Prentis Store, Margaret Hunter Shop, Nicolson Shop, Taliaferro-Cole Shop Architectural Report, Block 18 Building 5 Block 17 Building 4 Block 13 Building 35Williamsburg's Four Original Stores: An Architectural Analysis

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0188

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

WILLIAMSBURG'S FOUR ORIGINAL STORES: AN ARCHITECTURAL ANALYSIS

CONTENTS

| I. INTRODUCTION | 4 |

| II. PRENTIS STORE (BLOCK 18, BUILDING 5) | 18 |

| Abstract | 18 |

| List of Illustrations | 19 |

| Architectural Summary | 22 |

| Notes | 39 |

| Precedents | 42 |

| III. MARGARET HUNTER SHOP (BLOCK 17, BUILDING 4) | 44 |

| Abstract | 44 |

| List of Illustrations | 45 |

| Architectural Summary | 49 |

| Notes | 62 |

| Precedents | 65 |

| IV. NICOLSON SHOP (BLOCK 17, BUILDING 4) | 67 |

| Abstract | 67 |

| List of Illustrations | 68 |

| Architectural Summary | 70 |

| Notes | 87 |

| Precedents | 89 |

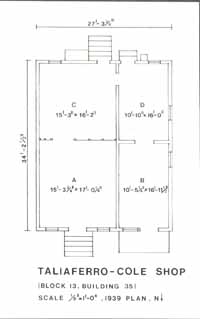

| V. TALIAFERRO-COLE SHOP (BLOCK 13, BUILDING 35) | 90 |

| Abstract | 90 |

| List of Illustrations | 91 |

| Architectural Summary | 93 |

| Notes | 111 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 114 |

INTRODUCTION

In preparing an analysis of the four original store buildings in Colonial Williamsburg, it was necessary to first synthesize the information available on each structure in the research, archaeology and architectural reports and files, as well as the maps and photographs in the Architectural Research Library. A study of the drawing files in the Architects' Office, material from the general files, and the Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn collection in Colonial Williamsburg's Department of Archives and Records supplemented the data. The Audio-Visual Library's photographic collection supplied additional documentation.

Each of the four buildings was examined separately and their physical histories summarized. During the process a number of common characteristics emerged. When considered in conjunction with archaeological data on the stores which did not survive, the four original stores appeared to be examples of a fairly common, but certainly not exclusive, type of building. These similarities and suggested reasons for them are summarized below.

When documentary research and archaeological and architectural investigation for the restoration of Williamsburg began in the late 1920s and early 1930s, researchers identified four original stores or shops. Three are believed to have been built during the second and third quarters of the eighteenth century. These are the Margaret Hunter Shop (Block 17, Building 9), the Prentis 5 Store (Block 18, Building 5), and the Nicolson Shop (Block 17, Building 4). The Taliaferro-Cole Shop (Block 13, Building 35) was essentially a nineteenth-century structure, but it included a late eighteenth-century core which was approximately 18' long and 16' wide. The Hunter Shop and Prentis Store are both one and one-half story brick structures, while the one and one-half story Taliaferro-Cole Shop and the two-story Nicolson Shop are frame.

The process of bringing these structures to their present state of restoration and preservation spanned a forty-four year period. As ownership and functions changed and Historic Area interpretation expanded, two of the stores were altered from rental units to exhibition buildings. The continuing architectural and archaeological research resulted in a progressively more accurate picture of these four commercial structures and revealed a surprising number of similarities in plan and elevation. (See Chart I).

While concurrent research and archaeology at commercial sites in the Historic Area produced additional examples of similarly-sized and sited structures, the investigations also uncovered foundations indicating a variety of sizes and site plans. When the plans, especially those of house-store combinations, are examined more closely, however, dimensions of almost 50% of the commercial units followed the same pattern, that of the narrowest section facing the street. (See Chart II).

For example, James and John Carter built a store with a 41'6" frontage on Duke of Gloucester Street in 1765, but it was divided into two shops, each 20'9" wide and 37' deep. But James Tarpley's and John Greenhow's combination store and house were sited with their longest dimensions on Duke of Gloucester Street. Tarpley's 40' x 34'1" store and house was partitioned on an east-west axis, creating a store room that was only 17' deep. The interior length of the store was estimated at 27' when the building was reconstructed. John Greenhow's 6

| Margaret Hunter (c. 1750) | Prentis (1740) | Nicolson (c. 1760) | Taliaferro-Cole (c. 1782-1830) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Foundation1 | 24'5" x 36' | 24' x 36' | 20'1-½" x 24'3-½" | 26'10-¾" x 34' |

| Shop/Store Room | 21'9" x 17'11" | unknown | 19'0-½" x 19'2" | 15' 3-¾" x 17'0-½" |

| Rear room | 21'9" X 15'6"2 | unknown | 12'6-½" x 13'9" | 16' x 16' |

| Pitch3 | 9'1-¼" | 9'8" | 9' 6-¼" | 8'11" |

| Name (Block and Building) | Dimensions | |

|---|---|---|

| Lightfoot Tenement (3, 23A) | 24'0" x 34'6" | |

| George Jackson House2(7, l4A) | 24'4" x 26'1-½" | |

| Shop | 18'6" x 28'2-½" | |

| David Morton Shop (7, l5C) | 19'11-¾ x 24'0" | |

| Powell-Waller Office (7, 21) | 19'4-½" x 24'0-½" | |

| Isham-Goddin Shop (7, 47) | 13'10-¾" x 28'0-7/8" | |

| Ayscough House (8, 5) | 26'2" x 31'3" | |

| Moir Shop (8, 28) | 32'0" x 20'0-¼" | |

| Draper House (8, 27) | 17'3-½" x 19'11-½" | |

| Shop | 29'0" x 16'2" | |

| Marot's Ordinary East Shop (9, 26B) | 23'0-½" x 16'0" | |

| John Coke Office (9, 27) | 15'4" x 23'10" | |

| King's Arm Barber Shop (9, 29B) | 16'3" x 30'11" | |

| Tarpley's Store (9, 41A) | 40'1" x 34-0-¾" | |

| Brick House Tavern Shop (10, 10C) | 20'7" x 27'7" | |

| Orlando Jones Office (10, 16) | 22'3" x 22'3" | |

| Mary Stith Shop (10, 21) | 16'2" x 24'6" | |

| Mary Stith Tin Shop (10, 21A) | 16'2" x 24'6" | |

| James Anderson House East Shop (10, 22) | 29'7-½" x 20' | |

| 8 | ||

| Peter Hay's Shop (11, 15A) | 40'0" x 22'3" | |

| Greenhow-Repiton Brick Office (13, 20) | 26'10" x 18'8-½" | |

| Boot and Shoemaker's Shop (13, 21A) | 16'2" x 12'9" | |

| John Greenhow House (13, 23E) | 69' x 30'6" | |

| Store | 41'3" x 30'2" | |

| John Greenhow Lumber House (13, 23F) | 40'6" x 21'0" | |

| Taliaferro-Cole Shop (13, 35) | 26'10-¾" x 18' | |

| Dufrey Shop (14, 16E) | 16'2-½" x 24'0" | |

| Nicolson Shop (17, 4) | 20'1-½" x 34'3-½" | |

| Alexander Craig House (17, 5) | 51'6" x 30'7" | |

| Shop | 18'2" x 30'7" | |

| John Carter's Store (17, 7A) | 20'6" x 38'1" | |

| Unicorn's Horn (17, 7E) | 20'6" x 38'1" | |

| Golden Ball (17, 80) | 34'7" x 32'3" | |

| Margaret Hunter Shop (17, 9) | 24'55" x 36' | |

| Prentis Shop (17, 11E) | 32'0" x 16'3" | |

| Pasteur-Galt Apothecary Shop (17, 32) | 20'0-½" x 32'0" | |

| Davidson Shop (18, 1D) | 32' x 32' | |

| Water's Storehouse (18, 3A) | 20'10" x 35'0" | |

| Sign of the Rhinoceros (18, 4C) | 32'2" x 14'9-¾" | |

| Prentis Store (18, 5) | 24' x 36' | |

| Printing Office (18, 12B) | 29'10-¾" x 19'9-½" | |

| Hunter's Store (18, 12G) | 15'10" x 31'7-½" | |

| Holt's Storehouse (18, 28) | 18' 0-¾" x 32'0-5/8" | |

| James Geddy House (19, 11) | 36' x 40' | |

| Shop | 32' x 26'7" | |

| Norton Cole House (19,13) | 53'8" x 37' | |

| Shop | 45'1-7/8" x 19' | |

| 9 | ||

| George Wythe South Office (21, 4A) | 20'0" x 16'6" | |

| Tayloe Office (28, 38) | 16' x 16' | |

| Robertson's Storehouse (28, 24B) | 14'2-½" x 14'0-½" | |

| Hay's Cabinetmaking Shop (28, 72) | 32'3-¼ x 24'3" | |

| Deane Shop (30, 1C) | 22'0" x 16'4" | |

| Forge | 25'0" x 16'4" | |

| McKenzie Apothecary | 22'0" x 17'2"3 | |

With the exception of such larger buildings as Greenhow's, most of the town stores appeared to range in size from 20' to 24' wide and 30' to 34' long. The dimensions were probably influenced by several factors, including the desire to utilize the least expensive framing method, based on the 20'timber span.2 The store's location on the lot, or the amount of lot available, determined whether that 20 feet was the width or the depth of the store.

