Excavations at the President's House College of William and Mary Archaeological Report Block 16 Building 2

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0075

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

EXCAVATIONS AT THE PRESIDENT'S HOUSE

COLLEGE OF WILLIAM AND MARY

1972

Introduction

The following observations may at first appear to provide a classic example of scholastic overkill, or, as it was put rather better by the Bard, "much ado about nothing". The study relates to a brick drainage system found in the basement of the President's House at the College of William and Mary during renovations , associated with the installation of central air conditioning. Neither the drains nor their contents do anything to change the history of the building, and although the discoveries pose numerous questions about themselves, very few are satisfactorily answered. If one asks, therefore, why so much time and effort has been devoted to these features, the answer must be the same as that so frequently voiced by mountaineers—"Because they are there". Once an archaeologist takes on a job, he has a responsibility to see it through to the end and to report anything of significance that he may find. At the same time, recognizing his own fallibility, it is beholden upon him to record every fact so that others may be able to read into them significance that he himself cannot detect. In the present instance, however, Colonial Williamsburg had a specific interest in the drainage system, for it was the first time that such drains had been seen in association with the kind of brick-arched tunnel leading away from the building that had been found elsewhere, but whose junction with the walls of the structures had 2 not before been found undisturbed. It was hoped, therefore, that it would be possible to determine how artifacts came to lie in the tunnels and to be carried down them for considerable distances, as was so graphically demonstrated in 1963 during excavations at the site of the John Custis House.

Historical Summary

The President's House at the College of William and Mary was built in 1732 and heavily damaged, if not destroyed, by fire in 1781 while being used as a hospital for French officers. With the aid of funds provided by the French government, the house was repaired in 1786 and has ever since continued to serve as the home of the President. It was restored along with the College's other eighteenth-century buildings by Colonial Williamsburg in 1931.

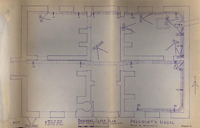

The 1972 Archaeological Evidence

In March 1972, Colonial Williamsburg undertook to provide the President's House with central air conditioning and to waterproof the basement, the latter a project calling for the removal of the existing brick floors, the laying of a concrete slab, and the partial replacement of the brick thereafter. Because the floors had not been taken up during the original restoration of this building in 1931, small test holes were dug through them in each room to provide the Department of Archaeology with some indication of their relationship to the subsoil beneath. Although most of the holes showed only that the brick floors were laid on sand, which, in turn, overlay natural mottled clay, the tests cut against the south wall of the southeast room showed that over the years, there had been considerable seepage from outside the building and this, coupled with the settlement of fill overlying an as yet 3 undetected drainage system, had caused the floors to sag along the wall lines (Plate I). Another cut against the east wall of the south "half" of the central passage (mechanical room) revealed a brick-lined drain which clearly had been installed in an attempt to cope with the problem of water seepage within the basement.l This drain was filled to the top with silt. The presence in it of small fragments of bone and flecks of shell mortar indicated that section of the channel had not been cleaned out when the building was restored. A drain of similar character ran the full length of the building interior from west to east, and this, like, the previously mentioned north-south section, was covered with flagstones which had evidently been taken up from time to time (Plates IIA & B). Nevertheless, this west-east drain was also filled with silt, though Mr. Neil Frank, who was in charge of the subsequent archaeological investigation, considered that it had been disturbed, if not explored, in the 1930's. The presence of the drains and the evidence of disturbed soil abutting against the east walls left no doubt that a careful archaeological investigation of the basement was needed before the concrete was laid. With that necessity established, the entire basement was swept out, and all the floors and seemingly pertinent architectural details were photographed.

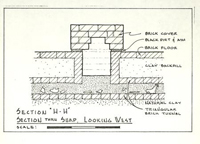

At the request of the archaeologists, the removal of the brick flooring commenced in the northwest room, a step that immediately revealed a brick drain running along the interior face of the north wall. The drain was of box construction with an interior channel 4 measuring 32" wide by 4" high, and it was overlaid by a thin spread of twentieth-century glass bottle fragments. Beside the drain, and resting on two bricks, was a small patch of compacted silt in which was found a fragment of Yorktown lead-glazed earthenware dating from the second quarter of the eighteenth century.l The sherds could well have been deposited at the time of the building's construction in 1732. At a point 11'4" from the northwest interior corner, the square brick drain changed to a triangular form—one that proved to run around the interior of the building from this point in the northwest room to within four feet of the southwest corner of the southeast room (Plate III). The resulting hook-shaped drain (in plan) had a fall of eleven inches carrying the water to a brickwalled sump abutting against the east wall of the northeast room. The previously encountered box drain running along the east-west axis of the building fed into the triangular drain against the east wall and so was of secondary date (Plate IV).

