The Economic Role of Williamsburg

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 0066

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

Notice To Readers

The Economic Role of Williamsburg by James H. Soltow was published in 1965 by Colonial Williamsburg, Incorporated, and distributed by the University Press of Virginia as part of the Williamsburg Research Studies series. The following is the original manuscript from which the published version was produced.

THE ECONOMIC ROLE OF WILLIAMSBURG

TABLE OF CONTENTS

| PREFACE | i |

| TABLE OF CONTENTS | iii |

| LIST OF TABLES | iv |

| I THE WILLIAMSBURG MEETINGS | 1 |

| II MARKETING AGRICULTURAL STAPLES FOR EXPORT | 19 |

| The Tobacco Trade | 20 |

| Major Markets | 24 |

| Channels of Trade: The Consignment System | 27 |

| Channels of Trade: The Direct Purchase of Tobacco | 33 |

| Market Policies | 47 |

| The Produce Trade | 57 |

| Major Markets | 60 |

| Purchasing of Agricultural Produce | 68 |

| Summary | 73 |

| III MONEY, CREDIT, AND FOREIGN EXCHANGE | 75 |

| The Currency Problem | 76 |

| Currency in Circulation | 76 |

| Commodity Money | 79 |

| Paper Money | 81 |

| Substitutes for Money | 87 |

| The Credit System | 91 |

| The Terms of Credit | 91 |

| Payments on Debt | 101 |

| Sterling Exchange | 109 |

| The Bill of Exchange | 115 |

| Organization of the Exchange Market | 115 |

| Summary | 130 |

| IV WILLIAMSBURG AND NORFOLK IN THE VIRGINIA ECONOMY | 132 |

| The Growth of Norfolk as a Metropolitan Center | 141 |

| Conclusion | 147 |

| BIBLIOGRAPHY | 149 |

| TABLE I: Exports from the Seven Districts of Virginia, January 5, 1772-January 5, 1773 | 19 |

| TABLE II: Estimated Value of the Principal Export Commodities of Virginia and Maryland | 19 |

| TABLE III: A Recapitulation of the Quantity of Tobacco Exported from Virginia, Specified Years, 1619-1758 | 19 |

| TABLE IV: Imports of Tobacco, England and Scotland, 1761-1775 | 19 |

| TABLE V: Number of Hogsheads of Tobacco Exported From Virginia, 1745-1756, 1768-1769, 1772-1773 | 19 |

| TABLE VI: Tobacco Imports, Scotland, Specified Years, 1708-1771 | 25 |

| TABLE VII: Tobacco Exports, Upper District of James River, October 25, 1765-0ctober 25, 1766 | 25 |

| TABLE VIII: Tobacco Exports, England 1773 and Scotland, 1773 | 26 |

| TABLE IX: Estimate of Number of Hogsheads of Tobacco to be Collected at Virginia Stores of William Cuninghame & Company, October, 1772-October, 1773 | 47 |

| Table X: Proposed Plan of Shipping of Tobacco of William Cuninghame & Company, October, 1772-October, 1773 | 47 |

| Table XI: List of Glasgow Firms & Importations of Tobacco, 1774 | 47 |

| Table XII: Official Value of Foreign Coins in Circulation in Virginia in the Eighteenth Century | 78 |

| Table XIII: Official Values of Currency in the Colonies in the Eighteenth Century | 79 |

| Table XIV: Virginia Bills of Credit, 1755-1773 | 83 |

| Table XV: Amount of Cash on Hand and Accounts Receivable at the End of the Accounting Year, William Prentis & Company, Williamsburg, 1734-1775 | 94 |

| TABLE XVI: Average Annual Exchange Rates, Virginia Currency on Sterling, 1740-1775 | 116 |

| TABLE XVII: The Course of Exchange, 1764-1773 | 116 |

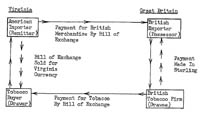

| Figure I A Typical Exchange Transaction Between Virginia and Great Britain | 111 |

PREFACE

The importance of Public Times in Williamsburg is not unknown to those familiar with the life of this eighteenth-century community. People from all parts of Virginia came to the capital four times each year to transact their business as well as to carry on the machinery of government and to participate in the gala social affairs which took place at these times. The purpose of this report is to describe and analyze the role which Williamsburg, through the periodic Meetings of Merchants, played in the economy of Virginia. In other words, the basic questions are: What did businessmen do when they came to Williamsburg, and what significance did their periodic assembling in the capital have in relation to the economic life of the province?

Any study of the economic history of eighteenth-century Virginia touches inevitably upon the relations between merchant and planter and upon the conflict between the business and agrarian ways of life. If any partiality is shown here towards the business point of view, it results in part from the fact that merchants' records were the major sources for the study. However, the emphasis herein is upon the Williamsburg Meeting of Merchants as an institution which developed to meet the needs of business in a decentralized agricultural economy. As long as Virginians produced goods for exchange (as opposed to production for the exclusive use of the producer), some kind of a system of business was necessary to provide the mechanism for exchange.

A word might be said here about the facilities provided to make this study. The original sources which I used are located in widely-scattered depositories from Edinburgh to San Marino, California. However, all of these manuscripts have been made available in Williamsburg v. as a result of the microfilming program of Colonial Williamsburg's Research Department. Unquestionably, this has resulted in a great gain in efficient use of time as well as in convenience.

Finally, I wish to express my appreciation for the cooperation and encouragement extended by Dr. Edward M. Riley, Director of Research, Dr. Richard P. McCormick, special consultant to Colonial Williamsburg, and my colleagues in the Research Department. Thanks also to those who have made available materials at various stages of my research.

August 24, 1956.

THE WILLIAMSBURG MEETINGS

The political role of Williamsburg has been defined rather clearly. In Williamsburg were the institutions of colonial government — the Governor or Lieutenant-Governor as representative of royal authority in Virginia and the Council and Burgesses as representatives of the colony's property owners, as well as the General Court, the highest unit in the province's judicial system. As Carl Bridenbaugh has suggested, the important political lesson of the Williamsburg experience is the story of how a republican form of self-government was developed by an essentially feudal governing class.1

Less definite is the role which Williamsburg played in the economic life of Virginia. Neither contemporary observers nor writers of this century have been able to reach agreement on the significance of the community to the colony's economy. A French traveller in 1765 implied that the town was second in importance in Virginia trade only to Norfolk,2 while St. George Tucker asserted in 1795 that "there never was mch trade in Williamsburg."3 Lyon G. Tyler wrote in 1907 that "the city was the center of the business interests of the colony."4 but Robert W. Coakley concluded in 1949 that Williamsburg's "importance was political not economic."5

2.The economic role of Williamsburg was indeed different from that of the larger urban centers, such as Philadelphia, New York, Boston, and Charleston. Each of these centers was the nucleus of a metropolitan economy, in which the wants and needs of the population of the area were "supplied by a system of exchange concentrated in a large city" which was "the focus of local trade and the center through which normal economic relations with the outside" were maintained.6 Each of these cities was a port for the ocean-going ships engaged in foreign trade; through each were funneled the imports and exports of a hinterland trading area; in each was a business community which collected commodities for export and distributed imported goods.7

Geography, however, was the principal force hindering the growth of a similar metropolitan center to dominate the economic life of Virginia. The presence of the four great tributaries of the Chesapeake, accessible for long distances to most ocean-going vessels, rendered unnecessary the development of a single entrepot to handle the imports and exports of the colony. The James River was navigable by the largest ships of the eighteenth century for a distance of one hundred miles, the York-Mattaponi-Pamunkey for sixty, the Rappahannock for seventy, and the Potomac for 110. Smaller vessels usually could 3. proceed some miles farther to the falls of each river. In addition, there were numerous tributaries, particularly of the James and Potomac, which provided navigation for local craft.8

Jefferson's assertion in 1782 that Virginia had "no ports but our rivers and creeks"9 was more applicable to the situation fifty to seventy-five years previous than to that of his day. The determined efforts of the Virginia government from an early date to foster urban development were thwarted by the Tidewater planters' practice of shipping tobacco and receiving goods at their own landings, which continued through the seventeenth and into the first quarter of the eighteenth century.10

Two developments in the second quarter of the century, though, stimulated an urban growth in Virginia. One was the Tobacco Inspection Act of 1730, which led to the rise of a numerous group of small river towns. Under the terms of this law, planters were no longer permitted to ship tobacco directly from their own wharves but were required to take their hogsheads to public warehouses for inspection and storage prior to shipment. Around these warehouses in the Tidewater area developed communities such as Cabin Point on the James, Urbanna on the Rappahannock, as Dumfries on the Potomac, as businessmen capitalized on the opportunity of trading with the planters when the latter carried their tobacco to the warehouses. Secondly, population expansion into 4. the Piedmont, above the head of navigation, resulted in the need for trans-shipment of goods and produce at the falls of each of the rivers. Warehouses and stores provided the nuclei for the falls towns, such as Richmond on the James, Petersburg on the Appomattox, Fredericksburg and Falmouth on the Rappahannock, and Alexandria on the Potomac.11

Special circumstances contributed to the growth of Norfolk to the position of Virginia's largest city and leading business center by 1775. The growing West Indian commerce, plus a local trade in tobacco and other agricultural products, lumber, and naval stores, provided the basis for the town's economic rise. By the end of the colonial period, Norfolk, located in a strategic position at the entrance to the Chesapeake, held promise of developing into a metropolitan center for the entire Bay area, Norfolk entrepreneurs conducted trade on a large scale and controlled diverse types of enterprises such as distilling and land speculation.12

Geography thus imposed a pattern of commercial dispersion, with only Norfolk possessing more than local trade interests. Since ocean ships could reach all parts of the colony to the fall line, many small centers performed most of the business of their localities.

