Brush-Everard House Kitchen and Surrounding Area: Block 29, Area E, Colonial Lots 164 and 165

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 203

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

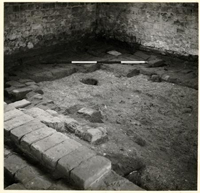

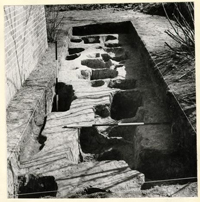

Frontispiece: An interior view of the Brush-Everard Kitchen, with its Period III extension, prior to excavation. The east - west brick work in the foreground served as the foundation for the Kitchen's Periods I and II frame north wall and remained as a partition after the north addition was erected. Photo from south - southeast. 67-SMT-358

Brush-Everard House Kitchen

and Surrounding Area

Block 29, Area EColonial Lots 164 and 165

REPORT ON 1967 ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS

CONTENTS

| Table of Figures | |

| Table of Photographs | |

| Acknowledgements | |

| Introduction | 1 |

| Precis of Brush-Everard House History | 2 |

| The archaeology of the Brush-Everard Kitchen and its surrounding area | 17 |

| Brief history of Lots 163, 164, and 169 from 1716 to 1770 | 31 |

| The archaeology of the northwest section of Lot 164 | 35 |

| Architectural evidence found during the present excavation | 40 |

| Conclusions | 43 |

| Footnotes | 45 |

| Appendix I, Texts of relevant records | 48 |

| Appendix II, Table of brick sizes and descriptions | 59 |

| Appendix III, Summary of excavation register numbers | 60 |

N.B. An illustrated summary of the artifacts has yet to be written and illustrated.

| Figure 1 | Section of stratigraphy across kitchen's north addition. | Following page 15 |

| Figure 2 | Section of stratigraphy across south end of first and second period structures. | Following page 16 |

| Figure 3 | Features predating first period. | Following page 18 |

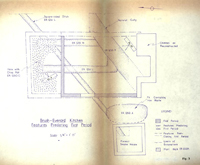

| Figure 4 | Second and third periods kitchen. | Following page 19 |

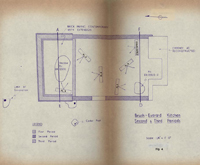

| Figure 5 | Colonial and late fence lines. | Following page 25 |

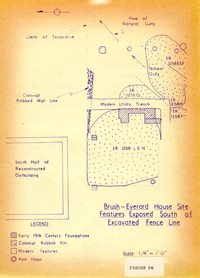

| Figure 6 | Features exposed south of excavated fence line. | Following page 30 |

| Figure 7 | Detail from Frenchman's Map showing relevant lots, with numbers added. | Following page 44 |

| Figure 8 | Archaeological site plan. | Attached to back cover |

| Frontispiece. | Interior of Brush-Everard Kitchen prior to excavation. |

| Plate 2. | Interior of kitchen's north extension, showing upper brick floor and lower paving. |

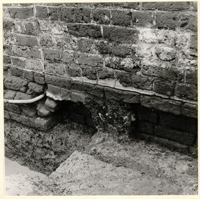

| Plate 3. | View of extension with pit cutting through early floor and marl, and brick foundation for north wall of Periods I and II. |

| Plate 4. | Southwest corner of kitchen with surviving portion of upper brick floor. |

| Plate 5. | Pit which was sealed by kitchen's lower brick paving. |

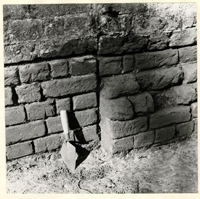

| Plate 6. | West wall juncture of north extension and main building. |

| Plate 7. | Exterior joint between kitchen's Period II east wall and north addition's east foundation. |

| Plate 8. | Destruction debris found beneath marl path of kitchen's north addition. |

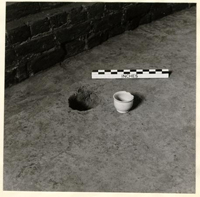

| Plate 9. | Small circular hole with intact drug pot found at bottom. |

| Plate 10. | One of two north/south shallow slots and deep northeast/southwest trench, which predate all stages of the extant kitchen. |

| Plate 11. | Post holes exposed south of kitchen's reconstructed chimney. |

| Plate 12. | Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century post holes southwest of existing smokehouse. |

| Plate 13. | Nineteenth-century chimney foundation southeast of existing "office". |

| Plate 14. | Some artifacts in situ in rubbish pit, E.R. 1268L and N. |

Plates 2 - 14 appear at the rear of the volume.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The Department of Archaeology would like to thank the personnel in the Research and Architecture Departments for their assistance on the Brush-Everard Kitchen excavation. In addition, we are most grateful to Mr. Douglas White for his surveying work. Mr. Daniel Barber was responsible for the photography and plan preparation.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL EXCAVATIONS ON THE BRUSH-EVERARD SITE

Introduction

Archaeological activity began in February 1967 as a re-excavation of the Brush-Everard House kitchen area, since sections immediately surrounding the extant building had been cross-trenched by Mr. J.M. Knight during the latter part of 1946 and the early part of 1947.1 The selection of this area, designated Colonial Lot 165, was influenced by Colonial Williamsburg's desire to obtain dating evidence for the extant structure, to gather information to substantiate existing records, and to continue the search for knowledge about the buildings and property for periods that are not as yet documented. This additional material was needed to enable the Department of Architecture to complete restoration of the kitchen's interior.

The reports of prior architectural and archaeological studies indicate that the existing outbuilding had evolved in at least three stages: (1) a frame structure resting on a 9" brick foundation; (2) the east and west weatherboarded walls replaced with others of brick; (3) the construction of a brick extension to the north making it necessary to also remove the original frame north wall.2

2The ground immediately surrounding the kitchen was found to be greatly disturbed by the laying of modern utilities as well as by earlier archaeological investigations. Therefore, most of the important information pertinent to the site's history was found inside the building. There is one exception, this being the discovery of numerous fence lines, both eighteenth and nineteenth century, running east/west, 1'0" south of the existing reconstructed chimney (south portion of kitchen). It was deemed necessary to dig areas south of the above-mentioned fence lines (north part of Colonial Lot 164) in an attempt to answer questions posed by unexpected features and stratigraphy found beneath and predating the kitchen structure.

In the interest of brevity, the texts of relevant records are grouped together in Appendix I. The archaeological report deals first with the extant kitchen and then with fence line evidence and finally with archaeological findings extending onto Lot 164.

Precis of the Brush-Everard House History

The first known owner of Lots 165 and 166 was John Brush, a gunsmith by trade, who acquired the land in 1717 from the trustees of Williamsburg.3 The deed, 3 which was entered in the York County records on July 8, 1717, states: "...in consideration of Thirty Shillings of Good & lawfull money of England to them [the Trustees] in hand paid ... Have Granted bargained Sold Remised Released & Confirmed ... unto the sd John Brush Two certain Lotts of Ground in the City of Williamsburgh designed in the Platt of the sd City of these figures 165 . 166."4

The above-mentioned title contained the usual stipulation that Brush or his heirs would have to erect a building or buildings on both lots within twenty four months or the property would revert to the trustees.5

It is evident that prior to 1717 there were no buildings on lots 165 and 166. Brush met all legal requirements since the property remained in his possession until his death in 1726. Therefore, by 1719, there were at least two major buildings on the land in question.

John Brush left a will dated November 26, 1726, in which he specified that his houses and lots in Williamsburg were to be divided equally between his unmarried daughter, Elizabeth Brush, and his son-in-law, Thomas Barbar, husband of Suzanna Brush. The will mentioned also that if the Legatees agreed that one should own all the property, the 4 other would receive one half the total valuation from the Possessor.6

Elizabeth Brush elected to sell her share of the buildings and property to her brother-in-law, Thomas Barbar. The deed substantiating this fact was entered in the records of the York County court on May 15, 1727.7 Barbar and his wife probably moved into the house soon after the above-mentioned transaction was completed; however, their occupancy was short-lived as Barbar died in 1727.

Thomas Barbar dictated, in his will dated May 10, 1727, that after his death, his Williamsburg property was to be sold and the proceeds be applied to "payment of his debts, his funeral expences, and to his Personal Estate."8 In accordance with Barbar's wishes, his wife sold the property to Mrs. Elizabeth Russell as recorded in a deed dated November 14, 1728.9

Elizabeth Russell has not as yet been identified. An entry in an account book of Edmund Bagge (1726-1733) leads to the conjecture that she may have been the widow of Andrew Russell.10

It is also possible that Elizabeth Russell and Mrs. Barbar were sisters since Mrs. Barbar was allowed 5 such easy terms (seven years to clear the title.) If they were in fact sisters, then from February 2, 1727, (when Elizabeth Brush, spinster, sold the property to Thomas Barbar) to November 28, 1728, (when Mrs. Elizabeth Russell, widow, acquired the property) she had married and become a widow. The above deed does not mention that Mrs. Russell and Mrs. Barbar were sisters but it does note that Mrs. Barbar was the daughter of John Brush. A thorough investigation by the Research Department into the York County records produced no additional information concerning Mrs. Elizabeth Russell.