There was reason to suppose that the brick floors in the center passage had been relaid when the building was restored. So, too, had at least part of the floor in the northwest room (now identified as the laundry) for, as previously noted, over the drain and under the brick floor were found fragments of twentieth-century wine bottle glass. The southwest room (sitting room) floor had been patched repeatedly, and it was uncertain whether any original, undisturbed flooring remained. That in the southeast room appeared to have been laid in the late eighteenth or early nineteenth century using dark red bricks of smaller size than those used elsewhere.

5One of these bricks was scored with the figure 6000 (ante cocturam),l and it is suggested that the numerals identify the completion of a batch or order. Because the bricks in this room are of comparable size to those used in the dividing wall between the southeast and northeast rooms which had been rebuilt after the fire of 1781, it might seem likely that the wall construction and the laying of the floor are contemporary (Plate V). If this were the case, it would be reasonable to deduce that the west-east drain is of comparable date, but it will later be demonstrated that this was not so.

By far the most interesting, informative and, at the same time, enigmatic of the floors was that encountered in the northeast room where the brick pattern showed that the room had at one time been divided in two (at least in the flooring) along a north-south line at a point 10'10" from the east wall (Plate I). This basement room has two windows in the north wall, the most easterly of them exhibiting considerable repair along with considerable evidence of wear and damage at the jambs—in contrast to the matching window to the west that exhibits no such attrition. It might be argued, therefore, that as the joint in the floor patterns corresponds with the west jamb of the east window, the damage to the window opening related to an activity carried out in the easterly half of the room from which the western segment was protected by a party wall. There is, however, no indication of such a wall in the flanking masonry or in the ceiling joists, but it is entirely possible that the partition ceased to exist before the fire of 1781. This reasoning is based on the fact that there were traces of wood ashes 6 between the bricks along the line of pattern change, and also beneath the edge of what at first seemed to be a plinth-like brick block overlying the floor and abutting against the east wall. If these ashes were left from the fire, then the two forms of brick flooring must pre-date the 1781 damage to the building. The removal of the brick floor showed that both sections of brickwork were laid directly on clay and not on a sand bed, as was consistently the case elsewhere in the building. Pressed into the clay beneath the bricks in the easterly segment of the room were found two fragments of overglazed decorated Chinese porcelain of a type that could not be expected to date before the mid-eighteenth century.l It is clear, therefore, that this part of the flooring had been laid at a later date than the 1732 construction of the building. It might, therefore, be deduced that the brick flooring in the western half of the room was the older of the two.

It should be noted that a rectangular brickwalled sump had been cut into the clay below the eastern half of the floor (the sump measuring 2'10" wide by 3'4½" long), and that this had been repaired and filled with gravel at the time of the building's restoration in 1931 (Plate VI). The fact that this sump still draws water is evidence of its continuing efficiency. The top four courses are bonded with cement mortar, but it is uncertain whether the latter is contemporary with the construction of the entire brick-lined box.2

7The extent of the damage to the house resulting from the fire of November 23, 1781, is important to the interpretation and chronology of the basement. In spite of the fact that the Colonial Williamsburg Guidebook refers only to "accidental damage which Rochambeau at once ordered repaired at the expense of the French government",1 it is evident that Marcus Whiffen's more succinct and graphic assessment that the house was "gutted" was nearer to the mark.2 Only the total destruction of the building's interior would satisfactorily explain the fact that the central east-west wall had been rebuilt from floor level, increasing from 1'1" to 1'6" in thickness. It is important to note that this increased width resulted in the south edge of both sections of brick flooring in the northeast room being overlaid by the rebuilt wall, thus indicating that they pre-dated the 1781 fire (Plate V).