Although Virginia's economy was decentralized, with each area of the dominion holding direct lines of communication with Britain, 5. Williamsburg provided a focus for the economic as well as the political life of the colony. Williamsburg did not have port facilities, except those for local craft at College and Capitol Landings,13 and its businessmen were concerned largely in the retail and service trades. However, the larger aspect of Williamsburg's economic life centered on the business carried on during Public Times. Four times each year, businessmen from all parts of the colony met at Williamsburg — at the sessions of the General Court in April and October and of the Oyer and Terminer Courts in June and December. Although there was not even an official meeting place, much of the business of the colony was initiated and settled in Williamsburg. Merchants conducted their affairs in the boarding houses, in the taverns, and on the streets. One traveller reported that in the Raleigh Tavern "more business has been transacted than on the Exchange of London or Amsterdam."14 Back of the Capitol was an extension of the Duke of Gloucester street, known as the "Exchange," where financial transactions were made.15

Williamsburg was truly a bustling metropolis during Public Times, when a normal population of about 1,500 expanded to 5,000 or 6,000 people. Lodgings could be obtained only with difficulty. The tavern next to the Exchange, operated by Mrs. Vobe and later by Christiana Campbell, was a favorite because of its location and its 6. reputation as the place "where all the best people resorted."16 However, there were other lodgings, equally desirable, in the area near the Capitol. Mrs. Mary Davis, for example, leased a large brick house a block west of the Capitol, and advertised "12 or 14 very good lodging rooms with fire places in most of them, which will hold two or three beds in each."17 Factors of one of the largest Scottish tobacco firms engaged lodgings here in 1770 and considered renting behind the tavern as a Public Times.18

Not only merchants but also planters were present in Williamsburg during Public Times. Robert Carter of Nomini Hall, for example, made special reference to the fact that he would be unable to be "at Williamsburg this next meeting of the Merchants and Other Gentlemen there."19 As Governor Fauquier pointed out, "persons engaged in Business of any kind constantly attend" the Meetings.

Thomas Nelson called the Meetings of the Merchants "a very busy time."21 A foreign traveller was amazed by the town during Public Times: 7. "In the Day time people hurying back and forwards from the Capitol to the taverns, and at night, Carousing and Drinking."22 There were many diversions for the merchant or planter who spent much of the rest of the year in a relatively isolated location, as he took advantage of the opportunity to witness horse races, cock fights, and theatre performances.23

People travelled to Williamsburg by water and by land. Those from Norfolk had the choice of two weekly packets to Burwell's Ferry near Williamsburg. One boat left Norfolk on Wednesdays and returned on Saturdays, the other sailed on Thursdays and Sundays. Passage cost five shillings, for which "the best accommodations for passengers" were promised.24 Those from the south side of the James rode to Hog Island, where they could stable their horses, and used the ferry across the river.25

Since no formal commercial institutions developed out of the business activity of Public Times in Williamsburg, there is little existing information to indicate precisely how the Meetings of Merchants functioned. Businessmen evidently accepted the Meetings as part of the routine of trade and thought it unnecessary to explain to correspondents exactly what they did at Williamsburg, other than to refer to a specific transaction or item of business. Only when an unusual occurrence took place at a Meeting did a letter-writer see fit to comment at any length 8. on his activities in Williamsburg.

Indeed, there was no formal organization of the Meetings of Merchants before 1769. The rules drawn up in June of that year, though, likely reflect long-established customs and procedures of business. In the Raleigh Tavern, "a meeting of all persons concerned in the exchange and commerce of this country" agreed "to expedite the mode and shorten the expense of doing business" by adoption of the following set of rules:

First. That the 25th days of October and April, and the 1st days of the Oyer courts, shall be the fixed days of meeting in Williamsburg for all persons concerned in the exchange and commerce of this country.

Second. That the time limited for settling the price and course of exchange, and the payment of all money contracts in the General Courts, shall be three days; to begin from the said 25th days of October and April exclusive of Sundays, and in the Oyer courts from the first days of the said courts to the first Friday in the said courts.

Third. That all persons who shall engage for the payment of money, or other contracts, in Williamsburg, in the General and Oyer courts, shall be deemed violators of their engagements, and declared absentees, if not present on the above first days.26

At the Meeting of June, 1770, a Committee of Trade, with 125 members, was organized under the chairmanship of Andrew Sproule, wealthy Norfolk merchant, "to take under the consideration the general state of the trade in this colony." The message issued by the first session of the committee, "To the Merchants and Traders in Virginia," outlined the over-all purpose of the organization:

It has long been a matter of surprise, and concern, to many hearty friends to the trading interest of this colony, that a body of men, respectable as well from their number as the nature and extent of their connexions, should never yet (in imitation of Great Britain, and other trading countries) have formed themselves into a society, upon regular and liberal principles; 9 by which means they would have had frequent opportunities of establishing a confidence with each other, exceeding to their interest as individuals, and of gaining that dignity in the community to which they are so justly entitled.27The Committee, organized in part to formulate the merchants' policy in the growing controversy between the American colonies and the British government, was similar to the associations formed at about the same time in the other colonies. New York merchants founded a Chamber of Commerce in 1768, followed by those of Charleston, South Carolina, in 1773.28

In the spring of 1771, 168 "principal Merchants" of Virginia subscribed "to an Agreement to meet punctually, for the future," during the General Court sessions in April and October, "and that they expect all those who have any Business with them will meet regularly on these Days."29

Again, in November, 1772, it was "unanimously agreed" by the merchants, assembled in Williamsburg, "to engage to meet, and give our attendance in this city, either in person or by our representatives, in the 25th days of January, April, July, and October." A committee, composed of "a select Number of" the body of merchants and chairmaned again by Sprowle, received power to discipline traders who did not attend the Meetings regularly. If the committee judged the reasons 10 for non-attendance to be unsatisfactory, it was empowered to levy a fine of £5 "which is to be applied to charitable purposes." Names of those who refused to pay fines were to be published, "as Persons who do not pay a proper Regard to their solemn Promises and Agreements." Merchants from all parts of the colony were represented on the committee of twenty-eight members, any twelve of whom constituted a quorum to take action.30

For reasons which will be considered more fully at a later point, even the system of fines and threat of public notice of violators of the rules failed to bring all members of the Virginia business community to Williamsburg at the appointed time of some of the Meetings during the 1770's. In June, 1774, seventy-two merchants found it necessary to state that they had "resolved and are determined, for the future, to meet" in Williamsburg "every 25th day of October and April; of which we give this publick Notice, that those who have Business to transact with us may know when to attend."31

No specific explanation can be given of the origins of the Meetings of Merchants. However, it seems likely that merchants who had legal business, such as suits for collection of debts, made a regular practice of attending the sessions of the General Court in Williamsburg from an early date. Since merchants and planters from all parts of the colony were in Williamsburg together for court sessions, they could use 11 this opportunity to settle accounts, make payments, and buy and sell bills of exchange on Great Britain.