In 1742 Lots 165 and 166 passed from Henry Cary II and his wife Elizabeth to William Dering, dancemaster. It is assumed that Elizabeth, wife of Henry Cary, was the former Elizabeth Russell. Unfortunately, the conveyance to Dering was recorded in the General Court records which were destroyed by fire during the Civil War.

William Dering had a rather dubious career as dancemaster and artist. He taught in some of the finer homes of the day, was a slave owner — having at least four in 1745, owned also in 1745 "one chariot with horses & harness, a shaise with two horses & harness, a body & a chair lined with blue cloth & a riding horse, saddle, 6 bridle & housing."11 Although he lived like a man of substance, he was continually in debt. An action of debt was brought against him in 1739 by William Prentis, George Gilmer, Henry Wetherburn, and John Harmer in the York County court. He was forced to mortgage his Williamsburg property in May, 1744, so that William Prentis, a Williamsburg merchant, could be paid £400. Dering evidently paid the mortgages in 1744 but the property was mortgaged again in 1745 to Philip Lightfoot of Yorktown. Dering appears to have been in continuous financial difficulty from 1744 to 1751 since there were numerous suits against him during that eight year period. In 1750, Dering gave an additional mortgage upon slaves and all his personal property to Philip Lightfoot. He also owed William Lightfoot £35 at this time and this fact prompted Dering to name William Lightfoot as his executor with the right to sell or mortgage the lots, houses, and goods if he (Dering) had not made payment on the last day of April, 1750. The last time Dering's name was mentioned in York County records was on January 21, 1751, in the suit - William Nelson vs. William Dering in which it is recorded that the "Sherif left a copy of the Petition Sumon and Account at the House of the Defendant."12

7Documentary evidence seems to indicate that Dering had moved to Charleston, South Carolina in 1749. Two notices in The South Carolina Gazette help substantiate this fact:

| December 11, 1749: | "William Dering. Dancing, 'the true French (and most approved) Method.' ". |

| November 12, 1750: | "This is to give Notice, to the Gentlemen and Ladies who have favour'd us with their Children, that on Tuesday the 18th of December next, at Mr. Gordon's great Room (commonly called Court-Room) there will be A BALL, to begin at six o'Clock in the Evening, by ... Dering & Scanlan."13 |

Lots 165 and 166 were sold at public auction in 1751 apparently after Dering had left Williamsburg. John Blair wrote in his Diary on February 14, 1751, that he had attended "Mrs. Dering's outcry"14 that day. It is unfortunate that Mr. Blair failed to state who had purchased the property, for definite ownership cannot be documentarily confirmed until 1779.

Henry Tazewell purchased Lots 163, 164, and 169 from John Tazewell and his wife in 1779 and the deed names Thomas Everard as owner of the property to the north (Lots 165 and 166): 8

[September 1, 1779]

[John Tazewell and wife

"...three lots denoted... 163, 164 and 169 and bounded by Palace Street on the West by the Lott of Thomas Everard on the North by the Lotts of John Blair, Esq. on the East and by the Market square on the South — and all houses..."15

to

Henry Tazewell

Consideration: 1200 pounds]

Thus, Thomas Everard definitely owned the property in 1779 but this leaves a documented ownership gap of 29 years (1751-1779). The title transfer in 1751 and all subsequent transactions, if any, probably were entered in the General Court records which unfortunately were destroyed by fire. A deed recorded in 1773, in which Everard acquired an adjacent lot (172), bears mentioning in that it helps form, at best, a conjecture concerning the ownership of Lots 165 and 166 in that year:

[September 10, 1773]

[John Blair, Williamsburg,

"... In consideration of three Lotts of Land in the said City conveyed by the said Thomas Everard to the said John Blair by Deed bearing date with these presents and also for and in consideration of the sum of five shillings by the said Thomas Everard to the said John Blair in hand paid... He the said John Blair hath bargained sold and confirmed unto the said Thomas Everard one Lott 9 of Land ... denoted in the plan of the said City by the figures 172 and was devised to the said John Blair by his Brother Doc. James Blair decd and all the Appurtenances thereon... forever.

to

Thomas Everard

Consideration: 15 shillings]

John Blair"16 [Recorded December 20, 1773]

It appears possible that Everard owned Lots 165 and 166 by 1773 and he purchased Lot 172 so that he might expand his gardens. Another bit of evidence was found in a letter from Everard to John Norton, London, dated August, 1770, in which he mentions that "Your Son has been sometime confined Sick at my Neighbor Mr. Wythes but is now pretty well recovered and gone to York."17 George Wythe would have been Everard's neighbor if he (Everard) lived on Lots 165 and 166; however, Lots 175, 176 and 177 on Scotland Street were also owned by Thomas Everard in 1770 and if he was living on these lots he would have been Wythe's neighbor likewise. It is also possible that Everard purchased Lots 165 and 166 in 1756 and moved to that property when he sold his Nicholson Street lots to Anthony Hay. Everard could have purchased the land in question in 1751 at the public auction, leased the property for 5 years, and then made Lots 165 and 166 his residence in 1756. It must be remembered that the above is more speculation than fact in that no definite 10 documentation was found to confirm these suppositions. However, in the course of excavations within the extant kitchen, a delftware plate fragment, identical to others unearthed on Everard's Nicholson Street property (Lots 263 and 264), was found, suggesting the presence of Everard on Lots 165 and 166 as early as 1756. This theory will be discussed in great length on page 23.

As these tentative conclusions would place Mr. Everard at the building now known as the Brush-Everard House for a quarter century, it is fitting to include in this report particulars about the man's life, positions held, and also the type of living to which he was accustomed, so that a mental picture of Thomas Everard, landowner and gentleman, may be formed.

Everard was obviously a man of some means. As early as 1745 he acquired Lots 263 and 264 from John Wall and sold them to Anthony Hay in 1756. In 1770, as previously noted, (page 9) he obtained Lots 175, 176, and 177, on Scotland Street, from Peyton Randolph. John Blair received the deed to this property (175, 176, 177) in 1773 in exchange for Lot 172. Everard also owned a plantation on Archer's Hope Creek near Williamsburg. In addition to being a substantial property owner, he also held a number 11 of important positions in the local government.

In 1743, Everard was clerk of Elizabeth City County, Virginia, and in 1745 was appointed deputy clerk of York County. He aspired to the position of full clerk in the November court of that year (1745) and he held this office until his death in 1781. Everard also served as Clerk of the General Court in 1766. In 1774, and again in 1775, he was a member of the Williamsburg Committee to elect a representative to the Continental Congress. Everard was offered the post of Auditor of Public Accounts in 1781, but this office was declined. He died sometime after October, in the same year (the last date on which his signature appears as Clerk of York County),18 and prior to February 19, 1782, when John Nelson was named Clerk in the room of Everard, deceased.

Much information about a man may be obtained from his shopping lists. Existing records show that Everard ordered goods from John Norton & Sons, London merchants, on February 10, 1773, and again on October 3, 1773. Items of interest from these purchases include: "fine materials & clothing for ladies and gentlemen, wearing apparel for slaves, materials to be used for home repairs — i.e. 100 lb. White lead ground in Oyl & 100 feet window Glass — 11 inches by 9½, and miscellaneous household goods such 12 as books, drugs, pans, brushes, etc."19 It is evident that Everard was not only interested in keeping himself and his family dressed in the taste of the time, but also his house servants. Furthermore, he appears to be the type of man who was interested in keeping his house and outbuildings in good repair. It is not unlikely that Everard made many improvements to the buildings and property during his twenty-five years of ownership.

Everard married Diana Robinson, daughter of Anthony Robinson of York County, but it is believed that she died prior to his death in 1781. They had two daughters: Frances, who had married the Reverend James Horrocks (Horrocks died July 23, 1772, and his wife in 1773) and Martha, who had married Dr. Isaac Hall of Petersburg. The Horrocks were childless but the Halls had two: Everard Hall and Diana Hall (both under age in 1781).

York County records do not contain a will or inventory of Everard's estate. Williamsburg Land Tax records which began in 1782 do not mention Everard as a property owner in the city; however, "Thomas Everard's Estate" is charged with "3 lots valued for tax purposes at £4.10 in 1783."20 In 1782, John Stith's name was entered in these 13 records as possessing "3 lots valued at £4.10", (Appendix I, part 6). It is presumed by the Research Department that Stith was living on the property in 1782 and was mistakenly recorded as the owner of the land. The error was then corrected in 1783 as shown above. This conjecture was based on the fact that many similar errors were made the first year these tax records began (1782) and subsequently corrected the following year. At any rate, John Stith again was entered as possessing the property in 1784 (presumably purchasing it from the "Everard Estate") and in 1787, a notation was made that Stith conveyed it to Dr. Hall. The next tax record concerning this land was recorded in 1788 when it was noted that "Dr. _____ Hall [conveyed] to James Carter 3 lots valued at £9.0.0." (Appendix I, part 6.)