Following the measuring and photographing of the visible architectural features in the northeast room, the previously mentioned plinth-like brick feature abutting against the east 8 wall 3'1½" from the northeast corner was dismantled and found to have been built as a cover to an abandoned, brick-walled sump (Plates I and VI). That in turn led to a bricked-in drainage tunnel. The sides of the cover corbelled inwards creating an arched interior, a form of construction that would hardly have been employed if the structure had been designed as the base for a stove as had previously been deduced. At the outset it was hard to believe that such an unsightly and irregular "block" of masonry could have been an acceptable means of covering a sump which could easily have been packed tight, mortared over, and the existing brick floor extended across it.

Two important pieces of documentary evidence help to establish the later history of both the drainage system and the curious brick box. The first stems from the Colonial Williamsburg's architectural records which state that "the basement had been filled to approximately half its height by a former occupant of the house in an effort to exclude water from the basement."1 It is reasonable to deduce, therefore, that when the fill was inserted, the sump was still visible (though perhaps covered with a lid) and that because, in spite of considerable silting, it still served as a collecting point and a slow exit for seeping water, it was hoped that it would continue to do so. Thus, rather than filling it up, the cavity was bricked over in a rough and ready manner, the crudity of it being unimportant when the feature was to be buried under the new fill. When the dirt was removed by Colonial Williamsburg in 1931, 9 the enigmatic brick "plinth" was revealed, and being a supposedly "original" feature, it was carefully preserved. The fact that it concealed a sump and a bricked-up tunnel could only have been determined had the cover been dismantled.

It cannot be proven that the sump had previously been covered, but the fact that it contained nine inches of silt rich in wine bottle fragments dating no later than 1760, but no debris from the 1781 fire, strongly suggests it was normally covered and remained so after the house was rebuilt five years later (Figure 1). Shell mortar adhering to the wall above the drain arch also suggests a cover, perhaps in the form of a continuation of the tunnel arch into the basement.

The second significant documentary source is to be found in the William and Mary Faculty Minutes for March 14, 1831, wherein is discussed the need to drain ponds to the south and north of the

Section "H-H"

Section "H-H"

Section thru Sump, Looking West

10

College buildings. The Committee on Repairs reported that the north pond could be drained "by conducting the water into a subterranean passage which they have discovered in the rear of Mrs Daybrooks. This channel," the report went on, "which appears to be similar in structure to the main college sewer [,] leads from the cellar of the Prests house to the ravine in the rear of Jno Dipper's and was originally built for the purpose of discharging the water which collected there in large quantities. It is at present choaked up…" the committee added.1

It would appear from these minutes that both the sump and the tunnel mouth (though bricked-in) must still have been visible in the basement of the President's House in 1831; otherwise, it is unlikely that anyone would have known that the tunnel still reached to the cellar. Thus, the brick cover must have been installed at some later date—along with the dirt fill. Unfortunately, there is no record of any artifacts being retrieved from the fill, and consequently no archaeological dating can be added.

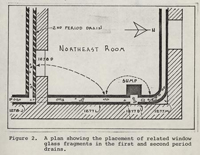

Artifactual dating for the silting of the sump, on the other hand, was sufficient to leave little doubt that the eight-inch accumulation within it had not been cleaned out since the third quarter of the eighteenth century.2 The glass fragments included large pieces from wine bottles as well as pieces of crown window glass that had been cut into small rectangular panes. Both window glass and wine bottle glass extended to the north and south into triangular brick-lined channels that fed into the sump, the 11 artifacts extending north and west for a distance of seven feet and southward into the southeast room.1 Most of the pieces were lying close to, if not resting on, the brick floor of the drains that were clogged to their roofs with silt. One entire bottle neck and part of its shoulder took up most of the space within the north channel, and no entirely adequate explanation has been forthcoming for its presence there (Plate VII). Crossmends between the window glass fragments reveal that the silting of the square-section west-east drain in the southeast room occurred contemporaneously with the silting of the triangular south-to-north drain against the east wall and into which it fed. This would suggest that at least some of the window glass entered the system from the west-east drain and not from the sump as had at first been supposed (See Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

A plan showing the placement of related window glass fragments in the first and second period drains.