Philip Lightfoot, a Yorktown merchant, described attending the James City County Court twice in 1735 "to receive a Smal[l] bill" for a sum owed him by a New Kent County planter.32 Francis Jerdone referred in 1741 to the market for bills of exchange at Williamsburg: "Bills at present are So plenty & Cash So Scarce."33 In 1749, Jerdone reported that "the Exchange during the last Generall Court got up to 22 ½ for good bills, as there was a greater plenty of Cash in Williamsburg for that purpose than has been for many years past."34 According to Jerdone's letterbook covering the period from 1756-1763, he travelled to Williamsburg in October, 1756, in April, October, and December, 1757, in April and October, 1758, in April, June, October, and December, 1759, in April and October, 1760, 1761, and 1762.35

Very often, comparison of institutions and practices with those in different places and at different times gives greater perspective and meaning. For example, Professor Baxter, in his detailed study of the business careers of the Hancocks, has noted several striking similarities between the methods used by eighteenth-century Boston merchants and those employed by traders of an earlier period in Europe. Particularly in their use of triangular settlements of balances, the 12 Hancocks followed a practice similar to that of European businessmen in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. In both cases, a similar reason, the scarcity of money accounted for the practice which was followed.36

Using this kind of approach to our problem, we can see that the Williamsburg Meetings of Merchants resembled in many ways the great fairs of the Middle Ages. Certainly, the Meeting was like the fair in that it was "a periodic meeting-place for a distant clientele and attendance at it did not depend on the density of the local population."37 Because geography hindered the development of a metropolis to centralize trade in Virginia, it was not unusual that business developed some institution to meet its needs, in the way that the medieval fair grew as a facility for trading before the development of the urban exchange.38

At the Meeting, many types of business could be transacted. Although there appears to have been little display and sale of manufactured goods, a major characteristic of the medieval fair, occasional references appear to indicate that some Virginia merchants placed orders for European goods during the Meetings. For example, a Richmond store wrote to a Glasgow firm in 1757 that "we have Received, all the goods we Bought and ordered at the gen[era]l court."39 In 1773, a Norfolk merchant advertised "a large Parcel of KENDALL COTTONS," which had been 13 consigned to him by the English manufacturer. "Any Person inclinable to purchase," the advertiser continued, "will please to apply to him at the ensuing Meeting in Williamsburg."40 A year earlier, a Cabin Point storekeeper advised that those interested in purchasing "the Remains of a Store" could see the invoice and inventory of goods at the next Meeting.41

Merchants who exported Virginia iron products could rely upon placing orders at Williamsburg. A trader located near Richmond pointed out to a Philadelphia correspondent in 1773 that "the Merch[an]ts. … commonly engage the several quantities [of iron) they may want from the Iron Masters who attend there."42 Evidently auction sales of imported commodities were fairly frequent during Public Times. For example, Charles Steuart in 1759 sent part of a shipment of powdered sugar from New York "to W[illiam]sb[ur]g last court in dec[embe]r. to be sold at public sale."43

Although Williamsburg was not a seaport, shippers usually could secure cargo space to most major European ports during Public Times. Ship owners or captains often attended the Meetings to meet merchants for the "Opportunity to commune on Terms of Freight."44 Those with vessels to let on charter also advertised their presence 14 "during the General Court" in Williamsburg to deal with shippers.45 Most Virginia shippers placed their marine insurance directly with underwriters in Britain or in Philadelphia. In 1771, though, a Norfolk businessman opened an "Ensurance Office" where small shippers could order the required insurance; "those who attend the Courts may pay the Premiums" in Williamsburg.46

In a time of slow and uncertain communication, even within the colony, the Meeting provided an opportunity for merchants from different parts of Virginia to confer regarding prospective joint ventures. Most businessmen recognized the danger of risking a substantial amount of their capital in a highly speculative venture such as the slave trade. In the absence of a formal device to spread risks, such as the corporation, merchants worked out agreements for joint capitalization of single ventures of speculative nature.47 "In Consequence of the Conversation we had with you here," began one contract drawn up by Neil Jamieson and five other merchants in Williamsburg in May, 1770, "we hereby agree with you to be each of us concerned in the purchase of a Cargo of Negros to be made in the 15 made in the West Indies."48

More important and fundamental, though, was the growth of the Meeting as a "money market" for Virginia. In the way that a major function of the medieval fair was the clearing of debts contracted at preceding fairs,49 so the Williamsburg Meeting was the occasion for the settlement of credit terms for a wide variety of transactions ranging from the purchase of export commodities to the transfer of title to real estate. It was easier to make personal transfers of payment than to ship money or other means of settlement from one part of the colony to another. Then, too, the man who made a purchase often had to collect a sum due to him before he could make final payment. Also, government offices were available to record transfers of property where necessary, and the court system was at hand to begin proceedings against recalcitrant debtors.

Thus, most terms of payment provided for settlement during Public Times. For example, Robert Carter advised a Dumfries merchant that "whatever Corn or Wheat you Purchase [in the Potomac area] in 16 Consequence of this Order I will pay for att the Assembling of the Merchants att W[illiam]sburg."50 An advertisement of a cargo of slaves stated that "Merchants Notes, payable at the General Courts in Williamsburg, will be received in Payment."51 "One Half of the Purchase Money" of a tract of land in Hanover County, according to another notice, was "to be paid at the next Meeting of the Merchants."52 Notices appeared regularly in the press urging debtors "to make Payment before or at the Meeting of the Merchants."53 Creditors advised that they would be present at the Meetings with lists of debts due.54

As suggested by the rules developed in 1769, one of the most important tasks of the Meeting was to determine, through bids and offers, the rate of sterling exchange, or the value of local currency in terms of British sterling. The rate varied considerably, affected by many factors such as the price level and the volume of imports and exports. Sterling bills of exchange, derived from sales of agricultural products abroad, represented the bulk of the colony's negotiable wealth and were used to pay for the imports of manufactured goods. The Meetings in Williamsburg apparently provided the only active market in Virginia for sterling exchange. Charles Steuart, for example, pointed out from Portsmouth in 1761 that "we seldom can purchase any [bills of exchange] 17 between ye. co[ur]ts."55

Williamsburg, unlike Philadelphia, Boston, and other metropolitan centers of the eighteenth century, was not an assembly and trans-shipment point for the export commodities of the colony. However, as one writer on the Virginia tobacco trade has pointed out, "the one central market was in Williamsburg during the Meetings of Merchants."56 Although the ultimate market for tobacco and other agricultural commodities lay in Europe, the periodic assembling of most of the merchants of Virginia provided an exchange of information regarding colony-wide crop prospects as well as the latest information about prices in Britain and other markets. Traders were able to secure current price quotations on which to make decisions regarding purchases. The Williamsburg Meeting lacked the formal organization of a modern commodity exchange as well as some of its special functions, such as a futures market, but it did seem to fulfill a major objective of an exchange, "to make buying and selling open and competitive."57

To summarize, we might characterize the Meeting of Merchants as an institution developed to meet the need of business for some kind of central system of exchange in a decentralized economy, It contained some elements of a modern exchange as well as many of the characteristics of an older economic institution, the medieval fair. Outlined in the 18 pages following is a fuller analysis of the role of the Williamsburg Meeting in two of its major functions: as a "commodity market" for agricultural exports, which provided the basis of Virginia's wealth, and as a "money market" to mobilize the colony's financial resources.

MARKETING AGRICULTURAL STAPLES FOR EXPORT

The economic life of Virginia, like that of the other English colonies in America in the eighteenth century, was based upon agriculture. The surplus products of the plantations and farms were exported to pay for the needed imports of manufactured goods and commodities not produced in Virginia. Table I shows the quantities of the colony's exports to each of the major market areas for 1772. The purpose of this chapter is to outline briefly the methods by which Virginia's commodities arrived at foreign markets.

THE TOBACCO TRADE

Tobacco was the basis of Virginia's economy through the Colonial Period. Despite the growing importance of other economic activities, the tobacco trade still accounted for over three-fourths of the value of exports of Virginia and Maryland in the early 1770's as indicated in Table II.