Dr. Hall leased the Williamsburg property after Everard's death and at one time it was occupied by Mrs. Susanna Riddle, widow of Dr. George Riddle of Yorktown. The following letter from Isaac Hall addressed to St. George Tucker substantiates this fact:

14Apr: 19th [no year]

"... Present our best Respects to Col: Innis & request of Him to inform me how long Mrs Riddell occup [torn] our Houses in Williamsbg & as nearly as he can remember the Date of her taking Possession & quitting them—We would be glad likewise to know the opinion of the value of the Rent of them at that Time—"21

Mrs. Riddle moved to Williamsburg soon after her husband's death in 1779 with her two wards, Camilla and Rachel Warrington. She was a wealthy person in that she and her husband owned property in Scotland, the West Indies, and Yorktown. Williamsburg Land Tax records indicate also that she owned one lot in that city. Personal Property taxes in 1782 reveal that she paid on 15 slaves, 2 horses, 1 cattle and 4 wheels. It seems unlikely that a woman accustomed to fine living could bear to live on a one-lot section. One presumes, therefore, that Mrs. Riddle occupied Lots 165 and 166 and that while there she effected many improvements to the property.

In 1783, Mrs. Riddle paid Humphrey Harwood, (Appendix I, part 7.) carpenter and brick mason, £25.16.10 for materials and labor to repair, among other things, five outbuildings.22 The number of outbuildings seems to agree with the Frenchman's Map of Williamsburg (1782?) which shows five outbuildings northeast of the main house on Lots 165 and 166. Likewise the rooms, passages and stairs appear to correspond with those known to be on Isaac Hall's property. Harwood's accounts with Mrs. Riddle from February 1783 to October 1785 do not indicate that an addition to the kitchen was part of his repair work; however, artifacts from the 15 excavation of the extant extension give us a construction date of no earlier than the mid-eighteenth century and possibly as late as c. 1780-90. This is not to say that Mrs. Riddle was responsible for the construction of the kitchen addition but is mentioned only as a possibility.

Mrs. Riddle died in 1785 but apparently she was then living on her own property. This information was found in her executor's advertisement in 1785 and 1786. According to Williamsburg Land Tax records, Hall conveyed "3 lots valued at £9" to Dr. James Carter in 1788. (Appendix I, part 6). It is interesting to note that between 1783 and 1788 the valuation of the property for tax purposes had more than doubled (£4.10 - £9.0). This increase in value does not necessarily mean that improvements were made to the property since during these years an increase in tax evaluation was felt throughout the city.

James Carter, apothecary, was a son of John Carter, keeper of the Public Gaol. His brother William was also an apothecary in Williamsburg. Carter died in 1794; however, his "Estate" held the deed to Lots 165 and 166 until 1819. (Appendix I, part 6).

Milner Peters, son-in-law of Dr. James Carter, acquired the property in 1820 and occupied it for ten years.

Figure 1. Brush-Everard Kitchen

Figure 1. Brush-Everard Kitchen

Section of Stratigraphy across North Addition - oversized image

16

In 1830, Dabney Browne, a professor of humanities at the College of William & Mary, purchased the property "via Wm. T. Pierce who purchased of Elizabeth Peters widow of Milner Peters decd." Evidently Pierce was trustee in the transaction. Browne retained possession until 1847 when it was noted in the Williamsburg Land Tax records, "Formerly chd to D. Browne & Transfd to Daniel Custis in 1847." (Appendix I, part 6.)Curtis [sic] See: Research Report (1956), p. 32.

In 1849, Sydney Smith purchased Lots 165 and 166 from Daniel P. Custis [sic] and wife, Elizabeth. Smith and his ancestors owned the land until 1928 at which time it was purchased by Dr. W.A.R. Goodwin, trustee representing the Williamsburg Restoration.

The history of Lots 165, 166, and 172 is well documented throughout much of their life; however, the gaps in the documentation, unfortunately, occur in the period from which most of the excavated material dates (1745 to 1780). There is undoubtedly still a great deal to be learned from the soil surrounding the "Brush-Everard House" and its outbuildings, as shown by the huge quantity of artifacts found in this year's limited digging in areas that had previously been cross-trenched. It may be that further excavations will eventually resolve questions that are, as yet, unanswerable.

Figure 2. Brush-Everard Kitchen

Figure 2. Brush-Everard Kitchen

Section of Stratigraphy across South End of First and Second Period Structures - oversized image

The Archaeology of the Brush-Everard Kitchen

and its Surrounding Area

The excavation inside the existing kitchen commenced with the examination of the northerly addition and entailed the removal of its two successive brick floors. (Fig. 1 and Plate 2.) A shallow rubbish deposit (E.R. 1255E) was found beneath the upper pavement (Plate 3) and contained, among other items, an iron cooking pot fragment, two horseshoes (one being whole, the other a small fragment), along with ceramics dating up to circa 1825. Dirt and ash strata between the floors yielded artifacts with similar dates. Directly beneath the lower brick floor (the extension's first), a marl path was found extending east and west and cut through on either end by the builder's trenches for the addition's north/south walls. The east wall builder's trench was filled with brickbats and mortar, the latter overlying a small section of the above-mentioned marl walkway. This mortar was sealed by the lower brick floor. Finds from the marl layer (E.R. 1255R) were scant but among them was a pearl ware sherd which could not date prior to 1790. If this was not an intrusive fragment from the afore-mentioned rubbish pit (E.R. 1255E), it would mean that the north addition (whose builder's trenches cut 18 through the marl) was constructed after that date. Datable material from the east and west builder's trenches was scarce but the objects found dated no later than the mid-eighteenth century. But these trenches cut through earlier strata and were then backfilled with the same material, thus this evidence can only give a terminus post quem for the erection of the annex. The builder's trench for the north wall, unfortunately, contained no datable material.

On the basis of the foregoing scant evidence it may be concluded that the kitchen's north addition dates no earlier than the mid-eighteenth century, but possibly as late as circa 1790. However, it is clearly established that the extension's first brick floor and its walls were constructed at the same time.

Now that the floors in the third period area have been discussed, attention must be given to those within the main building (first and second period structures). A small portion of what appeared to be an upper brick floor was found in the southwest corner overlying a thick marl and oyster shell layer (Plate 4). The ceramics from this stratum (E.R. 1256A) dated to the last half of the nineteenth century; hence, the upper brick floor was placed there at a comparatively recent date.

Figure 3. Brush - Everard Kitchen

Figure 3. Brush - Everard Kitchen

Features Predating First Period

Directly beneath the above-mentioned marl layer and overlying the lower brick paving was a thin stratum of ashes. It was presumed that these represented the waste from the kitchen's hearth. The removal of the lower brick floor exposed a rectangular pit (E.R. 1256E-J), west of the reconstructed fireplace, containing five distinct layers, two of which were filled with ashes (Fig. 2 and Plate 5). The ceramics found on the bottom of the hole dated in the period circa 1790 to 1800. Still another stratum of ashes (E.R. 1256K), sealed by a layer of mortar flecks and also by the main building's first brick floor, yielded material dating as late as 1815-25. This evidence was found mostly in the northeast section of the room; therefore, the dates 1815-1825 represent the terminus post quem for the laying of the lower brick paving in that part of the building. Additional evidence, reinforcing the above-mentioned conclusion, was provided by the fact that numerous sherds of a pearlware wash basin, found in an ash layer (E.R. 1261B) sealed by the main building's first floor were identical to a single fragment (almost certainly from the same vessel) found in the rubbish pit (E.R. 1255E) postdating the extension's first brick floor. Thus, the first brick paving in the north addition was placed there

Figure 4. Brush - Everard Kitchen

Figure 4. Brush - Everard Kitchen

Second & Third Periods

20

at an earlier date than the first brick floor in this room.

The ash stratum, mentioned above, (E.R. 1261B) immediately covered a thick layer of hard-packed mixed yellow clay (E.R. 1256M) which appears to have served as the kitchen's floor for either or both of its early stages (Fig. 2). Directly beneath this clay flooring, a thin ash layer was found which contained numerous pieces of iron slag. This stratum was found at a level too deep for either period structure; therefore, the iron waste possibly was a by-product of John Brush's gunsmithing operation. If this assumption is valid, the extant kitchen's early stages were non-existent in Brush's time. Additional information, which helps reinforce this conjecture, will be discussed on page 22. Earlier archaeology and the subsequent construction of the south wall, with its massive chimney, has destroyed, unfortunately, any evidence to help determine whether or not the south wall, in its earliest form, could have predated what is now considered to be the first period foundation.