The brick-lined channels were set in a 1'8" trench running round the inside of the building, abutting against the north, east, and south walls and extending to a maximum depth of 1'5½" below its bottom course. Colonial Williamsburg's Director of Architectural Research, Paul Buchanan, does not think it likely that the original builders would have risked weakening the foundations by digging such a trench; in which case the drains, the sump, and the tunnel must have been installed at some time after 1732, presumably when the first water seepage problems were detected. Although the placement of a trench against the walls may have been, unacceptable architectural practice, there is reason to believe that the actual drains were laid with some precision and under the direction of a skilled craftsman. While the drain arm extending south and west does not reach nearly as far along the south wall as does its northerly counterpart (See plan, Figure 5), both channels are forty-three feet in length and have a fall of a quarter-inch per foot, suggesting that the bricklayers were working to a prescribed formula. The north arm reached into the northwest room and there joined to an extension (see p. 3) of square construction. It is reasonable to deduce that the additional 9'6" was added contemporaneously with the similarly constructed central west-east drain, presumably at some date in the period 1760-1781.

The previously noted crossmends between window glass fragments lying both on the silted floor of the central west-east channel, and in the triangular drain immediately south of the sump, leaves no doubt that both drains were in existence prior to the 1781 fire and perhaps much earlier. It would seem, therefore, that the system was heavily silted by the time the building burned, but in 13 spite of that, the flagged drain covering in the south room was retained when its brick floor was replaced (if, indeed, it was) at the time that the interior walls were rebuilt in 17861 (Plate IIA)

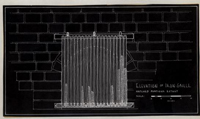

As previously noted, the brick-lined sump contained approximately nine inches of silt, and it is deduced that it had lain or slowly accumulated there undisturbed for a considerable period of time, probably because the opening was closed by a lid or because the silt was normally covered by at least a film of water. When first built, the sump represented an in-cellar terminal to the arched brick tunnel (which in 1831 would be converted into a drain, for the north pond) that passed through the basement wall and curved away in a northeasterly direction towards what is now Richmond Road. The junction of sump and tunnel had at first been parted by an iron grill, the vertical bars only a quarter of an inch apart, presumably to prevent vermin, larger animals, or human intruders from entering the cellar via the tunnel exit in "the ravine in the rear of Jno Dipper's" (Plate VIII). At some date, almost certainly in the eighteenth century, the tunnel was abandoned after it had silted to the level of the spring line of the roof. The iron grill was then breached by wrenching or beating the bars out, a job that was accomplished in a very sloppy manner. The base plate or bar (1-¼" x ¼") was left in situ as it was mortared between the walls of sump and tunnel, as also were three of the bars which were thus conveniently protected and so survived 14 to provide an accurate picture of the grill's original appearance (Figure 3). Others of the bars had snapped off three and four inches from the base plate's rivets, and they remained protruding this way and that like an orthodontist's nightmare. When first installed, the bars had been set approximately a quarter-inch apart, each bar being square in section (½" x ½") and set diamond-ways to the cellar. None survived to its full height, but two iron staples in the wall above the tunnel mouth had almost certainly held the top plate in position, in which case the grill would have had a maximum height of 1'9".

Figure 3.

Figure 3.

An elevation showing the reconstructed iron grille

in situ after removal of the brick sump.

The jagged opening left after the removal of most of the grill was roughly sealed with bricks from within the cellar, seemingly laid without mortar, for none survived between them-though water seepage might have washed it out.1 The closing wall made use of both complete bricks and brickbats, and although reasonably neat on its exposed face, the tunnel side varied from approximately four inches to eight inches in thickness, depending on whether the bricks were laid as headers or stretchers, and was supported by the silt fill. The bottom course did not fit snugly to the floor and it is likely that rain water was able to pass beneath the brickwork, both into the sump from the tunnel and out of it from seepage in the cellar.