Table III shows R. A. Brock's estimates of the quantity of tobacco exported from Virginia in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, while Table IV sets forth David Macpherson's compilations of British imports of tobacco from all sources, 1761-1775.1 Table V indicates the number of hogsheads exported from each of five customs districts in Virginia, 1745-1756, 1769, and 1773. Most statistical

| Product | Great Britain | Ireland | Southern Europe & Wine Is. | Africa | W. Indies | Coastways | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ashes | — Pot | cwt. | 6 | 6 | |||||

| Pearl | tons | 6 | 6 | ||||||

| Beer, Cyder, etc. | bbls. | 11 | 22 | 33 | |||||

| Brass, | old | lbs. | 350 | 200 | 550 | ||||

| Bricks | No. | 8,700 | 111,500 | 120,200 | |||||

| Candles | — Spermacato | lbs. | 175 | 175 | |||||

| Tallow | lbs. | 200 | 450 | 1,300 | 1,950 | ||||

| Chocolate | lbs. | 200 | 5,406 | 5,606 | |||||

| Cocoa | lbs. | 2,400 | 2,400 | ||||||

| Coffee | cwt. | 18 | 18 | ||||||

| Cotton | lbs. | 2,484 | 6,633 | 9,167 | |||||

| Feathers | lbs. | 5,192 | 5,192 | ||||||

| Flax | lbs. | 1,772 | 1,772 | ||||||

| Flaxseed | bush. | 48 | 64 | 2,297 | 2,409 | ||||

| Furs | — Fox | No. | 1,800 | 1,800 | |||||

| Mink | No. | 25 | 25 | ||||||

| Otter | No. | 100 | 100 | ||||||

| Furtick | [Fustick?] | cwt. | 559 | 559 | |||||

| Gensing | lbs. | 4,670 | 4,670 | ||||||

| Gin | cases | 5 | 5 | ||||||

| Grain | — Corn, Ind. | bush. | 72,071 | 4,699 | 304,431 | 180,367 | 561,568 | ||

| Oats | bush. | 7,896 | 5,419 | 13,315 | |||||

| Rye | bush. | 300 | 2,047 | 2,347 | |||||

| Wheat | bush. | 24 | 3,146 | 94,366 | 100,858 | 198,394 | |||

| Hemp | bush. | 52 | 52 | ||||||

| cwt. | 23 | 23 | |||||||

| Hides | cwt. | 571 | 571 | ||||||

| Indigo | lbs. | 2,423 | 2,423 | ||||||

| Iron | — Bar | Tons | 96 | 17 | 45 | 158 | |||

| cwt. | 27 | 22 | 9 | 58 | |||||

| Cast | cwt. | 8 | 8 | ||||||

| lbs. | 82 | 82 | |||||||

| Pig | tons | 1,499 | 15 | 4 | 1,518 | ||||

| cwt. | 44 | 44 | |||||||

| Wrought-axes- | No. | 221 | 221 | ||||||

| Tons | 40 | 40 | |||||||

| Lard | lbs. | 15,450 | 36,230 | 51,680 | |||||

| Leather | lbs. | 251 | 5,000 | 5,251 | |||||

| Lemons & oranges | No. | 48 | 48 | ||||||

| Logwood | tons. | 16 | 16 | ||||||

| Lumber | — boards & planks | ||||||||

| Cedar | ft. | 1,100 | 1,100 | ||||||

| Oak | ft. | 48,964 | 48,964 | ||||||

| Pine | ft. | 30,359 | 8,495 | 2,027,368 | 7,790 | 2,074,012 | |||

| Handspikes | No. | 4,101 | 1,272 | 48 | 5,421 | ||||

| Hoops | No. | 9,388 | 158,790 | 168,178 | |||||

| Lock Stocks | No. | 32,060 | 32,060 | ||||||

| Oars | ft. | 21,265 | 2,496 | 23,761 | |||||

| Shingles | No. | 75,380 | 8,671,666 | 94,600 | 8,841,646 | ||||

| Staves | No. | 2,681,220 | 78,000 | 53,260 | 2,630,290 | 100,770 | 5,543,540 | ||

| Timber | |||||||||

| Cedar | Tons. | 1 | 18 | 19 | |||||

| ft. | 32 | 62 | 94 | ||||||

| Oak | tons. | 557 | 557 | ||||||

| ft. | 83 | 68 | 151 | ||||||

| Pine | tons. | 183 | 183 | ||||||

| ft. | 12 | 12 | |||||||

| Trunnells | No. | 4,100 | 3 | 4,103 | |||||

| Mahogany | ft. | 3,680 | 642 | 4,322 | |||||

| Meal | bush. | 546 | 546 | ||||||

| Molasses | gals. | 2,079 | 2,079 | ||||||

| Naval Stores | Pitch | bbls. | 12 | 134 | 51 | 197 | |||

| Tar | bbls. | 21,138 | 855 | 888 | 22,881 | ||||

| Turpentine | bbls. | 1,411 | 2,894 | 808 | 5,113 | ||||

| Masts | No. | 49 | 49 | ||||||

| Oil, Train | gals. | 94 | 94 | ||||||

| Ore, Copper | tons. | 2 | 2 | ||||||

| cwt. | 16 | 16 | |||||||

| Provisions | Beef & Pork | bbls. | 5,289 | 1,481 | 6,770 | ||||

| Bread & Flour | tons. | 1 | 1,193 | 11 | 1,439 | 641 | 3,285 | ||

| cwt. | 24 | 4 | 78 | 10 | 45 | 41 | 202 | ||

| Butter | lbs. | 910 | 4,200 | 29,510 | 34,620 | ||||

| Cheese | lbs. | 200 | 200 | ||||||

| Fish-Dried | Qls. | 20 | 20 | ||||||

| Pickled | bbls. | 6 | 3,183 | 836 | 4,025 | ||||

| Hams | bbls. | 172 | 172 | ||||||

| Peas, etc. | bush. | 1,679 | 14,849 | 4,764 | 21,292 | ||||

| Potatoes | bush. | 1,327 | 1,327 | ||||||

| Rum- | New England | gals. | 3,530 | 15,201 | 18,731 | ||||

| West Indian | gals. | 40,472 | 41,012 | ||||||

| Salt | bush. | 13,350 | 13,350 | ||||||

| Sassafras | cwt. | 99 | 99 | ||||||

| Shoes | prs. | 107 | 107 | ||||||

| Skins - | Bear | no. | 47 | 47 | |||||

| Beaver | lbs. | 1,850 | 1,850 | ||||||

| Deer-Dressed | no. | 1,842 | 1,842 | ||||||

| lbs. | 29,695 | 29,695 | |||||||

| Raw | no. | 6,029 | 6,029 | ||||||

| lbs. | 144,657 | 144,657 | |||||||

| Racoon | no. | 102 | 102 | ||||||

| Snakeroot | lbs. | 900 | 900 | ||||||

| Soap | lbs. | 200 | 950 | 1,150 | |||||

| Stock, | Live-Horses | no. | 5 | 5 | |||||

| Sheep | no. | 20 | 20 | ||||||

| Poultry | doz. | 57 | 57 | ||||||

| Sugar - | Loaf | lbs. | 1,768 | 1,768 | |||||

| Brown | cwt. | 680 | 329 | 1,009 | |||||

| Tobacco | hhds. | 79,614 | 79,614 | ||||||

| lbs. | 84,755,274 | 147,036 | 36,655 | 84,938,965 | |||||

| Walnut-Black- | Boards | ft. | 9,650 | 3,939 | 1,050 | 14,639 | |||

| Timber | tons. | 46 | 1 | 47 | |||||

| ft. | 98 | 98 | |||||||

| Wax - | Bees | lbs. | 13,400 | 2,600 | 11,430 | 27,430 | |||

| Myrtle | lbs. | 1,600 | 1,600 | ||||||

| Whalefins | lbs. | 500 | 500 | ||||||

| Wine | tons. | 4 | 4 | ||||||

| gals. | 464 | 336 | 800 | ||||||

| Tobacco, 96,000 hogsheads, at 8£ | £ 768,000 |

| Indian corn, beans, pease, &c. | 30,000 |

| Wheat, 40,000 quarters, at 20 s. | 40,000 |

| Deer and other skins | 25,000 |

| Iron in bars and pigs | 35,000 |

| Sassafras, snake-root, ginseng, &c. | 7,000 |

| Masts, plank, staves, turpentine, and tar | 55,000 |

| Flax-seed, 7,000 hogsheads, at 40 s. | 14,000 |

| Pickled pork, beef, hams, and bacon | 15,000 |

| Ships built for sale, 30 at 1,000 £ | 30,000 |

| Hemp 1,000 tons at 21 £ | 21,000 |

| TOTAL | £1,040,000 |

|---|

| Year | Crop (in Pounds) |

|---|---|

| 1619 | 20,000 |

| 1620 | 40,000 |

| 1621 | 55,000 |

| 1622 | 60,000 |

| 1628 | 500,000 |

| 1639 | 1,500,000 |

| 1640 | 1,300,000 |

| 1641 | 1,300,000 |

| 1688 | 18,157,000 |

| 1704 | 18,295,000 |

| 1745 | 38,232,900 |

| 1746 | 36,217,800 |

| 1747 | 37,623,600 |

| 1748 | 42,104,700 |

| 1749 | 43,188,300 |

| 1750 | 43,710,300 |

| 1751 | 42,032,700 |

| 1752 | 43,542,000 |

| 1753 | 53,862,300 |

| 1754 | 45,722,700 |

| 1755 | 42,918,300 |

| 1756 | 25,606,800 |

| 1757 | short crop |

| 1758 | 22,050,000 |

| Date | England (pounds) | Scotland (pounds) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1761 | 47,065,787 | 24,048,380 | 71,114,167 |

