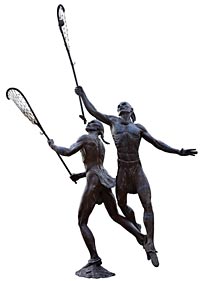

The Native American game of lacrosse could involve hundreds of players and stretch across a mile of uneven fields; contests frequently left injured players. At the Lacrosse Museum and National Hall of Fame in Baltimore, a bronze statue stands in front of the building in tribute to the Indian origins of the game.

Two Cherokee ballsticks, a leather ball stuffed with deer hair, and a beaded sash to hold up the red-and-blue breechcloths.

The sport’s equivalent of the Heisman Trophy rests in the National Lacrosse Museum, the names, tribes, and winners on the base.

The Indian Origins of Lacrosse

by Anthony AveniAnother game is with a crooked stick, and ball made of leather stufft with hair: he wins that drives it from the other between two trees appointed for the goal.

This tantalizing sports tidbit chronicles an early Powhatan Indian version of one of the lasting, and today thriving, gifts of our Native American predecessors, the game of lacrosse. It appears in a document dated 1689 and is titled An Account of the Indians in Virginia. We know the author was a clergyman, likely John Clayton, minister at Jamestown between 1684 and 1686 and an experimenter on a tobacco plantation. He must have possessed more than a passing interest in the Indians, for his manuscript, now in the Newberry Library in Chicago, runs to forty-three pages and deals not only with Powhatan games—for example, he tells us that they also played at wrestling, running, and a game of dice in which they cast split reeds—but with their conjurers, cures for disease, burial customs, music, religion, and, of course, their tobacco “and other productions of the earth with such other things wherewith they traffic.”

Another chronicler of the Virginia Indians, William Strachey, writes in his 1612 Historie of Travel into Virginia Britanica that Powhatan adults indulged in “a kind of exercise much like that which boys call Bandy in English.” Bandy is an old form of field hockey played on ice. The object of the game, Strachey says, was to drive a ball “between two trees appointed for their goal” by hitting it with a stick. Powhatan variants on the stickball game included a kick-the-ball version played mostly by women and boys, or drop-kicking the ball—essentially dropping it on the top of the foot the way a punter in modern American football does—and seeing who could kick it the farthest.

Information about Powhatan ball games, specifically stickball, is otherwise scant. But there is little doubt from descriptions emanating from other tribal records east of the Mississippi that the ancestor of modern lacrosse—the name derives from the French word for the stick—was widespread, testimony to the intimate trade contact over large distances between native peoples of the Americas. Language reinforces the perception of the game’s universal popularity. For example, we know that the Indians along the Mississippi called it pa-ki-ta, those of the upper Great Plains pe-ki-twe, farther north in Manitoba it was pa-ka-ha-to—all variants of the verb “to hit.”

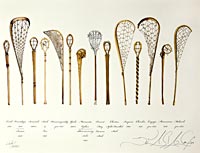

Rackets and balls acquired from Powhatan-allied tribes are housed in museums along the Atlantic seaboard. The idea of using a racket may have descended from the throwing stick, or atl-atl, sort of an arm extender used to add force and distance to a spear being hurled, as in modern jai alai. What started as the straightest stick, with a curved end, that could be hacked out in the forest developed into a two to four foot−long netted stick of woven bark or rawhide string.

What would evolve into the rackets we know today is an innovation of eastern woodland people. The similarity between the curved stick and the war club leads me to wonder whether idle warriors might have used the business ends of their cudgels to volley a random stone back and forth—the way we playfully kicked an intervening can down the road on the way to school when we were kids. The stringed pockets varied in size and shape, as did the length of the racket, the longest, Iroquoian, in the North being up to five feet and the shortest in the area of the upper Mississippi, two to three. A version of the game popular in the Southeast utilized two rackets, each one to two feet long.

Balls generally ranged in size between a tennis ball and a softball, though lighter in weight, and were usually made, as Strachey and Clayton tell us, of hide filled with animal hair, usually deer. Some Indians used balls made of wood.

Level playing fields of modest length and boundary markers are a thing of the present. Originally, the lacrosse field lay on rough ground with opposing goal trees, or posts if vegetation was not convenient, as much as a mile apart. One game witnessed by a colonist tells of two villages engaging each other, hundreds of men on the field at once. The swiftest players usually would engage at the center of the field and the slower arranged themselves around the goal posts. The heavier players held the ground in between.

Once the sphere was tossed up, the player who caught it “immediately set out at full speed towards the opposite goal. If too closely pursued, he throws the ball in the direction of his own side, who takes up the race”—this from a description by a mid-nineteenth century witness. This account fits the present version of lacrosse, except that the old game was more violent. Often in striking the opponent’s stick to dislodge the ball, a player inflicted severe injury to an arm or leg. One chronicler tells us: “Legs and arms are broken, and it has even happened that a player has been killed. It is quite common to see someone crippled for the rest of his life who would not have had this misfortune but for his own obstinacy.” In this instance the player refused to give up the ball, which he had trapped on the ground between his feet.

Why are contact sports so prone to violence? In the case of Native American lacrosse, violence may have been promoted at least in part by the extensive wagering that accompanied the game. For example, a Jesuit priest tells us the Huron would keep raising the stakes “till they had stript themselves stark naked and lost all their moveables in their cabins.” Some would not hesitate to wager their wives, children, and themselves into servitude.