All of Williamsburg's four original stores presented their narrowest dimension or gable end to Duke of Gloucester Street and all had three-bay facades with central entrance doors flanked by shop windows. This pattern also emerged during field trips and in documentary research undertaken by the Architecture and Research Departments in late 1979 and early 1980.3 Three of the original stores were constructed on properties that were progressively subdivided for their commercial potential. Although the smaller lots may have dictated the size and shape of the buildings, it is equally likely that the property was divided to accommodate a traditional store form. The narrow, gable-fronted store had its origin in English shops of ancient vintage, and the form remained dominant in rural America into the twentieth century.

The merchants buying the parcels of land and planning the shops and stores were influenced as much by English precedents as by the building specifications set forth in the acts of the Virginia Assembly in 1699 and 1705 when the capital was planned. The town act of 1699 stated that persons desiring to buy and hold property on Duke of Gloucester Street, "…shall not build a House less than tenn Foot Pitch and the Front of each House shall come within six Foot of the Street and not nearer and that the Houses in the severall Lots in the main street shall front alike."4 In 1705, the Assembly expanded the code, requiring 11 that builders construct houses 50' long and 20' wide, or 40' long and 20' wide if they had two chimneys and a cellar in order to secure two half-acre lots.5

Since many of the stores were built on lots that had already been secured by previously built, regulation-sized dwellings, it was unnecessary to follow legislated specifications. With all of the houses fronting alike, the narrower gable-end store became visually prominent as a commercial building rather than a dwelling.

The three-bay fronts, built by carpenters who had trained in England or were trained by builders from an English background, were similar to their English counterparts, examples of which can be seen in numerous prints and trade cards of the period.6 But the physical evidence found during the restorations and detailed in the following summaries indicates that the Williamsburg stores did not have the large, elaborate shop fronts which were common to English shops. The necessity of importing glass was possibly one reason for the more modest main elevation. A stronger force, however, was the difference between the English shops and the Virginia store.6a Unlike the shop, which was designed for both the manufacture and sale of a single specialty item or a small group of related items, the colonial store carried a vast inventory of imported merchandise. Elaborate fittings for display would have been of less importance than wall space for shelves, boxes, bins and barrels.

With few exceptions,7 Williamsburg's stores were built over cellars on raised foundations, a logical form since the merchants required extensive storage facilities for their large and varied inventories. The store fronts, consequently, also included stoops of some kind at the main entrance. None of the originals have survived, however, and all have been reconstructed based on archaeological evidence. Three of the cellars were paved. Prentis' and Taliaferro's stores had brick floors, but the millinery shop was paved with flagstone, according to 12 a description in the description in the Virginia Gazette.8

Like dwelling houses, the stores also had cellar windows covered with grilles, and cellar entrances. To facilitate transferring hogsheads, bales, barrels and casks into storage, the entrances at Prentis', Taliaferro-Cole's and Nicolson's were located adjacent to the stoop on the front elevation. The millinery shop now has a cellar entrance on the rear elevation, but the location is conjectural. When the stores were altered or enlarged in the nineteenth century, these entrances, except the one at the Taliaferro-Cole Shop, were closed or relocated.

Although indications of private or rear entrances were obscured in the Taliaferro-Cole and Margaret Hunter shops, the Prentis and Nicolson stores apparently had separate, private entrances. The door of the Prentis Store, located at the northwest corner when the restoration began, may have been closer to an off-center chimney originally. Remnants of a stone stoop indicated that the Nicolson Shop once had a side entrance leading to the stair passage on the west elevation before it was covered by a nineteenth-century wing.

At one time both the Prentis Store and the Nicolson Shop appeared to have had a second floor, or loft, door that was probably used with a hoist for loading barrels or bales of goods to second-floor storage areas. The Prentis Store may have also had another door in the north gable, but the entire wall has been altered several times and it is difficult to determine if this was an eighteenth-century feature.

Despite numerous alterations and restorations, when the framing and brick walls of these stores were exposed for their most recent restoration s, there was enough evidence to determine that all four buildings did not have windows on the front sections of their side walls. Although the west wall of the first section of the Taliaferro-Cole Shop was removed, the east wall was unaltered and there were no signs of windows in the framing. Nicolson's and Prentis' two 13 windows are located towards the back, giving an exterior indication of the interior — a front store room and a back office or counting room. There were no windows on the side walls of the Margaret Hunter Shop.

The rear elevations were the most altered parts of each store, except Nicolson's. At Margaret Hunter's and Taliaferro-Cole's, the rear walls had been completely removed when the buildings were enlarged with rear wings. When the store foundations were excavated or inspected, chimney and stoop foundations and cellar entrances appeared, clarifying the arrangement of the elevations as well as assisting further in establishing plans. Three shops originally had rear chimneys either centered on the gable or off-center toward the side with the windows. The location of the chimney at the Margaret Hunter Shop was conjectural because the first restoration of the north wall in 1930 prevented further investigation of the area.

Some interior evidence augmented the in formation which exterior details provided toward determining the plan. With its original framing and partitions in tact, the Nicolson Shop's two-room plan was clearly evident. The square room at the front served as the store, and the smaller, rear room, also almost square, was probably the counting room. It was located on the east side of the building and the stair passage was on the west. Judging from the location of the windows and the stairs, a similar plan may have existed at the Prentis Store. The original (but not reconstructed) off-center chimney is a further indication of this plan. Although off-center on the exterior, the chimney would have been centered on the north wall of the counting room. Since these buildings were on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street, the counting room may have been planned for the east side to take advantage of the morning light and cooler exposure. The dimensions of the room at Prentis can only be conjectured based on the terminal 14 points of the wood nailers which were set into the interior brick work. Remnants of a brick cross wall in the Margaret Hunter Shop cellar provided the basis for the front room dimension.

The plan of the four buildings appears to be based on providing a square or nearly square front room and, in three cases, a narrower room at the rear.9 This planning feature is significant when correlated with Henry Glassie's observation that the square was the basis for the design of traditional Virginia houses. If partitioned as architectural and archaeological evidence indicates, the Williamsburg stores considered in this report are not unlike Glassie's XY house — one square room plus one room less than square (i. e., an Anglo-American hall-parlor house.)10 Therefore, although the room functions and building orientation differed from domestic models, the builders' spatial conceptualization seems to have been somewhat the same for stores and houses.

The similarity in size and plan can also be attributed to the 20' timber span as well as English precedents, transmitted by tradition as well as by carpenters' manuals. Although Joseph Moxon's manual, Mechanick Exercises (London, 1703), which includes plan s and framing details for a shop, is not documented as being available in Williamsburg,11 Richard Neve's The City and County Purchaser's and Builder's Dictionary (London, 1736) was advertised in the 1764 and 1765 Virginia Almanacks.12 Neve included Moxon's guidelines for planning shop interiors in his section on building. He advised:

…Neither must all Shop keeper's Houses be alike; for some trades require a deeper, others may dispense with a shallower Shop, and for an Inconveniency may arise in both; for if the Shop be hollow [sic] the Front Rooms upward ought to be shallow also; because by the Rules of Architecture all Partitions of Rooms ought to stand directly one over the other: For if the Shop stands in an eminent Street, the Front Rooms are commonly more airy than the Back Rooms, and always more commodious for observing public'd Passages in the Street; and in that respect it will be inconvenient to make the Front Rooms shallow; …1315

Little evidence of interior appointments survived in the four stores, but each buildings' east and west walls, as noted, lacked windows in what would have been the shop or store room,14 suggesting the possibility of built-in shelves or cupboards. All or part of the store room walls of each of the four structures were apparently covered with flushboard, or according to eighteenth-century merchants' descriptions, "ceiled with plank."15 Remnants of original boards were found in the Nicolson and Taliaferro-Cole Shops. The Prentis and Margaret Hunter stores had strips of wood nailers set into their brick side walls. At the Prentis Store two rows of wood strips had been installed in the walls 2' and 6' above the sill and 3' from the ceiling. The nailers in the Hunter Shop appeared intermittently along the wall rather than in continuous strips.

