at least.

Barrels for turpentine were not to be made of sap pine timber, and were to be hooped two thirds of their length.

Every barrel for pork or beef was to contain from twenty nine to thirty one gallons each, and every barrel for tar, pitch, or turpentine, thirty one gallons and a half at least, with the name of the cooper or the name of the master, servant, or slave stamped or branded on every barrel. A penalty was imposed of 2 shillings and 6 pence for every barrel made contrary to this act.2

Cleared out of Upper District of James.

| Date | Ship and destination | staves | headings | hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 10 | Ship Duke of Cuberland to Bristol | 5,500 | ||

| 10 | Ship Carteret to Lower District | 20,000 | ||

| 17 | Ship Betty to Glasgow | 6,000 | ||

| June 17 | Brig Leob to Glasgow | 5,500 | ||

| 17 | Snow Mary & Betty to Whitehaven | 3,000 |

| Date | Ship and destination | staves | headings | hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| July 4, | Ship May to Glasgow | 9,000 | ||

| 10 | Ship Speedwell to London | 7,000 | ||

| 10 | Ship Molly to Lower District | 4,200 | ||

| Aug 5 | Ship Elizabeth to Glasgow | 10,000 | ||

| 11 | Ship William to London | 3,500 | ||

| 16 | Ship True to Brison to Liverpole | 1,000 | ||

| 21 | Ship Brothers to Whitehaven | 3,500 | ||

| 21 | Snow Vernon to Whitehaven | 4,000 | ||

| Aug 26 | Ship Jenny Galley to Lower District | 10,200 | ||

| 26 | Ship Happy to Whitehaven | 5,000 | ||

| 29 | Ship Restoration to London | 12,000 | ||

| Sept 5 | Ship Albemarle to London | 5,000 | ||

| 21 | Ship Friendship to Glasgow | 9,000 | ||

| 26 | Ship Susannah to Lower District | 6,000 |

| Date | Ship and destination | staves | headings | hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct 1 | Ship Christian to Greenock | 10,000 | ||

| 8 | Ship George Galley to Falmouth | 10,000 | ||

| 14 | Ship Molly to Glasgow | 12,000 | ||

| 21 | Snow St. Paul to Glasgow | 4,600 | ||

| 24 | Snow Hopewell to Liverpool | 6,835 | ||

| 31 | Ship Unity to Whitehaven | 7,150 | ||

| Nov 8 | Ship Harrington to London | 15,000 | ||

| 9 | Brig Success to Dumfries | 3,200 | ||

| 23 | Ship Hiscox to London | 6,000 | ||

| Dec 4 | Ship Bogle to Glasgow | 12,700 | ||

| 11 | Snow Tryall to Glasgow | 4,000 |

| Date | Ship and destination | staves | headings | hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan 15 | Ship Rebecca & May to London | 2,500 | ||

| 16 | Ship Allan to London | 3,000 | ||

| Febr 1 | Ship London to London | 6,000 | ||

| 17 | Sloop Hampstead to Barbados | 500 | ||

| 20 | Snow Elizabeth to Glasgow | 6,000 | ||

| Mar 20 | Billender Morpeth Packet to London | 3,000 | ||

| 21 | Ship Duke of Cumberland to Bristol | 5,000 |

| Date | Ship and destination | staves | headings | hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 21 | Ship May to Glasgow | 8,000 | ||

| 23 | Ship Eglington to Glasgow | 6,000 | ||

| June 16 | Ship Nancy to Bristol | 10,588 |

| Date | Ship and destination | staves | headings | hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 22 | Schooner Mayflower to Barbados | - | 300 | |

| 29 | Sloop Eliza to Barbados | 750 | ||

| Sept 4 | Schooner Peggy to Barbados | 3,000 | 1400 | |

| 13 | Sloop Bobby to Barbados | 5,000 | 2000 | |

| 16 | Schooner Mayflower to Barbados | 17,000 |

| Date | Ship and destination | staves | headings | hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May 2 | Sloop John & William of Va. to Barbados | 500 | ||

| 27 | Schooner Molly of Va. to London | 4,000 | ||

| June 14 | Ship Pretty Nancy to Bermuda | 5,800 | ||

| 17 | Ship Monmouth to Liverpool | 3,440 | ||

| Sept 23 | Ship Blanden to London | 4,500 | ||

| Oct 1 | Ship Duke to Bristol | 7,358 | ||

| 7 | Ship Buchanan to London | 9,000 | ||

| 8 | Ship Dragon to London | 7,000 | ||

| 19 | Brig Ranger to Bristol | 1,100 |

| Date | Ship and destination | staves | headings | hoops |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oct 5 | Snow Nottingham to Hull | 8,150 | ||

| 7 | Sloop Betsy to Barbados | 400 | 1840 | |

| 11 | Sloop Eliza to Barbados | 11,000 | 3000 | 500 |

| 22 | Brig Thistle to Ayre | 3,000 | ||

| 31 | Sloop Betty to Barbados | 8,209 | 5206 | |

| Nov 4 | Sloop Flying Post to Monserat | 4,200 | ||

| Dec 4 | Sloop Orphan Tehoa to Barbados | 26,000* | 3000 |

Exporting of staves, headings, and hoops.

Virginia Gazette, 30 September 1737:

Clear'd out: April 16 Ship Stanton for London 3435 Pipe hogsheads and Barrel staves. 21 Ship Cato for London 5000 hogshead staves. 26 Ship Dolphin for London 4600 Pipe Hogsheads, Barrel staves, and headings.

Upper district of James River between 25 October 1763 and 25 October 1764. 566,800 staves 9,250 hoops.

Between 25 October 1764 to 25 October 1765: 609,334 staves 3,950 hoops. Virginia Gazette, Purdie and Dixon, 12 February 1767.

Between 25 October 1765 to 25 October 1766: 560,459 no hoops listed.

Importing of Staves:

Upper District of James River: 25 March 1745 to 24 June 1745:April 18 Snow Mary & Betty from Maryland 3,000 barrel staves. June 18 Snow Molly, Lower District 4,100 staves. Virginia Gazette, 10 October 1745.

29 June 1745 to 29 Sept. 1745 July 23 Snow Happy from Newcastle 4,200 staves. Aug 14 Ship Unity from Newcastle 7,000 staves.

xiii.Virginia Gazette, 5 May 1738

Prices of staves in Philadelphia - 1738 By the thousand: stave, pipe 5 £ Hogshead 3 £ 5 s. Barrel 40 s.

Chamber's Encyclopedia, 1761.