It was mentioned in the introduction that previous architectural studies had indicated that the existing kitchen evolved in three stages. Therefore, before leaving this outbuilding, a notation must be made concerning the physical 21 evidence which substantiates this theory. Portions of the first and second stages of construction (Figs. 3 and 4) exist in the kitchen's west wall. The first period brick foundation (9" thick), originally built to support a frame sill and weatherboarded wall, now bears the weight of the second period brick wall, 1' 1" in thickness, leaving a 4" overhang on the exterior (Plate 6). The first east foundation had been removed entirely and replaced by the second period wall seated on natural subsoil. The extant first period north footing had been cut on its eastern extremity to make possible the erection of the above-mentioned Period II east wall. The severed end on this north foundation suggests the possibility that the first period east wall was not on the same line as that of the second. However, builder's trenches for both east and west walls were found inside the structure, hence, the bricks for both walls should have been laid from the interior. But, the existing second period east wall obviously was built from the outside since the mortar between the interior bricks, which would have been below grade, was not pointed or cleaned. Thus, it must be assumed that the east wall's builder's trench was dug for the construction of the first 22 period's east foundation and not the second. It is established, therefore, that the present width of the kitchen has not changed throughout its existence. The length of the original outbuilding was extended northward a total of 7'11" (Fig. 4) which represents the third and final stage of the kitchen's development. It should be noted that this comparatively small addition was supported by a substantial spread footing, (Plates 6 and 7).

A small fragment of a brown stoneware bottle, found in the kitchen's west wall builder's trench, supplied proof that the structure was built after John Brush's occupation of the property. This sherd cross-mended with others found in an early rubbish pit (E.R. 1269A) outside the west wall. (This pit will be discussed on page 28). The debris-filled hole contained material dating in the period 1725-30 and was cut through by the builder's trench for the first period west wall. Thus, the original kitchen must have been constructed after circa 1730.

Immediately north of the first period structure was found a destruction layer (E.R. 1255Y) containing brick rubble, mortar, and plaster (Plate 8). The brick fragments appeared to be of comparable color and size to those used in the north foundation. The plaster fragments 23 recovered appeared to have come from various areas within the room: i.e. numerous pieces of ceiling plaster, other fragments which had been attached to bricks (presumably from the fireplace), still others which had been affixed to wood (lathe marks present)22a were found. The datable material recovered from this layer indicate a deposition in the mid-eighteenth century which suggests that the first period structure could have been partially torn down at that time.

The above-mentioned stratum yielded the most important archaeological evidence found on this site. As stated earlier, between 1751, when Lots 165 and 166 were sold at public auction, and 1779, when Thomas Everard owned the property, there is no known documentation to prove ownership. However, the recovery of a single decorated delftware plate fragment could put Everard there possibly as early as 1756.

It will be remembered that, in 1745, Everard purchased Lots 263 and 264 on Nicholson Street and eleven years later, in 1756, conveyed the property to Anthony Hay, cabinet-maker.23 The small rim fragment found on the Brush-Everard Kitchen site in a context dated post 1745 (E.R. 1255Y) was identical to pieces of at least three plates found on Lots 263 and 264 in contexts of the period c. 1740-60.24 The fact that these same delftware plates were found on different 24 sites in contexts of roughly the same dates need only suggest that Williamsburg merchants of the mid-eighteenth century stocked this pattern. But, because to date, it has only been recovered from property occupied by Thomas Everard, it may be conjectured that Everard was responsible for their deposition on both sites. If this theory can be accepted, it would seem unlikely that Everard was still using the same plates in 1779 (the first date at which he is known to have been on Lots 165 and 166), after having broken so many dishes from the original purchase at the Hay site before 1756. Reinforcing this improbability is the fact that if Everard had broken the plate after 1779, the artifacts found with it would, almost certainly, have been of comparable date. Therefore, the Research Department's conjecture that Everard purchased Lots 165 and 166 in 1751 and moved there in 1756, when he sold his Nicholson Street property to Hay, appears reasonable. If so, Thomas Everard owned the property for some twenty-five years, including the period that witnessed the construction of the extant kitchen in its present form.

The marl-sealed stratum, which contained the all-important plate fragment, yielded a sizeable quantity of pharmaceuticalia: i.e. fragments of delftware ointment pots, drug jars, and glass medicine bottles. Thus, it appears 25 possible that an apothecary occupied the property in the mid-eighteenth century. The Research Department failed to find documentary evidence to substantiate this conjecture, but it was noted by Dr. Riley that the location of residence and/or shop for a number of apothecaries known to be practising in Williamsburg at that time has not, as yet, been found. Even though proof of an apothecary living on the property in the mid-eighteenth century was not forthcoming, the fact remains that a comparatively large quantity of pharmaceutical artifacts were recovered on Lot 165. These included something in excess of 16 plain white ointment pots, 13 decorated drug jars, 8 glass phials, and one brass pestle. Two of the ointment pots and two of the phials were unbroken.

It may be argued that this apothecary equipment could have belonged to Dr. Gilmer, who owned the lots which abut this property. However, at least two factors seem to make this improbable: 1. The Brush site material was found in an area which would have been screened from the Gilmer property by the kitchen in its first and second phases; 2. Evidence of various fencelines were found separating the Brush-Everard property and Lot 164 and these post holes dated from as early as post 1730 to post 1850 (fencelines are discussed at length on page 29). Therefore, the Gilmer property was

Figure 5. Brush-Everard House Site

Figure 5. Brush-Everard House Site

Colonial and Late Fence Lines - oversized image

| ER 1258B | POST 1750 |

| ER 1258C | POST 1850 |

| ER 1258D | POST 1830 |

| ER 1258E | POST 1750 |

| ER 1258F | POST 1750 |

| ER 1258G | NO FINDS |

| ER 1258J | MODERN |

| ER 1258K | POST 1800 |

| ER 1258L | POST 1750 |

| ER 1258N | POST 1760 |

| ER 1258Q | POST 1770 |

| ER 1258R | POST 1790 |

| ER 1258S | 18th CENTURY |

| ER 1258T | POST 1740 |

| ER 1258V | NO FINDS |

| ER 1258W | NO FINDS |

| ER 1263B | POST 1770 with later intrusions |

| ER 1263D | POST 1785 |

| ER 1263E | POST 1840 |

| ER 1263F | POST 1840 |

| ER 1263H | POST 1770 |

| ER 1263J | 19th CENTURY |

| ER 1263K | POST 1795 |

| ER 1263P | NO FINDS |

| ER 1263Q | POST 1765 |

| ER 1263R | NO FINDS |

| ER 1263S | NO FINDS |

Directly beneath the destruction stratum, a small circular hole (4-½" in diameter) was found (Plate 9 and Fig. 3) cutting through (E.R. 1255Z) a brown artifact-bearing layer. The hole (E.R. 1260G) extended 1'0" into the natural subsoil and seated at the bottom was an intact delftware ointment pot. The object could not have been removed once it was lowered into the hole; thus it would seem more likely to be a product of a child's game than an apothecary's eccentricity. Whether or not the hole predated the kitchen structure could not be determined; however, it would seem to date no later than the mid-eighteenth century.

Numerous features predating the building were found both inside and outside the existing kitchen (Fig. 3), the most curious being a deep, square-sided ditch, 1'5" in width and having an average depth into the subsoil of 1'6-½", filled with mixed yellow clay. This trench (E.R. 1261L) was first discovered outside the northeast corner of the extant extension and later it was found to 27 continue on its NE/SW course beneath all three phases of the kitchen as well as below the existing smokehouse. Time did not permit this feature to be pursued further, though it must be noted that it was not found beyond the aforementioned colonial fence line during the excavation of the north part of Lot 164. Unfortunately, no material was found within the ditch to give it either a terminus post quem or to hint at its original purpose.

The above-mentioned ditch (E.R. 1261L) was cut through by a shallow depression extending north/south which likewise predated the first period kitchen and was found within that structure (Plate 10). This trench (E.R. 1261J) made a right-angled turn to the east at its southern end but soon became confused with the fill of a large natural gully. Another shallow trench (E.R. 1261N) was found 5'1" east of, and parallel with, the depression mentioned above (E.R. 1261J). It is difficult to interpret the original use of these slots (Fig. 3), but it seems possible that they could represent the locations for wooden sills belonging to an earlier outbuilding.

The natural ditch mentioned above (E.R. 1256R) measured 4'0" in width (Figs. 3 and 7) and was filled with dark gray soil, (the iron slag mentioned earlier 28 overlay this fill). This gully was pursuing a northeasterly course beneath and predating all three periods of the extant kitchen. It should be noted also that evidence of this ditch was found on Lot 164, therefore, since a fence line between these lots (164 and 165) was found to date as early as c. 1730 (see page 29), this gully must have been filled in early in the site's history — probably during John Brush's occupancy.

Still another feature predating the existing out-building was discovered between the kitchen's outer west wall and the east wall of the present smokehouse. Beneath a comparatively thin layer of disturbed topsoil, a rubbish pit (E.R. 1269A) was found containing some of the earliest finds of the excavation (Fig. 3). This pit had been cut through by numerous later features including: the afore-mentioned west wall builder's trench for the first period kitchen, the east wall builder's trench for the existing smoke-house, and a deep post hole (E.R. 1269C) in the eastern section of the pit. Upon removal of these later intrusions, the undisturbed trash deposit was excavated.