When the Nicolson Shop was stripped, measured and drawn in 1948 prior to its restoration, strips with shelf notching were found behind a later closet at the corner of the east-west partition and the east wall. A pattern could not be discerned, but the notches were apparently for shelves less than 1" thick and very close together.

The Taliaferro-Cole Shop provided the only extant example of shelves in a Williamsburg store. The small bracketed shelves are recorded only in the photographs taken prior to the restoration. They were scattered throughout the nineteenth-century addition, but may have been salvaged from the original shop, like the flushboard.

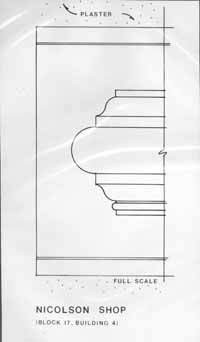

The store room was separated from the counting room and stair passage by a partition. Only the Nicolson Shop had its original partition, and this example retained a glazed door leading to the counting room. This store also offered a glimpse at how a Williamsburg merchant's counting room might have been finished. Sections of a chair rail and a simple architrave mantel survived. 16 Unlike the store room, the office area was plastered. The general appearance was similar to a domestic interior.

By comparing the similar characteristics found in Williamsburg's four original stores, it has been possible to discern that the buildings represented a fairly common type in size and plan based partly on English precedents and spatial concepts, and partly on local building practices. This type, however, must be compared to the archaeological and documentary evidence in order to see that it is by no means an exclusive plan.

Although no evidence remained to assist in drawing conclusions concerning the details of the interior fittings, the large amount of uninterrupted wall space in each store certainly suggests the extent of such fittings. The special needs of the Virginia merchant, whose inventory was large, varied, and often still in packing cases, required a modification of the expensively fitted English shop.

NOTES

I. PRENTIS STORE (Block 18, Building 5)

Abstract of Architectural Summary

The Prentis Store, a one and one-half story brick building with a handsome, pedimented gable end, was built in 1739-40 by John Prentis and Company. Believing at first that it had been constructed after 1760, Colonial Williamsburg restored the structure in 1928 with a classically detailed wooden facade.

During the 1930s, the building was rented to an antique dealer and known variously as the Unicorn's Horn, the Apothecary Antique Shop, and the Colonial Apothecary Shop. From 1940 to 1948, it was the Barber and Peruke Maker's Shop. The building was fitted as the Printing Office in 1948, and was used to interpret that craft until 1957.

When further documentary and architectural research revealed the earlier construction date, a second renovation was planned during the 1960s and carried out in 1972. In addition to changing the wooden frontispiece to a three-bay brick facade, the floor was elevated to its original position level with the water table. The east and west walls, the second floor and roof framing, and the pedimented gable with its modillion cornice, constitute the major portions of original fabric.

The Prentis Store has served as a sales outlet for the Craft Shops since 1972.

ILLUSTRATIONS

| 1. Prentis Store in l927, before it was restored | 24 |

| 2. Prentis Store following the first restoration in 1928 | 27 |

| 3. Framing details for a shopkeeper 's house and shop from Joseph Moxon 's Mechanick Exercises | 30 |

| 4. Elevation of Prentis Store interior walls in 1964 | 33 |

| 5. Prentis Store after the 1972 renovation | 36 |

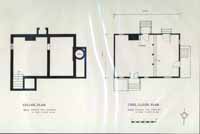

| 6. Cellar and first-floor plans of the restored Prentis Store | 36a |

Historical Background

The Prentis Store was built in 1739-1740 by John Prentis and Company, Williamsburg's oldest and most successful merchant partnership. Constructed to the east of the firm's first outlet on Duke of Gloucester Street, Dr. Archibald Blair's Storehouse, the Prentis Store is the only surviving structure of what was a four-building complex by the late eighteenth century.

The history of lot 46 and the partnership has been well documented in a variety of Research and Archaeology Department reports.1 A brief summary here will be sufficient.

Dr. Archibald Blair, brother of Reverend James Blair, acquired lot 46 in 1700 from the city trustees, but apparently did not build on it as required by law because William Timson received the same lot from the city in 1715. Timson must have built on the property within the allotted two years because when he sold it to James Shield, a tailor, in 1717, the transaction included houses.2 Deeds recorded for the adjacent lot 47 in 1718, however, indicated that Dr. Blair may have been renting the building on lot 46. Although Blair did not appear at this location until 1718, a variety of documentary sources reveal that he was involved in a store with several partners in Williamsburg from 1703 to 1729.3

Blair died in 1733. His son John continued the business, forming a partnership with Wilson Cary and William Prentis. John Prentis served as manager of the firm, which sold a wide variety of merchandise. Their business must have prospered under Prentis because in 1739 the merchants were able to consider constructing another store on the eastern part of lot 46. In the course of 21 building the 24' x 36' brick store, however, Prentis encroached on city property and had to lease a 4' x 36' strip of land adjacent to his lot. The deed was filed in 1743, but was retroactive to 1738/1739 indicating when construction began. The company's stock settlements for 1739, 1740 and 1741 and the date 1740 inscribed in the plaster inside the front gable also corroborate the date of construction.4

When William Prentis died in 1765, the remaining partners selected his son John as manager and the business continued as John Prentis and Company. John died in 1773, only two years after the deaths of partners John Blair and Wilson Cary. The partners' deaths and disruptions in trade resulting from pre-Revolutionary activities caused the remaining stockholders to question the advisability of staying in business. They decided to settle accounts, however, and continue operations. Robert Prentis, a cousin of John and a successful Williamsburg merchant, was appointed manager.5

Robert Prentis' active interest in the store only lasted until 1779, when he began renting the property. In 1783 he left Virginia for Trinidad, placing management of the property in the hands of his cousin Joseph Prentis. His correspondence with his cousin and his nephew William between 1786 and 1804 details attempts to rent or sell the storehouses. The frame store must have been demolished sometime between 1792 and 1800, because Prentis refers only to the store and lot or the brick store in his correspondence. It was certainly gone by 1805 when William Prentis received an inquiry from Dr. William Tazewell, who wished to purchase the vacant lot. The store and lot were finally sold in 1809 to Robert Warburton.6

Merchants continued to buy and sell the building in the nineteenth century. Edward Camm purchased the property in 1850 and used the Prentis Store as a drugstore until he built a new on e on the site of Blair's Storehouse. The 22 Camm heirs owned the property until 1884 when W. W. Vest bought it.

In the deeds of the early 1890s, the store was erroneously referred to as the "Red Lion" and the appellation persevered into the twentieth century. When the property became part of the Williamsburg Restoration, it was first called the Red Lion.7 Until the history of the Blair-Prentis-Cary partnership was fully researched and clarified in the 1950s, the brick store was believed to have been Dr. Archibald Blair' s Storehouse and was called that until 1957.

Archibald Blair's Storehouse

Although the Prentis Store, as one of the four original stores in Williamsburg, is the subject of this report, it is difficult to discuss it without briefly considering the location of the first building on the site — Blair's Storehouse. Documentary and archaeological evidence have provided some knowledge of the structure. The storehouse, as mentioned above, was built near the middle of lot 46. It was probably one of four that Robert Prentis offered for use to the Board of Trade in June 1778 and the one that the Frenchman illustrated as part of the Prentis Store when he drew his map of Williamsburg in 1781. Between 1778 and 1783, Humphrey Harwood, Williamsburg carpenter, performed numerous repairs for Robert Prentis, some of which were done at one of the store buildings.8

Archaeological excavations in 1930 and 1946 revealed the foundation, which measured 32' 6" x 29' 10". Because it was the earlier of the two stores on the lot, there was sufficient room to center the store on the property, unlike the Prentis Store which encroached on city property. The storehouse foundation wall was onn1y 1' 1" thick, indicating that it was probably a frame structure. The cellar floor was paved with brick. Foundations for a separate room approximately 17' long and 7' wide were found in the northeast corner. Because the room was long and narrow and its foundations were l'6-¾" thick, archaeologists 23 believed that the room may have been vaulted. The 1946 excavation also made it possible to determine the location of an interior stair in the northwest corner and a cellar entrance on the east wall. The later had been sealed presumably in 1740 when the brick store was built, and another entrance was constructed on the south wall.9

A third archaeological excavation was undertaken on the site in 1969 to determine the locations of additional outbuildings. A large quantity of early eighteenth-century window glass was recovered with other debris that could be associated with the construction of the storehouse and suggested the possibility of casement windows.10

The 1928 Restoration of the Prentis Store

Colonial Williamsburg acquired the Prentis Store in 1927. Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, architects for the restoration, restored the building in 1928-1929. The building had been modified in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century and the architects were apparently misled by the alterations. (See Illustration #1). They were also hindered by a lack of documentary research on the site and the business enterprise that it represented. Research and architectural reports were not done until twenty years later, in the late 1940s.11 Photographs, a measured drawing, a letter, reminiscences of local residents and the architectural report have provided some insight into what the architects found and what might have influenced their decisions.