English measure of capacity of liquids. Barrel - 31½ gallons, wine measure. 36 gallons, beer-measure. 32 gallons, ale-measure. Hogshead: 63 gallons, wine-measure. 54 gallons, beer-measure. 48 gallons, ale-measure. Pipe: 126 gallons, wine-measure. 108 gallons, beer-measure. (not listed — ale measure)

| Pipe | = 4 barrels or 2 hogsheads. |

| Hogshead | = 2 barrels, ½ pipe. |

Plate I

Plate I

Diderot.

- Worker a is preparing a stave over the block using a cooper's curved axe (page 1).

- b is shaving a stave on the shaving-horse (page 3).

- c is planning a stave over the jointer (page 4).

- d is mounting a barrel (page 6).

- e is tightening the barrel with a windlass that draws the staves tights (page 7).

- f making the notch on the hoop (page 16).

- g placing the cross-bar with a cant-hook (page 18).

- h driving the hoops with a driver or drift (page 17)

Plate II

Plate II

Déscriptions de Arts et Métiers.

- Fig. 1Worker who is preparing a stave with an axe over the block.

- Fig. 2Work who is shaving the stave over the block with the broad axe.

- Fig. 3Manner of cutting a stave over the shaving-horse: the worker is seated with a leg over each side of the bench, and with a draw-knife cuts the stave. The stave is held in the vice by pressing across-piece below with his foot.

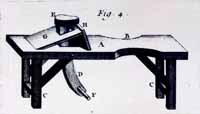

- Fig. 4Worker dressing the stave over the blade of the jointer.

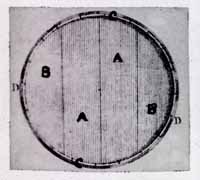

- Fig. 5Planks for the bottom placed on an old barrel. Worker traces a mark for cutting with a compass.

- Fig. 6Worker who saws the planks for the bottom, following the mark.

- Fig. 7Worker who mounts or builds a barrel, and who arranges the staves around the hoop.

- Fig. 8When the barrel is held at one of its ends with one or two hoops, each stave a the opposite end tends to move apart and in order to press them together the cooper uses the windlass and places a hoop similar to the other end hoop around them to hold them securely.

- Fig. 9The barrel placed in the cutting-horse. The worker forms the groove by moving the croze around the interior circumference of the barrel.

The Various Operations in Making a Barrel

Most of the operations described are from Déscriptions Des Arts Et Métiers Art Du Tonnelier, Tome VII, Neuchatel, 1777. Ed. J. E. Bertrand.

The section on tools, pages 30 to 42, are from Diderot, Recueil De Planches, Tonnelier, Tome X, Paris, 1777, unless otherwise stated.

The various operations described:

- 1. Preparation of the staves, pp. 1-5.

- 2. Mounting the barrel, pp. 6-8.

- 3.Trimming the staves and cutting the croze, pp. 9-12.

- 4.Preparation of the cross-pieces for the bottoms, pp. 13-15.

- 5.Mounting the bottoms, p. 15.

- 6.Method of placing and fastening the hoops around a barrel, pp. 16-17.

- 7.7. Re-enforcing the bottoms, pp. 18-19.

- 8.The bung hole and parts of a barrel, p. 20.

- 9.Iron re-binding hoop, p. 21.

- 10.Making hoops. (from Edlin) p. 22-25.

- 11.Illustration A. Rough preparation of material for staves and bottoms, p.26.

- 12.Illustration B, Break, p. 27.

- 13.Flagging iron and il1ustration of use, p. 28.

- 14Cooper's brace or dowelling stocks, p. 28.

- 15.Cleaver or splitter. Preparation of the cane for binding hoops, p.29.

- 16.Cooper's tools, pp. 30-42.

- 17.Evidence of cooper's tools in colonial Virginia, p. 43-44.

- 18.Evidence of iron bound casks, p. 44.

- 19.Bibliography, p. 45.

Footnotes

PREPARATION OF THE STAVES

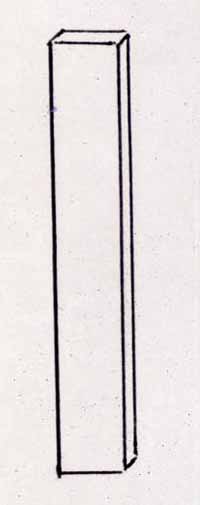

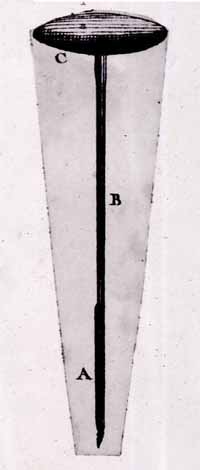

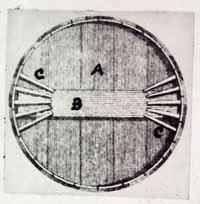

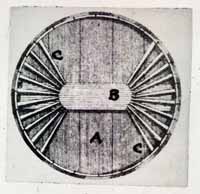

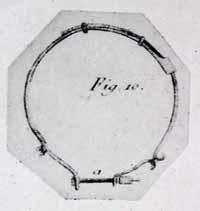

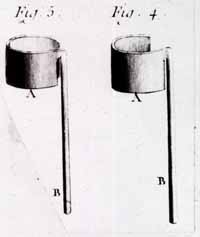

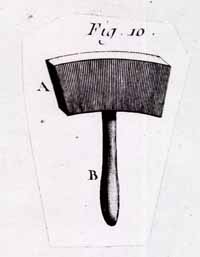

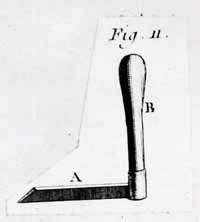

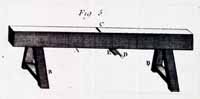

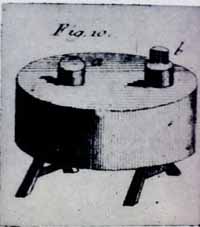

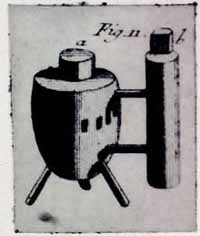

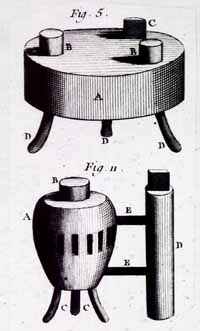

The cooper stacks his stave-wood or stuff (an eighteenth-century expression to designate the wood an object is to be made from) close to the block he is going to cut them on. He has two types of blocks for this purpose: 1. A round block of wood with legs raised about three feet from the ground. On the surface of the block are two up-right smaller pieces, one smooth at the top and the other with a short extension, Fig. 10.  Fig. 10 2. Another type of block is one made from a wooden hub of a wagon, in the opening where the axle of the cart was inserted is placed a smaller block and to the side of the hub is placed an upright piece that has on its top a small raised piece, Fig. 11.