The artifacts recovered were comparatively few in number, but included the best part of an extremely rare salt-glaze (dipped) pitcher, many fragments of an English brown stoneware bottle (previously mentioned), the better part of 29 a Chinese porcelain tea bowl (cross-mended with a post hole [E.R. 1264R] south of the smokehouse), and numerous wine bottle pieces, all of which dated in the period c. 1725-30. The pit was almost entirely filled with metallic slag and ashes. This fact, coupled with the early datable material almost certainly shows that the deposition occurred during Brush's ownership of Lots 165 and 166. It is curious that the iron waste lacked gunsmithing characteristics. Only two objects found within the pit pertained even slightly to weaponry work, one being a small French pistol flint and the other a brass chape fragment. The large majority of iron waste suggested that Brush (if this debris belonged to him) spent much of his time with general blacksmithing.

As previously mentioned, in the course of excavating areas south of the kitchen and smokehouse, numerous post holes were uncovered (Plates 11 and 12). These belonged to fence lines, extending east and west, that dated from as early as 1725-30 to 1850, or thereafter. The identification of post spacing, for any one period, was deemed almost an impossible task due to the multiplicity of holes in such a small space. Therefore, a map has been drawn showing each post hole with its post quem date in an effort to assist those who may wish to reconstruct the appropriate 30 fence line between these two properties (Fig. 5). The location for the existing fence line (some 20'6" south of the excavated post holes) was deduced by Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Architecture on the grounds that all four lots, east of the Palace Green, should be equal in size. The post-hole-indicated property line appears on the archaeological plan of 1947 and a fence existed there when Lots 165 and 166 were acquired by Colonial Williamsburg. However, after the re-excavation of the First Theatre site in 1947, the fence was moved southward to its present position.

An area, west of the extant north extension, was excavated with the expectation of finding and pursuing the course of the afore-mentioned marl walkway (encountered inside the north addition). However, the grade around the kitchen had been lowered to such a degree that all traces of the marl had been destroyed. The digging in this section was not fruitless since additional fence post evidence was found west and north of the Period I and II kitchen's northwest corner (Fig. 4). Due to the limited time available in which to complete the excavation, these fencelines could not be pursued; however, it was established that they predated the Period III addition. One of these holes contained the remains of a cedar post, as did others found south of the kitchen.

Figure #6. Brush-Everard House Site

Figure #6. Brush-Everard House Site

Features Exposed South of

Excavated Fence Line

In an endeavor to trace the paths of previously mentioned features (the natural gully and the square-sided trench) and also to determine whether or not the pharmaceuticalia found on Lot 165 related in any way to Dr. Gilmer's operation, areas south of what this Department judges to be the colonial property line were excavated. Prior to discussing the features and artifacts found in this area, (Lot 164) that property's pertinent history must be summarized.

Brief History of Lots 163, 164, and 169 From 1716-1770.25

On November 5, 1716, the Trustees of Williamsburg conveyed Lot 164 along with Lots 163 and 169 to William Levingston of York County.26 By 1718, he had constructed at least one building on each lot — possibly including the First Theatre in America (traces of this building were alleged to have been found during the re-excavation of Lot 164 in 1947). The Play House had definitely been built by 1721, for in that year Levingston mortgaged, among other property, Lots 163, 164, and 169, "together with ye bowling green, ye dwelling house, kitchen & playhouse, and all ye other houses outhouses and stables &c thereon" to Dr. Archibald Blair for a period of five hundred years.27 The debt was not paid by December 16, 1723, for on that day Blair foreclosed and took possession of the property and buildings.28

32The next recorded transaction pertaining to this property was dated February 20, 1735, when John Blair, executor of Archibald Blair's Estate, conveyed to George Gilmer "all those Lotts ... designed in Plan of the said City by the Numbers 163, 164 and 169, being the Lotts and Land whereon the Bowling Green formerly was, the Dwelling House and Kitchen of William Livingston and the House call'd the Play House, for the Consideration of the Sum of one Hundred fifty & five Pounds lawfull Money of Virginia ...."29

Gilmer, physician and apothecary, was a respected member of the community and a highly successful businessman.30 He served as one of the city's Aldermen and in 1754 was elected mayor of Williamsburg. His practice must have been lucrative since he was able to send his son to Europe to study medicine, in addition to aiding his former apprentice, William Pasteur, financially while the latter was studying in London.31 In 1752, Gilmer purchased a half-interest in the Raleigh Tavern, presumably, as a business investment.32 It would appear that he was a man of some means and it also seems likely that his practice was one of the more successful in the city.

Williamsburg, even though it was a comparatively small town, had a large number of medical men. In 1735, 33 Governor Gooch wrote that the town abounded with physicians.33 This situation would naturally cause a highly competitive atmosphere. However, the problem was intensified by the numerous druggists and chemists, who usually did not practice medicine but prepared and sold, at low prices, drugs, prescribed by local doctors.34 A dispensing physician like Gilmer would seem to have had an advantage, since most people would prefer to pay one fee for advice and drugs; even so, he must have had a huge volume of business to accumulate his seemingly substantial funds. This conjecture is somewhat reinforced by the fact that the Gilmer property, to date, has yielded more pharmaceuticalia than any other site in Williamsburg.

During the period 1745-1752, Dr. Gilmer repeatedly advertised his merchandise for sale. On June 20, 1745, the following notice appeared in the Virginia Gazette:35

Just imported in the Ship Neptune, Capt. Crawford, from LONDON,The most interesting item in the list is the mention of his 34 selling "Pyrmont Waters" since evidence of this was found during the present excavation (discussed on page 38).

A Large Quantity of Medicines and Druggs, with Annodyne Neclaces, Barleys, Cloves, Mace, Nutmegs, Cinnamon, Sweet Oil, Barber's ditto, Oil of Behn, Prunes, Sago, Stoughton's Elixir, Squire's and Daffy's Elixirs, Bateman's Drops, Lockyer's and Anderson's Pills, Oil-cloth, Scotch Snuff, Goldleaf, and Dutch Metal, Tamerinds, candy's Ginger and Eryngo, Smelling-bottles, Hungary Water, Spaw and Pyrmont Waters, &c. by George Gilmer.

Virginia Gazette, Parks, ed.)

In 1745, Gilmer sold the theatre and six feet of land surrounding it to numerous subscribers who subsequently turned the building over to the city for use as a courthouse.36 The Hustings Court held its sessions in the building until sometime prior to 1770 for on September 27 of that year John Tazewell purchased the land on which the playhouse had stood.37

Dr. Gilmer died in 1757 leaving his Williamsburg property (Lots 163, 164, and 169, except for the area owned by the city) to his eldest son, Peachy Gilmer.38 Two years later, in April 1759, the land was purchased by James Tarpley and Thomas Knox, merchants and partners of Williamsburg.39 Tarpley only kept his share of the land for a year before selling it to his partner, Thomas Knox.40 These men were in the business of importing and selling general merchandise and presumably they purchased the property to pursue this endeavor. At any rate, Knox held the title to the land until August 11, 1764, when John Tazewell purchased it for 450 pounds.41 As previously noted, Tazewell purchased the area (where the First Theatre once stood) from the city in 1770, thus he became sole owner of Lots 163, 164, and 169 35 by 1770.

For the purposes of this report it is not necessary to pursue the chronology beyond this point. But it is important to note that Dr. Gilmer was the only known apothecary occupying Lots 163, 164, and 169 from 1735 to after 1770 and that his business was large enough to necessitate his stocking considerable quantities of vessels (drug pots and jars, medicine phials, etc.) for dispensing his prescribed drugs.

The Archaeology of the Northwest Section of Lot 164

The northern portion of Lot 164 was first excavated in May, 1931,42 and, as previously mentioned, a subsequent archaeological investigation was made in 1947.43 The present limited work, therefore, began with the removal of the back-filling from the earlier test trenches. This chore proved to be unusually rewarding because the trenches had cut through no fewer than five colonial rubbish pits and had subsequently been filled in with the same material (Fig. 6). These finds were valuable additions to the Department's collection but, since they were found in a modern, unstratified trench, they had little archaeological significance.

Fortunately, the rubbish deposits remained undisturbed between the cross-trenches and, in some cases, beneath them 36 (Fig. 6). Near the bottom of the gray loam-filled pit (E.R. 1265E-F) was found a human mandible. A local physician endorsed the Department's conclusion that it had belonged to an elderly Negroid female. The circumstances surrounding its deposition in this colonial rubbish pit will probably never be known.

The datable material found in the above-mentioned pit indicated a deposition of circa 1745. The rubbish in this hole and in the others to be discussed later, included a high percentage of pharmaceutical equipment. This pit alone contained something in excess of 8 decorated delftware drug pots, and 10 medicine phials. It should also be noted that the fill in the previously mentioned natural gully (E.R. 1256R) had been cut through by this rubbish deposit, but the gully's location remained in section on the pit's northeast edge.