When the restoration began in 1928, the basic exterior fabric and plan of the building was intact. A one and one-half story brick structure 36' long and 24' wide, the store was built over a brick-paved cellar 6' deep. The walls are laid in Flemish bond with glazed headers both above and below the water table on the exterior. The pattern of glazing is less regular at the center of the

Illustration #1. Prentis Store in "1927, before it was restored. Neg. Nr. N 3614, Progress Photograph Album 18M, Architectural Research Library.

25

west wall which was blocked from view by Archibald Blair's storehouse. The interior foundations are laid in English bond.

Illustration #1. Prentis Store in "1927, before it was restored. Neg. Nr. N 3614, Progress Photograph Album 18M, Architectural Research Library.

25

west wall which was blocked from view by Archibald Blair's storehouse. The interior foundations are laid in English bond.

The most distinctive feature of the Prentis Store, a substantial pedimented gable end with kicked eaves and a modillion cornice, survived into the twentieth century. Sections of a similar cornice along the east and west walls were also in situ. A rear door and a nineteenth-century central exterior chimney were located on the north elevation. The main entrance and display windows were on the south elevation. In the cellar architects found an existing pier of possible eighteenth-century origin.11a

Sometime before 1920, the first-floor level was dropped and the store windows were lengthened almost to ground level. Panels were inserted above and below sashes. The change required cutting into the water table and disturbing the brick above the windows. Guided by surviving rubbed brick jambs on the outer edges, draftsmen designed a large classically detailed frontispiece. When A. Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne wrote the architectural report in 1949, they cited several plates from William Pain's The Builder's Companion (London, 1762) and The Practical Builder (London, 1788) as precedents. At the time of the restoration, the building's date of 1740 had not been established and the architects 12 believed the shop was post 1760.12

In addition to redesigning the front windows, the restoration also involved installing new windows on the east and west walls. Believing that two bricked-in openings on the east dated from the eighteenth century, the architects reopened these and restored the original north window. To correspond with these openings, a bricked-in aperture in the center of the west wall was also reopened and a new window was added towards the north end, although there was no structural evidence of such a window existing there previously. New cellar windows with segmental arches also without structural evidence, were added to the east and west 26 foundation walls under the north windows. A new window with nine over six lights replaced a nineteenth-century one in the pedimented gable. The existing roof dormers were restored as was the trim and sash on all the windows and doors.13 (See Illustration #2).

According to the 1949 architectural report and a drawing dated November 5, 1928, only a few changes were made to the north wall.14 The door in the north-west corner was retained, but a 2'11" x 6' opening between it and the centrally located chimney was closed. The chimney, which both photographs and an 1828 carpenter's account indicates was nineteenth century, was reworked on the exterior in an eighteenth-century manner. Major restoration requirements on the exterior also included stripping paint from the brick walls, replacing the tin roof with asbestos shingles and repairing and restoring parts of the modillion cornice. A three-step stone stoop was also built to replace the single step stoop.15

At the time of the first restoration, the floor at the front of the shop was slightly above street level, corresponding with the low stoop and the enlarged windows, but the rear portion of the floor was two feet higher and level with the water table. Although the architects believed that this might have reflected the original arrangement, citing floor joist marks in the brick as evidence, one source hints that this may not have been the case. Mrs. Victoria King Lee, in her reminiscences, "Williamsburg in 1861," described the building:

The brick building, across the street from the Barlow House [George Reid House], which has been mistakenly called for years the Red Lion, closely resembles its former appearance, though the interior then was not like it is now.16

Mrs. Lee's memories were recorded in 1933 after the building was restored. The differences she alluded to may have referred to the floor as well as other elements of the interior finishing. The interior was partially restored

with two rooms because, "It was known to have had two rooms on the ground floor…,"17

Illustration #2. Prentis Store following the 1928 restoration. Neg. Nr. N 4230, Progress Photograph Album 18M, Architectural Research Library.

28

according to the architectural report. The front, or south, room was finished as a shop for rental purposes. A display area within the windows was created by framing the recesses with built-in shelves to the east and west, arches and plaster soffits above, and Chinese Chippendale grilles below. The walls were plastered and a vertical flushboard partition separated the front from the rear room which was reached by three steps.

Illustration #2. Prentis Store following the 1928 restoration. Neg. Nr. N 4230, Progress Photograph Album 18M, Architectural Research Library.

28

according to the architectural report. The front, or south, room was finished as a shop for rental purposes. A display area within the windows was created by framing the recesses with built-in shelves to the east and west, arches and plaster soffits above, and Chinese Chippendale grilles below. The walls were plastered and a vertical flushboard partition separated the front from the rear room which was reached by three steps.

Before the restoration, the rear, or north, room included the fireplace and the stairs. Both of these features had been altered. The stair on the west wall was a nineteenth-century addition and the fireplace had been covered. Although a 1928 drawing bears the notation, "repair existing stairs," the 1949 architectural report states that they were "discarded".18 A new fireplace was installed according to local pattern and using old brick. The new wood surround was based on a mantel found at Belle Farm, Gloucester County.

Additional changes in this room included pine sheathing on the west wall, plaster on the north and east walls and the installation of a bathroom between the rear entry door and the stairs. A 6-5/8" chair rail was placed in the room only, but both rooms received cornices and 4-½" baseboards. Four new raised panel doors completed the interior details.19

When the restoration of the Prentis Store was documented in the architectural report by Kocher and Dearstyne, the authors included the paint schedule and established precedents for everything from the two-room plan to the chair rails. Although, "examples of old store buildings in various locations in the Tidewater region and Northampton County were examined for comparison with the Blair Storehouse [Prentis Store],"20 specific stores, unfortunately, were not listed. In addition to architectural evidence, the two-room plan was apparently based on these local sources, other Williamsburg shops (Margaret Hunter and Nicolson) and a shop plan in Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises (London, 1703).21 29 (See Illustration #3). Because the architectural report was written so long after the restoration, it is difficult to determine which precedents were used at the time of the restoration and which were applied after.

Following the restoration in 1929, the Prentis Store was rented to an antique dealer and was known briefly as the Unicorn's Horn. In 1931, it was called the Apothecary Antique Shop and by 1933, the Colonial Apothecary Shop, although the interior was not exhibited as such. After an unsuccessful attempt to equip and furnish the interior as an eighteenth-century apothecary in the late 1930s, the building became the Barber and Peruke Maker's Shop in March 1940.22 The store was used to interpret this craft until 1948. At that time the decision was made to use it to interpret the printing craft. The change necessitated several alterations on the interior including replacing the cross wall with a railing and installing counters in the front room. An eighteenth-century printing press was reproduced and located in the raised rear room.23

The 1972 Restoration

The Printing Office remained at this location until 1957 when it was relocated in the reconstructed Virginia Gazette Office. By this time research and archaeology had clarified the building's role as part of the Blair-Prentis-Cary merchants' partnership and its relationship to the Archibald Blair Store-house, which was no longer standing. Further research and planning began in order to interpret the building as a merchant's store rather than a specialty or craft shop.24

Although the plans which developed for a three-building complex were not implemented, the architectural and archaeological investigations conducted at the store and Blair Storehouse site between 1959 and 1969 revealed additional information about the building. The discoveries made it possible to represent

30

Illustration #3. Plates from Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises (London, 1703), pp. 131, 145, showing framing details for a shopkeeper's house and shop.

31

the building's eighteenth-century exterior appearance more accurately when it was restored again in 1972 for use as a Craft Shops sales area.

Illustration #3. Plates from Joseph Moxon's Mechanick Exercises (London, 1703), pp. 131, 145, showing framing details for a shopkeeper's house and shop.

31

the building's eighteenth-century exterior appearance more accurately when it was restored again in 1972 for use as a Craft Shops sales area.