Fig. 10 2. Another type of block is one made from a wooden hub of a wagon, in the opening where the axle of the cart was inserted is placed a smaller block and to the side of the hub is placed an upright piece that has on its top a small raised piece, Fig. 11.  Fig. 11 Note that the working surface of each of these blocks is similar Although these blocks greatly ease the cutting of the stave-wood or stuff they are not altogether necessary as this work could be performed on any hard surface. Note in plate I, Diderot, worker a is preparing a stave over the hub type block; and in plate II, Déscriptions, Figs. 1 and 2.

Fig. 11 Note that the working surface of each of these blocks is similar Although these blocks greatly ease the cutting of the stave-wood or stuff they are not altogether necessary as this work could be performed on any hard surface. Note in plate I, Diderot, worker a is preparing a stave over the hub type block; and in plate II, Déscriptions, Figs. 1 and 2.

To understand better the processes performed on the stave one should keep in mind the shape of a barrel. The fact that it bulges out in the middle and is of a circular shape. Therefore it is necessary that each stave is given the proper shape to accomplish this. These operations require experience and skill on the part of the worker.

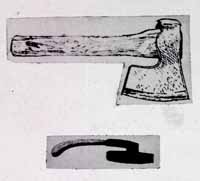

First preparation: on the block with a froe and broad or side axe.

The cooper takes the stave-wood or stuff and placing it on the block roughly cuts it with the frow into the proper size. Then with a broad or side axe he proceeds to roughly shape the stave as follows:

2.

Side or Broad Axe

Side or Broad Axe

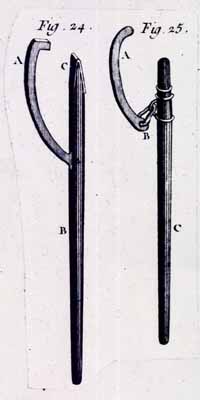

Froe, Frow, or Fromard

Froe, Frow, or Fromard

- (1)Cuts it into a rough shape and to size, fig. 1

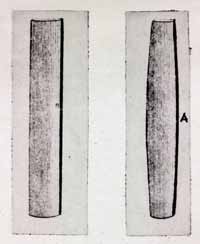

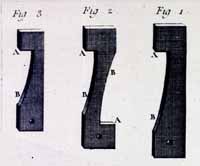

- (2)Trims the outside middle portion of the stave lengthwise sos that the middle is thicker than the sides. This gives a convex shape to the outside of the stave, fig. 2. (You will note in the illustration, figure 2, that only the exterior part of the stave is given a semi-circular shape. The Author in Déscriptions states that it is not necessary to shape the interior of the stave in a concave manner. However, the interior of most staves were given a concave shape.)

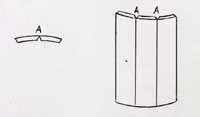

- (3)Cuts the width at each end so that the middle width is greater than the two ends, fig. 3. (see illustration A).

This latter operation, number 2, is necessary since the top and bottom of a barrel are smaller in diameter than the middle or bulge, as it is called. Therefore by cutting the width of the staves narrower at the two ends than in the middle, the hoops, when placed around the staves and tightened, draw in these narrow ends and gives the barrel a smaller diameter at the top and bottom than in the bulge.

3. Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Cut narrow at the ends, wider at the middle A.

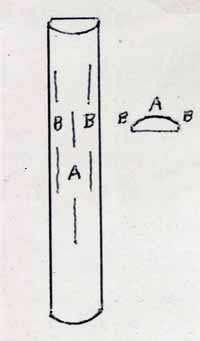

Second preparation: on the shaving-horse with a draw-knife.

The stave is then held in the shaving-horse between the jaws, H & E, and setting on the bench the cooper draws the draw-knife over the roughly cut surfaces he has previously made, further smoothing them out.

This operation is shown in Plate I, worker b; and in Plate II, fig. 3.

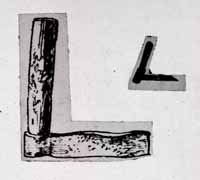

4.Third preparation: on the jointer. Bevel of the stave.

He then finishes the stave with the use of the jointer. On the jointer the bevel or slope to the edges of the stave are cut. The worker holds the stave uprights and sideways slightly inclining the stave as he pushes it over and away from himself on the blade of the jointer, and thus cuts the bevel or slope. The use of the jointer is seen in Plate I, worker c; and Plate II, fig. 4. See illustration below.

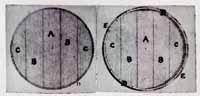

Staves beveled and placed together. A is the slope.

Staves beveled and placed together. A is the slope.

The purpose of this bevel is to give the circular shape to the barrel. When the staves are mounted the outer edges of the staves come together while the inner edges are separated. When the hoops are applied and drawn these inner edges will joine.

When these operations are completed the staves are then ready for mounting.

Some coopers have patterns for the purpose of the curve or convex shape of the stave for various types of barrels. These patterns are placed over the exterior surface of the stave to determine if the stave has the right curve.

Another similar pattern is used for marking and checking the bevel or slope of the stave. You will note that the part a b instead of being perpendicular as in the other

5.

patterns has a definite slope. This slope is used to measure the bevel of the stave. When the pattern is placed over the stave the space formed by a b is the slope desired.

5.

patterns has a definite slope. This slope is used to measure the bevel of the stave. When the pattern is placed over the stave the space formed by a b is the slope desired.

Mounting the barrel1

When the staves are prepared they are placed in a stack ready for mounting.

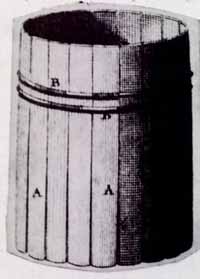

To mount the barrel he begins by tieing four hoops whose dimensions will conform to the barrel he is constructing. Two of these hoops, called bulge-hoops, will be placed approximately six inches from each side of the bung-hole and the other two hoops, called head-hoops, are placed near the cross-groove at both ends. The cooper, in order to be exact in making these four hoops, has several iron hoops of different sizes according to the gage of the barrel that he proposes to construct. It is around these iron hoops that he binds the hoops mentioned above. He arranges the number of staves he feels will form his barrel as shown in fig. 1, or places them upright along a wall.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Bundle of hoops

A - the bundle.