Two additional pits (E.R. 1268M and 1268P), found immediately west of the above-mentioned rubbish deposit (E.R. 1265E-F), likewise contained a sizeable quantity of apothecary debris including numerous fragments of delftware drug pots and glass phials. Both pits, filled with brown loam, contained artifacts which indicated a deposition of circa 1745. It should be noted that the pits had been 37 partially disturbed by a wide and deep modern utility trench, as had another deposit (E.R. 1268Q) found north of pit E.R. 1268M (Fig. 6). This hole (E.R. 1268Q) had been almost totally destroyed both by the utility trench (E.R. 1268E) and by a modern archaeological cross-trench. However, the remaining artifacts, including a number of wine bottle fragments, dated in the same period as the other pits, i.e., c. 1745.

Beneath a thin layer of topsoil within the disputed section of Lots 164 and 165, a brick chimney foundation, with a small section of its abutting wall, was found (Plate 13) presumably belonging to a pier-supported structure, since evidence of two piers was encountered north and west of the chimney (Fig. 6). An examination of the mortar showed that it was void of any shell flecks, while the dark loam stratum (E.R. 1268K) which immediately predated the construction of the chimney contained a pearl ware sherd which could date no earlier than c. 1800; therefore, the brickwork must date after 1800 and possibly much later. This foundation had been uncovered in 1947 during that year's excavation but no record had been kept to locate its position. That data has now been added to the current archaeological plan (Figs. 6 and 7).

38The largest and most productive rubbish pit was found beneath the above-mentioned chimney and extending westward from it. Its upper layer (E.R. 1268L), filled with light brown loam, contained quantities of colonial artifacts, including fragments from brown stoneware jars, a single Richard Forte bottle seal bearing the hitherto unrecorded name Rd FORTE, along with more than 169 wine bottle bases. Also present was a large quantity of pharmaceutical material including something in excess of 23 plain white and 27 decorated delftware drug pots, 14 medicine phials and 12 Pyrmont water bottles, all of which dated c. 1745 (Plate 14). This stratum overlay a similar one (E.R. 1268N) filled with sandy brown loam and heavily laden with material dating circa 1745. The recovered objects included, among other items, the better part of a Chinese porcelain plate and bowl, a tin-plated kitchen utensil, 5 straight-stem wine glasses, approximately 350 wine bottle bases, more than 27 delftware drug pots and 8 pharmaceutical phials.

It should be noted that, due to the limited time available, the above-mentioned pit (E.R. 1268L and N) was not completely excavated; however, the artifacts from the productive strata were retrieved, leaving a layer of silty clay in situ. Just north of this pit area, traces of what 39 appeared to be a robbed colonial wall were encountered (Fig. 6) giving rise to a conjecture that possibly the pit may originally have served as a small cellar hole similar in character to that found east of the Travis House.44

The excavation south of the previously mentioned post-hole-indicated fencelines provided great quantities of colonial artifacts. The sum total of the pharmaceutical material found was unusually large, containing something in excess of 92 plain white and 82 blue and white decorated delftware drug pots and jars, and 75 green medicine phials.

The pharmaceuticalia, found in the five pits mentioned above, indicated a deposition of circa 1745, thus dating earlier than that found on Lot 165. As previously noted, Dr. George Gilmer, successful physician and apothecary, owned Lot 164 along with Lots 163 and 169 during the period 1735 to 1757.

Thus, it would seem logical to theorize that Gilmer was responsible for discarding this debris. Reinforcing this conjecture was the fact that pottery sherds found within these pits mended to others, alleged to have been found in holes beneath the First Theatre foundation during the re-excavation of that property in 1947. The fact that no crossmends have been found between this Gilmer rubbish and the 40 finds on Lot 165 weighs heavily against there being any inter-site relationship, and reinforces this Department's conjecture that the present fenceline has been erroneously placed. It seems possible that the five Gilmer pits, dug prior to 1745, were covered over before November of that year, at which time, as previously noted, Gilmer sold the First Theatre building and six feet of surrounding land to the city, since the rubbish deposits would have been quite near (if not on) this public property.

Architectural Evidence Found During the Present Excavation

The destruction debris of a building almost always provides architectural clues which aid in reconstruction planning. The previously mentioned stratum, E.R. 1266Y, rich with brick rubble, mortar, and plaster was no exception. As noted on page 23, the artifacts found within this layer indicated a deposition in the mid-eighteenth century, and it seems likely that the debris represented the partial destruction of the Period I frame kitchen. At any rate, valuable information concerning the outbuilding's interior, prior to 1750, was recovered from this destruction stratum.

The most interesting discoveries from this artifact-laden level were fragments from at least two plain white delft tiles, and others decorated in the more common blue 41 and white patterns. It should be noted that the earlier excavations in the vicinity of the Governor's Palace Kitchen also yielded white tiles suggesting that the interiors of some kitchens may have borne a "somewhat clinical appearance."45

The destruction debris also contained a single fragment of "turned lead" suggesting that the windows may have been of the casement type. It should be mentioned that a quantity of green window glass fragments, which appeared to be the type used in casement windows, was found in the early pit E.R. 1269A just outside the west wall of the Period I kitchen. However, as this pit predated the construction of the early stage of the outbuilding, there would appear to be no connection between the discovery of the "turned lead" and the casement window panes. However, it is possible that subsequent archaeological studies on Lots 165 and 166 will indicate that casement windows were used on Brush's frame dwelling.

The plaster fragments in the destruction stratum, mentioned previously, evidently came from various areas within the kitchen; including the ceiling, frame walls, and the brick fireplace.46 This fact was discussed on page 23, therefore it need only be noted here that, prior to 1750, 42 the inner walls of the kitchen were plastered.

The early pit (E.R. 1269A) between the kitchen's outer west wall and the present smokehouse's east wall not only contained casement window glass (as mentioned above) but also at least five fragments of roofing tile, one of which appeared to have been sooted. Since the material found in the pit dated circa 1725-30, the tile undoubtedly came from buildings erected by the first owner of the property, John Brush. A stone corner fragment (presumably from a mantle) was also found in this iron-slag-laden rubbish deposit. Although this architectural evidence is important, a much larger excavation is needed before these items can be placed in their proper relationship to the building or buildings from which they came.

The five pits, south of the post-hole-indicated fence line, mentioned previously, contained a sizeable quantity of architectural artifacts. These included something in excess of two plain white and 14 blue and white decorated delft tiles and a quantity of roofing tile fragments. Since the First Theatre (the closest building on what this department considers to be Lot 164) is alleged to have had no chimney, the delft tiles must have come from a structure nearer Lot 163. However, as with the Brush pit (E.R. 1269A), 43 additional investigations are required before any deductions can be made concerning their colonial provenance.

Conclusions

The present excavations indicated that the architectural chronology of the Brush-Everard Kitchen was correct; however, it appears unlikely that the Period I frame structure existed in John Brush's time. It was established that the original building had a clay floor and not until the early part of the nineteenth century did a brick floor appear in the Periods I and II structure, although the first brick paving in the Period III addition could have been laid earlier. The extension was probably erected during Thomas Everard's occupancy, although substantiating evidence was not forthcoming. However, it was established that it could not have been built before his time.

The archaeology suggested that an apothecary may have occupied the property in the mid-eighteenth century. In addition, Thomas Everard's presence on Lots 165 and 166 as early as 1756 was deduced from the excavated material, thus tentatively filling documentary gaps in the evolution of the site's history.

The rubbish pits on (what this Department judges to 44 be) the northern part of Lot 164 were vastly rewarding in that they contained the largest and earliest closely dated collection of pharmaceuticalia yet excavated in Williamsburg. The discovery of a portion of a robbed colonial wall points out the need for a thorough re-excavation of Lots 163 and 164 prior to any further reconstruction on that property. Indeed, a similar re-excavation should be undertaken on the Brush-Everard property, as it was proved that a great deal of historical evidence still remains buried there.

It should be noted that the area surrounding the Brush-Everard kitchen was only partially excavated and the conclusions were drawn from the existing research material and the features and artifacts unearthed. Thus, it is obvious that future digging or new-found historical documents could prove some of these theories invalid.