| 1762 | 44,102,491 | 27,339,433 | 71,441,924 |

| 1763 | 65,173,752 | 31,613,170 | 96,786,922 |

| 1764 | 54,433,318 | 26,310,219 | 80,743,537 |

| 1765 | 48,306,593 | 33,889,565, | 82,196,158 |

| 1766 | 43,307,453 | 32,175,223 | 75,482,676 |

| 1767 | 39,140,639 | 29,385,343 | 68,525,982 |

| 1768 | 35,545,708 | 33,261,427 | 68,807,135 |

| 1769 | 33,784,208 | 35,920,685 | 69,704,893 |

| 1770 | 39,187,037 | 39,226,354 | 78,413,391 |

| 1771 | 58,079,183 | 49,312,146 | 107,391,329 |

| 1772 | 51,493,522 | 43,748,415 | 95,241,937 |

| 1773 | 55,928,957 | 44,485,194 | 100,414,151 |

| 1774 | 56,048,393 | 40,457,589 | 106,505,982 |

| 1775 | 55,965,463 | 55,927,542 | 111,893,005 |

| Upper James | Lower James | York | Rappahannock | South Potomac | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1745 | 10,991 | 1,381 | 11,118 | 12,332 | 6,659 | 42,481 |

| 1746 | 10,799 | 1,372 | 11,015 | 10,745 | 6,311 | 40,242 |

| 1747 | 9,355 | 1,718 | 12,895 | 12,132 | 5,704 | 41,804 |

| 1748 | 12,489 | 3,170 | 11,089 | 13,052 | 6,983 | 46,783 |

| 1749 | 11,509 | 3,150 | 10,970 | 15,012 | 7,346 | 47,987 |

| 1750 | 12,974 | 2,218 | 13,802 | 14,331 | 5,242 | 48,567 |

| 1751 | 10,858 | 2,525 | 12,054 | 13,553 | 7,713 | 46,703 |

| 1752 | 13,530 | 1,423 | 12,623 | 14,299 | 6,505 | 48,380 |

| 1753 | 18,830 | 2,113 | 15,127 | 16,815 | 6,959 | 59,847c |

| 1754 | 13,900 | 1,181 | 14,878 | 13,512 | 7,332 | 50,803 |

| 1755 | 13,739 | 918 | 15,344 | 11,963 | 5,723 | 47,687 |

| 1756 | 7,262 | 1,096 | 6,918 | 8,531 | 4,645 | 28,452 |

| 1768a | 15,860 | 1,504 | 5,668 | 9,105 | 5,512 | 39,623d |

| 1769a | 17,825 | 1,993 | 8,225 | 9,920 | 9,143 | 50,222e |

| 1772a | 24,900b | ---- | 8,634 | 14,549 | 10,716 | 65,208f |

| 1773a | 27,592 | 4,674 | 8,248 | 13,244 | 10,541 | 69,587g |

1768, Jerman Baker to Thomas Adams, January 8, 1769, Adams Papers (Virginia Historical Society).

1769, Virginia Gazette (Rind), November 2, 1769.

1772, Virginia Gazette (Purdie & Dixon), November 19, 1772.

1773, Ibid., November 11, 1773. 20 data of the eighteenth century, though, should be regarded with care. Customs valuations were based usually upon traditional rates or were the result of guesswork. Even figures of quantities are subject to the limitation that they record only the goods and commodities which passed through the Customs. Smuggling varied with the rate of duties, which determined the profitability of the practice and with the degree of law enforcement. The extent of smuggling of heavily taxed tobacco is not known, but there is evidence that it was considerable, However, when the limitations of the statistics on the tobacco trade, as well as those on other types of commerce, are taken into consideration, these data do seem to give rough indications of over-all growth and trends. 2

As for the trends shown by these tables, the tremendous expansion of production from 1704-1753 reflects the settlement of the Piedmont.3 The small exports of 1756-1758 appear to have resulted from war-time dislocations. The sharp increase which the data show in British imports after 1771 is questioned by one authority, who comments that the rise "is so sudden as to suggest either a fault in the statistics or some change in trade methods."4

The two principal varieties of tobacco were sweet-scented and Oronoko. The former, grown principally in the sandy loams of the peninsula between the James and York, was distinguished by its round leaf, fine fibres, and mild flavor. Oronoko was coarser, bulkier, 21 and stronger in flavor, and its production more widely distributed through the tobacco-growing areas of the colony. Sweet-scented, which commanded a premium in English markets during much of the seventeenth century, was gradually displaced during the eighteenth century by better grades of Oronoko. Although several subvarieties of the latter were recognized, almost all tobacco was officially classified simply as Oronoko by the latter part of the eighteenth century.5

The quality and quantity of tobacco produced on any plantation depended upon two factors: the type and condition of the soil and the care with which the planter cultivated and prepared his tobacco for market. According to an eighteenth-century authority,

the lands which are found to answer best, in their natural state in Virginia, are the light red, or chocolate coloured mountain lands; the light black mountain soil in the coves of the mountains, and the richest low grounds. Hence has arisen the general reputation of the Virginia tobaccos, and, chiefly, the local reputations of particular tobaccos brought to market: as, for example, James's River tobacco, Tayloe's Mountain Quarter tobacco, &c. which are preferred.6

Since "a Virginian never thinks of reinstating or manuring his land until he can find no more land," the exhausting nature of tobacco cultivation generally required abandonment in three or four years. Although exhausted land returned to timber regained some of its fertility in twenty years or so, it was less productive than new lands.7 One planter among many who were looking to the mountain area for fresh 22 tobacco land, reported in 1771 that those "who have moved from Gloster to Frederick make near 5 times as much as they did down here."8 Tobacco produced on new land was likely to be of better quality than that from a previously worked tract, which was implied by a planter who insisted to a London merchant that "[this tobacco was] made at my Plantation in Brunswick on fresh Land."9

Equally important in producing tobacco of good quality was the method of cultivation, which consisted of a series of tasks which required painstaking care. Each of the processes — seed-planting, transplanting, topping, suckering, worming, and cutting — had to be undertaken at a proper time of growth under precise weather conditions.10 During preparation for marketing, stripping, stemming, and prizing into hogsheads — only long experience could determine whether the plant was in case for the next operation, that is, "in a condition which will bear handling and stripping, without either being so dry as to break and crumble, or so damp as to endanger a future rotting of the leaf,"11 No profit would be derived by the planter who "should blunder in this one point only, then wanted to complete a marketable staple, and become thus involved in a total loss of his whole crop, and have the expences to pay into the bargain, for bringing an unmerchantable article to market."12

Buyers usually were willing to pay a premium for quantities 23 of tobacco cultivated by men of experience and good reputation who worked good lands. This tobacco was then expected to yield a premium in English markets, as indicated by this complaint of an early eighteenth-century tobacco buyer to his English correspondent:

I must make hold to mention a great Evil that I think to be in ye Tob[acc]o. Trade which is in Selling a several persons Tobo. Together to one Man So y[a]t. if mine is never so good beyond the rest I shall have no more for it, than he that owns ye meanest sort in that parcell Altho my Tobo. deservs a penny p[er] lb. more. Therefore earnestly desires my Tobo. may be sold it by. Self without being lumpt of with others. for I am well Satisfyed (for ye Quantity of it) there is not a better parcill of Tobo. Comes from our parts of ye Country and I believe not nigh so good I can assure you the greatest part of it has cost me above 7 £ sterl[ing] p h[ogs)h[ea]d before goeing on Board of the Ship Therefore hopes it may come to a good Mark[e]t. with You to fetch me so much Money to Enable me to give an Encouraging price to those that will take Care to make such good Tobo.13

In order to improve the quality and thus the reputation and price of Virginia tobacco, the inspection law of 1730 required that all Tobacco destined for export be brought to public warehouses, located at convenient points on the navigable rivers, generally about twelve to fourteen miles apart. If the public inspectors, two in number after 1732, approved the tobacco as "good, sound, well-conditioned, and merchantable, and free from trash, sand, and dirt," they were to place an official stamp upon the hogshead and issue a certificate to the planter. Trash was to be burned. The tobacco note, which was a title to the tobacco and changed hands when the planter sold or exported the hogsheads, was accepted for payment of taxes and possessed limited negotiability. Crop notes listed specific hogsheads by mark and number, while transfer notes, representing tobacco brought in loose bundles, 24 entitled the bearer to the same quantity and type of tobacco.14

In spite of some opposition in the 1730's, inspection proved successful in its goal of removing the poorest grades of tobacco from trade, to the mutual benefit of merchant and planter. Occasionally, inspectors were lax, as was pointed out by one merchant to his back- country storekeeper in 1772:

I wish you would discourage your Customers as much as you can with prudence from carrying their Tobo. to Ozburnes Warehouse [as] that Inspection is under a very bad character at present in England, the planters goes out of their way to it on Acc[oun]t. of its being favourable. 15But another merchant was more optimistic, stating that the inspectors at Aquia on the Potomac "are great villains, but I hope they will soon be turned out."16