B - the stave prop.

C - the hoop.

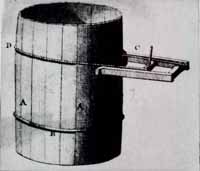

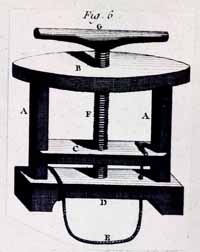

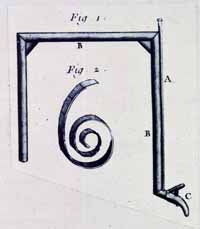

The cooper then takes one of the head-hoops that will regulate the dimension of the barrel at the cross-groove. On the inside of this hop he screws the cooper's vice, fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

b - the cooper's vice.

He first chooses the largest stave and leans it against the vice. At the side of this one he places a second, third, fourth, etc., fig. 3. When he has only a small place left to fill and his last stave will not fit he either trims one to fit, or removes the preceding stave and trys to fill the space with one wider.

Fig. 3. Setting up the Staves.

Fig. 3. Setting up the Staves.

When all the staves are in the hoop he strikes them at the top and on the inside to make them fit in place. He then places one of the bulge-hoops, which is larger than the head hoop, below the first head hoop and drives it in place around the staves, fig. 4.

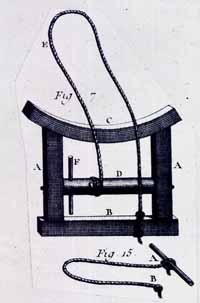

To finish the other end, he turns it over and places the rope of the windlass around this un-hooped end, fig. 5. The rope is tightened by means of the small lever b, which when turned draws in the staves. Around this end he then places the second head hoop, drives it down, and releases the windlass. He then places the second bulge hoop below the head hoop and drives it in place, fig. 6. The barrel, now held by four hoops, is ready for the operation of placing a head at botheach ends.

8. Windlass

Windlass

E - the rope that goes around the staves.

C - the part that is next to the staves.

TRIMMING THE STAVES AND CUTTING THE CROZE.

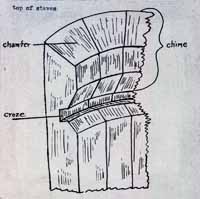

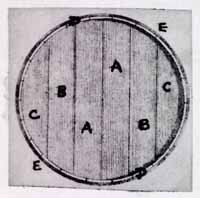

The barrel is now mounted but neither the outside nor inside of the barrel forms a perfect round appearance, rather the various staves form a polygon. This necessitates two operations on the inside top edges of the staves before one can cut the croze for receiving the bottom of the barrel. To better understand these operations study fig. 1. You will note that the croze is a recessed groove cut into the staves in which the bottom will fit; the chime is that portion between the croze and the end of the barrel; and the chamfer is the sloping ends of the staves.

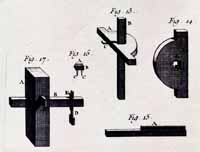

10.Study the tool called a croze in fig. 2. A, B, C, are from Diderot and Déscriptions and D is from a modern tool catalog. The similarity is obvious. In D note the iron of the croze — saw like teeth enclosed in a cover of sheet-iron. Déscriptions describes the iron of the croze in the same manner. This cover is adjustable as to depth of cut desired. In making the croze or groove in the staves the guard a runs around the edges of the stave and regulates evenly the cut of the saw tooth blade on the inside. The croze is generally cut 5 or 6 inches below the edgesends of the staves. ? PB

The two necessary operations before the croze can be cut are: first, the edges of the staves must be equal, if not this would give an uneven cut tot he croze. Second, the interior of the staves where the croze is to be cut must be smooth and circular. If not this would give an unequal depth to the cut.

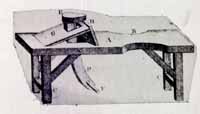

Trimming the staves: The barrel, held by the hoops, is placed up-right on an even surface and the staves struck in place and even with the ground. The barrel is then placed, with the even end toward the back, in a trimming-horse, fig. 3. He then, with a hatchet, cuts off the uneven staves.

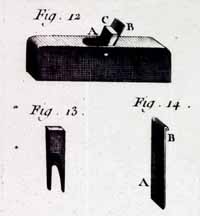

11.The edges are then smoothed with a "sun" or "topping" plane. Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. "Sun" or "Topping" plane.

Fig. 4. "Sun" or "Topping" plane.

Smoothing the interior of the staves: So that the croze will have an even depth the surface of the staves on the inside will have to be smoothed. This may be performed with a round shave, fig. 5. You will note in figure 1, a recessed area in which the croze is cut. This is cut with a howel, fig. 6. This has a convex sole and iron. This makes a smooth circle for the croze to follow.

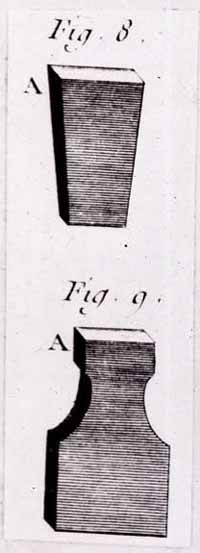

Chamfer: This operation is not necessary but is done on most barrels, See fig. 1. The author of Déscriptions states that this gives a certain neatness to the barrel "without doubt because our eyes are accustomed to it." He also states that it is easier to carry by its ends with this chamfer and further that it is claimed that the wood by being chamfered is less likely to splinter. The tool used is a chamfer or sometimes called a "jigger." Fig. 7.

12.Cutting the croze: The croze is cut while the barrel is fastened in the trimming-horse with the croze, fig. 2. The croze or groove is cut from 1/6 to 1/4 inch deep depending on the type of barrel made. Déscriptions states that this operation does not demand a great skill but only force and precise attention so that he will not give the groove more depth in one place than another.

The author of Déscriptions inserts an interesting sideline at this point. He writes that in some coopers' shops where each worker has a set task to perform the groove-cutter plays a trick on the apprentice by giving him a barrel with the edges badly trimmed so that when he runs the croze around the circumference of the edges the cut would be uneven!

The croze made the cooper can now arrange the bottoms that are to form the two ends of the barrel.

PREPARATION OF THE (CROSS-PIECES FOR THE HeadsBOTTOMS.)