During a survey of the roof framing in 1959, the architects found evidence of alterations which indicated that the dormers were later additions. Yet, in 1765, the second floor was apparently being used as a chamber according to William Prentis' inventory which listed a bed and bed furnishings in the store. Leroy Phillips and James Knight excavated areas along the north and west foundations in 1959 and found a bulkhead entrance on the north end of the west wall and remnants of a chimney on the east end of the north wall.25

A 1964 investigation revealed that the stairway on the west wall, once located closer to the north end of the building, had been moved forward. Continuous nailers in the brick walls had been cut indicating that the windows added in the 1928 restoration were incorrectly placed. (See Illustration #4). The west wall originally had no windows, a logical plan since it had been built within several feet of an existing structure and would also have been lined with shelves on the interior. Disturbed and patched brick on the north end of the east wall indicated that two smaller windows originally illuminated this part of the store.26

The location of the east wall windows and the easterly orientation of the fireplace suggests that the counting room, an integral part of a merchant's operation, was probably in the northeast corner of the building. The terminal point of the nailers also provides a guide to the location of the room's partition. (See Illustration #4). These discoveries also indicated that the rear door may have been closer to the center rather than directly in front of the stairs, now known to have been approximately 3' to 5' from the north end of the building. An opening that had been bricked up in 1928 may have been part of the earlier door.

32 Illustration #4. Elevation of interior walls of Prentis Store after they were stripped in 1964. Drawn by Steve Yancey, August 1980, from a 1964 measured drawing by Leroy Phillips.

Illustration #4. Elevation of interior walls of Prentis Store after they were stripped in 1964. Drawn by Steve Yancey, August 1980, from a 1964 measured drawing by Leroy Phillips.

When parts of the floor framing and plaster were removed from the east wall, architects found remnants of an unusual, but apparently original, sill on each wall. The 3-½" thick member, which was level with the water table, had been cut back with the brick wall when the floor was lowered, according to notes on the measured drawing.27

The projected second restoration of the Prentis Store included replacing interior fittings, reconstructing the Archibald Blair Storehouse and one outbuilding, and using them to exhibit an eighteenth-century merchant's store. The plan was abandoned in 1972 when a change in ticket and sales policies eliminated the sale of merchandise from the Craft Shops. This created a need for an alternate sales area and the Prentis Store and Tarpley's, on the south side of Duke of Gloucester Street, were selected.28 Only part of the reworked plan for the Prentis Store, which had been drawn in 1966, was implemented. No attempt was made to duplicate the original interior two-room plan or restore the north wall. Some changes, based on research of the past 20 years, were incorporated, however.

The greatest change occurred on the south facade. The late, classical shop front of wood was replaced with a simple three-bay brick facade which included a central double-leaf door with a five light transom. Two sash windows, seven courses above the restored water table, flanked the door. New jack arches surmounted both door and windows. A Flemish bond brick porch with wooden platform, rails and double side steps was initially planned, but during construction in October 1972, evidence of a cellar entrance on the west side of the south wall was discovered. The porch design, with its chamfered posts and beaded rails, was changed to a single side stair and the cellar entrance was rebuilt.29 The window in the gable was replaced with a raised panel door. Kocher and Dearstyne had pointed out the possibility of a door in the gable in their 1949 report, 35 noting that the arch was wider than the window and the brick below was disturbed. The opening was probably used to hoist items into the second floor storage loft.

The two 1928 windows on the east wall were closed, the existing north opening was reduced in width to 2' 8-½" and a second window of the same size was added. The windows were spaced three feet apart. The windows on the west wall and the dormers were not changed. (See Illustration #5).

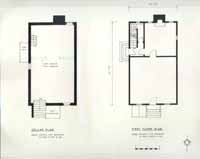

Interior changes were designed to accommodate the sales operation and none of the case work designed in 1966 was used. A one-room plan provided better traffic flow and increased counter and display space. (See Illustration #6). The stairs to the second floor remained in the advance position. Framing around the interior cellar stairway created a partial division on the west side of the store. Although counters of random-width flushboard were installed in front of the east and west walls, the drawers, pigeon-hole units, adjustable shelves and sliding door cabinets were built to display and store merchandise rather than interpret colonial fittings. The units were set into frames with a 3/8" bead. The horizontal flushboard on the north and west walls, and the Belle Farm-inspired fireplace surround were reused. Designed for display, the store windows have shelves on the inside along the muntins. The shelves are supported on ledgers nailed to the window jambs. A rest room and office were built on the second floor.31

The renovation was completed in late 1972. Only a few minor changes have been made to the building since then and it continues to operate as a sales outlet for the Craft Shops.32

Illustration #5. Prentis Store following the 1972 renovation. Neg. Nr. 73-FD-344, Progress Photograph Album 18M, Architectural Research Library.

Illustration #5. Prentis Store following the 1972 renovation. Neg. Nr. 73-FD-344, Progress Photograph Album 18M, Architectural Research Library.

Illustration #6. Cellar and first-floor plans of the renovated Prentis Store. Drawn by Steve Yancey, July 1980.

Illustration #6. Cellar and first-floor plans of the renovated Prentis Store. Drawn by Steve Yancey, July 1980.

N.B. In the following notes, unless otherwise designated, all libraries, departments and offices are in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg, Va.

NOTES

PRENTIS STORE

1928 Restoration Precedents

| Pedimented gable end with kick eaves | Shirley, east dependency | Charles City County |

| Windows | ||

| East and west walls | Carter's Grove | James City County |

| Gable | Mount Airy | Richmond County |

| Dormers | Casey Gift Shop | Williamsburg |

| Chimney Cap | Ferguson Place | Dinwiddie County |

| Bathurst | Essex County | |

| Poplar Hall | James City County | |

| Cornice | Original | Williamsburg |

| End Boards | Original | Williamsburg |

| Frontispiece | William Pain, Practical House Carpenter (London, 1788) | |

| William Pain, Practical House Carpenter (London, 1788) | ||

| Rear Door | Shield House | Yorktown |

| Trim | Tabb House | York County |

| Casey Gift Shop | Williamsburg | |

| Barraud House | Williamsburg | |

| Back Porch Rail | Farmington | Charles City County |

| Storeroom | ||

| Arched window recess | Tuckahoe | Goochland County |

| Wilton | Middlesex County | |

| Belle Isle | Lancaster County | |

| Chippendale Grille | Weyanoke | Charles City County |

| 43 | ||

| Cornice | Bassett Hall | Williamsburg |

| George Reid House | Williamsburg | |

| Baseboard | "conventional design" | Virginia |

| Door to rear room | Peyton-Randolph House | Williamsburg |

| Trim | Casey Gift Shop | Williamsburg |

| Rear room | ||

| Fireplace | ||

| Surround | Belle Farm | Gloucester County |

| Hearth | Williamsburg examples | Williamsburg |

| Walls of horizontal flushboard | Market Square Tavern | Williamsburg |

| Marmion Outbuilding | King George County | |

| Chair Rail | Dado cap | Delaware |

| Baseboard | "conventional design" | Virginia |

| Doors to stairs, cellar, restroom | Peyton-Randolph House | Williamsburg |

| Trim | Casey Gift Shop | Williamsburg |

| Cornice | Bassett Hall | Williamsburg |

Source: A. Lawrence Kocher and Howard Dearstyne, "Archibald Blair's Storehouse (Block 18, Colonial Lot #46)," Architectural report, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1949.

II. MARGARET HUNTER SHOP (Block 17, Building 9)

Abstract of Architectural Summary

The Margaret Hunter Shop, a one and one-half story brick building with weatherboard gable, was probably built by the mid-eighteenth century. The shop was restored in 1930 with large shop windows, a porch and a rear wing. The east and west walls and the foundations are the only original features. It was rented to the Pender Grocery Company until 1937 when it became the Golden Ball. In 1951, the Golden Ball was relocated to its original site and the building was restored to one of its original functions — an eighteenth-century milliner's shop. The classical wooden facade, the porch and the rear wing were removed and the entrance was elevated to its original level at the water table. The Margaret Hunter Shop opened in January, 1954, and has not been altered since.