Major Markets. According to British law, tobacco was on the list of enumerated commodities, that is, commodities which could be exported only to England. Furthermore, the Navigation Acts required that tobacco, like all colonial products, could be exported only in ships which were built, owned, and manned by English (including English colonial) subjects.17

By the beginning of the eighteenth century, London had out-distanced all outport competitors to become the major British tobacco market. While Bristol still held an important position as distributor in the domestic market, London in 1720 handled at least two-thirds of the tobacco imported by Great Britain.18

However, from the early part of the century, Glasgow began to challenge London's supremacy. The Act of Union of 1707 removed the legal disabilities of Scottish trade with the colonies by placing Scotland within the closed commercial system of Britain. The rapid rise of Glasgow is illustrated in Table VI, which shows tobacco imports of Scotland at specified years from 1707-1775. Scotland's relative growth was even more striking. As late as 1738, the Scottish ports accounted for only ten per cent of total British imports. This rose to 20 per cent in 1744, 30 per cent in 1758, 40 per cent in 1765, and almost 52 per cent in 1769, and declined slightly to 45 per cent on the eve of the American Revolution.19 Table VII shows the destination of the 1765-1766 crop from the upper James, which exported more tobacco than any other district in Virginia.

London merchants were inclined to view Glasgow's growth as the result of lax enforcement by customs officials in Scotland, but whatever merit might have derived from this charge was removed by the Tobacco Act of 1751, which placed more rigid controls on tobacco importations. The most recent interpretation of Glasgow's growth takes into consideration more fundamental factors. In the first place, the route north of Ireland was the shortest and safest route to Virginia. Liverpool

| 1708 | 1,450,000 |

| 1715 | 2,500,000 |

| 1722 | 6,000,000 |

| 1741 | 8,000,000 |

| 1743 | 10,000,000 |

| 1745 | 13,000,000 |

| 1752 | 21,000,000 |

| 1753 | 24,000,000 |

| 1760 | 32,000,000 |

| 1771 | 47,000,000 |

| Destination | Hogsheads |

|---|---|

| London | 2,470 |

| Bristol | 1,493 |

| Liverpool | 1,730 |

| Whitehaven | 1,877 |

| Hull | 165 |

| Penryn | 404 |

| Falmouth | 95 |

| Scotland | 11,176 |

| Total | 19,410 |

From the mid-seventeenth century, when the demand for tobacco in England began to level off, Continental markets expanded to keep pace with the rising production in English America. By the mid-eighteenth century, the Chesapeake colonies were supplying tobacco to all of Europe. Indeed, about 90 per cent of the total tobacco imports of England and Scotland were reexported in the five years 177G-1774.21

Table VIII shows the leading European customers for British tobacco in 1772. Although Amsterdam was an important processing and distributing center for all the Continent in the seventeenth century, European buyers more generally by-passed the Amsterdam market to purchase

| England (Pounds) | Scotland (Pounds) | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | 990,873 | ------ | 990,873 |

| Denmark & Norway | 2,573,284 | 812,650 | 3,385,934 |

| East Country | 265,019 | ------ | 265,019 |

| East Indies | 53,915 | ------ | 53,915 |

| Flanders | 7,150,737 | ----- | 7,150,737 |

| France | 7,343,883 | 24,406,240 | 31,750,123 |

| Germany | 11,953,577 | 1,982,347 | 13,935,924 |

| Greenland | 1,521 | ------ | 1,521 |

| Holland | 14,371,835 | 14,629,050 | 29,000,885 |

| Ireland | 1,855,923 | 4,333,850 | 6,189,773 |

| Italy | 1,378,156 | ------ | 1,378,156 |

| Madeira | 100 | ------ | 100 |

| Russia | 22,048 | ----- | 22,048 |

| Spain | 229,722 | ------ | 229,722 |

| Sweden | 1,076,078 | ------ | 1,076,078 |

| Venice | 25,209 | ------ | 25,209 |

| Channel Islands | 825,111 | ------ | 825,111 |

| North America | 170,510 | 48,446 | 218,856 |

| West Indies | 94,474 | 25,355 | 119,829 |

| Total | 50,386,925 | 46,389,518 | 96,776,443 |

| [50,381,975] | [46,237,938] | [96,619,913] |

Channels of Trade: The Consignment System. When the merchantable tobacco was ready for shipment, there were two principal methods of marketing: the consignment system and the direct purchase system.

28Those using the consignment method shipped their tobacco to a British merchant who supervised the unloading, paid the customs duties, carted the tobacco to warehouses, and sold the commodity at the best market price. Title was retained by the American consignor, who bore the risks and expences of transportation and marketing. The British commission merchant, acting as an agent in performing the marketing functions, generally received 2 ½ per cent of the gross sales. In addition to selling tobacco, the British merchant attended to many of the other economic needs of the Virginia planter — providing transportation, securing insurance, and supervising the purchase of goods. Each year the account current was prepared, showing net sales of tobacco, after all expenses were deducted, and the cost of goods ordered by the planter.24

Most of the consignment business was centered in London, although some of the outports, principally Bristol, held a share of this type of trade. To transact the selling of 741 hogsheads of tobacco in 1769 required a capital of £6,000 plus the use of £12,000 of borrowed funds, according to the experience of John Norton & Sons, not the largest London tobacco merchants.25 To some extent, the scale of business of the individual consignment merchant was limited by the amount of personal attention which he had to devote to each customer. William Reynolds told George Norton, son of John Norton, in 1774 that he was "really apprehensive the very large quantity he [i.e., John Norton ] had now shipt him must necessarily prevent his paying that 29 particular attention a Man might do with 5 or 600 h[ogs]h[ead]s.26 In Virginia, many of the large planters, who were the most prevalent consignors, consigned not only tobacco produced on their own plantations but also tobacco purchased from small planters and farmers. There were also merchants like Robert Anderson in the early eighteenth century who purchased tobacco for consignment.27

In most cases, the commission merchant maintained an agent or employee in Virginia to solicit consignments. John Hatley Norton, first acting as agent for his father and then as junior partner, spent many days "riding Journeys in such a hot Country, [which] must be very fatiguing."28 Ship captains, too, travelled around the county courts to contact prospective customers. When the English firm did not have its own full-time agent in the colony, it usually retained the services of a Virginia merchant to supervise its business in the colony, particularly the collection of debts. The normal commission for settling accounts and making remittances appears to have been 5 per cent, but Charles Steuart offered in 1751 to transact business for Bowden & Farquhar of London for 2 ½ per cent.29

The most important benefits derived by the consigning planter were the realization of the full market price for tobacco in England and the credit for necessary imported goods. The system, though, rested on mutual trust: that the merchant sold the consignment of tobacco for the best market price and that the planter shipped tobacco in sufficient 30 quantities to cover the cost of the goods which he ordered from England. Many consignors undoubtedly were well satisfied that their English correspondents exerted every effort on their behalf, as in the case of one Virginian who wrote: "I have lost considerably by my last Consignment of Tob[acc]o, but this I know you could not help."30 Considerable understanding of rapidly fluctuating markets in Britain was necessary for this comment:

You seem to be uneasy that you shall not be able to render as good an Acc[oun]t. of Sales for the Tob[acc]o. of last Year as you did for that of the preceeding; but all reasonable Men will make Allowance for the Difference of Circumstances, and the unreasonable are not to be satisfied with any Thing.31

However, all tobacco growers were not reasonable, and it was inevitable that the great distance between merchant and planter would result in some misunderstanding. Some Virginians complained about lack of care in transacting business, as did Robert Anderson in the early eighteenth century:

I find by your Measures to me that row Concerns is not worth Your minding, for I have not been used to be obliged to go to other Men to Know my Affairs till being Concerned with you and I was in hopes your Principles did not allow makeing such differences in Respect to Persons but since I find it is so I desire you to Settle my Acc[oun]t.32At times, the ship captain was guilty of an oversight in loading tobacco. The master of one of John Norton's ships was the target of this criticism:

I had advised you in my last that I had shipt you six H[ogs]h[ea]ds of Tobacco, and I had actually delivered orders for them, but I find Robinson was kind 31 enough to leave them out, and he has treated Mrs. Chamberlayne in the same manner. I think it strange that your particular Friends should be thus treated, many others complain and I wish it may not hurt your interest with them.33