Unlike the tunnel found at the Custis House which had been built so that it abutted against the exterior of the cellar wall, the President's House tunnel passed right through the wall, the ends of the arch bricks terminating at the interior face of the cellar's east wall. The sides continued to a distance of three courses below the bottom of the wall and ended at the same elevation as the drain floor. The curvature of the tunnel's roof interfered with the regularity of the basement's English bond, but as there was no visible difference between the mortar in the bonding associated with the arch and that of the regular courses to the north and south of it, it could be argued that the tunnel was laid at the same time that the wall was erected around it. Alternatively, it could (as Mr. Buchanan has suggested) have been cut through the wall at a later date. In support of the first proposition, it is worth noting that the opening's placement close to a corner of the 16 basement (4'5½" from the NE corner) is paralleled by the locations of the drainage tunnels at the Custis House in Williamsburg and at "Corotoman" in Lancaster County, l both of which are thought to have been installed when the houses were first built.

The Window Glass

Like the drainage system, the artifacts from this excavation pose as many questions as they answer. Most disturbing of them is the question: Whence came the broken panes that were found in the sump and in the adjacent drains to the north, south, and west?1 There were fragments from at least seven panes, all of them of greenish-blue crown glass, all rectangular and measuring approximately 6" x 3-5/16", and most of the edge pieces showing evidence of having been mounted in lead.2 To support that interpretation, the drains south and north of the sump yielded four short lengths of turned lead whose H-sections were of a size that matched the widths of the scars on the edges of the panes.3 It is reasonable 17 to suppose that both the lead and the glass came from the same window, and as it is unlikely that leaded glass would have been used in furniture glazing (e.g., bookcase doors), the only other explanation is that the fragments are architectural in origin. If so, where were they used?

Mr. Buchanan does not think it at all likely that any windows of the President's House would have been fitted with casement (rather than double-hung sash) windows. It should not be inferred, however, that casement or fixed leaded windows had ceased to be used in Williamsburg by 1732. On the contrary, they , continued considerably later.l But if such glazing was not employed at the President's House, one is left asking: What were the fragments doing in the basement? It is virtually the same question that architectural historians have long been asking about Robert Carter's "Corotoman" which burned in 1729 and in whose cellar was found a complete iron frame from a casement window. 2 As Carter's house is believed to have been one of the most costly and modern of its day, the use of such old-fashioned windows would have been totally out of character--which is the same argument that Mr. Buchanan voices apropos of the President's House. In the absence of documentary evidence describing or illustrating the 1732 windows, one's only course is to bring in the old Scottish verdict of "not proven".

Conclusions

The President's House was completed in 1732, and the thin surviving evidence points to the construction of a brick-lined drainage system either contemporaneously with or shortly after the building of the dwelling. The drains were extended and added to, perhaps within a few years of their original construction. Subsequent heavy silting in the tunnel leading from the basement to the ravine caused the system to be abandoned and the tunnel's entrance into the house to be bricked up, a change that probably occurred prior to the Revolution. Thereafter, the sump and drains, inside the building continued to carry off seeping rain water, but the blocking of the tunnel slowed the flow and encouraged a gradual silting which finally blocked the channels. Nevertheless, the sump continued to exist after the house burned and was rebuilt, and remained open until at least 1831 when the disused exterior tunnel was converted to a new purpose. The cellars were subsequently partially filled with dirt in an effort to control "the water which collected there in large quantities"1 at which time the sump continued to be honored, being carefully bricked over so that water seeping below the brick floors could still drain into it. The nineteenth-century brick cover was exposed in 1931 when the fill was removed and the house restored. This brick cover, the sump itself, and large sections of the colonial drain channels were dismantled by the archaeologists in 1972, prior to the installation of new drains around the interior of the building. At the same time, all the colonial and later brick floors were taken up so that a concrete bed could be laid as part of the latest attempt to waterproof the basement.

Footnotes

William and Mary College Quarterly, 2nd Series, VOl.VIII, p.246, Report of the Committee on Revolutionary Claims, Thirty-first Congress, Second Session, Senate Report No. 219. "Whilst those buildings were thus occupied by [the French troops] the President's house and a portion of the [College] building were destroyed by fire…"

"Madison Papers", Vol.XIII, p.59, f.15, 505; Rev. James Madison to James Madison, Jr., Williamsburg, June 15, 1782. "I have not a book left since the conflagration of the house in which I lived…"

William and Mary College Papers, Folder 105-B; letter from Rev. James Madison to Professor Samuel Henley, Williamsburg, August 6, 1783. "I then ordered [the boxes of books] to be carried over to the President's house, in which I lived. But that house, with everything it contained, was consumed by fire."