ILLUSTRATIONS

| l. Margaret Hunter Shop in the 1920s,before the first restoration | 50 |

| 2. Margaret Hunter Shop after the first restoration in 1930 | 50a |

| 3. Shop windows and glazed door of the Prentis Store in an 1889 photograph | 52 |

| 4. Shop windows sketched in a 1743 trespass suit | 52a |

| 5. Interior east wall of the Margaret Hunter Shop showing nailers | 55 |

| 6. Elevations of east and west walls showing distribution of the nailers | 55a |

| 7. Margaret Hunter Shop in 1953,after the second restoration | 56 |

| 8. Cellar and foundation plans of the restored Margaret Hunter Shop | 56a |

| 9. Millinery Shop interior in 1954 | 58 |

| 10. Eighteenth-century English shop interiors | 60 |

| 11. Corner cupboard from Hillsborough | 60a |

Historical Background

The Margaret Hunter Shop, first restored by Colonial Williamsburg in 1930 for rental purposes and again in 1952 as an exhibition building, was possibly built between 1735 and 1755. Although the first owner of lot 52, Samuel Cobb had improved the property by 1736 when he sold it to merchants John Harmer and Walter King, there is no evidence that either owners built l the brick and weatherboard millinery shop.1

Harmer and King conducted business at this location from 1736 to 1746 according to advertisements in the Virginia Gazette. In 1745, and again in 1746, the merchants tried to sell "The Dwelling House, Out Houses, and 2 Store Houses, etc. in the main Street, opposite Mr. Wetherburn's."2 The public sale must have been unsuccessful because Harmer sold "All that messuage 3 and lot of ground … denoted by the numbers 52 … "3 to his partner King in November 1746.

Sometime between then and 1755 Walter King transferred the property to Dr. George Gilmer, Sr. Dr. Gilmer listed "the brick store and house" as a legacy to his son George Gilmer, Jr. when he recorded his will in 1755. Gilmer, Jr. inherited the property in 1757 when his father died.4

Gilmer's brick store did not become a millinery shop until the late 1760s. On October l, 1767, Jane Hunter placed the following advertisement in the Virginia Gazette:

The subscriber having a sister just arrived from London, who understands the millinery business, she hopes to carry it on to the satisfaction of 47 those who shall favour them with their commands. They have imported all the materials for making hats and bonnets, in the newest taste; where Ladies may be supplied on the shortest notice, byThe assumption that Jane Hunter was conducting business at this location in 1767 is also based on a later deed which refers to her earlier occupancy. Although Miss Jane Hunter concluded a deed of lease with Dr. Gilmer in 1770 for part of lot 52, by 1774 her sister Margaret was named as owner of the eastern part of the lot in related deeds. Periodic references in source material from 1780 until 1787 indicate that Margaret was sole owner of the 6 lot and brick building.6

Their humble servants,

M.& J. Hunter.5

Margaret Hunter died in October 1787. Her property, advertised for sale on October 11, 1787 in the Virginia Gazette and Weekly Advertiser, was described as follows:

THE BRICK HOUSE the property of the late Mrs. Hunter, situated in the most public part of the city, well calculated for a store or dwelling house, in very good repair, it has a flush cellar, laid with flag stones, and a very convenient kitchen …

Court records of 1795 reveal that Margaret's two sisters, Jane Charlton of Williamsburg, who must have left the business upon marrying, and Elizabeth Farrow of London, were joint heirs of the property. Jane Charlton purchased Elizabeth's half interest in 1795 and insured her brick buildings the following year.7

From the time that this first policy was written in 1796 until 1843, the Mutual Assurance Society revalued the same buildings (shop and kitchen ) seven times for a series of clients. Each policy describes a one-story brick house, dwelling and/or store covered with wood on Main Street with a two story kitchen behind. Although two policies give the dimensions as 27'x40', the 48 most consistent ones appear to be 24'x36' for the house and store and l6'xl6' for the kitchen. Mrs. Stephenson attributes the variations in size to carelessness on the part of the appraiser rather than on changes in the buildings.8

The policies also reveal that the brick building continued in use as a store for at least the first half of the nineteenth century. Although the two earliest policies (1796 and 1806) describe the building simply as a brick house or dwelling house, policies dated 1815, 1817, 1823, 1830, 1839 and 1843 describe it as a dwelling and a shop or store. By 1830, when Nicholas, Vest & Co. owned and occupied the property, the brick building was described as a two-story store and the wood kitchen to the north or rear of the shop was designated a store house.9 The 1839 and 1843 policies, however, list the brick store on Main Street as one and one-half stories. These inconsistencies in dimensions and numbers of stories have made it difficult to determine when the store was enlarged to the longer, two-story structure which Colonial Williamsburg acquired in 1930. The reminiscences of Williamsburg citizens recorded between 1929 and 1933 helped to eliminate the confusion.

According to both J. S. Charles and Mrs. Victoria M. Lee, the structures served as a store and dwelling in the 1860s. In describing the buildings on Main Street as he remembered them before the Civil War, Mr. Charles stated, "The next building was the brick house now used as an auto shop. This is a very old building, the first floor of which was much higher than at present, reached by stone steps leading up from both sides in front; it was used for a store and a residence."10 Mrs. Lee, who moved to Williamsburg in June 1861, noted, "Beyond the Lee House was a two story brick store kept by Mr. Teiser. This building has now been restored and is called the Kinnamon Store."11 Mrs. Lee's description indicates that by 1861, Margaret Hunter's Shop, or Kinnamon's Store, as it was called in the 1920s and 1930s, had been enlarged to two stories.

The 1931 Restoration

As an eighteenth-century structure, the shop was one of the earlier buildings to be restored by Perry, Shaw and Hepburn. When the Williamsburg Holding Corporation acquired the combination store and auto shop in 1930, the colonial structure had been lengthened on the north (rear) side, the walls had been raised to two stories and one window opening on the front elevation had been enlarged to create a garage door.13 (See Illustration #1). The original dimensions of the wall on the east side were evident, however, as was the eaves line.

While studying the structure and planning its restoration, the architects noted that the overall dimensions were the same as the Prentis Store, then known as the Red Lion Inn, and that the east and west walls showed no signs of windows.14 A remnant of the north foundation wall found in the east corner verified the original 36' length of the building reported in the insurance policies.15 Although the gable end on the second floor of the sound elevation was brick, it was laid in common bond indicating that it was of a later date. With this evidence, the architects made the decision to replace the front gable with weatherboard.16 (See Illustration #2).

Exterior details, such as trim, windows, doors, etc. , were restored or reconstructed based primarily on local precedent. Although the precedents were not recorded at the time of the restoration, reports written in the late 1940s by individuals who had been associated with the architecture department in the early 1930s failed to provide more specific design sources. The glazed front door with its five light transom and the two new shop windows as well as the cornice, the second floor gable window, the dormers, the end

Illustration #1. Margaret Hunter Shop in l930, before the first restoration. Neg. Nr. S-1279-GN, Progress Photograph Album 17E, Architectural Research Library.

Illustration #1. Margaret Hunter Shop in l930, before the first restoration. Neg. Nr. S-1279-GN, Progress Photograph Album 17E, Architectural Research Library.

Illustration #2. Margaret Hunter Shop after the 1930 restoration with a front porch and rear wing Nr. H-453, Progress Photograph Album 17, Architectural Research.Library.

51

and the corner boards were all based on "local colonial design." All of the trim-was reproduction and the necessary brick work, such as that for the new north wall, utilized antique brick, which the Restoration had collected from demolished structures in Tidewater Virginia. There was no evidence of a chimney, but a new one was built following local design.17

Illustration #2. Margaret Hunter Shop after the 1930 restoration with a front porch and rear wing Nr. H-453, Progress Photograph Album 17, Architectural Research.Library.

51

and the corner boards were all based on "local colonial design." All of the trim-was reproduction and the necessary brick work, such as that for the new north wall, utilized antique brick, which the Restoration had collected from demolished structures in Tidewater Virginia. There was no evidence of a chimney, but a new one was built following local design.17

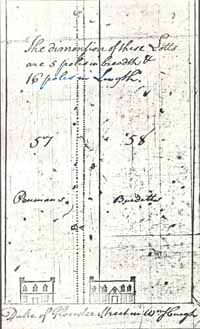

In 1948, the staff of the architecture department held a meeting to discuss the Margaret Hunter Shop (then known as Kinnamon's Store) and establish more specific precedents. Acknowledging that many of the elements of the building were inaccurate, Singleton P. Morehead, A. L. Kocher and Howard Dearstyne stated that other portions could be related to specific buildings in Virginia and in eighteenth-century publications. Morehead felt that the shop windows were similar to those illustrated in a pre-1900 photograph of the Prentis Store, then called the Wig Shop. (See Illustration #3). The photograph was part of the Cole-man Collection, a group of 100 photographs, taken by Charles Coleman between c. 1885 and 1922 and donated to Colonial Williamsburg in 1950. A sketch made of two taverns (Burdette's and Penman's ) on colonial lot 57 and 58 for a trespass suit which appeared in the York County records of 1740-1746 also revealed similar show windows. (See Illustration #4). The glazed front door also followed the Prentis Store precedent and was supplemented by Plate 25 in the 1748 edition of Salmon's Palladia Londinensis.18 The door and window trim was based on that from a basement window at the Tabb House in York County, Virginia.19 The Coke-Garret House in Williamsburg provided a precedent for the new chimney.20

When Kinnamon's Store was restored in 1930, there was no information available at the time on the colonial appearance of the interior. Because the shop's intended use was for rental purposes rather than for exhibition, the interior finish was plainly done. Plaster walls, bases and the enclosed stair were reconstructed in a "colonial manner," and several of the interior doors were the six panel colonial stock items. Although the interior was entirely

Illustration #3. Prentis Store in 1888-89, showing shop windows and glazed door. Neg. Nr. L299, George Washington Coleman Photograph Collection, Album 1, Architectural Research Library.