Many complaints were directed to what the planter regarded as excessive selling charges. The nominal commission of 2 ½ per cent of gross sales actually amounted to as much as 8-10 per cent of the net proceeds, since the commission was levied against all charges and duties. Fixed charges — freight, insurance, primage, wharfage, porterage, lighterage, storage, and customs duties — generally amounted to 75 to 90 per cent of the price to the consumer but sometimes resulted in a loss to the producer. Because these charges varied little whether tobacco prices were high or low, a small percentage change in consumer prices, when shifted back to the produced, made a comparatively large percentage difference in prices received.34

Endless controversies developed over the prices end quality of goods ordered by the planters. If prices were higher than anticipated, or the condition and quality less than perfect, or the goods ordered not precisely what the planter had in mind (whether or not his specifications 32 had been precise), the commission merchant was blamed.35

On the other side, planters were often guilty of overdrawing on their accounts. Some expected excessive advances as a condition of consignment to a particular merchant, as one Virginian observed in the 1770's:

Some people are so very unreasonable in their Expectations to have Money advanced, that it is extremely difficult to avoid giving them Umbrage. The Misfortune is that, if one Merch[an]t. will not comply with their Desires, they fly to another.36

While many of these charges levied by both sides were true and the causes of the complaints valid, most planters overlooked the basic factors. As one recent writer has pointed out:

Much of the criticism directed at the merchants resulted from wistful refusal or inability to perceive that fundamentally market conditions could not be controlled by either the merchants or the planters. In making whipping boys of unreliable merchants, the planter succeeded in glossing over other important issues. Among them was the evident fact that in Virginia overproduction was chronic. The demand for tobacco could grow only as the taste for tobacco became more widespread, new markets were exploited, and the population of Europe increased. All of these things came during the eighteenth century, but in the meantime Virginians produced for potential, rather than actual markets.37

Although the consignment system was used almost universally in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, by the 1750's it 33 accounted for only about one-quarter of Virginia's tobacco exports.38 James Parker, Norfolk merchant, may have exaggerated in 1770 that "the trade of Consigning Tob[acco] to the London Merch[an]ts seems to be nearly at an end,"39 but it does seem that by the 1770's most of the consignment business was carried on from the older declining Tidewater area of the colony.

Channels of Trade: The Direct Purchase of Tobacco. Under the direct purchase method, in contrast to consignment, title to the tobacco passed from the producer to the agent or employee of a British firm, which assumed the responsibility, risks, and costs of shipping and marketing the produce in Great Britain.

As indicated previously, settlement of the Piedmont resulted in a great expansion of tobacco production and in new marketing problems, since ocean-going ships could not navigate into the region. However, London merchants, who controlled much of the consignment trade of the Tidewater, were reluctant to pursue vigorously the business of this new area. Virginia merchants, as well as those from the English outports, lacked sufficient capital to expand operations. Into this situation stepped the Scottish merchants to take advantage of a potentially lucrative commerce. "They were not accustomed to the specialization in trade that characterized the English mercantile enterprises, so they could adapt themselves to the demands of the Virginia situation 34 more readily than could most English merchants."40

Many of the early Scottish traders were travelling merchants. Indeed, they were often called the "Scots peddlers." Each venture appears to have been financed and organized separately by groups of merchants, who appointed one of their number as supercargo to supervise the sale of goods and the purchase of tobacco.4l

By the 1730's, a more permanent organization was in operation. Stores were located at likely trading locations; here the factors42 the Glasgow firms supervised the purchase of cargoes of tobacco and sold the goods shipped out from Britain. The fall line towns, where trans-shipment of goods to and from the Piedmont took place, became centers of Scottish mercantile activity. Factors operated stores in such places as Alexandria, Richmond, Fredericksburg, Falmouth, and Petersburg. Elsewhere Scots became entrenched in Norfolk and in the Northern Neck.43 Although the Scots were most important in the direct purchase method, some English firms operated in this manner. Roger Atkinson of Petersburg purchased tobacco for the Lydes of London, and Harry Piper of Alexandria for Dixon & Littledale of Whitehaven.44

35Factors received a commission, usually of five per cent on tobacco purchased and ten per cent on goods sold. Many, like Francis Jerdone in Louisa County, also engaged on their own account in other types of business such as the West India trade and sometimes speculated in consignments of tobacco which they purchased.45

By the 1760's and 1770's, tobacco purchasing became a large-scale business, as several Glasgow firms established extensive chains of stores. The Cuninghame interests, the largest by 1774, operated seven stores in Maryland and fourteen in Virginia, the latter located at Richmond, Amherst, and Rocky Ridge in the upper James valley, at Petersburg, Cabin Point, Mecklinburg Courthouse, Brunswick Courthouse, and Halifax on the south side of the James River, at Dumfries on the Potomac, at Falmouth, Fredericksburg, Fauquier Courthouse, and Culpeper in the upper Rappahannock valley, and at Caroline Courthouse.46 Companies controlled by John Glassford, another of the leading Glasgow "Tobacco Lords," operated stores throughout Maryland and Virginia, including those at Quantico, Dumfries, Fredericksburg, Falmouth, Colchester, Cabin Point, Rocky Ridge, Boyd's Hole, and Alexandria.47

Administration of a chain of stores required more organization than did maintenance of a connection with a single factor or even several 36 factors. In charge of the American operation was a chief factor — sometimes a partner, as was Neil Jamieson, who supervised the Glassford stores in Virginia. Jamieson, in addition to his duties as chief factor, engaged in an extensive trade to the West Indies and southern Europe on his own account.

The chief factor was alert to locate new stores in likely places to attract customers. James Robinson, chief factor in Virginia for William Cuninghame and Company, indicated some of the strategy involved in store location in his instructions to the manager of a newly established store at Culpeper Courthouse:

The more immediate motive for fixing this store was to be a Check on Mr Lawsons transactions at this store in the little fork of Rappahannock & to prevent any Other Company occupying a situation at the Courthouse, which appears to your employers a suitable place for a Settlement being in a Good Tobacco County and in the Center of the County.48The new storekeeper, though, was cautioned not to deal with people "who are Allready Customers to their [i.e., the Companys] Frederick[sbur]g or Falmouth Stores as they Can gain no additional Int[e]rest or influence by such." He was further instructed to build up his trade "with As little noise and parade as possible for fear of Alarming others, and puting them on the same scheme before the store is well established."49

A similar element of business strategy in store location is shown in this communication from Leedstown factor to a London firm:

There is now a Scotch Store fixed within about 6 Miles of Leeds, the principal director has been pleased to give out that he has done it purely to take away the large Custom [of] your store at Leeds and to try if you have money to Carry on & support the Trade — This I think is a very [b]add declaration — I have it now in my power 37 to fix a store at a good Wareho[use] on Poto[mac] about 6 Miles above this Gentleman, w[hi]ch I am determined to do.50

Each store was in charge of a salaried manager. Probably representative were the arrangements made by James Robinson in hiring storekeepers for the Cuninghame stores. For the management of the Culpeper store Robinson agreed to pay £60 sterling annually for a period of five years.51 At Petersburg, where operations were more extensive, an experienced storekeeper received £80 sterling the first year, £90 the second year, and £100 annually for the remainder of the five year term.52 In addition, the storekeeper was allowed living costs and an expense account. Alexander Blair expected to receive £20 "yearly for Incident Charges" in the operation of the Glassford store at Fredericksburg.53

The storekeeper was expected to devote all of his time and energy to the operation of the store. Contracts usually provided that the storekeeper

be debarrd from all manner of Trade whatever directly or indirectly on his own account or on any other account than his constituents whose business of every kind he is to execute to the utmost of his ability as directed from time to time.5438 James Robinson, in dismissing the manager of the Cuninghame store at Fauquier after the latter's marriage, maintained that the Company "cannot agree to be served by a married man, if a single one can be got, thinking the former must often be necessary call'd from their Business by his family affairs."55

The storekeeper was advised "Strongly from forming Acquaintance with the Idle and profligate part of your County." If business affairs did not keep the storekeeper busy, "any Intervall may be filled up much to his Improvement, by read[in]g Good Authors who Generally prove the best friends."56 James Robinson promptly dismissed his storekeeper at Dumfries, who "gave a loose to dissipation" by "a purchase … of a Servant Girle which he kept for some time; and gaming to excess."57

In most cases, the post of storekeeper seems to have been filled by a young Scot. David Ross's sentiments probably reflected those of other merchants, who avoided hiring an American:

from the manner of Educating the Youth of this Country, there [sic] untoward disposition & reluctance to confinement & drudgery induces me to intreat you not to Employ any more of them unless it be as a temporary assistant. I see from repeated experience that after a man has been at much pains with them & might reasonably expect he had so moulded their dispositions as to act & think like himself, he is at once disappointed & finds after all he cannot deppend on them as their heads at that time a day are generally bent another way & they have too many passions to sacriffice before they can be serviceable to any man — I speak in general terms — there are exceptions —5839 Some claimed that the large Scottish firms followed a policy of nepotism, as indicated by this comment on locating a position in Virginia for a young man: "I was in hopes this afternoon to have got him fix1d on York River in a very extensive & broad new Concern, but when the budget was open'd, an advocate appeard for the Supra Cargoes brother, which you may easily believe prevaild."59