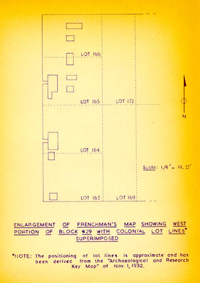

ENLARGEMENT OF FRENCHMAN'S MAP SHOWING WEST

ENLARGEMENT OF FRENCHMAN'S MAP SHOWING WEST

PORTION OF BLOCK #29 WITH COLONIAL LOT LINES*

SUPERIMPOSED

Footnotes

APPENDIX I

Part 1

[July 8, 1717]

[Trustees of Williamsburg

to

John Brush, gunsmith, Williamsburg,

Consideration: 30 shillings current money

of England]"THIS INDENTURE made the eighth day of July in the FOURTH Year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord George... of Great Britain... in the Year of our Lord God One thousand Seven hundred & Seventeen BETWEEN the Feoffees or Trustees for the City of Williamsburgh of the One part & John Brush of the County of York of the Other part WITNESSETH... that whereas... in consideration of Thirty Shillings of Good & lawfull money of England to them [the Trustees] in hand paid... HAVE Granted bargained Sold Remised Released & Confirmed... unto the sd John Brush Two certain Lotts of Ground in the City of Williamsburgh designed in the Platt of the sd City by these figures 165.166. with all woods thereon Growing or being... forever... under the Limitations & Reservations hereafter mentioned... that is to Say that if the sd John Brush his heirs or Assigns Shall not within the Space of Twenty four Months next ensuing the date of these presents begin to build & finish upon each Lott of the sd Granted premises One Good dwelling house or houses of Such Dimensions & to be placed in Such manner as by One Act of Assembly made 23rd of April seventeen hundred and five... then it shall & may be lawfull to & for the Trustees for the Land appropriated for the building & erecting the city of Williamsburgh... to enter & the Same to have again as of their former Estate...

John Clayton (Seal)

[Recorded July 21, 1718

Wil Robertson" (Seal)

York County records,

Deeds & Bonds 3, pp. 246-247]

APPENDIX I

Part 2

[November 26, 1726]

[Will of John Brush, Gunsmith, Williamsburg]

"IN THE NAME OF GOD AMEN, I John Brush of the City of Wmsburgh and county of York Gunmaker... therefore do make & Ordain this to be my last Will and testament...

IMPRIMIS I Give and Bequeath unto my Son Anthony Brush One Shilling Sterling

ITEM I Give and bequeath unto my Daughter Anne Maria Twenty pounds Sterling

ITEM I Will that all my houses and Lots in Williamsburgh do descend Equally unto my Son in Law Thomas Barbar and my Daughter Elizabeth Brush and their heirs for Ever And for their better Agreement I do direct that the same shall (when Either of the Legatees shall require it) by four honest and Indifferent men upon their Oaths be valued and appraised And then if the said Legatees do Agree that Either shall possess the whole I Will that which Possessor shall pay unto the other Legatee relinquishing one half of the Valuation aforesaid by such payments and within such reasonable time as they shall Agree And then the Legatees so possessed shall inherit the said premises to him or her his or her heirs for Ever But in Case of their disagreeing that one should possess the whole as aforesaid or concerning the manner of the payment aforesaid or if the said Legatees shall find it most Conducive to their Advantage to make Sale of the premises or any part thereof In either Case I do direct and impower them or either of them to make such Sale and Sales by good and Sufficient deeds in Law and to Convey the Same as fully & absolutely as I myself might could do if living And that the Produce thereof be Divided Equally between the said Legatees and their heirs respectively

ITEM I Give unto my friend Joseph Davenport of Wmsburgh a Pistole to buy him a Ring

ITEM I Give and bequeath all the rest and Residue of My Estate of what kind soever unto the sd Thomas Barbar and Elizabeth Brush to be Equally divided between them and their heirs Respectively

LASTLY I Do hereby Constitute and appoint the said Thomas Barbar and Elizabeth Brush Executors of this my last Will and Testament hereby revoking all former and other Wills by me heretofore made IN TESTIMONY whereof I have hereunto Set my hand and Seal the twenty Sixth day of November Anno Domini 1726

John Brush (Seal)

50 [torn] blished & Declared to be [torn] tament in presence of us [torn] s Creas, Thos Walker," [Presented in York Court, Dec. 29, 1726 York County records, Orders & Wills #16, p. 424].

APPENDIX I

Part 3

[February 2, 1726/27]

[Elizabeth Brush, spinster, of Williamsburg,

to

Thomas Barbar, carpenter, of Williamsburg

Consideration: [80 current money or one half

value of property]"...WITNESSETH that the said Elizabeth Brush for and in Consideration of the Sum of Eighty pounds Current money to her in hand paid by the said Thomas Barbar... his heirs and assigns for ever all her share of the Messuage or tenement situate lying and being on the north side of the City of Wmsburgh wherein John Brush her father deceased lately dwelt and all Edifices Buildings Goods Tools Yards Gardens... And also those two Lotts containing one acre of ground marked in the platt of the said City with the figures 165. 166. to the said Messuage belonging... which said two lotts were convey'd by John Clayton and William Robertson Trustees for the land appropriated for the building and erecting of the City of Williamsburgh... to the said Brush on July the eighth seventeen hundred and seventeen... TO HAVE & TO HOLD... forever... IN WITNESS...

Thomas Barbar (Seal)

[Recorded York County court

Elizabeth Brush (Seal)"

May 15, 1727

York County records, Deeds 3, p. 470]

APPENDIX I

Part 4

[May 10, 1727]

[Will of Thomas Barbar of Williamsburg, Carpenter]

"...FIRST... I GIVE devise and dispose there of in manner following ITEM whereas I am possessed in fee of Certain lands and tenements in the County of York And whereas my Wife is now Encient of a Child the which if it prove to be a Son My Will is and I do hereby Give devise and bequeath unto Such my [illeg] to his heirs forever ALL my said Lands and tenements (Exclusive of All my Lots and Houses in Wmsburgh which are not intended in this bequest) But in Case that Child prove to be a Daughter Then I Give the said Lands and tenements to be Equally divided in Value (Respect being had to the Improvements) between such my Daughter and my Daughter Judith now living and their heirs for ever ITEM my Will is I do hereby Order and direct that as soon as conveniently may be after my decease My Lots and houses in Wmsburgh be sold by my Executrix to the best Advantage And that the Produce thereof be applied to the payment of my Just debts & funeral Expences, and to my Personal Estate ITEM I Give and bequeath unto my loving Wife Susanna Barbar All my Negroes Cattle Household Goods and personal Estate during her Natural life And that after her decease the said Negroes with their Increase and personal Estate shall descend unto such Child or Children of mine as shall be then living and their heirs or legal Representatives And I do hereby Constitute and appoint my said Wife Susanna Barbar Executrix of this my last Will and testament IN WITNESS whereof I have hereunto set my hand and Seal this tenth day of May in the year of our Lord Christ 1727

Thos Barbar (Seal)

Signed Sealed published & declared to be

[Recorded York County court May 15, 1727

the last Will & testament of ye said Thomas

Barbar

presence of us

Archibald Blair,

Tho: Walker

David Foer"

York County records, Orders & Wills #16, p. 457]

APPENDIX I

Part 5

[November 14, 1728]

[Susannah Brush Barbar, widow and executrix of

Thomas Barbar

to

Elizabeth Russell, widow, York county,

Consideration: £100 current money of

Virginia]"THIS INDENTURE Made the fourteenth day of November in the second Year of the Reign of our Sovereign Lord, GEORGE THE SECOND... and in the Year of our Lord Christ One Thousand Seven Hundred Twenty Eight BETWEEN Susanna Barbar Widdow Executrix of the last Will and Testament of Thomas Barbar late of York County Deceased of the one part and Elizabeth Russell of the Said County of York Widdow of the other part WITNESSETH that Whereas the said Elizabeth Russell by one Certain Indenture of Bargain and Sale bearing date the day before the day of the Date of these presents to her the Said Elizabeth by the Said Susanna made is in Actual possession of the Estate herein after Granted to the Intent that by Vertue thereof and of the Statute for Transferring Use into possession She the said Elizabeth might be Enabled to take and Accept A Release of the Reversion and Inheritance thereof to her and her heirs for Ever THE said Susanna Barbar in pursuance of the Directions of the Said Thomas Barbar in his Testament Afforesaid Contain'd and by Vertue of the power and Authority thereby given her and also for and in Consideration of the Sum of ONE HUNDRED POUNDS of good Current Money of Virginia to her the said Susanna Barbar by the Said Elizabeth Russell in hand Well and Truly paid the Receipt Whereof and herself therewith fully Satisfied and paid She doth hereby Acknowledge and thereof and of Every part and parcel thereof doth Clearly Acquit Exonorate and Discharge the Said Elizabeth Russell... and to her heirs and Assigns for Ever ALL those two Lotts of ground Situate on the East Side of Pallace Street in the City of Williamsburgh Next adjacent to the Governors house and are Numbered in the plan of the Said City by these figures 165, 166 being the Lotts lately held & possessed by John Brush (father of the Said Susanna) deceased and by him... devised... by his last Will and Testament to be Equally divided to and between the said Thomas Barbar and Elizabeth Brush Which Said Elizabeth Brush hath Since Sold & Conveyed her Moiety thereof Unto the Said Thomas Barbar in fee... With ALL houses Outhouses... and FURTHER that She the Said Susanna Barbar her heirs ecus— and Assigns... Shall & will... hereafter within the Space of Seven Years Next hence Ensuing at the Reasonable 54 Request cost and Charges in the Law of the Said Elizabeth Russell her heirs or Assigns Made do and Execute all Such further and Other Reasonable Act and Acts Devises Conveyances and Assurances in the Law Whatsoever for the further better and more perfect Assurance Surety Sure making and Conveying of all and Singular the Above bargained premises Unto the Said Elizabeth Russell her heirs and Assigns for Ever...