Though a seeming vice, gambling in these cultures was a social leveler. When people wagered, they aided in the redistribution of material wealth. As in modern sports, over the years parity of talent and skill ensured stability between the tribes. So if you lost your goods on one contest, you stood a decent chance of recouping your losses later. Besides, if you lost a prized garment or weapon, you could always replace it. The more gambling thrived, the lower the odds that anyone would accumulate too much personal property, so long as the game was played frequently.

Like our athletes, the best lacrosse players trained exhaustively and intensely to keep in top shape. But unlike our athletes, they did it in strict isolation. They spent whole days in summer training, running, tumbling, and ball tossing from sun up to sundown to get ready for the customary fall season. To purify themselves, the sequestered warriors followed a special diet which excluded rabbit, a timid animal; frog, because his bones are brittle; and certain kinds of fish that move sluggishly, lest he acquire habits of these animals inimical to the game. Other taboos included consorting with women.

Shamans accompanied the players during training, making incantations to thwart the opponent a player feared the most. In one Cherokee training ritual, a shaman scratched the player’s body with a short comb made of sharpened splinters from the leg bone of a turkey. He plunged the teeth of the comb into the flesh at the shoulder and dragged it with constant pressure down the outside of the arm to the elbow. He repeated this action at a second spot on the shoulder, then a third, until the wound terminated at the now-bloody elbow—twenty-eight times. The player stood without flinching, enduring the torture, for he knew his stoic behavior during such an ordeal would ensure victory.

From the point of view of the modern contestant, participating in sport builds strength and character. One learns what it means to be a team player and to work with others. For today’s spectator, sports equal entertainment. We await our seasonal fling with basketball’s March madness, summertime baseball, college football on autumn Saturdays, and the NFL on Sundays. Though we can get caught up in wagering and in the violent aspects of the sport, in our world sports do not mirror life so much as they constitute an escape from it. Not so with the Indian.

Lacrosse was a way to settle arguments, a diplomatic tool. By agreement a contest allowed tribes to resolve territorial disputes. Ritualized battles reinforced political fellowship. When you have to hunt and gather, you can’t waste valuable time in constant warfare. This is why Indian confederacies arranged to contest one another at convenient times in the seasonal calendar. Games might be played on seasonal agrarian festivals or on the occasion of a celestial happening.

Lacrosse was also a mechanism for socialization. It promoted stability in the community by appealing to tradition. Every tribe had its own mythology about the first ball game that was played by the gods of creation. The ball that players volleyed back and forth over the land imitated the sun and the moon that moved back and forth across the sky back in the days when the gods played the game. And so, the players participated in reinforcing the cyclic conception of time common in indigenous America.

Further, lacrosse in native culture differed from the modern version in the way it went about reinforcing communalism in sports. The way Indians played the game, there was little specialization. There were no defensemen versus attackers, and there were few rules. Basically, anybody could do anything. As one might expect, on-the-field fights common in many of our team sports were rampant in the native version of stickball. Though seemingly counterproductive to the purpose of the game—it is all about winning, isn’t it?—these fisticuffs functioned as a way of toughening a man; they were a part of the individual rite of passage into manhood.

How did colonists become interested in the game of lacrosse? Two opposing things. In the summer of 1763, during the Seven Years’ War between Britain and France, the Fox played the Ojibwa in a game at Fort Michilimackinac, in what would become Michigan, to honor the birthday of King George III. The soldiers who witnessed the contest were fascinated by the rough play and the speedy back-and-forth engagement. Captivated, they began to wager with one another and root for their favorites, just like the Indian spectators. So focused on play were the troops that they were not aware that Indian women had been sneaking weapons into the fort and up toward the ring of spectators. All of a sudden, the Indians dropped their sticks, grabbed their weapons, and massacred the foreign onlookers.

In addition to being transfixed by witnessing a game in which they could have a personal stake, whites were impressed with the concept of the Indian athlete as the “noble savage.” This product of the Enlightenment survived into modern times, as white athletes idolized the Native American warrior of antiquity for his bravery, endurance, and purity in nature. Vestiges of the romanticized version of the Indian survive today in sports team names like the Redskins, the Warriors, and the Seminoles.

Thus lacrosse gained popularity among the “gentleman’s class” in Ontario, Canada, in the mid-nineteenth century. The game was quickly exported across the border into western New York State, then into the urban areas of New York, Philadelphia, and especially Baltimore and Annapolis. Advent of the synthetic stick and conversion of the field to a hockey-like box by Montreal hockey fans in the 1930s made lacrosse even more popular among whites, though it caused the game to diminish among descendants of the natives. Nonetheless, enthusiasts of the genuine article who live in the region where the Powhatan once drove the hair ball betwixt the trees can still find two-stick lacrosse being played in the Carolinas and Mississippi. Some college teams recruit skilled native stickmen. Sporadically disappearing and reappearing, today the old native game enjoys a record following. Organized professional leagues have surfaced during the past two decades, and college intramural and varsity lacrosse, which have long thrived in the northeast, are established at state universities across the South and West. The 2008 three-day NCAA Division I tournament in Philadelphia drew 125,000 fans.

Social leveler, spiritual connector, creative channeler of aggression, the gift of lacrosse from those who preceded the colonists in this land offers us one of team sports’ most important life lessons, whether we play it, witness it, or just read about it. As one Mohawk elder wrote, “Our grandfather told us that lacrosse was played for the enjoyment of the Great Spirit; everyone was important, no matter how big or small, or how strong or how weak.”

Anthony Aveni is the Russell Colgate Distinguished University Professor of Astronomy, Anthropology, and Native American Studies at Colgate University. His most recent books include People and the Sky: Our Ancestors and the Cosmos and Foundations of New World Cultural Astronomy.