The wood that is to be used to make the stretchers or cross-pieces for the bottomsheads would be prepared in the same manner as the staves. They would be first roughly cut into size on the block with a frow and further shaped with the adze or cooper's axe. They then would be placed in the shaving horse, and the outer side only would be smoothed down and the edges would be leveled by a plane or on the jointer so that when joined there would be no intervals between them.

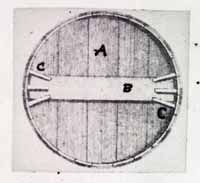

The bottomsheads of the barrel may be made from several pieces; four, five, or six. The plank or two planks that are to make the center of the bottomsHeads are generally larger than the side pieces. Déscription calls the center piece or pieces the main or principle piece; the side pieces, braces; and the corner pieces, cants.

| A or AA | - main or principal piece. |

| (Middle piece). | |

| B B | - the braces or side pieces. |

| C C | - The cants. |

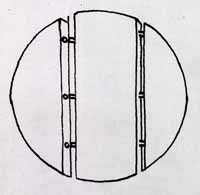

To cut the pieces into the desired diameter for the bottomsheads of the barrel under construction he first measures with a compass the diameter at the top of his mounted staves at the place he has cut the croze and then laying the planks for making the bottoms on an old barrel and clamping them down with a clamp he places the point of one arm of the compass in the center of the middle piece and proceeds to mark with the other arm of the compass around the planks thus marking where they are to be cut. Plate II, fig. 5, shows the worker marking the planks for cutting.

Bottom pieces marked to be cut. A - the mark.

Bottom pieces marked to be cut. A - the mark.

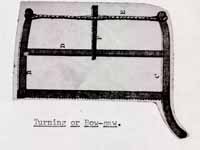

Each of these pieces are then placed on the bench of the shaving-horse and holding them with his knee, as shown in Plate II, fig. 6, he saws the planks with a turning or bow saw by following the trace marked by the compass but being sure to leave the trace mark visible.

He then forms a bevel or slope at the edge of each plank so that they will fit into the croze he has made in the staves.

Cooper's saw (Diderot)

15.

He places, in turn, each plank in the jaws of the shaving-horse. In this operation the mark that he left on the planks serve as a guide for this slope. He uses either a plane or the chamfering knife for this purpose. The planks when finished are then ready to be placed in the barrel to form the bottoms.

Cooper's saw (Diderot)

15.

He places, in turn, each plank in the jaws of the shaving-horse. In this operation the mark that he left on the planks serve as a guide for this slope. He uses either a plane or the chamfering knife for this purpose. The planks when finished are then ready to be placed in the barrel to form the bottoms.

MOUNTING THE BOTTOMSHeads?

To mount the bottomsheads tho cooper loosens the head-hoop or the barrel. First he places the two corner-pieces or cants in the croze of the staves and then the side pieces and strikes them with a mallet so as to enter the croze.

With these pieces in place there remains but one opening for the middle piece and hence the cooper can no longer place his hand in and under the cross-pieces as he places this last one in place. He uses the cooper's vise which he inserts into the middle-piece and using this as what one might call a handle, places the middle piece in the croze. The staves are then struck all around on the outside with a mallet to drive them more firmly in the croze and tight. Then the head-hoop is replaced and tightened.

METHOD OF PLACING AND FASTENING THE HOOPS AROUND A BARREL

The hoops are always longer than the circumference of the barrel at the place they are to be fastened. In order to bind the barrel the cooper takes a hoop and places it around the barrel at the place it is to go. He holds one end of the hoop in his right hand and with the left holds the same side of the hoop at about three quarters from the right hand. With the right hand he applies that end against the barrel at a place he has previously marked. Thus the middle of the hoop is raised and with his left hand he successively moves around the hoop pressing it against the barrel. When he reaches the middle part of the hoop he raises it against the barrel. When he reaches the middle part of the hoop he raises this right hand so that the starting end of the hoop he first applied against the barrel is now raised a little and places his right hand where his left now holds the hoop. He thus literally walks around the barrel pressing his hoop in place. When he reaches the end from where the excess portion if to be cut leaving enough space to place the notches he cuts at each end in order to bind the hoop together. He then removes the hoop, cuts it, and notches the ends. This may be seen in Plate I, worker f. He unites the two ends by placing the notches in one another and binds it at this place with blades of cane. He then places the hoop over the barrel.

17.So as not to damage the hoop when forcing it down and around the barrel at the place marked he uses a driver or drift, a sort of wedge of wood or iron which he strikes with a mallet forcing the hoop to descend. Thus the barrel is completed. This last operation may be seen in Plate I, worker h.

RE-ENFORCING THE BOTTOMSHeads

It is sometimes necessary to re-enforce the bottoms heads of large barrels. This is done by the use of a cross-bar run opposite to the cross-pieces that formed the bottom and is held by pegs that are driven into the ends of the staves.

Pegs. A - the head.

Pegs. A - the head.

B - the point.

The bar to support the bottoms? is composed of a piece of wood the diameter of the bottomhead. it is about four inches wide and one inch thick. This bar is prepared with an axe and smoothed with a plane. The ends are beveled to a point 5 or 6 inches from the ends. This bevel is the length and slope of the pegs that will hold it in place.

In the ends of the staves are bored holes with the bar-borer that serves for the pegs to be driven into. This hole is made about 2 inches above the bottom and is the diameter of the narrow end of the pegs. The pegs are tapered, cut at right angles at the taper end and are 4 or 5 inches long. He first drives these pegs in the holes on one side and then places ? under the pegs and on top of the bottom the cross-bar. This tends to raise the other end of the cross-bar and in order to press this end down the cooper uses a cant or lever hook.

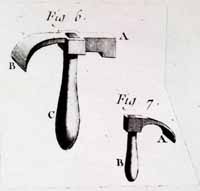

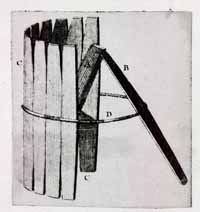

He places a of the hook against a hoop and the end b over the cross-bar and using the handle as a lever raises it forcing this end of the cross-bar down. Thus holding it he secures it with similar pegs as he did the other side. See plate I, worker g. Illustration following page.