[Recorded York County court

Susanna Barbar (Seal)"

November 18, 1728]

APPENDIX I

Part 6

Williamsburg Land Tax records, originals in Virginia State Library Archives; Microfilms, Research Department, CWI.

LOTS VALUATION 1782 John Stith 3 lots £4.10 1783 Thomas Everard Estate 3 4.10 1784 John Stith 3 4.10 1785 John Stith 3 4.10 1786 John Stith ¼ [This is no doubt an error; the line just below is also for ¼ lot] 6.15 1787 John Stith to Doctor Hall 3 9.0 1788 Dr ——Hall to James Carter 3 9.—.— 1789 James Carter 3 12.—.- 1790 James Carter 3 12.—.- 1791 Jas Carter 3 12.—.- 1792 [1793] James Carter 3 12.—.- 1794 James Carter 3 12.—.- 1795 James Carter 3 12.—.- 1796 James Carter 3 12.—.- 1797 James Carter 3 12.—.- 1798 James Carters Est 3 $40 1799 James Carter's Est 3 $40 1800 James Carter's Est 3 $40 1806 James Carters Estate 3 $50 1810 James Carter's Estate 3 $80 1815 James Carters Estate 3 $50 1817 James Carters Estate 3 $80 1819 James Carters Estate 3 $80 1820 Milner Peters Norfolk 1 lot $500; lot & bldgs $525 Heretofore charged to Jas Carters Est. 1821 Milner Peters Norfolk for life 1 lot $500— lot & bldgs $525 1822-1829 [same owner and same valuations] 1830 Dabney Browne 1 lot $500; lot & bldg $520 1839 Dabney Browne 1 lot $600; lot & bldg $800 1846 Dabney Browne Brunswick 1 lot $600; lot & bldg $800 56 1847 Daniel P Custis 1 lot $600; lot & bldg $800 Formerly chd to D. Browne & transfd to Daniel Custis in 1847. 1847-49 same owner and same valuations 1850 Sydney Smith 1 lot $600; lot & bldg $800 From Daniel P. Custis in 1849 1852 Sydney Smith 1 lot $1500; lot & bldg $1800 1857 Sydney Smith 1 lot $1700; lot & bldg $2400 1857-1861 [same owner & same valuations]

[Williamsburg Land Tax records cease in 1861]

APPENDIX I

Part 7

"Mrs Susanna Riddell Dr 1783 February nd 22 To 1250 bricks a 4/ & laying Pathes to kitching & Garden & yard Gates & laying Drane 45/ £4.15.— To Building Well hole in Smoke House 5/ .5.— April th 15 To 600 Bricks a 3/ & 8 Bushels of lime a 1/ 1.6.— To underpining Stable 17/6, & Laying Kitching harth 3/9 1.2.3 To Repairing Cellerwall, & Steps 7/6, & 3 days labour a 3/ .16.6 May d 3 To 1 bushel of mortar 1/3 & Repairing Plastering up Stares 3/ .4.3 To whitewashing 2 Rooms, & a passage a 5/6 .15.6 th 14 To 20 bushels of lime a 1/ & 120 bricks a 4/6 1.3.6 To 3½ bushels of whitewash a 2/ & 6 Days labr a 3/ 1.5.— To whitewashing 4 Rooms, & a Passage a 5/6 1.7.6 To Do 2 Rooms Papered on the Sides a 2/6 .5.— To contracting Chimney & laying the Harth 12/ .12.— To Repairing Plastering in Kitching & Landery 12/ .12.— To 2 Days labour a 3/, & hair 2/ .8.— To lathing & plastering in Closet 5/ & labours work 1/6 & 280 larths .5.— To ½ Bushel of whitewash 1/ (pr Cromwell) .1.— May rd 23 To Cash pd Capt Davis for Frate, & Duty as on Goods 3.0.— Novemr 1 To 22 bushels of lime a 1/ & 300 larthes a 1/6 & hair £13.18.3 9d 1.7.3 To 108 bricks ¾, layg a harth 2/6 & turning Arch & Repairg Chimney 3/6 9.4. To repairing larthing, & plasterg (in Shop) & do in Cellar 18/ .18.— To 4 days labour a 3/ .12.— 1784 April th 4 To 3 bushs of lime 3/ & Repairing Steps 3/9 April 24th, A ballance Due this Day of 38/7 .6.9 25.16.10

1784 July 13 To 2 Bushs of whitewash 4/ & 2½ bushs of lime 2/6 .6.6 To hair 6d to plastering fire place & do in House Landary, & Kitchen 6/ .6.6 58 To Whitewashing 6 Rooms a 4/6, & 2 passages a 5/6 1.18.— To do—Landary 4/6—& labours work 3/ .7.6 Septr 18 To 420 lb of Oats in straw a 6/ pr C 1.5.2 4.3.8 Ms Ledger B of Humphrey Harwood, Research Department, p. 49.

Mrs Susanna Riddell Dr 1785 Octor th 12 To 1½ bushels of lime 1/6 & pointing 2 Chimnies 5/ .6.6"

APPENDIX II

Table of brick sizes removed from Brush-Everard kitchen (and its surrounding area) and preserved

| Location | Measurements | Color |

|---|---|---|

| Period I, north wall [E.R. 1266B] | 9" x 4-3/8" x 2-5/8" | Salmon |

| Period II, east wall [E.R. 1266C] | 8-5/8" x 4-1/8" x 2-5/8" | Dark red to purple |

| Period III, east wall [E.R. 1266D] | 8-3/8" x 3-7/8" x 2-½" | Rich red |

| Period III, first floor [E.R. 1266A] | 9-¼" x 4-3/8" x 2-7/8" (others smaller) | Dark red |

| East chimney [E.R. 1271A] | 8-¾" x 4-¼" x 2-½" | Deep salmon |

| East foundation (abutting chimney) [E.R. 1261B] | 8-¾" x 4-¼" x 2-3/8" | Dark red |

| NE (?) pier [E.R. 1261C] | 9" x 4-¼" x 2-½" | Dark red |

APPENDIX III

| Excavation Register (E.R.) Number | |

|---|---|

| 1255A | Loose dark soil between and immediately beneath the bricks of the top floor in the north extension; post 1820. |

| 1255B | Thin mortar spread with brick flecks beneath top brick floor and, in places, on same level as above; post 1810. |

| 1255C | Reddish soil beneath the mortar spread and immediately covering the lower brick paving within the kitchen's north addition; post 1820. |

| 1255D | Black loam beneath the (above) reddish soil and over a stratum of ashes, and filling spaces where bricks had been removed from the lower floor; post 1820. |

| 1255E | Shallow pit in the center of the north extension, cutting through lower brick floor whose top stratum was filled with black loam as above; post 1820. |

| 1255F | Ash stratum beneath black loam (1255D) and directly covering marl walkway. This layer did not pass beneath lower brick floor; post 1790. |

| 1255G | Ash stratum within pit (1255E) and beneath black loam layer; post 1790. |

| 1255H | Black loam mixed with brick dust and flecks beneath ash layer (1255G) within the shallow pit (1255E); post 1785. |

| 61 | |

| 1255R | Marl spread immediately beneath lower brick floor and cut through at each end by the extension's east and west wall builder's trenches; post 1785. |

| 1255S | Builder's trench for west wall of the period III north extension cutting through marl walkway; post 1750. |

| 1255T | Builder's trench for east wall of the north addition cutting through marl as above; post 1750. |

| 1255V | Hard packed ash stratum beneath and predating marl walkway and directly over burned plaster fragments; mid-eighteenth century. |

| 1255X | Black loam with ash flecks beneath hard packed ashes (1255V) and around plaster and brick rubble; mid-eighteenth century. |

| 1255Y | Destruction layer with plaster, mortar, and brick rubble, beneath black loam with ashes (1255X), mid-eighteenth century. |

| 1255Z | Brown loam with flecks of ashes beneath destruction rubble (1255Y) and over a stratum of gray loam; mid-eighteenth century. |

| 1256A | Thick marl and oyster shell stratum beneath portion of existing upper brick floor located in the southwest corner of the main kitchen structure; last half of the nineteenth century. |

| 1256D | Loosely packed mixed clay with brick and mortar chips around and directly beneath the bricks of the lower floor in the kitchen; post 1790. |

| 1256E | Large rectangular hole, west of the extant reconstructed chimney in main kitchen structure, whose uppermost stratum was filled with ashes; post 1790. |

| 62 | |

| 1256F | Gray sandy loam within hole (1256E) and beneath reddish ash layer; post 1790. |

| 1256G | Charcoal and shell flecked stratum within hole (1256E) directly beneath the above gray sandy loam; no finds. |

| 1256H | Sandy loam within hole (1256E) beneath the above ashy layer, no finds. |

| 1256J | Light brown sandy loam on the bottom of hole (1256E) and beneath the above sandy loam; post 1790. |