Illustration #3. Prentis Store in 1888-89, showing shop windows and glazed door. Neg. Nr. L299, George Washington Coleman Photograph Collection, Album 1, Architectural Research Library.

Illustration #4. Copy of a drawing in a 1743 trespass suit between Penman and Burdette recorded in York County Records, Wills and Inventories, 1740-1746, p. 209.

53

built on the eastern side of the partition. Two additional shelves, 12" and 18" deep were placed on the east wall behind and above a counter from antique storage.28

Illustration #4. Copy of a drawing in a 1743 trespass suit between Penman and Burdette recorded in York County Records, Wills and Inventories, 1740-1746, p. 209.

53

built on the eastern side of the partition. Two additional shelves, 12" and 18" deep were placed on the east wall behind and above a counter from antique storage.28

The sources for the moldings, brackets and profiles of the shelves as well as their placement were not recorded, but one possible precedent appeared for an additional unit of hanging shelves designed for the west wall in 1937. This three-shelf unit featured a cut standard (vertical side supports) which may have been based on hanging shelves at Carter's Grove and Toddsbury.29

The Golden Ball had only been open several months when the disparity between Rieg's modern work and the craft shop work required the addition of another partition to screen from view non-colonial objects and tools. When the 6' x 10'11" partition was installed, shelves were attached to both sides. This solution was short-lived, however, as Rieg became more involved in explaining his craft. In 1942 his request that the screen be removed was granted and the shelves from it were relocated to the east wall.30

By 1941 the Research Department had located the site of the original Golden Ball on Duke of Gloucester Street. The jeweler's shop, operated by James Craig from c. 1765 to c. 1779, once occupied the lot immediately to the east of Margaret Hunter's Shop. When the decision was made in 1948 to reconstruct James Craig's Golden Ball on lot 53, planning began for an authentic restoration of the millinery shop as an exhibition building. Development proposals on lot 52 also included the accurate reconstruction of several out-buildings, including a workshop, the foundations of which were revealed in a 1939 archaeological investigation.31

The 1952 Restoration

Max Rieg vacated the first Golden Ball in July, 1951. Architectural investigation of the interior began soon afterwards. After removing the 1930 plaster from the interior walls, the architects were able to inspect the colonial brick and found antique nailers as well. (See Illustrations #5-6) . The wood was arranged in a manner which suggested the possible presence of a dado, shelves and paneling on the east and west walls. The inspectors also found floor joist sockets 19-½" above the 1930 floor, confirming Mr. Charles' description.32

Changes on the exterior during the restoration involved removing the unauthenticated rear wing and the front porch. Using the Charles' recollections as precedent, a new brick stoop with double side steps, stone treads and platform and a wrought iron railing were built. Details in the railing design were the same as those used for the Robert Carter House porch when it was restored. The shop windows were raised to a level five courses above the water table and surmounted by new jack arches. Because the windows remained the same width, it was unnecessary to alter the adjacent piers which had been restored in 1930. (See Illustration #7). After the rear addition was demolished, a new cellar entrance 15" wider was built and new steps were provided for the rear door on the northwest corner, which also had to be raised to align with the higher floor. Panel shutters were placed on either side of the second floor gable window.33

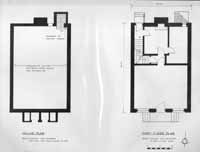

The restoration of the shop interior required designing fittings and spaces that would aid in interpreting an eighteenth-century milliner's establishment and that would also provide office space for the costume and dressmaking division (See Illustration #8). The kitchen behind the shop, mentioned in the Virginia Gazette advertisements, was reconstructed as a workshop for that division.

Illustration #5. Interior east wall of Margaret Hunter Shop showing nailers in wall. Neg. Nr. 52-T-488, Progress Photograph Album 17E. Architectural Research Library.

Illustration #5. Interior east wall of Margaret Hunter Shop showing nailers in wall. Neg. Nr. 52-T-488, Progress Photograph Album 17E. Architectural Research Library.

Illustration #6. Distribution of nailers on the east and west walls of the Margaret Hunter Shop. Measured drawing by Steve Yancey, July 1980, based on architectural field notes made in 1952.

Illustration #6. Distribution of nailers on the east and west walls of the Margaret Hunter Shop. Measured drawing by Steve Yancey, July 1980, based on architectural field notes made in 1952.

Illustration #7. Margaret Hunter Shop in l953,after the second restoration, except for signs and shutters. Neg. Nr. 53-M-2003, Progress Photograph Album l7E, Architectural Research Library .

Illustration #7. Margaret Hunter Shop in l953,after the second restoration, except for signs and shutters. Neg. Nr. 53-M-2003, Progress Photograph Album l7E, Architectural Research Library .

Illustration #8. Cellar and foundation plans of the Margaret Hunter Shop restored. Drawn by Steve Yancey, July 1980.

Illustration #8. Cellar and foundation plans of the Margaret Hunter Shop restored. Drawn by Steve Yancey, July 1980.

A new east-west partition on the south side of the stairs divided the first floor of the Hunter Shop. This provided an exhibition space measuring approximately 18' x 21' in the south half of the shop and two offices and a research room in the north half. The previously unfinished second floor became a sewing and storage room.34 All of the store and office fittings were new with the exception of the front door and the stairs, which were only given a new wall string and winders.

The shop fittings, centered on a glazed door and three light transom in the partition, are arranged in a block C plan. (Illustration #9). They include a balanced series of framed shelves, drawers, corner cupboards and counters behind a C-shaped floor counter. The units face the show windows and door on the south elevation, providing a logical arrangement for interpreting the function of the shop to the visitors. The open shelf sections flanking the door are 3'4" wide and have three beaded edge shelves each over a counter and lower cabinet. They are enclosed in frame with cyma reversa corner brackets and cornice. A column of six drawers 1'5" wide and 10" deep with center pulls separate the shelves from the corner cupboards. Each cupboard has a single glazed door with four rows of two lights each and a fanlight. The lower half of the cupboard includes a drawer and two doors. An additional section of framed shelves and drawers complete the system on the east and west walls.35

The walls throughout the shop area are covered with random width flushboard, shiplapped and beaded. The lower portions, which are not fitted with counters and cabinets, are paneled with a dado. Two open shelves were p 1 aced above the dado on the west wall. Each 5' 9" shelf is supported by three truss brackets and chamfered braces. A more elaborate hanging case was de-signed for this space on the east wall. Built of walnut and yellow pine, the two-door cabinet is 6' wide, 3'5" high and 9'15/16" deep. Each door is two

Illustration #9. Interior of the millinery shop after the 1952 restoration. Neg. Nr. 54-W-262, Millinery Shop Current File, Audio-Visual Library.

59

lights wide and four high. A bracketed shelf was placed above the cabinet. As a final exhibit space, three slant front glass-topped counter cases were designed for the floor counters. Precedents for glass cases or presses can be found in York County Inventories and Virginia Gazette advertisements of the eighteenth century.36

Illustration #9. Interior of the millinery shop after the 1952 restoration. Neg. Nr. 54-W-262, Millinery Shop Current File, Audio-Visual Library.

59

lights wide and four high. A bracketed shelf was placed above the cabinet. As a final exhibit space, three slant front glass-topped counter cases were designed for the floor counters. Precedents for glass cases or presses can be found in York County Inventories and Virginia Gazette advertisements of the eighteenth century.36

The architects used several specific precedents in designing the eighteenth-century shop interior. The general use of counters, cases and interior sash doors was derived from illustrations in A. E. Richardson's Georgian England. Figure 18, drawn from a trade card, shows a milliner's shop interior with a counter, an interior shop door leading to a heated room, a hanging glass-doored cabinet.37 (See Illustration #10).