19.| Fig. 1. | Cross-bar held at each end by three pegs. |

| Fig. 2. | Cross-bar held at each end by five pegs. |

| Fig. 3. | Cross-bar held at each end by ten pegs. |

| A - | the bottom. |

| B - | The cross-bar. |

| C - | the pegs. |

| A - | bung-hole. |

| D - | cross-bar. |

As both bottoms of a liquid barrel are securely fastened it is necessary to have an opening in the middle of the barrel to extract the liquid within. This is referred to as a bung-hole and the plug used for closing the bunghole is called a bung. The tool used to bore this opening is called a bung-borer, see illustration.

From: The Wooden Barrel Manual, Revised, 1951, The Associated Cooperage Industries of America, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.

From: The Wooden Barrel Manual, Revised, 1951, The Associated Cooperage Industries of America, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.

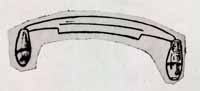

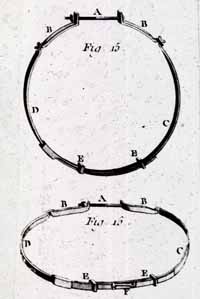

Iron re-binding hoop.

The iron hoop illustrated is for the purpose of re-binding-casks of wine and other liquids.

Various liquid casks were stored in caves or cellars where the dampness might tend to rot the hoops. The hoops are more likely to rot than the staves and therefore it is necessary that these casks be inspected from time to time and any hoop that need replacing is taken care of. If it was not advisable to replace the hoop with a wooden one an iron hoop was used. This is made of sections, flat but circular and the sections were hooked together. At the end is a screw-nut that is drawn together when the hoop is placed around the barrel. Déscriptions des Art et Métiers)

MAKING HOOPS.

The making of hoops was generally a separate craft, although it is more than probable that the colonial cooper in most cases made his own hoops and staves.

Hazel wood was the favorite material, though chestnut, oak, birch, and other types of wood are used. Ash is used for stronger hoops intended for special purposes.

Method of making: There are three stages in the making of a hoop:

1. Cleaving:

The cleaving of the rod is usually done with an adz, worked down the rod by hand, splitting it into two or more sections. During this process the rod is pushed against a wooden frame or break, consisting of two posts, one upright and the other nearly so, driven into the ground about nine inches apart at the base, and bound together at the top with a withe of twisted hazel. See illustration B.

2. Shaving:

The outer bark is left intact, but the inner core of wood has to be shaved off each hoop length to allow it to bend freely. The hoop is therefore fixed to a three-legged upright frame, or else to a horizontal wooden structure called a mare, and clamped firmly at one end while the hoop maker pulls his draw knife or shave over its inner surface until the right degree of thinness has been attained.

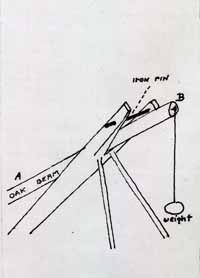

Description of a shaving-frame or break:

The shaving-frame or break consists of a tripod, of two slender legs and one stout one, fixed firmly in the ground. The stout one of oak, projects above the others and is cut out at the top to form a wide groove within which rests an oak beam free to picot over the top of the tripod. This beam is set slanting down towards the ground; the hoop length is laid on it and the hoop shaver leans over it to draw his knife towards him. At its upper end a weight is suspended 23. to act as a counterbalance, so that the beam can swing up and down like a see-saw. An iron pin fixed at the top of the tripod secures the hoop length in such a way that when the shaver presses his left knee against the beam the hoop length is nipped in a vice-like grip; when he eases up, the hoop length is immediately freed and can be shifted to a fresh position.

3. Shaping of the hoops.

If the rods are green they may be coiled without much effort, but if allowed to dry must be heated or steamed in order to restore their pliancy.

The rod may be forced between a revolving log and a wooden bar, or between a roller and a taut leather driving belt, or driven down between two parallel iron plates. Yet another process is to soak them well, bend them within a cylindrical iron tank, and then allow them to dry there. But in many cases the final curving that fixes their shape is done on a curious wooden frame supported on poles some three feet off the ground, with eight spokes radiating from its center. Each radial arm carries a number of pegs at the required distance from the center, and by adjusting these the diameter of the hoops may be varied. Beside this frame is set the strong truss or shive hoop, usually of ash, which serves as a mould for the lighter hazel smart hoops, which are placed within it while their ends are nailed to secure them in their circular shape. Then they are bound together in bundles of six, enough for one cask, and sent to the cask makers.

Another method:

Hoops soaked in a stream to make them pliable are bent on a bending horse, a sloping beam fixed very rigidly to a low post and bearing a pair of iron jaws; by working the cleft through these jaws and bending it as it came, it was brought to the state when it could be bent into a circle. This final coiling was done at once, the cleft being inserted immediately into a stout ash truss hoop of appropriate size, where its two ends were nailed together.

Bending hoops in the vice-like jaws of the bending horse.

Bending hoops in the vice-like jaws of the bending horse.

Cleaving, shaving and stacking.

Cleaving, shaving and stacking.

Source: Woodland Crafts in Britain, H. L. Edlin, London, 1949.

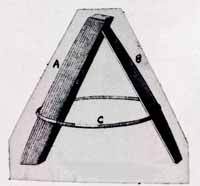

ILLUSTRATION A.

Fig,. 1.

Fig,. 1.

Edlin

Fig,. 2.

Fig,. 2.

Edlin

Fig. 1, shows the log being cut into rough sections for staves or bottoms. The axe is held by one worker while the other strikes the axehead with a bestle, splitting the log into sections.

Fig. 2. Shows the split section being roughly trimmed with an ax.

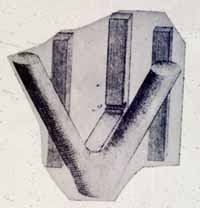

ILLUSTRATION B.

Edlin

Edlin

Break

This is a frame, a Y or V shaped wooden structure, sometimes forming a complete triangle, in an angle of which the material being worked upon may be stood or wedged in either a sloping or a level position. Workmen build their own breaks, and there are no standard sizes or patterns; one of the simplest forms is the natural fork of a tree supported on three short legs. (Edlin, p.14.)

Flagging iron

Edlin

Edlin

Caulking the joint between head and stave, with rushes.

A sort of prying-rod with a double-hooked head, used in flagging casks. It derives its name from the material used for caulking barrels, — Flag, a rush or cattail, which when dry, is used for caulking the joints of headings, and sometimes for caulking barrel joints. Illustration from Edlin shows method of use.

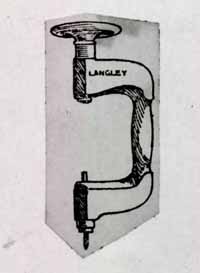

Cooper's brace or Dowelling stocks.