Many believed that the road to wealth and success in business began with employment as a storekeeper for a tobacco firm, but James Parker, wealthy Norfolk merchant, disagreed. In discussing a suitable position for a young nephew of a friend in Scotland, Parker pointed out his belief that unless the young man "had a Sufficienty to purchase a small Share of one of those concerns after he had Served 4 or 5 Years in the business the Chance is against him" succeeding. Parker did not have fond memories of his own period of employment in the organization of Alexander Spiers, "the Mercantile God of Glasgow," "I was a factor, & had I been a third or fourth Cuzin to Some of the principalls, I suppose, with a patient, dilligent, Saving & Subservient disposition, I might have jogged on in a State of dependance to this day."60

In addition to the storekeeper, one or more clerks or assistants were employed in the operation of the store. Wages probably varied greatly according to experience. Neil Jamieson engaged a clerk, evidently one with some experience, for his store at Boyd's Hole at an annual salary of £40 sterling.61 A beginning clerk might receive as little as £5 per 40 year, plus room and board, although annual increases were provided in this case to bring the salary to £25 in the final year of a five year contract.62 Since clerks might be eligible for promotion within the organization, managers of the Cuninghame stores were directed annually to "transmitt [to] the Company the Names of the Assistants under your directions; the time they have Served with their Characters & Capacitys in the most Impartial manner."63

Negro slaves were used for work around the store. James Robinson employed fourteen slaves in the operation of the Cuninghame store at Falmouth: five as house servants, one to load and unload ships, one as carpenter, four to man a sloop, and three as crew of a schooner.

Although the early stores were probably strictly utilitarian in architecture and furnishings, many of those of the 1770's were elaborate affairs. The Cuninghame store at Fredericksburg was valued in 1775 at £1,700, not including the goods in stock or slaves.65 Arthur Morson estimated the value of the Falmouth property, consisting of a storehouse and more than one warehouse, which he used to conduct the business of the Glassford firm, at £440.66 In 1774, Neil Jamieson 41 considered leasing, as a site for the Glassford store, property at Cabin Point which included a dwelling, a two story store building and counting house, kitchen, slave quarters, smoke house, stable and carriage house, pasture, and "a Large new Granarie," for an annual rent of £50 local currency.67 When a company undertook trade in a new area, "Houses on Rent will answer better than to build for some time, untill it was known if the Trade turns out well."

Total operating costs of stores varied greatly, of course, but an account of costs of one of Neil Jamieson's stores in Pasquotank County, North Carolina, a produce rather than a tobacco area, does indicate something of the break-down of expenses. Of the total amount of £300 spent for store operation in 1772, the sum of £150 represented the "Board Wages &c" of Matthias Ellegood "to Carry on the Management of a Store at his house," £20 "a Young Mans Board &c," £10 for a Negro, £40 for "Buying and sending 2 horses," £40 for the use of storehouses and carts, and £40 for "Victuales [and] liquors in the House on the ocasion through the year for Customers &c."69

The primary purpose of the store system was of course to purchase tobacco, but it was necessary for the storekeeper to keep on hand an assortment of European goods and West Indian commodities. The greater the assortment of goods, the more likely was the storekeeper to attract customers. One factor, who operated a store at Leedstown, complained 42 to his employer: "I hope you do not intend these goods as a proper supply of Fall Goods for y[ou]r. store, if you do, your Customers must go to some other Merch[an]t."70 A backcountry storekeeper, in Mecklinsburg County, wrote to Neil Jamieson:

The many Stores in the neighbourhood which of consequence causes a rivalship oblidge me to keep a better assortment both of European & W[est] India Goods than what I would else do — Let me beg of you to send the Sugar as expeditiously as in your power & [as] good of its kind which will stop the murmering of the people.71The storekeeper might have to accept wheat, corn, and other commodities besides tobacco, but these were to be regarded as "but Secondary & Subservient objects to that article."72

The chief factor corresponded regularly with his storekeepers, informing them of tobacco prices in Europe and in other parts of the colony and reminding them to prepare their semi-annual schemes, or orders, of goods in June and December. In addition, he made periodic personal visits to each of the stores and saw many of the storekeepers at the Meetings of Merchants in Williamsburg.

Each storekeeper was expected to keep the chief factor and the principals in Britain regularly informed of local developments. Adam Fleming, who operated the Glassford store at Cabin Point, wrote to Neil Jamieson:

You think I dont writt you So frequently as I Should do, but I ashure you it is not through any neglect for at Present there is nothing to be purchased at all and my 43 whole Study is to get the goods Disposed of to Good People which I Shall Indeavour to do as far as lys in my power.73Jamieson was probably a particularly demanding taskmaster. Arthur Morson, his storekeeper at Falmouth, commented that "in your next letter you will blame me for neglecting something or other & for the life of me I cannot recollect anything further to add."74

Storekeepers were advised to

be Generous easie affable and free to your Customers pointed and exact in fullfilling your engagements or even your most trivial promises by these methods you will ingage their esteem regard & Confidence and on this plan allone a large and extensive trade can be aquired and Carried on.75Neil Jamieson gave similar advice to his young nephew, who was loading a ship for Europe:

I hope youl be careful to be as Obliging as in Power, to the Gentlemen in Shipping of the Cargo, dont by any means stand on triffeles to Carrie any dispute, … To be obliging and good Naturd always gains friends & Esteem, but to act a Contra part, w[il]l. be hind[er]ing you[r] Self and us to[o], be not too pr one to Pas[s]ion, weight a mat[t]er the[o]roughly before you venture to dispute, and even if you are right, do not glory too much in having the advantage, Young People are too fond of such things but as you are cautioned, I hope you['l]1 be on your guard, and shun the Rack that many young men has Splitt upon.76However, if the storekeeper held "too great an Intimacy with any" of the customers, it "may be attended with bad consequences." 44 Visiting at planters t houses, James Robinson felt, gave them "a pretence of takin[g] great libertys at the Store,"77

The individual storekeeper was responsible for carrying out the policies formulated by the company in Britain and by the chief factor in Virginia. Every storekeeper had to act "pointedly to Orders, indeed if we do not there must be an end of all Business, as they [i.e., the Cuninghame firm in Glasgow] cannot be in any Settled State of Business at home or know what to depend on, If we act at Random."78 The chief factor generally instructed the storekeeper in regard to tobacco price limits, which were based in turn upon information sent to him from Britain. However, successful operations depended also upon the proper pricing of imported goods and prompt collection of debts owed to the store. The storekeeper thus had to know the debt- paying habits of each planter in his neighbourhood and to attend regularly the county courts in the area in which he did business. Goods generally were priced in local currency in terms of an advance over sterling cost; that is, goods which cost £100 sterling in Britain would be priced at £175 in Virginia currency if the advance was 75 per cent. This advance covered the difference in value between local currency and sterling, freight, handling charges, and a profit to the merchandizer. The rate of advance usually varied with the rate of sterling exchange in Virginia and with competitive conditions in an area, but the store-keeper had some leeway in the pricing of individual articles, as these instructions to a new manager of a Cuninghame store show: 45

You are pretty well Acquainted with the general advance laid on goods here, In pricing the present ones you must view the prices your Neighbour setts at, and in regulating prices great regard must be had to the quality of the goods, as you Know goods of the same Cost will not Allways bear the same advance, and some species of goods will bear more than others, the cost therefore must not entirely govern you in the price, judge the Quality therewith and from thence construe what they will bring, In your sales bear in mind that every person ought not to have goods on the same terms It would be unjust as well as imprudent that those people who pay reedy money or Tobacco, Or those on whom you Can depend will make regular payments once every year to the Amount of their dealings should pay as much for Goods As some others, for whom you may advance sums of money, or who it may be supposed Cannot make regular payments, But you must take Care that these Differences in ye prices be as little Known as possible.79

The salaried manager as well as the independent storekeeper had many routine tasks to perform. James Robinson directed his storekeepers in this way:

In the first of September Annually you are to take an exact Inventory of all the Goods & Effects under your Management, and to Shut the old & begin a new Sett of Books; transmitting to your Constituents as Early as may be in your power thereafter, and not latter than the first day of Feby following. Copy of said Inventory list of Outstanding debts due to & by the Store, Account Current founded thereon also Copy of your Cash Acctt, proffitt & Loss, or Intrest Acctt, and that of Charges of Merchandize, and any other paper, Book, or Account which may be required80