Several Virginia cupboards provided the profiles for cornices, counter edges and muntins. A cupboard owned by Dr. W. L. Smoot of Miller's Tavern, Va., was used for the wall counter edge and a cupboard at the Raleigh Tavern provided the cornice profile. The muntins in the corner cupboards were patterned after those in a similar case piece at Hillsborough in King and Queen County, Virginia. The fan light may have also followed the Hillsborough example even though it was not specifically noted on the drawings. (See Illustration #11). The door and window trim was designed from a fragment in the miscellaneous assortment at the warehouse.37

The Margaret Hunter Shop opened officially as an exhibition building 38 on January 25, 1954, during the Antiques Forum.38

Few changes have been made in the building since 1954. After the costume department vacated the back offices and workshop in the early 1960s, the area behind the door was arranged as an extension of the exhibit area with additional furnishings and millinery samples. The plate glass covering the open shelves was replaced with a non-reflecting and screening plexiglass

[London shop interior.]

[London shop interior.]

Illustration #10. Shop interiors illustrated in A. E. Richardson's Georgian England (New York, 1931), p.67.

Illustration #10. Shop interiors illustrated in A. E. Richardson's Georgian England (New York, 1931), p.67.

Illustration #11. Corner cupboard at Hillsborough in King and Queen County, Va. Photographed by HABS, n.d. Virginia Buildings Files, Architectural Research Library.

61

to protect the period textiles and milliner's accessories from ultra-violet rays. The interior was repainted in 1973, changing the color from a predominantly green color scheme to a simulated whitewash with beige trim to brighten the interior.39

Illustration #11. Corner cupboard at Hillsborough in King and Queen County, Va. Photographed by HABS, n.d. Virginia Buildings Files, Architectural Research Library.

61

to protect the period textiles and milliner's accessories from ultra-violet rays. The interior was repainted in 1973, changing the color from a predominantly green color scheme to a simulated whitewash with beige trim to brighten the interior.39

NOTES

MARGARET HUNTER SHOP

(Block 17, Bldg. 9)

Precedents1

| Exterior | |

|---|---|

| Shop Windows | -Burdette's & Penman's ordinaries, sketch in York County Records, 1740-1746, p. 209. |

| -Prentis Store, Coleman Collection Al bum #1, Neg. Nr. L299. | |

| Glazed front door | -Prentis Store, do |

| -Salmon Palladia Londinensis, plate 25. | |

| Transom | Local colonial design |

| Gable window | " " " |

| End board | " " " |

| Corner board | " " " |

| Chimney | " " " |

| Door and window trim | " " " |

| Interior | |

| Plaster walls | Local Colonial design |

| Bases | " " " |

| Stair | " " " |

| Door | " " " |

| Exterior | ||

|---|---|---|

| Porch | J. S. Charles' "Recollections of Williamsburg." | |

| Railing | Robert Carter House | Williamsburg, Va. |

| Door and window trim | Warehouse fragment | " " |

| 66 | ||

| Interior | ||

| General plan | A. E. Richardson's Georgian England (New York, 1931) | |

| Corner cupboards | Cupboard, Hillsborough | King & Queen County, Va. |

| Graeme Park | Horsham, Pa. | |

| Counter edge | Cupboard, D. W. L. Smoot | Miller's Tavern, Va. |

| Cornice | Cupboard, Raleigh Tavern | Williamsburg, Va. |

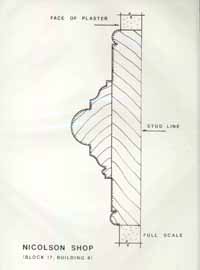

III. NICOLSON SHOP (Block 17, Building 4)

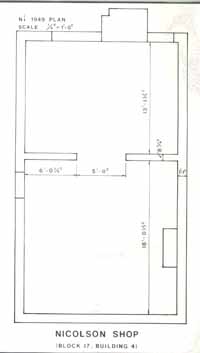

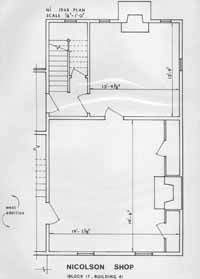

Abstract of Architectural Summary

Built during the third quarter of the nineteenth century, the Nicolson Shop was a two-story frame store located on the north side of Duke of Gloucester Street. Although the shop was incorporated into a domestic dwelling by 1843, the framing, floor plan, and some interior trim survived. When Colonial Williamsburg restored the building in 1949-50, the nineteenth-century wing was removed making it possible to reconstruct the south elevation in its original three-bay, gable end form. The interior restoration, while planned for residential use, preserved the original floor plan and trim. Of the four original stores in town, the Nicolson Shop retains the most eighteenth-century fabric, including the only surviving interior glazed door in Williamsburg.

| 1. Nicolson Shop in the l920s, when it was part of the Lee House | 71 |

| 2. Foundation plan of the Nicolson Shop in 1948 | 73 |

| 3. First-floor plan of the Nicolson Shop before the restoration | 75 |

| 4. Original interior glazed door | 75a |

| 5. Elevation of shelf notches found in the Nicolson Shop in 1948 | 78 |

| 6. Salvage flushboard on the nineteenth-century stairs | 78a |

| 7. First-floor north fireplace | 79 |

| 8. Section of chair rail found in north room | 79a |

| 9. Elevation of chair rail found in stair passage | 80 |

| 10. Nicolson Shop in l950, following the restoration | 84 |

| 11. Cellar and first-floor plans of the restored Nicolson Shop | 84a |

Historical Background

Located on an eastern portion of colonial lot #56, the Nicolson Shop on Duke of Gloucester Street was probably built during the third quarter of the eighteenth century. Title transfers do not specifically mention buildings on the site until 1760, but several merchants owned the property and it doubled in value between 1749 and 1760.1 Tavernkeeper Henry Wetherburn purchased the property in 1749 for 95 pounds and sold it and "all houses, outhouses, yards, 2 [and] garden…" in 1760 for 200 pounds to Dr. William Pasteur.2

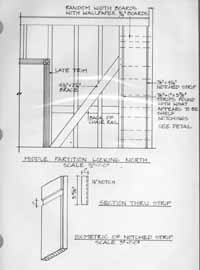

Dr. Pasteur subdivided the property still further within a few days of his purchase, selling a section 30' x 87' which fronted on Duke of Gloucester Street to Robert Miller and Co., merchants, and a rear portion 30' x 177' to William Holt, merchant. Both titles listed "all edifices, buildings, yards and appurtenances." Robert Nicolson purchased Miller's and Holt's properties in 1773 and transferred both to his son William in 1779.3 In that same year, and again in 1782, Williamsburg builder Humphrey Harwood posted the following charges to William Nicolson in his ledger:

4

1779 Octobr… Novemr 13 To 60 bushls of lime 12/ & 3900 bricks a 16.10, & 12 days labr a 24/. ll4.15.- To Carting 3 loads of Sand a 20/ To pillering Shop 10. 0. 0 13. 0. - To building Shop Chimney 36. 0. 0 1782 May 9 To whitewashing 2 Rooms 15/ in Shop -.15.-

Although William Nicolson had purchased the property in 1779, his father, Robert, must have held title again in 1796 when he insured, "My Store 70 Buildings on Main Street at Williamsburg now occupied by myself." The buildings were described as "A, Wood Store two Story, 34 feet by 20 feet," and "B, Shop, wood house two Stories 27 feet by 20 feet." The store marked A was on Duke of Gloucester Street and "B" was in the yard to the north.5 The actual dimensions of the Nicholson Shop are 34'3" x 20'1-½". During an archaeological excavation in 1941-2, a foundation measuring 27'1-3/4" x 20'1-¾" was uncovered to the north of the surviving structure.6

Early nineteenth-century insurance records showed that the owners continued to use the buildings as stores and their sizes remained consistent. But by 1842, the property was advertised at public auction as consisting of, "…dwelling house, and store house attached, being well-arranged for the accommodation of two families, and therefore calculated to rent to great advantage."7 When Edward and Victoria Lee, the last owners of the house, purchased it in 1871, it was a two-story frame dwelling with a five-bay domestic facade and an ell on the northeast side. (See Illustration #1). According to Mrs. Lee, the appearance of her home had not changed between 1871 and the early 1930s when she was interviewed by Colonial Williamsburg.8

The Architectural Investigation

Because the Lees continued to reside in the house, first as owners, then as life tenants, architectural investigation was impossible and archaeological excavations were necessarily restricted to the surrounding lot during the first twenty years of the Williamsburg restoration. Limited archaeology was conducted on Mrs. Lee's property during the winter of 1941-42. Archaeologists uncovered the foundations of Dr. Pasteur's well-advertised apothecary shop on the western part of the lot as well as dependencies north of the Lee House which 72 may have been related to the Nicolson Shop. The foundation of the 27' x 20' building noted in the insurance policies was uncovered at this time.9