Used to make the holes in the headings for the dowels to fasten them together, see illustration.

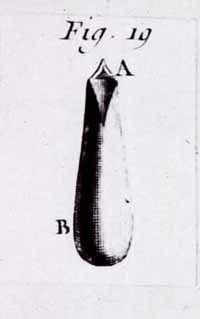

Fig. 19. Cleaver of splitter.

Edlin.

Edlin.

It is made from a piece of box-wood or any other hard wood. About 7 or 8 inches long. The head is parted in three grooves or spouts, of which each separation has a sharp edge. It is used to part the stalks of wicker in threes. To do this they first start the large end of the wicker in threes with a knife, then insert the cleaver and guide it down the wicker with a half-circular motion until they reach the end. The illustration from Edlin shows the method of use.

(Edlin, p. 14) For cleaving small material: "For smaller material, such as ending in a metal point with radiating ribs, which force the wooden rod to split into sections as the cleave is pushed down it. In most forms of cleaving it is the "feel" of the wood rather than the sight of it that guides the craftsman's hand, and one worker in hazel has told me that once a cleft has been started he can keep it running with his eyes shut."

[Cooper's Tools]

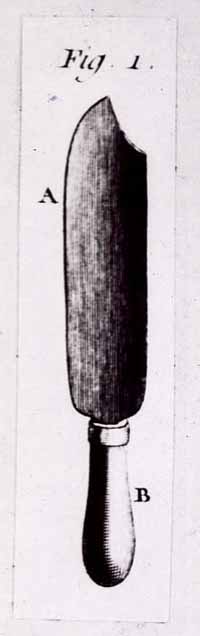

Fig. 1. Billhook. Sharp edge. Used to point wood.

Fig. 2. Cleaving-knife: Double beveled sharp edge. Used to trim rough wood. Or to rough-hew the work. Also could be sued to split the wood.

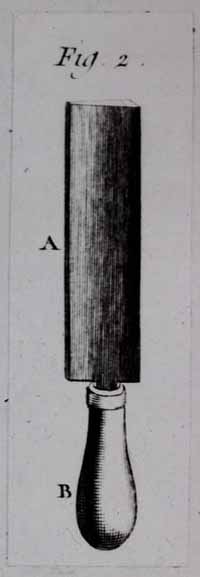

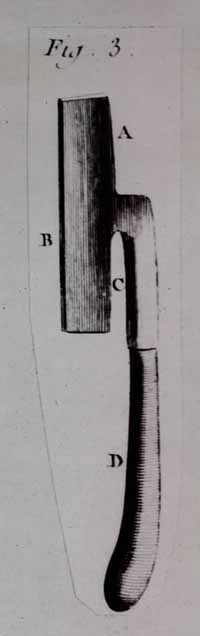

Fig. 3. Broad axe.

Used to roughly trim down the staves & to thin the ends of the hoops at the place where they are to be tied with wicket.

31.Figs. 4 & 5. Round shaves. Has a very sharp cutting iron, curved in a half circle and has attached a small handle to render it more easy to use.

Figs. 6 & 7. Adz. This tool is used to round off a piece of work on the inside.

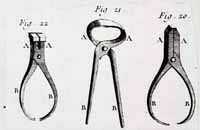

Fig. 20. Flat pincers.

Fig. 21. Tongs or pincers.

Fig. 22. Square pincers.

Fig. 10. Mallet.

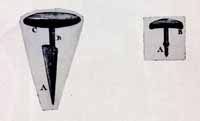

Fig. 11. Froe. A. cutting blade, B., handle. Used to split the stave stuff.

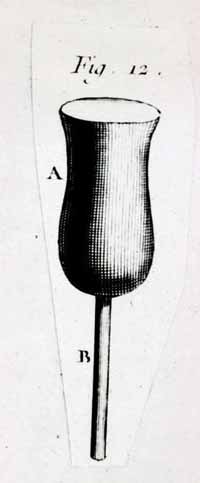

Fig. 12. Mallet or beetle, used to strike the frow.

The cooper places one end on the hoop that he wishes to drive and strikes the other end with a mallet in order to make the hoop tighten on the barrel.

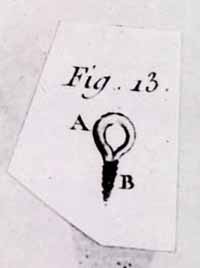

Fig. 13. Cooper's vise. See text.

Fig. 13. Cooper's vise. See text.

Fig. 134. Shows method of shaving the stave on the jointer.

Fig. 134. Shows method of shaving the stave on the jointer.

Edlin.

Figs. 1, 2 and 3. Patterns for measuring the curve of the staves.

Figs. 1, 2 and 3. Patterns for measuring the curve of the staves.

Cant hooks may be used to force the last or head hoop on the barrel.

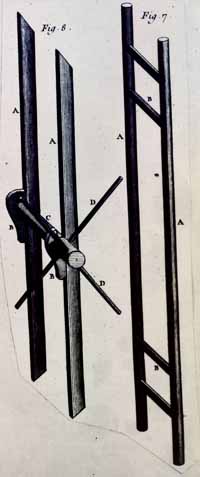

Figs. 13 and 17. Croze.

Fig. 16. Croze iron.

Fig. 14. Side piece of croze.

Fig. 15. Beam that fits into A of fig. 14.

Fig. 12. Cooper's plane.

Fig. 13. Wedge

Fig. 14. The iron.

Fig. 15. Draw knife.

Fig. 16. Draw-knife. Appears to be a hollowing knife or hollowing-shave.

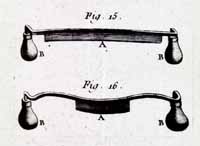

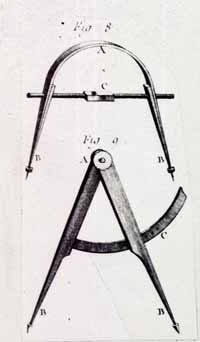

Fig. 8. Spring compass.

Fig. 9. Compass.

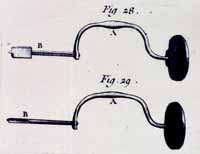

Figs. 28 & 29. Braces with their bits.

Figs. 28 & 29. Braces with their bits.

Fig. 31. Boring tool or small bung borer. Used on casks of wine.

Fig. 31. Boring tool or small bung borer. Used on casks of wine.

Handle is used instead of a hammer to drive in the spigot.