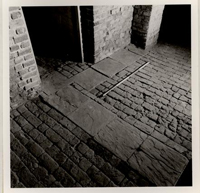

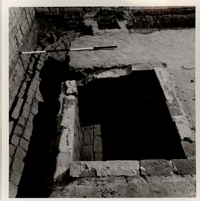

Plate I.

Plate I.

Floor of northeast room prior to the removal of brick paving showing, at left, the settlement overlying the drainage system trench and, in the middle distance, the brick-lined and gravel-filled sump that appears to have been added in the nineteenth century. Beyond this is the brick box covering the small eighteenth-century sump. Settlement over the drain trench is also visible to the right of the box and extending to the southeast corner of the room. Also of significance is the change of brick pattern across the middle of the room from north to south. Photo from the northwest. Negative No: 72 FD 345.

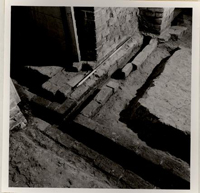

Plate IIA.

Plate IIA.

Brick flooring in the basement north-south passage with door to southeast room at top left, and showing stone flagging overlying secondary brick drain. Photo from the northwest. Negative No. 72 FD 357.

Plate IIB.

Plate IIB.

As IIA after the removal of brick and stone flooring to reveal the secondary brick-lined drains. Photo from the northwest. Negative No. 72 FD 381.

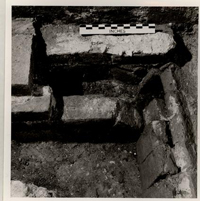

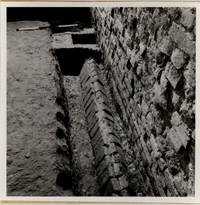

Plate III.

Plate III.

North wall of the northwest room showing the west end of the triangular drain and the square-sectioned secondary drain abutting against it. Photo from the west. Negative No. 72 FD 380.

Plate IV.

Plate IV.

Junction of the square-sectioned east-west central drain and the earlier triangular drain along the east wall of the basement. Photo from the south. Negative No. 72 FD 403.

Plate V.

Plate V.

Doorway between the northeast and southeast rooms showing the 13-inch wall overlaid by an 18-inch wall believed to have been constructed in 1786. Note that the brick paving in the northeast room passes beneath the edge of the later wall and therefore pre-dates it. Photo from the north. Negative No. 72 FD 356.

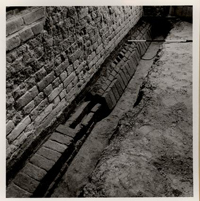

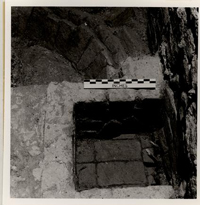

Plate VI.

Plate VI.

The northeast corner of the northeast room after the removal of brick paving, the emptying of the nineteenth-century sump, and the exposure of the eighteenth-century triangular drain and its associated sump. Note sealing of the tunnel leading out from the sump. Photo from the west. Negative No. 72 FD 378.

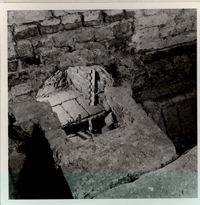

Plate VII.

Plate VII.

The eighteenth-century sump showing the north triangular drain emerging into it and, at right, the remains of the iron grill that was dismantled when the tunnel exit was filled. Photo from the south. Negative No. 72 FD 364.

Plate VIII.

Plate VIII.

The eighteenth-century sump after the removal of the brick infilling of the tunnel. Photo from the west. Negative No. 72 FD 435.

Plate IX.

Plate IX.

The triangular drain immediately south of the brick sump. The dismantling of this drain yielded many of the window glass fragments. Note the elevation of the top of the drain below the bottom course of the east wall of the northeast room. Photo from the south. Negative No. 72 FD 365.

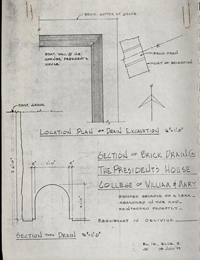

Section of Brick Drain at the President's House, College of William & Mary

Section of Brick Drain at the President's House, College of William & Mary