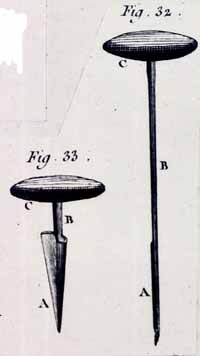

Fig. 32. Tap borer.

Fig. 32. Tap borer.

Fig. 33. Bung-borer.

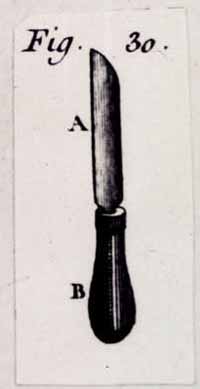

Fig. 30. étanchoir, a kind of knife to set stuffing. (étoupe) = Those that the cooper uses is ordinarily made from ragged linen cloth, reduced to lint. i.e. this would be used similar to the flagging iron.

Fig. 30. étanchoir, a kind of knife to set stuffing. (étoupe) = Those that the cooper uses is ordinarily made from ragged linen cloth, reduced to lint. i.e. this would be used similar to the flagging iron.

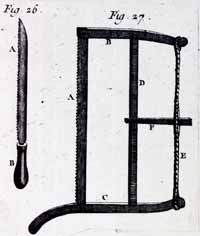

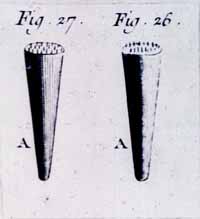

Figs. 26 & 27. Form used to make the bung (or plug).

Figs. 26 & 27. Form used to make the bung (or plug).

Fig. 26. Hand saw.

Fig. 27. Turning or bow saw.

Fig. 3. "La selle a rogner."

Fig. 3. "La selle a rogner."

Cutting or trimming horse.

Fig. 6 and 7. Windlass.

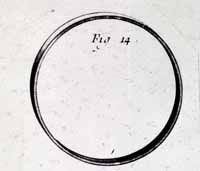

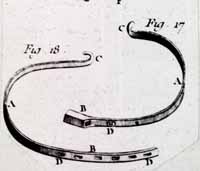

39.A re-binding hoop. Used when it is not advisable to replace a rotten hoop with a wood one.

Shows the various parts of the screw-hoop above. See page 21 for explanation of the use of this hoop.

40.Fig. 1. Bump, a kind of siphon made to transpose liquids.

Fig. 2. A chip of beech wood made to purify and clarify wine.

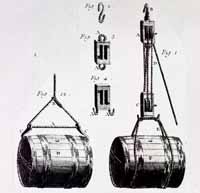

Fig. 7. Large sledge for raising or lowering barrels.

Fig. 8. Same type of sledge with a windlass.

41. Fig. 5 and 11. Blocks used to work the rough material into staves and bottoms.

Fig. 5 and 11. Blocks used to work the rough material into staves and bottoms.

Fig. 21. Drag, carriage for transporting barrels.

Fig. 21. Drag, carriage for transporting barrels.

Figs. 1 and 12. Slings and tackle for hoisting.

Figs. 1 and 12. Slings and tackle for hoisting.

Fig. 2. the hooks.

Figs. 3 & 4. The tackle block.

Evidence of cooper's tools in Colonial Virginia.

The below listed tools are by no means complete. It does indicate the kind of tools used in Colonial Virginia.

| 1671-72: | Gimlets, Hand saws, adzs, round shaves, fores, large compasses, Augers, Bills, cross cut saws.1 |

| 1678: | Large files, axes, augers, plaining irons.2 |

| 1701: | "To 2 old Cooper Joynters…1 Cooper ax" hand saws, drawing knife.3 |

| 1709: | large gimlets, smaller gimlets, Bung Augers, Augers, plain irons & spoke shave, Crouse (croze) irons, handsaws, Brod (broad) axes, Coopers Brod (Broad) ax, adzes, 1 Cooper's adz.4 |

| 1728: | Inventory of Thomas Lord Fairfax's estate: Listed under tools. 6 hand Saws, 4 adzes, 1 hatchet, 26 augurs, 6 Drawing Knives, 7 Spike Gimlets, 4 Crescent Saws, 2 Hhd. crows, 1 Hhd. Compass, 1 hoop Dog, 2 spoke Shavers, 1 hoop anvil, 2 cooper joiners, 4 dowell Bits, 4 whip Saws, 2 cooper adzes, 2 cooper axes, 1 coopers Vice, 1 hollow drawing knife, 1 heading * do (drawing knife), 1 large bung borer, 49 axes, 2 Crow bars, 1 Jointer Iron, 3 plane Irons, 2 Bung Borers. (Only those tools that could be used by a cooper were copied).5 |

| 1766: | Cooper's tools advertised for sale in Norfolk Virginia. Cooper's adzes, cooper's axes, jointer and coopers irons, carpenters and cooper's bits, cooper's vices and tools, compasses, augers, gimlets, drawing knives.6 |

| 44. | |

| 1771: | An order for Cooper's tools: 3 Drawing knives; 3 Howells, 6 dowelling Bitts, 3 adzes, 3 Axes; 3 Jointers Irons. This order was received by a Williamsburg Carpenter.7 |

Footnotes

- Edlin, H.L., Woodland Crafts in Britain, London, 1949.

- Bertrand, J. E. Déscriptions des Arts et Métiers, Tome VII, Art du Tonnelier.

- Chamber, E. Cyclopedia, London, 1768, volume III.

- Diderot, Denis, Recueil de Planches sur les Sciences, Les Arts Liberaux, et Les Arts Mechanique, Tome X, Tonnelier.

- Force's Historical Tracts, Virginia Richly Valued, volume III.

- Force's Historical Tracts, New Description of Virginia, volume II.

- Hazen, Edward - Popular Technology; or, Professions and Trades, New York, 1841.

- Hennel, Thomas, written and illustrated by - The Countryman at Work. London, The Architectural Press, 1949.

- Hening, William Waller, The Statutes at Large, Richmond, 1820, volumes, I, II, V, VI, VIII, and IX.

- Jenkins, J. Geraint, Country Life, March 28, 1957, - The Ancient Craft of the Cooper.

- The Oxford English Dictionary

- Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, Richmond, Virginia, volumes, XXXI and VIII.

- Wolcott, Stephen C. A Cooper's Shop of 1800. The Chronicle of Early American Industries, volume 1, number 9, January 1935.

- York County Records, Wills and Inventories, Book 22.

- The Wooden Barrel Manual , Revised, 1951, The Associated Cooperage Industries of America, Inc., St. Louis, Mo.